As a Smart Hydration Specialist and water wellness advocate, I meet a lot of homeowners who are stuck between two frustrations: white crust on every fixture from hard water, and growing concern about invisible contaminants like PFAS and lead. Reverse osmosis (RO) looks like the obvious answer, but there is a real question hiding underneath: is an RO system actually a good idea when your water is very hard?

The short answer is that RO can work extremely well in hard-water areas and can dramatically improve water safety and taste, but only when you treat hardness seriously in the design. In some homes, RO is a great fit with minimal extra work; in others, it is not the first tool I recommend. The difference comes down to hardness level, overall water chemistry, system type, and how much maintenance and water waste you are willing to manage.

In this article, I will walk you through the science and the practical decision points, drawing on both field experience and research from sources such as the US EPA, Duke University, and peer‑reviewed health studies.

What “High Hardness” Really Means

Hard water is water rich in dissolved calcium and magnesium. As groundwater moves through mineral‑rich rock, it picks up these ions, which then show up in your home as scale, soap scum, and cloudy glassware. Several technical sources define hardness categories such as soft, moderately hard, hard, and very hard based on concentration of these minerals, usually reported as calcium carbonate.

Support teams that work with home RO systems commonly see city water in the roughly three to eight grain per gallon range and well water commonly in the seven to twenty grain per gallon range. That means many private wells sit solidly in the “hard” to “very hard” category.

From a hydration and health perspective, hardness minerals are not usually harmful and can even contribute a small amount of calcium and magnesium. The real issues are practical. Hard water:

Clogs showerheads, faucets, and small appliance lines with limescale. Coats water heater elements and tank interiors, raising energy use and shortening equipment life. Leaves white spotting on dishes and glassware and stubborn soap scum on showers and sinks. Makes skin and hair feel dry or dull because soap does not rinse cleanly and minerals interfere with natural oils.

These effects are documented across multiple consumer and technical guides on water softening and RO and are exactly what I see in homes across high‑hardness regions.

How Reverse Osmosis Works – And Why Hard Water Is a Challenge

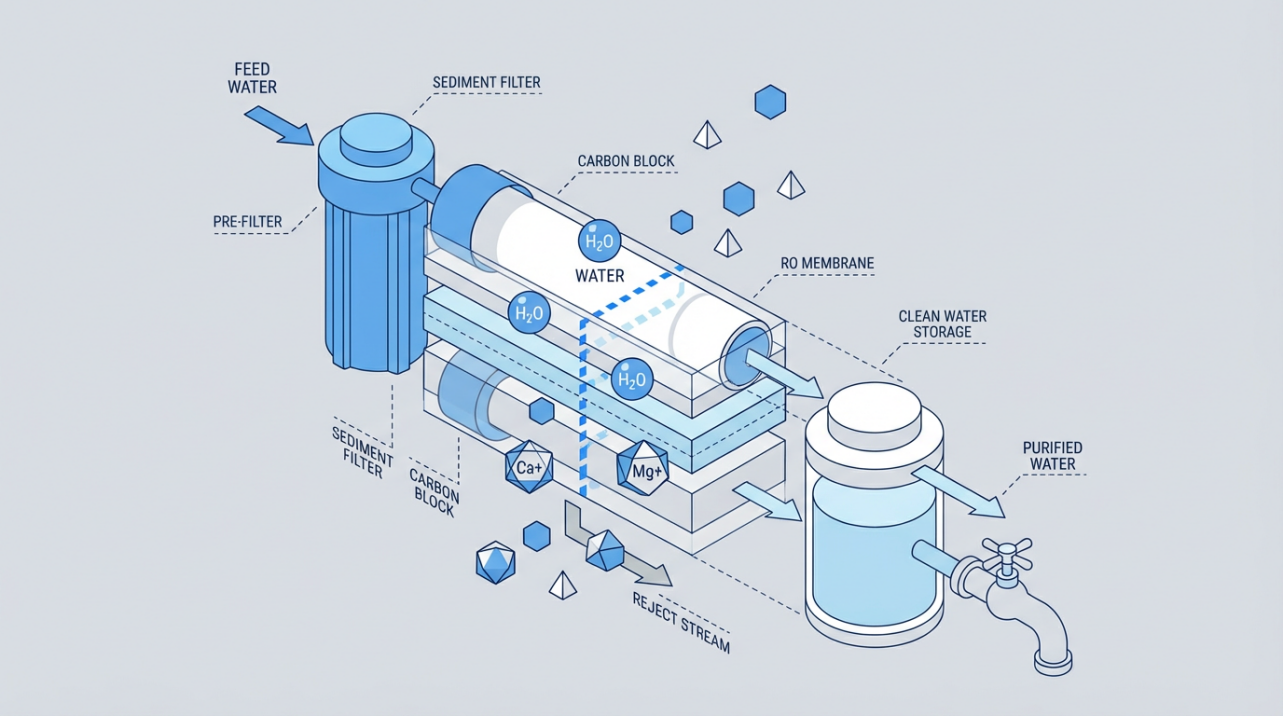

Reverse osmosis is a high‑performance filtration process. Pressure pushes water through a semi‑permeable membrane that is fine enough to reject most dissolved solids and many microscopic contaminants. Residential RO systems are typically multi‑stage. A common layout includes a sediment pre‑filter to catch dirt and rust, a carbon pre‑filter to remove chlorine and volatile organic compounds, the RO membrane itself, and a post‑carbon “polishing” filter to refine taste and odor.

Well‑designed RO systems can remove up to about 99 percent of dissolved minerals and contaminants. Studies and product testing show strong reduction of heavy metals, salts, fluoride, arsenic, microplastics, pesticides, and even many bacteria and viruses. A 2020 study from Duke University found that under‑sink RO and some two‑stage systems achieved at least 94 percent reduction of PFAS, those so‑called “forever chemicals” that now show up in the blood of most Americans. This is why RO is considered one of the most effective consumer technologies for dealing with PFAS, lead, and similar contaminants.

From a water‑wellness point of view, this is a major strength in both city and well water. Many municipal systems still struggle with lead at the tap, especially in older neighborhoods, and regulatory violations under the Safe Drinking Water Act are not rare. Private well owners are on their own for treatment and commonly face a mix of hardness, iron, manganese, and high total dissolved solids. In these settings, RO can move you from “technically compliant but questionable” water to consistently clean, clear water at the faucet.

However, RO membranes and scale do not get along. Hardness minerals are one of the main reasons RO underperforms or fails in high‑hardness areas.

Where Hard Water Fights Back: Scaling And Efficiency Loss

When hard water feeds an RO system, calcium and magnesium tend to precipitate as scale on the membrane surface and in internal flow passages. Technical articles from Mountain Fresh Water, industrial water‑treatment providers, and others describe the same cascade of problems.

First, scaling physically clogs membrane pores and flow channels. When that happens, it takes more pressure to push water through, so the system’s energy use and wear go up. In residential systems without a pump, you feel it as lower production and a slow faucet.

Second, as scale builds, the membrane’s ability to reject contaminants declines. That means you may still get water out of the tap, but its total dissolved solids and contaminant levels rise compared with a clean membrane.

Third, chronic scaling shortens membrane life. Instead of getting a typical two to five years out of a residential membrane (assuming decent feed water and proper pre‑filtration), membranes exposed to very hard water may need replacement much sooner. Industrial and ZLD (zero liquid discharge) studies show the same pattern at larger scale: more hardness means more cleaning, more downtime, and more frequent membrane replacement.

Finally, high hardness pushes you to operate at lower recovery to avoid heavy scaling. Recovery is the fraction of feed water that ends up as purified permeate. Lower recovery means more concentrate (wastewater) per gallon of drinking water. Hard water therefore affects not just how often you change membranes but also how much water you send down the drain.

Support guidance from one RO manufacturer recommends keeping hardness below about seven grains per gallon to optimize membrane performance and lifespan.

Above that, the system can still run, but you should expect more frequent filter and membrane changes, and you should plan pretreatment instead of relying on the RO alone.

Feasibility Question 1: What Is Your Hardness Level?

Before deciding whether an RO system is feasible in your high‑hardness area, you need to know how hard your water actually is. The good news is that this is straightforward.

Municipal customers can start with their annual water quality report. These reports usually list hardness as calcium carbonate and often note whether the supply is considered soft, moderately hard, or hard. However, distribution pipes, local blending, and premise plumbing can change things between the plant and your kitchen sink. Several RO and softener manufacturers specifically recommend direct testing at the home.

For private wells, direct testing is essential. Articles aimed at well owners point out that well water hardness often falls in the higher ranges and may come bundled with iron, manganese, or high sulfate. The combination of scale‑forming minerals and other metals is especially hard on RO membranes.

In practice, that means you either use a test kit or strips designed for hardness or have a licensed water treatment professional run a more complete panel. Given how often I find lead, nitrates, and other contaminants in hard‑water wells, I strongly prefer full water testing rather than checking hardness alone. Several expert guides explicitly advise this step before choosing an RO system.

Once you know your hardness and broader water chemistry, you can assess feasibility more clearly:

If you are in the lower end of “moderately hard” water, a point‑of‑use RO system with good pre‑filtration may be feasible without softening, especially on city water. If you are solidly in the “hard” or “very hard” range, especially on a well, a softener or other hardness‑control strategy almost always needs to be part of the plan if you want an RO system to last.

Feasibility Question 2: What Type Of RO System Are You Considering?

Not all RO setups react the same way to hard water. Choosing the right format is part of making RO feasible.

Point‑of‑use under‑sink systems are the most common home RO installations. They sit under the kitchen sink and feed a dedicated drinking‑water faucet, sometimes also the refrigerator. They combine pre‑filters, the membrane, and a small storage tank. Because they treat only a few gallons per day, their overall scaling load is smaller than a whole‑house system. With properly managed hardness, many people in hard‑water areas run these successfully.

Countertop RO systems are a compelling option for renters and those who cannot modify plumbing. Modern designs are plug‑and‑play, often with integrated multi‑stage filtration and sometimes with remineralization cartridges. They treat water by the jug rather than continuously. Several brands include performance verification and contaminant testing, giving confidence in hardness and TDS reduction even without complex installation.

Whole‑house RO is a different animal. Here, RO is installed at the main water entry and supplies RO‑quality water to every tap. Technical guides aimed at contractors emphasize that this is larger, more expensive, and more complex to maintain. For a whole home, hardness management becomes even more critical because the RO unit sees large volumes and higher scaling risk. Whole‑house RO tends to be reserved for very specific needs, such as high‑TDS wells where hardness, sodium, and other contaminants are extreme.

Across all formats, one pattern is consistent in both residential and industrial literature: RO performs best on softened or otherwise hardness‑controlled feed water. That brings us to the most important design decision in a high‑hardness area.

The Role Of Water Softeners, Pretreatment, And Antiscalants

Water softeners and RO are often misunderstood as competing options, but they actually solve different problems and can be powerful partners.

A softener uses ion exchange resin to replace hardness ions like calcium and magnesium with sodium. That dramatically reduces scale throughout the plumbing system. However, softeners do not remove most harmful contaminants such as heavy metals, PFAS, pesticides, or microbes. RO, by contrast, is designed to remove those contaminants but is vulnerable to scale from hardness.

Multiple homeowner and manufacturer guides make the same core recommendation: in hard‑water regions, install the softener upstream of the RO system. This approach:

Protects the RO membrane from scale, extending membrane life. Improves RO efficiency and helps maintain higher recovery without severe scaling. Reduces the frequency and cost of RO filter and membrane changes. Addresses whole‑house hardness issues like soap scum and appliance wear that RO alone cannot fix, since RO is usually point‑of‑use.

Other pretreatment methods may also be appropriate depending on water chemistry. Industrial and municipal case studies illustrate some options:

Sediment and multimedia filters to remove particles that would otherwise act as scale nucleation sites. Iron and manganese removal, often with oxidizing steps and specialized media, because insoluble iron and manganese are notorious for fouling RO membranes. pH adjustment and dosing of antiscalant chemicals prior to the RO unit to inhibit mineral precipitation on membrane surfaces.

In an early municipal RO plant in Minnesota, engineers combined aeration, oxidation, greensand filtration, pH adjustment, and an anti‑scalant before water reached the membranes. That plant achieved about 75 percent recovery at the RO skid and over 80 percent overall efficiency, while producing water that was approximately 97 percent free of hardness, sulfate, sodium, and arsenic. The scale of that project is larger than a home, but the principle is identical: RO feasibility in hard water hinges on smart pretreatment.

For homes, the practical version of that complexity is usually a softener, a good sediment/carbon pre‑filter, and sometimes an antiscalant or iron filter for difficult wells.

Feasibility Question 3: Water Efficiency, Waste, And Hardness

RO does not only concentrate contaminants in its waste stream; it also concentrates hardness. The harder your feed water, the more scale‑forming minerals accumulate on the concentrate side of the membrane. To keep that from precipitating onto the membrane itself, you usually need to limit how far you push recovery.

That matters because residential RO systems already have a reputation for wasting water. A point‑of‑use RO unit typically sends several gallons of reject water down the drain for every gallon of purified water produced. The US EPA’s WaterSense program notes that many conventional under‑sink systems waste at least five gallons of reject water per gallon of treated water, and some inefficient models waste up to ten.

Recognizing this, the EPA created efficiency criteria for point‑of‑use RO. To earn the WaterSense label, an RO system must send no more than about 2.3 gallons of water down the drain for every gallon of treated water, while also meeting performance metrics such as minimum membrane life and baseline total dissolved solids reduction. The EPA estimates that replacing a typical under‑sink RO with a WaterSense‑labeled model can save more than 3,100 gallons of water per year, adding up to roughly 47,000 gallons over the lifetime of the system.

In high‑hardness areas, these efficiency questions are magnified. If you do not control hardness, you may need to run the system at lower recovery to keep scaling in check, which increases waste. If you soften upstream, you can usually operate closer to the system’s intended recovery without excessive scale, which improves efficiency.

A simplified way to think about it is summarized here:

System configuration |

Typical waste per gallon produced* |

Notes in high‑hardness water |

Older under‑sink RO, no softener |

Often 5–10 gallons |

Needs lower recovery to avoid scale; high waste |

Modern RO without efficiency label |

Around 3–4 gallons in many designs |

Performance depends heavily on hardness |

WaterSense‑labeled point‑of‑use RO |

2.3 gallons or less |

Requires good pretreatment to keep that ratio |

*Values based on ranges reported in residential RO and EPA WaterSense guidance.

If your region faces water scarcity or you are on a private well where every gallon counts, choosing a high‑efficiency, WaterSense‑labeled design and managing hardness becomes essential to make RO feasible.

Feasibility Question 4: Health And Taste Tradeoffs With Very Soft RO Water

In hard‑water areas, homeowners often assume that “the softer the better.” From a plumbing perspective that is mostly true. From a hydration perspective, there are a few nuances.

RO water is not just low in hardness; it is low in almost all dissolved minerals. Membrane manufacturers and clinical reviews report that RO often removes more than 90 to 98 percent of dissolved ions. One research review found typical reductions around 97 percent for calcium, 96 percent for magnesium, 95 percent for fluoride, and about 90 percent for nitrate. That produces very low‑mineral, soft water.

Several nutrition and dental sources emphasize that most of our mineral intake does come from food rather than drinking water. For example, a glass of tap water may only provide a few milligrams of calcium and magnesium, compared with hundreds of milligrams in common foods like yogurt or nuts. Consumer‑focused RO guides make this point to reassure homeowners that removing minerals from water is usually not a serious concern for healthy adults eating a balanced diet.

However, more detailed research adds an important layer, especially for children and long‑term health. Narrative reviews and epidemiological studies have linked chronic consumption of very low‑mineral water to:

Slightly higher rates of dental caries in children drinking low‑mineral water compared with those drinking water that contains moderate calcium, magnesium, and fluoride. Signs of dental hypoevolutism and growth issues in populations where low‑mineral, demineralized water was the primary drinking water through critical development periods. Changes in bone mineral density risk, due in part to lower dietary intake of calcium and magnesium from water and potential alterations in vitamin D metabolism. Altered mineral and water homeostasis, with increased diuresis and different patterns of electrolyte excretion.

The World Health Organization has also flagged long‑term exclusive use of demineralized water as a potential risk factor because it lacks beneficial trace elements.

This does not mean RO water is “dangerous” in high‑hardness areas; it is far safer than contaminated water with lead, PFAS, or pathogens. It does mean that we should treat remineralization as a best practice, not an afterthought, particularly for families with children.

The practical solutions are straightforward and well established:

Many modern under‑sink and countertop RO systems include a remineralization cartridge that adds back calcium, magnesium, or alkalizing minerals after the membrane. Testing of systems like AquaTru and app‑connected under‑sink models shows that these filters can raise pH, restore some mineral content, and improve taste, even while total dissolved solids remain much lower than tap water. If your RO system does not include remineralization, you can use inline mineral cartridges, alkaline pitchers, or trace‑mineral drops. Technical reviews list several options, from contact with calcium carbonate media under controlled conditions to the addition of specific mineral salts and alkaline media. Regular dental care, appropriate fluoride exposure, and a balanced diet rich in calcium, magnesium, and vitamin D remain critical, regardless of water source.

In a high‑hardness home, I like to frame this as a trade: you are removing an excess of scale‑forming minerals and a wide range of contaminants, then intentionally adding back a moderate, controlled mineral profile that supports both palatability and long‑term wellness.

Feasibility Question 5: Budget, Maintenance, And Lifecycle Costs In Hard Water

Any assessment of RO in a hard‑water area has to factor cost and maintenance. Here, the research is surprisingly encouraging, as long as you plan realistically.

Cost comparisons between RO and bottled water show large savings over time. One lifecycle analysis found that a standard countertop RO unit typically costs about 300 to 500 dollars upfront, with annual maintenance in the range of roughly 120 to 155 dollars for pre‑filters, carbon cartridges, optional remineralization filters, and periodic membrane replacement every two to three years. That works out to around 32 to 42 cents per day for essentially unlimited filtered drinking water.

In contrast, a family of four relying on bottled water commonly spends around 1,460 dollars per year, and some case studies document savings on the order of more than a thousand dollars in the first year after installing a home RO system, along with avoidance of thousands of plastic bottles.

In hard‑water regions, you should expect the following maintenance realities:

Sediment filters often need replacement every three to six months to protect the membrane, especially when hardness and other particulates are present. RO membranes typically last two to three years under average conditions. With high hardness and no softener, that lifespan can shrink; with a softener upstream, it can be preserved or extended. Softeners themselves require ongoing salt purchases and periodic regeneration, as well as occasional resin cleaning or replacement. There are also environmental considerations around brine discharge that you should check against local regulations. Hard water increases the need for regular inspection and cleaning. Technical articles on RO in industrial and ZLD systems stress the importance of cleaning before scale becomes severe, monitoring differential pressure, and using antiscalants judiciously to reduce chemical consumption while protecting membranes.

When you look at the whole picture, a combined softener plus RO system in a hard‑water home is an investment in both home infrastructure and health. You pay for equipment, salt, and filters, but you may save on energy, reduce appliance replacement, avoid bottled water purchases, and gain peace of mind around contaminants that a softener alone cannot touch.

A Practical Framework: Is RO Feasible For Your High-Hardness Home?

Bringing these threads together, here is a practical way to evaluate RO feasibility without falling into hype or fear.

Start by characterizing your water. Confirm whether your supply is from a city system or a private well. Obtain hardness data and a broad contaminant panel, either through your supplier’s reports or through direct testing. Pay particular attention to hardness, iron, manganese, sulfate, total dissolved solids, and health‑related contaminants like lead, nitrates, and PFAS.

Next, clarify your goals. Some homeowners mainly want to stop scale and protect appliances; others are primarily worried about drinking‑water safety; many need both. Industry guidance is clear that softeners are best at handling hardness, while RO is best at handling dissolved contaminants. If hardness is your only problem and your water tests clean for health concerns, a softener alone may be sufficient. If your water contains problematic contaminants, RO at least at the kitchen tap becomes much more compelling.

Then, choose the system type that matches your situation. In moderately hard city water, a high‑efficiency under‑sink RO system with solid pre‑filtration may be entirely feasible on its own. In harder well water with multiple issues, a softener plus a point‑of‑use RO is often the sweet spot. Whole‑house RO tends to be reserved for extreme cases such as very high TDS or specific industrial or medical needs in the home.

To help visualize common configurations, consider this simplified comparison.

Household scenario |

Water profile and concerns |

Likely feasible setup |

City home, moderately hard water, PFAS or lead detected |

Moderately hard municipal water, emerging contaminants at the tap |

Under‑sink or countertop RO at kitchen, optional softener for comfort |

Well home, clearly hard or very hard water |

Hardness plus iron, manganese, high dissolved solids possible |

Softener at entry plus RO at kitchen, with good pre‑filtration |

Well or city home, extreme TDS and multiple contaminants |

Very high mineral content and broad contaminant mix |

Softener plus carefully engineered RO, possibly whole‑house in rare cases |

Alongside configuration, pay attention to certifications and design details. Water quality professionals consistently recommend choosing RO systems that carry NSF or ANSI 58 certification for contaminant reduction and structural integrity. Independent lab testing, especially for PFAS or lead, adds another layer of confidence. The EPA’s WaterSense label now allows you to identify point‑of‑use RO systems that meet strict efficiency and performance criteria.

Material and build quality also matter for long‑term safety. Some experts recommend systems with American‑made components and BPA‑free plastics to minimize leaching of chemicals such as bisphenol A. Modern designs increasingly incorporate Wi‑Fi connectivity, smartphone apps, and integrated sensors to track filter life, monitor TDS, alert you to abnormal performance, and optimize water use.

Finally, plan for remineralization and health. In high‑hardness areas, you are trading a surplus of hardness minerals for very soft, low‑mineral water. It is wise to choose an RO system that includes remineralization or to add it yourself. This improves taste, helps support tooth and bone health over the long term, and aligns with broader public health guidance on avoiding exclusive, long‑term consumption of demineralized water without adequate minerals from other sources.

When RO In High Hardness Areas May Not Be The First Step

There are scenarios where RO is technically feasible but not the first investment I recommend.

If thorough testing shows that your water is hard but otherwise meets health‑based guidelines, and you are primarily frustrated with scale, soap scum, and appliance wear, starting with a good softener can deliver a large quality‑of‑life improvement at every tap. You can add RO later at the kitchen if your situation changes or if you want an extra safety barrier.

If you are on city water that is moderately hard but otherwise well managed, and your main concern is taste or chlorine odor, a high‑quality carbon filtration system may be sufficient and uses far less water than RO. The EPA’s efficiency guidance explicitly notes that RO is not the default solution for every treatment need and that filtration methods that waste little or no water are often preferable when they meet your goals.

And if you are not prepared for the maintenance and water‑waste implications of RO in a very hard‑water area, it is better to pause, address hardness with softening and targeted filtration, and revisit RO when you are ready for a more actively managed system.

Feasibility is not only about whether RO can physically operate; it is about whether it fits your household’s priorities, habits, and budget.

FAQ

Does an RO system soften water?

RO does remove hardness minerals along with many other dissolved solids, so the water at the RO faucet is very soft. However, RO is not a replacement for a softener because it typically treats only a single tap and does not protect your plumbing, water heater, or shower from scale. Hard‑water studies emphasize that using a softener upstream of RO in high‑hardness areas protects both the RO membrane and the rest of the home, while RO provides high‑purity drinking water at the kitchen.

Can I run an RO system without a softener if my water is only moderately hard?

Many homes with moderately hard city water run RO successfully without a softener, especially when hardness stays in the lower ranges and pre‑filtration is good. Support guidance from RO manufacturers suggests that keeping hardness below about seven grains per gallon is helpful for membrane life. In that band, a point‑of‑use RO system can be feasible on its own. As hardness rises beyond that, particularly on well water, the benefits of adding a softener upstream become much stronger.

Will drinking RO water harm my teeth or bones?

RO water is very low in minerals, including calcium, magnesium, and fluoride. Reviews of low‑mineral water have linked long‑term exclusive consumption of demineralized water to higher dental caries indices and potential impacts on bone mineral density, especially in children, if dietary minerals and fluoride are not otherwise sufficient. At the same time, most of your minerals come from food, and the contaminant‑reduction benefits of RO can be substantial. The most balanced approach in hard‑water areas is to use RO to remove contaminants and excess hardness, ensure adequate minerals through diet and remineralized water, and follow your dentist’s and physician’s guidance on fluoride and bone health.

In high‑hardness regions, the question is not whether RO can work; it is whether you are willing to give the membrane the support it needs. With honest testing, thoughtful pretreatment, high‑efficiency equipment, and smart remineralization, RO can be a powerful, science‑backed way to turn difficult hard water into safe, enjoyable hydration for your home.

References

- https://www.epa.gov/watersense/point-use-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/articles/reverse-osmosis-optimization

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10732328/

- https://www.purewaterent.net/water-hardness-and-its-impact-on-zld-systems/

- https://benfranklinplumbingkc.com/how-reverse-osmosis-system-works-cleans-your-homes-water/

- https://www.chunkerowaterplant.com/news/hard-water-reverse-osmosis-system

- https://mfwater.com/the-impact-of-hard-water-on-reverse-osmosis-systems/

- https://www.newater.com/how-to-choose-the-best-reverse-osmosis-system/

- https://www.simpurelife.com/pages/best-water-filter-for-hard-water?srsltid=AfmBOoqqhmMMdNKcAIblMBZkdRuf2_UMjmxsFRMhlakpOryxzibrSZcQ

- https://waterfilterguru.com/best-reverse-osmosis-system-reviews/

Share:

Maintenance Frequency for RO Systems in Dust Storm Areas

Wastewater Reduction Techniques Using Concentrated Water Circulation Technology