As a smart hydration specialist, I often meet people who invested in a reverse osmosis system expecting “set it and forget it” performance, only to see their RO membrane fail in a year or two. The reality, confirmed by manufacturers, labs, and long‑term field data, is that most RO membranes fail early for preventable reasons.

Technical guidance from EAI Water, SoftPro Water Systems, and Membrane Solutions converges on a similar range: a well‑run residential or light commercial RO membrane usually lasts about 2–5 years, while the overall system can perform for 10–15 years or more when maintained carefully. In industrial plants, EAI Water reports entire RO trains running 15–20+ years. When membranes die in 6–12 months, it is almost always due to a specific failure mechanism, not “bad luck.”

This article walks through three practical decision questions:

- Is your RO membrane truly failing, or is it just dirty or stressed?

- What is most likely causing that failure in your specific water conditions?

- Which prevention steps give you the biggest return in membrane life and water quality?

Along the way, I will connect these questions to evidence from technical providers such as Axeon, Kurita America, AquaComponents, Vipanan Lab, and others, and I will keep the focus on steps a homeowner or facility operator can actually implement.

Question One: Is My RO Membrane Actually Failing?

Before you blame the membrane, it helps to distinguish between normal fouling that can be cleaned and irreversible damage that demands replacement.

What “failure” really looks like

Across sources like Axeon, Rotec, and Membrane Solutions, the same patterns appear when a membrane is in trouble:

You see noticeably weaker flow at the RO faucet or lower permeate production on an industrial panel, even though feed pressure has not changed much. You notice a decline in water quality: taste is off, TDS (total dissolved solids) is higher than usual, or the water looks cloudy. Rotec notes that an increasing wastewater‑to‑product ratio is another warning sign: more water is going to drain for the same amount of drinking water. You may also see energy use creeping up as pumps work harder to push water through fouled elements.

On the other hand, persistent loss of permeability that does not recover even after aggressive chemical cleaning strongly suggests irreversible damage. Membrane Chemicals points out that when you clean thoroughly and flux does not come back, root causes often include oxidation, solvent damage, or irreversible fouling that has collapsed or blocked the active layer.

A simple way to check membrane rejection

One of the most practical diagnostic tools you can use at home or in a plant is a handheld TDS meter. US Water Systems describes rejection like this: the membrane’s job is to remove a percentage of dissolved solids from the feed. If your tap water has 100 ppm TDS and the membrane rejects 90 percent of it, your purified water should have about 10 ppm.

You can calculate approximate rejection with a quick ratio:

Rejection (%) ≈ [(Feed TDS − Permeate TDS) ÷ Feed TDS] × 100

US Water Systems and Axeon both suggest that when rejection falls below roughly 80–85 percent, it is time to plan for membrane replacement, especially if cleaning does not restore performance. If you see rejection fall from 95 percent down to 82 percent and stay there after cleaning, you are looking at a membrane that is more than just dirty.

When cleaning is enough, and when replacement is smarter

Field guidance from Axeon and Kurita America recommends starting with cleaning if:

You are still within the normal 2–5‑year life window for that membrane. You see a gradual decline in flow and a gradual increase in differential pressure, typical of fouling or scaling. Your water quality is still acceptable, or only slightly worse.

In this scenario, you use cleaning‑in‑place (CIP) tailored to the foulant type. Acid formulations target carbonate and sulfate scale, while alkaline cleaners target biological and organic fouling. AquaComponents and Kurita both emphasize the importance of cleaning early, when flow has dropped by about 10–15 percent or when differential pressure increases by roughly 1 bar (about 15 psi) compared with the baseline.

Replacement is the better call when:

Cleaning no longer restores flux or rejection, as Membrane Chemicals warns. You see sharp, sudden changes such as a big jump in permeate conductivity combined with a surge in flux, which is a classic pattern of chemical attack. There is visible damage: element telescoping, torn leaves, crushed spacers, or compromised end caps, all observed repeatedly in the autopsy work summarized by Vipanan Lab.

In my own field work, I treat membranes as cleanable “assets” for as long as they respond predictably to cleaning. Once they stop responding, treating them as consumables and replacing them is usually cheaper than repeatedly fighting an already‑damaged surface.

Question Two: What Is Causing My Membrane Problems?

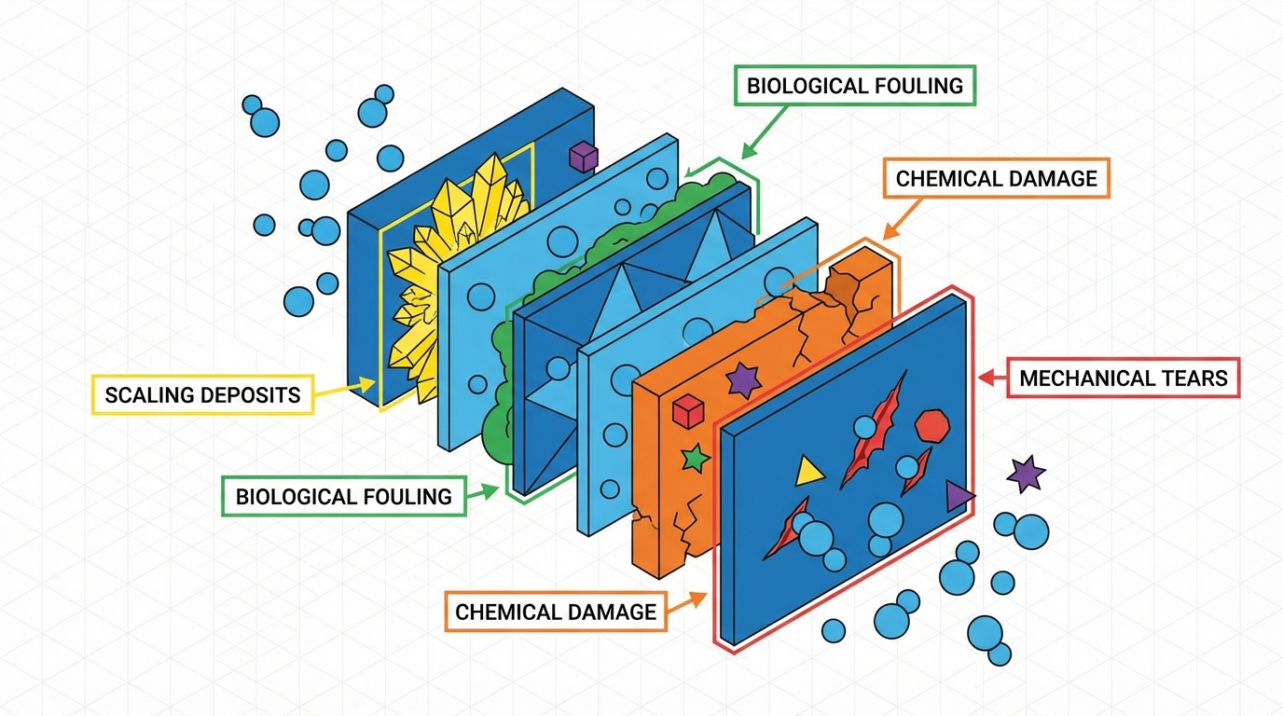

Almost every “mystery failure” I see falls into four technical buckets: scaling, fouling, chemical attack, and mechanical or operational stress. The research notes line up well with this picture: AquaComponents, Hydrocell, J.Mark Systems, Kurita America, Viomi, and Vipanan all describe the same set of root causes.

To orient you, here is a quick overview before we go deeper.

Primary cause |

Typical clues in the real world |

Key prevention levers |

Mineral scaling |

Gradual flow loss, rising pressure drop, chalky or crystalline deposits, especially with hard or high‑TDS water |

Antiscalants, softening or hardness control, conservative recovery, good pretreatment |

Particulate/organic/bio‑fouling |

Rapid or stepwise flow loss, rising pressure drop, slimy or dirty deposits, high SDI or turbidity in feed |

Sediment and media filtration, MF/UF, regular cleaning, controlled disinfection with dechlorination |

Chemical oxidation/attack |

Sudden jump in permeate conductivity, unexpected increase in permeability, discoloration or deformation of elements |

Reliable dechlorination, pH control, compatible cleaners, non‑oxidizing biocides |

Mechanical/operational stress |

Tears, telescoping, crushed spacers, persistent high differential pressure, short membrane life in high‑pressure systems |

Staying within design pressure, avoiding pressure shocks, correct staging and recovery, compatible pre‑treat |

Scaling: When minerals turn into rock inside your membrane

Scaling is the slow crystallization of dissolved minerals onto the membrane surface. AquaComponents describes this as the concentration of salts such as calcium carbonate, calcium sulfate, silica, and barium or strontium sulfate beyond their solubility limit, so they precipitate and clog membrane pores.

In practice, you are at greatest risk if:

Your water is hard or has high TDS. Mountain Fresh Water and SoftPro Water Systems both highlight hard water as the dominant enemy of RO membranes. SoftPro cites data showing that hard water can cut membrane life by about 30 percent, and that homes with TDS above 500 ppm often see lifespans of just 2–3 years without additional treatment. Recovery is pushed too high. AquaComponents notes that increasing recovery concentrates minerals in the remaining brine, driving scaling. They cite typical brackish water recovery ranges of about 45–75 percent; pushing past the design range without adjusting pretreatment is risky. Temperature creeps up and silica is high. AquaComponents points out that silica scale forms a glass‑like film at elevated temperatures, which is extremely hard to remove.

The symptoms build slowly: permeate flow falls, pressure drop increases across the array, energy use rises, and water quality declines as areas of the membrane are blocked. At autopsy, scaling shows up as hard white or glassy deposits.

A real‑world example from EAI Water illustrates the payoff of good hardness control. In one industrial facility, adding pre‑treatment to remove hardness minerals reduced membrane fouling by 50 percent and extended membrane life significantly, lowering maintenance cost. That is exactly what we see in many home installations too: adding a softener or antiscalant upstream often doubles membrane life in hard‑water regions.

Prevention relies on three main levers that AquaComponents, Hydrocell, and Kurita America all emphasize. First, control hardness and other scale‑forming ions before they reach the membrane using softening, media filtration to remove iron and manganese, or nanofiltration in difficult brackish waters. Second, dose antiscalants tuned to your water chemistry; these chemicals interfere with crystal nucleation and growth so minerals stay in solution instead of plating the membrane. Third, run the system within a conservative recovery range, especially if your feed water has high hardness or silica.

Monitoring tools such as Langelier Saturation Index (for calcium carbonate) and Silt Density Index (for particulate load) help you predict scaling and adjust antiscalant dosage or recovery before damage occurs, as described by AquaComponents and Axeon.

Fouling: Sediment, organics, and biofilm choking the membrane

While scaling is primarily mineral, fouling is mostly about particles, organics, and living organisms. Axeon defines membrane fouling as the accumulation of particulate, organic, or biological material on the membrane surface, which shows up as reduced permeate flow, increased differential pressure, higher energy use, and poorer water quality.

J.Mark Systems and Kurita America break fouling into several categories:

Particulate or colloidal fouling arises from silt, dust, clay, and fine suspended solids. Biofouling happens when bacteria, algae, or fungi colonize the membrane and form slimy biofilms. Organic fouling comes from natural organic matter, oils, greases, and humic substances that adsorb into the membrane. Iron and metal fouling occurs when iron or manganese oxidize and precipitate on the surface.

Axeon notes that an SDI (Silt Density Index) above about 5 for tap‑water applications indicates high fouling risk, and Kurita recommends evaluating turbidity and SDI routinely to understand the particulate load hitting your RO system.

A powerful example of the value of good pretreatment comes from a peer‑reviewed review summarized in the PMC literature notes: ultrafiltration used as a pretreatment stage was able to reduce SDI to below about 2.5 and remove 98–99.5 percent of turbidity, dramatically improving downstream RO performance. Compared with conventional pretreatment alone, membrane‑based pretreatment removed roughly 90 percent of biofilm‑forming bacteria instead of about 30 percent. That difference directly translates into less biofouling and longer cleaning intervals.

Practically, fouling control comes down to the quality of your pretreatment train and the discipline of your maintenance routine. Sediment prefilters and media filters remove larger particles before they reach the RO element. Activated carbon protects both against chlorine (for chemical safety) and some dissolved organics. In more demanding applications, microfiltration or ultrafiltration ahead of RO can be transformational. The PMC review and Kurita America both highlight combinations such as coagulation–flocculation, dissolved air flotation, and media filtration followed by UF and then RO as very effective for difficult surface waters.

For home and light commercial systems, a simpler version of that philosophy still applies. ESP Water and EAI Water recommend changing sediment and carbon prefilters every 6–12 months, or sooner if you see a noticeable pressure drop. If you let those inexpensive filters clog, silt and organics bypass them and foul your far more expensive RO membrane.

Chemical attack and oxidation: Invisible but often permanent

Modern RO membranes are typically polyamide thin‑film composites. Hydrocell, Axeon, and NEWater all stress that this polyamide layer is highly sensitive to oxidizing agents such as free chlorine, chloramines, ozone, chlorine dioxide, permanganate, and even hydrogen peroxide under certain conditions.

When oxidants reach the membrane, several things happen. The polymer chains in the active layer are attacked and broken (halogenation or oxidation), which increases permeability but reduces selectivity. Membrane Chemicals describes a characteristic pattern: a sharp increase in permeability combined with higher permeate conductivity, often caused by halogenation from chlorine or oxidation from agents such as permanganate or chlorine dioxide. Even oxidants that are sometimes considered “compatible,” like hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid, can cause localized damage in the presence of metal ions such as iron or manganese.

NEWater explains that trace residual chlorine, together with heavy metal ions like copper, iron, and aluminum, can catalyze oxidation reactions, accelerating degradation of the desalination layer. The operational result is a decline in salt rejection, altered flux, and a shortened membrane life.

You will not see oxidant damage as quickly as a broken pipe, but the implications for water quality are serious. Membrane Chemicals notes that poor salt rejection from damaged membranes raises the risk of contaminants like arsenic, nitrate, boron, or PFAS breaking through, and it increases the loading on downstream polishing steps such as ion exchange resins.

Prevention centers on never allowing oxidants to reach the RO inlet. Carbon filtration and sodium bisulfite dosing are the standard tools to remove chlorine and other oxidants upstream. NEWater recommends installing online oxidation–reduction potential or residual‑chlorine meters to ensure that oxidant levels are effectively zero at the RO feed. For disinfection of RO systems, they advocate using non‑oxidizing biocides such as DBNPA or isothiazolinones rather than chlorine.

Mechanical and operational stress: Pushing membranes beyond their limits

The final failure mode is less glamorous but just as real: mechanical damage and operational abuse.

Vipanan Lab, Chunkero Water Plant, and Viomi all describe cases where membranes were simply operated outside their design window. Excessive operating pressure can tear or rupture the membrane leaves. Chunkero notes that running seawater systems above maximum design pressure leads to tears and compromised system stability. Mechanical shocks from rapid pressure changes can telescope elements or migrate feed spacers, which Membrane Chemicals associates with increased differential pressure and abrasion of the active surface.

pH extremes are another subtle but important stress. Vipanan highlights pH imbalance as a contributor to membrane deterioration, while SoftPro Water Systems notes that RO performance is optimal when feed pH is roughly in the 6–8 range; both low pH (acid attack) and high pH (scale formation, especially in hard water) shorten life.

Changing feedwater sources can also be a kind of “operational stress.” Viomi points out that switching between chlorinated municipal water, hard well water, and turbid surface water exposes membranes to shifting chemistry that increases the risk of scaling, fouling, chemical attack, and pressure swings. If your pretreatment is only designed for the easiest source, the membrane sees unplanned spikes of hardness, iron, chlorine, or turbidity when the source changes.

In autopsy case studies collected by Vipanan, hidden causes such as incompatible prefilters, mismatched membrane materials, and unmonitored rejection rates show up repeatedly. Many failures were not the result of a single dramatic event, but of months or years of running with slightly wrong chemistry or operating conditions, slowly grinding down the membrane until it finally crossed a failure threshold.

Question Three: How Do I Prevent Premature RO Membrane Failure?

Once you understand the four main failure modes, prevention becomes a question of designing the right protection for your water and then maintaining it with discipline. Here is how I guide homeowners and facility operators, tying back to what the evidence shows.

Step one: Know your water and set realistic membrane life expectations

SoftPro Water Systems and Membrane Solutions both emphasize that membrane life is dominated by feedwater quality. In residential systems, a 2–3‑year membrane life is common with hard or high‑TDS water, whereas 4–5+ years is realistic in low‑TDS regions when pretreatment is robust. SoftPro notes Water Quality Association data showing that high‑TDS homes above about 500 ppm typically see 2–3‑year lifespans, while homes under about 100 ppm TDS often reach 4–5 years or more.

Before you optimize anything else, have your water tested. At a minimum, know TDS, hardness, iron and manganese, pH, and whether any oxidizing disinfectant (like chlorine or chloramine) is present. For facilities, EAI Water recommends a comprehensive analysis program with regular lab testing to guide pretreatment design.

Once you know your water, you can decide: Is a 2–3‑year membrane life acceptable? If not, you will need additional pretreatment, and the evidence shows that investment typically pays back in reduced fouling and longer life. EAI Water describes a case where adding hardness removal cut fouling by 50 percent and significantly extended membrane life.

Step two: Build a pretreatment train that protects the membrane, not just meets minimum specs

Across AquaComponents, Kurita America, PMC literature, J.Mark Systems, and Viomi, one message is consistent: robust pretreatment is the single best investment you can make in membrane health.

For a typical home or small commercial RO unit, that means, at minimum, a sediment prefilter to catch dirt, silt, and rust, plus one or more carbon filters to remove chlorine and some organics. ESP Water and EAI Water both recommend replacing these prefilters every 6–12 months or whenever you observe a noticeable pressure drop; delaying replacement allows sediment and chlorine to reach and foul or damage the membrane. The RO membrane itself can then last around two years or more when prefilters are maintained, as ESP Water notes.

In tougher conditions, you may need to go further. AquaComponents recommends softening or antiscalant dosing to deal with hardness and barium or strontium sulfates. J.Mark Systems and Kurita highlight coagulation and multi‑media filtration to remove suspended solids, followed by microfiltration or ultrafiltration to substantially reduce turbidity, SDI, and biofouling risk. The PMC review reports that ultrafiltration pretreatment lowered SDI to below about 2.5 and removed 98–99.5 percent of turbidity in tested waters, which is a very strong foundation for downstream RO.

Viomi adds that, for variable sources, pretreatment should be designed for the worst‑case conditions of each source. If your system may see both hard iron‑bearing well water and chlorinated city water, pretreatment must be able to handle both hardness and oxidants so that the membrane never experiences spikes of either.

Step three: Control oxidants, pH, and recovery before they control you

SoftPro Water Systems, Hydrocell, Axeon, and NEWater collectively underline three operating parameters that make or break membrane life: oxidant exposure, pH, and recovery.

Oxidants should never reach the RO membrane. That requires dependable carbon filtration and, for many larger systems, sodium bisulfite dosing to neutralize residual chlorine. NEWater recommends online ORP or residual‑chlorine monitoring and regular offline testing, particularly for systems that use upstream chlorination for bio‑control. This is not just a matter of protecting the membrane polymer; Membrane Chemicals warns that oxidant‑damaged membranes lose salt rejection and can allow regulated contaminants through.

pH should stay within the membrane manufacturer’s recommended range, typically around 6–8 for many thin‑film composites according to SoftPro. High pH in a hard‑water system encourages carbonate scaling, while low pH can chemically attack membrane materials and support structures. Vipanan’s autopsy work shows pH imbalance as a recurring factor in premature degradation.

Recovery, or the fraction of feed converted into product, should be chosen conservatively for your water quality. AquaComponents suggests about 45–75 percent recovery for brackish water and 35–50 percent for seawater systems. Running at the high end of these ranges with high hardness or silica is almost guaranteed to increase scaling risk, especially if you do not adjust antiscalant dosage or softening accordingly. In my practice, I would rather see a slightly lower recovery with stable performance than “squeeze” a few percent more product and pay for it in frequent cleanings and early replacement.

Step four: Monitor performance and act at the first signs of trouble

Multiple sources emphasize that monitoring and recordkeeping are not “nice‑to‑haves”; they are core to membrane health. Axeon recommends maintaining detailed operating logs, and EAI Water describes a dairy facility that introduced weekly inspections and monthly performance assessments, cutting unexpected repairs and adding about five years to the system’s operational life.

At a minimum, track:

Feed pressure, permeate pressure, and differential pressure across the membrane stages. Permeate flow and, if possible, normalized permeate flow that accounts for temperature changes. Feed and permeate TDS to estimate rejection. Cleaning dates and chemicals used.

Kurita and Viomi recommend triggering cleaning when normalized permeate flow drops by around 10–15 percent, differential pressure increases by roughly 1 bar (about 15 psi), or salt rejection falls to around 90 percent compared with new conditions. AquaComponents and Axeon both stress that cleaning early, while fouling and scaling are still reversible, is far more effective than waiting until performance has collapsed.

For homeowners, that can be as simple as checking TDS once a month at the kitchen faucet and noting how long it takes to fill a known container. If TDS has crept up significantly and filling time has doubled compared with when the membrane was new, you have useful data to decide whether cleaning or replacement is necessary.

Step five: Use autopsies and expert diagnostics for chronic or high‑value systems

When a system continues to struggle despite good pretreatment and regular cleaning, or when the stakes are high (for example, a pharmaceutical or beverage facility), it is worth going beyond surface symptoms.

Vipanan Lab and Membrane Chemicals both advocate membrane autopsy as the most definitive way to understand what actually went wrong. Membrane Chemicals describes performing up to about 25 analytical tests per autopsy, looking at fouling type, degree of oxidation, mechanical damage, and even the presence of incompatible polymers or surfactants. Vipanan recommends scheduling autopsy analysis when salt rejection drops by more than about 10 percent or when differential pressure spikes sharply and does not respond to normal cleaning.

The goal is not just to “prove” that a membrane failed, but to close the feedback loop: use what you learn to refine pretreatment, adjust chemical dosing, and correct operating conditions so that the next membrane lives longer. In my experience, one good autopsy can pay for itself many times over by preventing repeated, unexplained failures.

A Quick Example: How These Steps Change Real‑World Lifespan

It is helpful to connect the science back to lifespan in everyday terms.

SoftPro Water Systems reports that in hard‑water homes with TDS above about 500 ppm, membranes often last only 2–3 years without extra protection. In contrast, homes with low TDS below roughly 100 ppm can see 4–5+ years from the same membrane model when pretreatment and maintenance are strong. EAI Water shares a case where adding hardness removal reduced fouling by 50 percent, while another facility that instituted weekly inspections and monthly performance checks extended system life by about five years. EAI also notes a plant that extended membrane life by about 18 months simply by implementing a regular cleaning schedule based on performance indicators instead of waiting for visible problems.

These numbers are consistent with what I see in the field: when people combine proper pretreatment, conservative operating conditions, and proactive monitoring, membranes routinely hit the upper end of the 2–5‑year window cited by Membrane Solutions, Rotec, Axeon, and others. When they do not, early scaling, fouling, oxidant exposure, or pressure abuse almost always explains why.

Short FAQ: Everyday Decisions About RO Membrane Health

Q: How often should I replace my RO membrane if everything looks fine? Most sources, including Membrane Solutions, SoftPro, US Water Systems, and EAI Water, converge on about 2–5 years for residential and light commercial membranes, with 2–3 years common in hard‑water or high‑TDS conditions and up to 4–5 years in gentler water with strong pretreatment. Even if performance still seems acceptable, replacing within that window reduces the risk of silent degradation and sudden failure.

Q: Do I really need both a softener and an antiscalant for hard water? Hardness control is non‑negotiable if your water is very hard. Data summarized by SoftPro and Mountain Fresh Water show that hard water shortens membrane life significantly. EAI Water’s case study shows that removing hardness cut fouling by about 50 percent. Whether you use a softener, antiscalant, or both depends on your design and space constraints. In smaller residential systems, a softener plus standard prefilters is often enough. In higher‑recovery or industrial systems, a softener or hardness‑removal step plus a well‑chosen antiscalant, as described by AquaComponents and Hydrocell, offers more robust protection.

Q: When should I consider sending a membrane for autopsy instead of just swapping it out? Autopsy is most valuable when the cause of failure is unclear or when the system is critical. Vipanan and Membrane Chemicals suggest considering autopsy when salt rejection has dropped more than about 10 percent from baseline, differential pressure has risen sharply and stays high after normal cleaning, or when membranes are failing much earlier than their expected 2–5‑year life even with reasonable pretreatment. In those cases, understanding the exact mix of fouling, scaling, chemical attack, or mechanical damage is the key to breaking the cycle of repeat failures.

In the end, RO membrane health is not a mystery; it is the predictable outcome of your water chemistry, system design, and day‑to‑day operating choices. When you combine good pretreatment, gentle but effective operating conditions, and data‑driven maintenance, you not only protect a high‑value component, you also protect the quality of every glass of water in your home or facility. That is the heart of smart hydration: water that is not just clean on paper, but consistently safe, reliable, and reassuring to drink.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10102236/

- https://www.membrane-solutions.com/blog-How-Often-Should-RO-Membrane-Be-Replaced

- https://www.chunkerowaterplant.com/news/reverse-osmosis-water-filter-membrane

- https://eaiwater.com/how-long-does-a-reverse-osmosis-system-last/

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/reverse-osmosis-maintenance

- https://www.jmarksystems.com/blog/u105ptfbi7o6zvvetx9tbpsxxr09yv

- https://www.kuritaamerica.com/the-splash/membrane-fouling-common-causes-types-and-remediation

- https://mfwater.com/the-impact-of-hard-water-on-reverse-osmosis-systems/

- https://www.newater.com/prevent-oxidation-of-reverse-osmosis-membrane/

- https://pearlwater.in/blog/common-problems-with-ro-membranes-and-how-to-solve-them?srsltid=AfmBOoqej_AyBlnQOR7juVbZiHdpgWGtwPPjs0dULylAxk73F-av-P7S

Share:

Understanding Why Your RO System Sometimes Refuses to Operate

Understanding Why Your Pump Starts But Lacks Pressure