When a pump powers up but your taps still dribble, your home hydration routine takes a hit. Showers are weak, your smart filtration system keeps timing out, and the fridge dispenser or under‑sink filter never seems to catch up. As a smart hydration specialist, I see this pattern often in well systems, whole‑home filters, and booster pumps feeding kitchen drinking taps.

The good news is that “pump running but no pressure” is rarely a mysterious failure. In most homes, it comes down to a few predictable causes in the plumbing system, not just the pump itself. Guidance from organizations such as the Hydraulic Institute, Taco Comfort Solutions, and experienced well‑water specialists consistently shows that low‑pressure symptoms are usually solved by understanding the system, not just swapping equipment.

This article will walk you through what is really happening when your pump starts but pressure stays low, how to interpret the clues you see at the faucet, and how to make smart, health‑focused decisions that protect both your water quality and your equipment.

Pressure, Flow, and Your Home Hydration System

Before chasing parts, it helps to understand what “pressure” actually is in your system and why a running pump does not guarantee strong flow at the tap.

Pressure versus flow in plain language

Hydraulic experts at Machinery Lubrication explain that most fluid problems fall into two camps: pressure problems and volume problems. Pressure is the force your water can exert, like how hard it hits your hand at the faucet. Flow is the amount of water moving, like the number of gallons per minute.

The pump’s job is to move water. Pressure is created when this flow meets resistance, such as elevation, pipe friction, valves, and your plumbing fixtures. The Hydraulic Institute emphasizes that discharge pressure always reflects how the pump and the system interact, not the pump alone. If the pump is spinning but the water is allowed to slip back toward the source, leak out of the system, or churn with air instead of solid water, the pressure you read will be disappointing.

You can picture it this way. If a pump runs with the outlet closed, flow is nearly zero but pressure climbs up toward the pump’s limits. If the outlet is wide open through a large pipe, the pump moves a lot of water but pressure drops. A healthy system balances these two forces so your shower, kitchen tap, and filtration cartridges all see steady, comfortable pressure.

Why this matters for filtration and drinking water

Well‑designed point‑of‑use filters, whole‑home sediment filters, and membrane systems depend on enough inlet pressure to do their job. Fresh Water Systems points out that when pressure is low, you can see symptoms such as sputtering water, fluctuating flow, sediment in the lines, and a pump that runs constantly. Even when water is technically safe, low pressure can mean cartridges are underperforming, flow is too slow to be practical, and your pump is overheating or wearing out early.

For a smart home hydration setup, your goal is not just “water coming out.” You want consistent, adequate pressure so filters perform as designed and so you are not trading better water for higher stress on your equipment and energy bills.

Common Reasons a Pump Runs but Pressure Stays Low

Across case studies from Fresh Water Systems, the Hydraulic Institute, Stream Pumps, and field forums like Terry Love’s plumbing community, the same underlying issues appear again and again when pumps run but pressure will not build. The causes can be grouped into a few big buckets: suction‑side problems, discharge‑side leaks and bypasses, control and tank issues, pump sizing and condition, and simple measurement errors.

Suction‑side problems: the pump is “thirsty”

Most low‑pressure stories start on the suction side, where the pump draws water from a well, cistern, break tank, or storage reservoir. Technical guidance from the Hydraulic Institute and Stream Pumps highlights several recurring issues.

Air leaks on the suction line are a top suspect. JustAnswer’s plumbing experts point out that even a small leak at a union, fitting, or valve on the suction line can let air in without a visible water leak out. The pump then spins in a frothy mix of water and air, so it cannot build solid pressure. You may hear a rattling or crackling sound that PumpWorks and other industrial sources identify as cavitation or air entrainment.

Low water level at the source causes similar symptoms. If the well level drops or a break tank runs too low, the pump struggles to keep its suction eye flooded. Hydraulic Institute material explains that when pressure at the impeller eye falls far enough, vapor bubbles form and then collapse in higher‑pressure zones. The result is noise, vibration, and a dramatic drop in pressure and flow.

Clogged strainers or screens also show up frequently in low‑pressure diagnostics. Machinery Lubrication notes that suction strainers are “out of sight and out of mind” inside the reservoir and are often neglected. When they plug, the pump cannot take in enough water to maintain its output. The flow may drop gradually with a rising whining sound, or suddenly if sludge or debris shifts into the screen. In residential systems, a partially blocked well screen or intake filter can mimic exactly the same pattern.

Excessive suction lift is another subtle enemy. If the pump sits too far above the water level or uses undersized suction piping with many fittings, the suction pressure can fall below what the pump requires, especially at higher flow. Stream Pumps emphasizes that many multistage and booster pumps that “just will not build head” are actually being asked to pull harder on the suction side than they were designed to.

As a real‑world example, consider a jet pump on a deep well that used to deliver around 50 to 60 psi but now stalls at about 20 psi. A homeowner on a well forum described exactly that behavior: the pump ran nonstop but could never rise above roughly 20 psi. In practice, that kind of ceiling is a strong hint that suction conditions have deteriorated or that air or debris is limiting what the pump can draw in, long before you assume the pump itself is worn out.

Discharge‑side leaks, bypasses, and “short circuits”

Even when the suction side is healthy, water can quietly escape or loop back toward the source instead of pushing into your home.

One common culprit is a partially open bypass or relief path. In expert troubleshooting for a Grundfos pump that would only reach about 20 psi, JustAnswer noted that an open bypass or mis‑set relief valve can recirculate water back to the tank, making the pump appear weak even though it is moving plenty of water. All that flow is simply not reaching the pressure gauge that feeds your home’s fixtures and filters.

Leaks on the discharge line have a similar effect. Stream Pumps calls out discharge leaks and malfunctioning valves as prime causes of chronic low pressure. If a buried line between the well and the house has a break, or if a valve is stuck partially closed or worn so badly that it bypasses internally, the pump will keep running as it struggles against a moving target. You may notice damp soil near the line, unexplained water usage, or a pump that never quite shuts off.

In more advanced systems, solenoid‑controlled directional valves and multi‑zone manifolds can also leak internally. Machinery Lubrication describes a method where technicians isolate valves, cap ports, and use a hand pump to see whether pressure holds for at least a minute. If it drops immediately, the valve is bypassing internally. In residential systems, the same idea applies on a simpler level: if you close off branch lines and see pressure stabilize, but it falls when a certain zone is opened, you have narrowed down where the “short circuit” may be.

The pressure switch and tank: small parts, big impact

In home well and booster systems, the pressure switch and pressure tank are the brains and buffer of the system. Fresh Water Systems emphasizes that many “bad pump” calls are actually pressure switch or tank failures in disguise.

The pressure switch senses system pressure and tells the pump when to start and stop. If its contacts weld shut or the spring setting drifts, the pump may run constantly or cut out at the wrong time. A mis‑set switch that is demanding more pressure than the pump can ever reach is a classic recipe for a pump that runs without success. JustAnswer’s experts warn that if the cut‑off pressure is set higher than the pump’s maximum rating, the pump will simply run until it times out or overheats.

The pressure tank adds a cushion of compressed air so the pump does not have to switch on and off with every glass of water. When the internal bladder fails, water and air mix, and the tank no longer stores usable pressure. Fresh Water Systems notes that this leads to rapid cycling and “waterlogging,” which can make the pump run constantly without the pressure gauge ever settling in a healthy range. A telltale sign is water coming out of the Schrader valve on top of the tank instead of air when you briefly press it.

Undersized or very old tanks, like the small horizontal tank described in a DoItYourself forum case, can worsen low‑pressure symptoms. The homeowner in that case saw pressure stuck around 20 psi while the pump labored continuously. The system had an aging gauge, small tank, and several minor leaks. Upgrading to an appropriately sized modern pressure tank and a fresh, correctly set pressure switch often transforms both pressure stability and pump longevity.

Pump sizing, rotation, and internal condition

Sometimes the problem really is the pump, but the pattern is often different than most homeowners expect.

Oversized pumps are common in both industry and residential upgrades. Vissers Sales notes that many pumps are selected with extra capacity “just in case,” then throttled with valves to hit the desired flow and pressure. That wastes energy and can move the pump away from its best‑efficiency point. Terry Love’s plumbing forum offers a useful cautionary story: upgrading from a modest 7 gallon‑per‑minute pump to a much larger unit aimed at supplying sprinklers solved one issue but created another. The larger pump could cycle itself to death without system changes and required special controls like a cycle‑stop valve or variable‑speed drive to stay healthy.

Undersized or mismatched pumps can show up as low pressure as well. JustAnswer’s Grundfos case highlights that if you replace a pump with a smaller model or with one whose performance curve cannot reach your pressure switch setting, you will never see the gauge climb to the desired cut‑off. The pump will dutifully run and run without ever quite getting there.

Incorrect rotation direction sounds exotic but is surprisingly common with new installations. The Hydraulic Institute notes that a three‑phase motor wired backwards will spin the pump the wrong way. The symptoms are loud operation and only about half to two‑thirds of the expected pressure and flow. Fortunately, this is correctable by swapping two motor leads, but it is a reminder that “new” and “properly set up” are not the same thing.

Internal wear and damage add a slower‑burn dimension. PumpWorks and Stream Pumps both describe how erosion, corrosion, and worn wear rings or impellers gradually steal pressure. The pump’s internal clearances grow, so more water slips backward inside the casing instead of being pushed forward. The pump may still start and move some water but can no longer hit the higher pressure it once did, especially under load.

System design and gauge placement: when the numbers lie

Sometimes the pump and piping are functioning as designed, but you are reading the wrong number or expecting the wrong thing.

Taco Comfort Solutions, which supports commercial hydronic systems, reports that 80 to 90 percent of “pump problems” they investigate turn out to be system issues or measurement misunderstandings. The Hydraulic Institute also reminds users that gauge location matters. A pressure gauge mounted far from the pump, on a smaller pipe, or on an upper floor will show lower pressure than a gauge right at the pump discharge because of elevation and friction losses.

As a simple example, water specialists point out that roughly 10 psi of water pressure is equivalent to a column of about 23 feet. If your pump is generating around 60 psi at the basement discharge, it is perfectly normal to see something closer to 50 psi at a second‑floor bathroom once you account for the vertical rise and pipe friction. That is not a failing pump; it is physics.

Mis‑calibrated or failing gauges also cause a lot of confusion. DoItYourself forum participants often recommend replacing a questionable, decades‑old gauge with an inexpensive new one or temporarily attaching a known good gauge to an outside spigot. If a new gauge shows different readings than the old one, you may have just solved a “mystery” low‑pressure complaint without touching the pump.

A Practical, Health‑Focused Troubleshooting Path

Pump technicians who write for Machinery Lubrication and Taco stress one theme over and over: resist the urge to swap parts randomly. Instead, follow a simple, logical progression that protects both your equipment and your water access. As a homeowner, you can safely do the early, low‑risk checks and then decide when it is time to call in a professional.

Clarify what you are feeling at the tap

Start by paying close attention to your symptoms and writing them down. Note whether the pump turns on when the pressure drops and whether it turns off at all. Watch the pressure gauge as someone opens a fixture. If pressure falls sharply to around 20 psi and the pump never climbs above that level, you are seeing the same pattern several well owners have described when the suction side is restricted or there is a major leak.

Try to remember whether the problem appeared suddenly or gradually. A sudden change after construction, a power outage, or a plumbing repair may point toward a mis‑set switch, a disturbed suction line, or a valve that was left partially closed. A slow decline over months suggests sediment buildup, wear, or a well level that is dropping over time.

Listen to the pump while it runs. A smooth hum with little vibration suggests a mechanical issue elsewhere, while sharp crackling, rattling, or a strained whine points toward air entrainment, cavitation, or blocked suction. PumpWorks and the Hydraulic Institute both flag those sounds as warning signs that fluid is not reaching the impeller as it should.

Check the easy, safe items first

Once you have a clear description of what is happening, move to the simplest checks that do not require opening electrical boxes or disassembling equipment.

Look for obvious leaks, damp spots, or continuously running toilets and fixtures inside the home. Fresh Water Systems notes that chronic leaks or excessive demand can keep a pump running constantly and hold pressure down even when the pump itself is healthy.

Inspect and, if needed, replace accessible filters. Whole‑home sediment filters and under‑sink cartridges can clog with sand, rust, or mineral buildup, especially on well systems. Fresh Water Systems specifically recommends sediment pre‑filters and softeners to protect both plumbing and pressure. A clogged cartridge can easily create the impression of a weak pump while the actual problem is only a few inches of dirty filter media.

Observe the pressure switch externally. Without opening it, you can often see whether the small tube feeding it is kinked or corroded, or whether the switch housing is rusted and loose. If it is clearly in poor condition and the pump runs erratically, replacing the switch is usually a modest investment that can restore proper control.

Check the pressure tank’s behavior. Turn off power to the pump, relieve system pressure at a faucet, and use a tire gauge on the tank’s air valve. If water comes out of that valve, Fresh Water Systems is clear that the bladder has failed and the tank needs replacement. If air pressure is far from the intended setting relative to your cut‑in pressure, the tank may need to be adjusted or serviced.

If you have safe access, glance at the suction line from the well or storage tank. Look for loose clamps, weeping joints, and sections that could trap air. JustAnswer’s case studies show that tightening or resealing a small suction‑side fitting has restored pressure for many homeowners without touching the pump.

Decide when to call a professional

Some symptoms are strong indicators that you are beyond simple homeowner maintenance. Persistent pressure that never rises above about 20 psi, loud cavitation noises, or a pump that overheats and trips out repeatedly warrant professional diagnostics.

Suspected gas in the water is an immediate red flag. Fresh Water Systems warns that while rare, gas pockets in a well are hazardous and require prompt professional attention, especially if you notice a strong odor or visible bubbling in fixtures.

If you recently upgraded to a larger pump or added significant filtration and now see cycling, surging, or erratic pressure, a designer or pump specialist should review the system. Taco’s commercial troubleshooting experience shows that added strainers, valves, or piping changes often introduce unexpected resistance that pushes systems off their original design point. A similar principle applies at the residential scale.

A qualified technician can perform more advanced checks that mirror those described by Machinery Lubrication and the Hydraulic Institute: testing pump output with flow meters, isolating sections of piping, confirming motor rotation, and comparing field data to the pump’s performance curve. The goal is not just to restore pressure but to do so in a way that protects pump life and energy efficiency.

Smart Hydration Systems: Special Considerations

Modern home hydration setups go beyond a simple well and tank. Under‑sink reverse‑osmosis units, multi‑stage filtration manifolds, UV disinfection, and fridge taps all introduce their own pressure needs.

Under‑sink and point‑of‑use filters

These systems often include several cartridges in series. Every stage adds some resistance, so inlet pressure matters. When pressure is low, the faucet may produce only a slow trickle, and the system may not deliver water at the rate you expect.

Fresh Water Systems emphasizes that mineral and sediment buildup in plumbing and fixtures can suppress flow even if the pump is otherwise healthy. Installing and maintaining a suitable sediment filter ahead of delicate cartridges protects both pressure and water quality. If your pump runs but the filtered tap is weak while unfiltered outside spigots are stronger, you likely have restriction in the filtration path rather than a failed pump.

Whole‑home filtration and softeners on wells

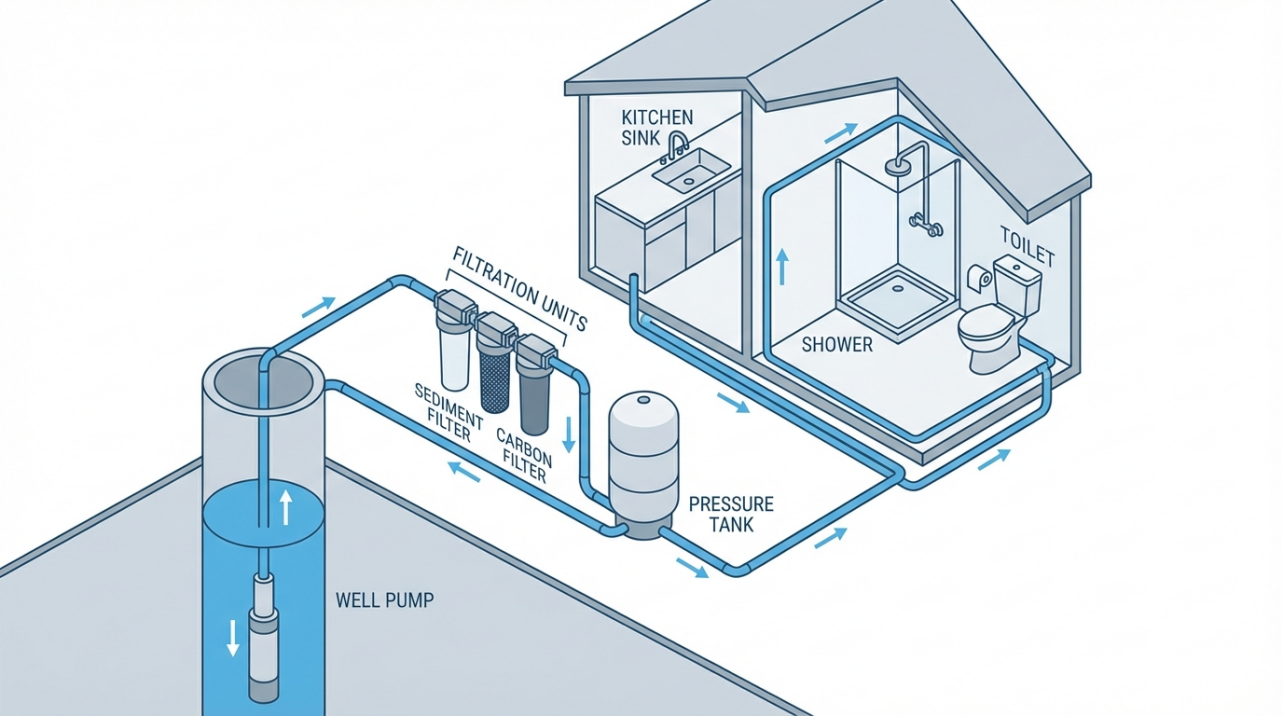

In well homes, it is common to combine a submersible or jet pump with a pressure tank, a sediment filter, and often a water softener. When any of these components are undersized, clogged, or mis‑configured, the pump can appear weak.

For example, a very fine sediment filter rated for low flow that is installed on an entire house can create large pressure drops when multiple fixtures run. Fresh Water Systems recommends whole‑home sediment filters sized for adequate flow and paired with softeners tuned to the household’s hardness level. If your pump starts and your gauge shows decent pressure at the tank but distant showers sag, it is worth evaluating the filters and softener valve before assuming the pump is at fault.

Booster pumps for multi‑story homes and luxury fixtures

Booster pumps are often added to improve pressure in multi‑story homes, apartment‑like layouts, or to support spa showers and multiple body sprays. Mawdsley’s booster pump guidance notes that when these pumps fail to start or make unusual noise, entire sets of outlets can lose pressure.

From a hydration standpoint, you may notice that the kitchen drinking tap on a higher floor is the first to show problems when pressure falls. That is because it sits at the end of a higher, more restrictive path. Ensuring that the booster pump is correctly powered, that its break tank (if present) is full, and that the installation follows manufacturer recommendations on pipe sizing and vibration isolation will protect both performance and noise levels.

Quick Reference: Clues and Likely Causes

The table below summarizes how several common clues relate to underlying causes, based on the combined guidance from Fresh Water Systems, the Hydraulic Institute, Stream Pumps, JustAnswer, and other technical sources.

Likely cause or area |

Common clues you notice |

What this means for your water |

Smart first steps |

Suction‑side air leak or low water level |

Pump runs but pressure stalls around a low value; crackling or rattling sounds near pump; issue worse when using high flow |

Inconsistent pressure and possible sputtering at taps; risk of pump damage from cavitation |

Inspect visible suction fittings and tank levels; call a pro if noise is severe or the source is a deep well |

Clogged screen or filter |

Gradual loss of pressure over weeks or months; filters look dirty; pump sounds strained at higher flows |

Slower fill times for pitchers and appliances; filters may be bypassed or overloaded |

Replace or clean sediment filters and strainers; maintain a pre‑filter before sensitive cartridges |

Faulty pressure switch or tank |

Pump runs constantly or cycles rapidly; gauge never reaches normal cut‑off; tank feels “solid” when tapped |

Stress on pump and electronics; erratic pressure at fixtures and filters |

Test or replace the pressure switch; check tank air charge and bladder condition; upgrade undersized tanks |

Discharge leak or bypass path |

Pump starts normally; pressure rises slightly but will not hold; unexplained water usage or damp areas |

Wasted water and energy; poor pressure even with modest use |

Inspect visible piping, yard, and fixtures for leaks; have buried lines and valves tested professionally |

Mis‑sized or incorrectly wired pump |

Low pressure after a recent pump replacement; loud pump; energy bills higher than expected |

Poor performance from hydration systems even with new equipment |

Verify pump model versus system needs; have a technician confirm motor rotation and compare readings to pump curves |

This table is a guide, not a diagnosis. The goal is to give you a clearer, science‑backed picture of how the symptoms you feel at the tap connect to real mechanical causes.

FAQ: Home Hydration When the Pump Won’t Build Pressure

Is it safe to keep running a pump that never reaches cut‑off pressure?

Continuous running at low pressure is hard on a pump. Fresh Water Systems warns that constant running from issues like leaks, low well levels, or faulty switches can shorten pump life and raise electricity bills. Field experience echoed on Terry Love’s forum shows that pumps subjected to frequent cycling or long, strained runs tend to fail much earlier than properly controlled units. If your pump cannot reach cut‑off and runs for long stretches, it is wise to stop experimenting and have the system evaluated before damage becomes permanent.

Will installing a “stronger” pump fix low pressure at my smart filtration tap?

Upgrading to a bigger pump without addressing system issues rarely solves the problem and can create new ones. Vissers Sales points out that oversized pumps often run inefficiently, wasting energy as they are throttled to avoid over‑pressurizing the system. Terry Love’s forum discussion about moving from a modest pump to a much larger one illustrates how a bigger pump can cause severe cycling unless other components are resized or controls like cycle‑stop valves or variable‑speed drives are added. In many homes, optimizing suction conditions, fixing leaks, and right‑sizing filters restores healthy pressure without oversizing the pump.

How does low pressure affect the performance of my filtration and hydration systems?

Low pressure is most obvious as slow flow, but it also affects how filters interact with your water. Fresh Water Systems notes that sediment and mineral buildup in plumbing and fixtures restrict flow and can lead to symptoms like sputtering and constant pump running. When pressure is low, your filtration system may not deliver water at the rate you expect, and cartridges may see uneven loading. Restoring proper system pressure and keeping pre‑filters clean helps your hydration setup operate as it was designed, giving you consistent access to clear, good‑tasting water.

Reliable pressure is the quiet partner of every healthy hydration system. When your pump starts but the pressure is not there, you are not just fighting an annoyance; you are protecting the heart of your water supply and the everyday rituals built around it. By understanding how pressure, flow, and system components work together, and by acting methodically with trusted technical guidance, you give both your equipment and your own hydration habits the steady support they deserve.

References

- https://water.mecc.edu/courses/ENV115/lesson18b.htm

- https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/CFPC/PJ-Norwood/Basic-Pumps-Student-Manual.pdf

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-06/documents/Pump-Operation.pdf

- https://documents.fresno.gov/weblink/0/edoc/2047872/313.005%20-%20Standard%20Pump%20Operation.pdf

- https://www.montgomerycountymd.gov/mcfrs-psta/Resources/Files/Driver/20150325/UnitKBEngines/Engine_Manual/Training%20Supplements%20Spring%202019/Module%204%20-%20Centrifugal%20Fire%20Pumps%205_12_20.pdf

- https://www.pumps.org/2021/09/23/why-pump-pressure-lower-than-expected/

- https://www.mawdsleyspumpservices.co.uk/7-common-problems-with-booster-pumps-and-how-to-fix-them/

- https://www.globalpumps.com.au/blog/how-to-increase-discharge-pressure-of-centrifugal-pumps

- https://dropconnect.com/well-pump-running-but-not-building-pressure/

- https://www.ingco.com/blog/how-to-remove-airlock-in-water-pump

Share:

Understanding Why Your RO System Sometimes Refuses to Operate

Understanding Variability in TDS Meter Readings and Measurement Techniques