As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time looking not just at what a reverse osmosis system removes, but at how efficiently it does the job. Many people today ask about waste ratios, energy use, and long‑term reliability. A less obvious but important piece of that puzzle is where the main pump sits in relation to the filters: before them or after them. In other words, whether you are working with a pre‑pump or a post‑pump RO layout.

Most product brochures never explain this in plain language. This article walks through what the research says about RO efficiency, how pump placement interacts with pre‑filtration and membrane performance, and what actually matters when you are choosing or upgrading a home or light‑commercial RO system.

Throughout, I will draw on findings from manufacturers and technical sources such as Apex Water Filters, Axeon Water Technologies, Cannon Water Technology, the Water Quality Association, Veolia’s water technology team, the U.S. Department of Energy, MDPI’s Water journal, and peer‑reviewed RO optimization studies, then translate that into practical guidance you can use under your own kitchen sink.

RO Basics: Pressure, Membranes, And Pre‑Filtration

Reverse osmosis is a pressure‑driven process. As Apex Water Filters and several technical overviews explain, water is pushed against a semi‑permeable membrane hard enough to overcome natural osmotic pressure. The membrane allows water molecules through while rejecting most dissolved salts, heavy metals, organic chemicals, and many microorganisms. Compared with simple gravity or carbon filters, RO operates at a molecular level and can remove up to about ninety‑five to ninety‑nine percent of dissolved solids according to summaries from Puretec and industrial suppliers like Veolia.

Instead of straining everything in one direction, modern RO systems use cross‑flow. Feed water sweeps along the surface of the membrane. Part of it becomes low‑mineral product water, while the rest becomes a concentrated reject stream that carries away the contaminants. This is why some water always goes to drain when an RO unit runs.

Research summarized by Fresh Water Systems and other sources stresses that this is not “pointless” waste; it is the mechanism that keeps the membrane from clogging instantly.

The High‑Pressure Pump: Heart Of A Pumped RO System

In any pumped RO system, the high‑pressure pump is the central energy consumer and performance driver. Atmospheric or gravity‑fed devices cannot generate the pressure that genuine RO requires. A technical article from Atmosfer Makina describes the pump as the core enabling component: without sufficient and stable pressure, even the best membrane cannot achieve the high purity and production rate users expect.

In large desalination or industrial installations, pumped RO units routinely produce thousands of gallons of permeate per day and treat difficult feeds such as brackish well water or seawater. According to studies summarized in MDPI’s Water journal and in a seawater RO modeling paper published in a medical research library, the RO train itself often accounts for about eighty percent of a desalination plant’s energy use. The U.S. Department of Energy reports that brackish‑water RO in large facilities typically consumes around 2 to 9.5 kilowatt‑hours per 1,000 gallons of product water, while seawater RO commonly falls in roughly the 11 to 23 kilowatt‑hours per 1,000 gallons range.

These numbers are for big municipal or industrial plants, not kitchen systems, but the physics is the same. Most of the electrical energy goes into running the high‑pressure pump. That is why pump efficiency, correct sizing, and pressure control show up repeatedly in optimization guidance from both the Department of Energy and academic modeling work.

Pre‑Filtration: Protecting Membranes And Stabilizing Performance

Before feed water reaches the membrane, it goes through pre‑filtration. Axeon Water Technologies describes pre‑filtration as the first stage of an RO system: water passes through sediment filters and carbon filters, and sometimes a softener, to remove suspended solids, rust, dirt, and key chemicals such as chlorine and chloramines.

Sediment cartridges are the first physical barrier. In residential systems documented by WECO and Cannon Water Technology, the sediment stage typically captures sand, silt, precipitated mineral particles, and insoluble iron oxide down to about five microns. Systems may even use multiple sediment stages with progressively tighter ratings so that larger particles are removed without instantly clogging a fine filter.

Carbon pre‑filters then handle chemistry. Chlorine and chloramines are essential for disinfection in city water, but they are harsh on the thin‑film composite RO membranes that dominate modern home and commercial units. Axeon and WECO note that membrane performance can deteriorate after a certain cumulative exposure to free chlorine. Granular activated carbon or carbon block filters remove these oxidants, along with volatile organic compounds and many taste and odor compounds, before they ever reach the membrane.

The combined effect of sediment and carbon pre‑filtration is significant. As Axeon and the Water Quality Association emphasize, it keeps the membrane surface cleaner, slows fouling and scaling, helps maintain the designed pressure and flow conditions, reduces the frequency of cleanings and replacements, and even improves sensory quality by stripping out substances responsible for bad taste and smell. Because the membrane works against a lighter contaminant load, the system can often produce water at a faster rate and with less energy per gallon, particularly in larger installations where pump power is a major line item.

What “Pre‑Pump” And “Post‑Pump” RO Layouts Mean

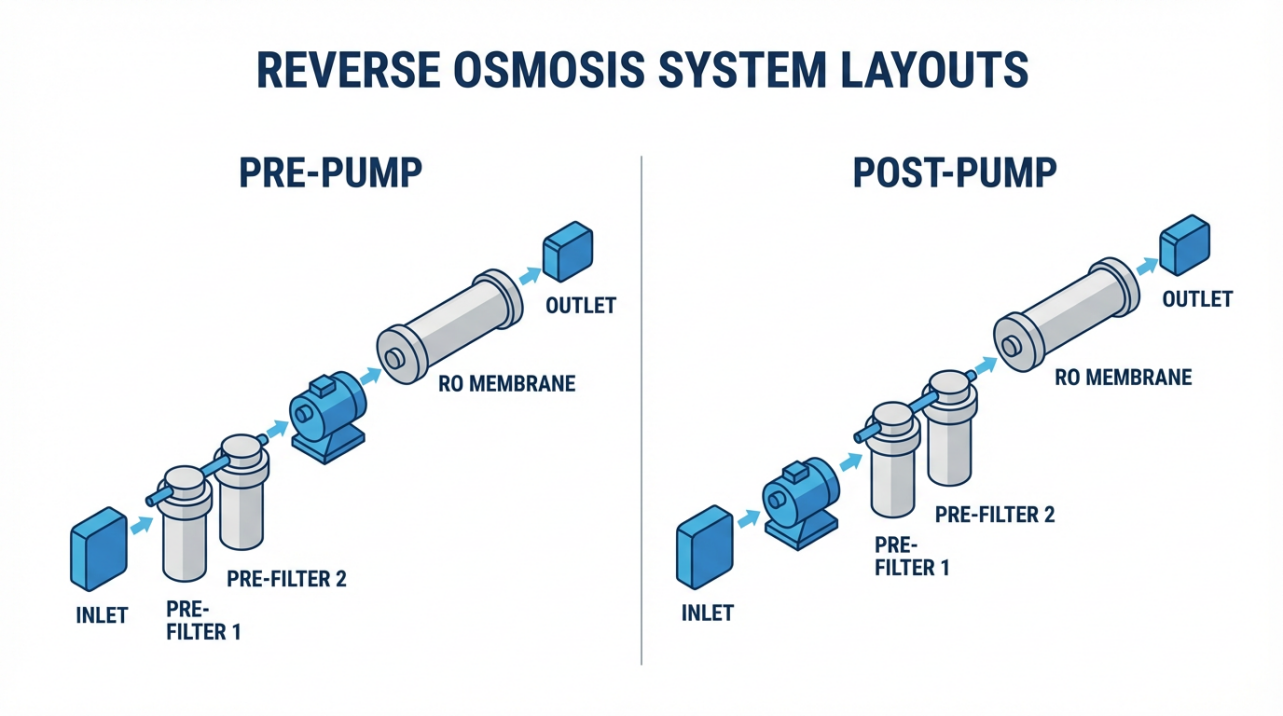

Most RO diagrams show the same basic building blocks: feed connection, pre‑filters, high‑pressure pump in pumped designs, RO membrane, storage tank or distribution header, and post‑filters. What changes is the order and side of the pump where those pre‑filters live.

There is no single industry‑standard vocabulary for this, so for clarity in this article:

I will use the term pre‑pump RO layout to mean a system where the main sediment and carbon pre‑filtration stages sit upstream of the high‑pressure pump. The water flows from the cold‑water supply to the pre‑filters, then into the pump, then through the RO membrane, and finally into the storage tank and post‑filters.

I will use the term post‑pump RO layout to mean a system where the high‑pressure pump comes first. Water flows from the supply into the pump, then through the pre‑filters on the high‑pressure side, then through the membrane and onward to storage and post‑filtration.

In real products, there are hybrids. Some industrial designs include a coarse strainers or cartridge filters before the pump and finer treatment stages after it. Home systems with booster pumps often incorporate the pump between sediment and carbon stages or between the last pre‑filter and the membrane. However, distinguishing between these two idealized layouts helps untangle how pump placement interacts with efficiency.

It is worth noting that at least one manufacturer article whose title was captured in the research, from Brother Filtration, explicitly asks why pre‑filtration is needed before a high‑pressure pump. That fits the broader pattern in industrial water treatment where protecting pumps from grit and reactive chemicals is considered just as important as protecting membranes.

Energy Efficiency: Does Pump Placement Really Change Power Use?

To understand energy differences between pre‑pump and post‑pump layouts, it helps to separate three ideas: how much pressure the membrane needs, how efficient the pump is at providing that pressure, and how fouling changes both over time.

What Actually Drives RO Energy Use

Technical guidance from the U.S. Department of Energy and modeling studies cited in MDPI’s Water journal make two consistent points.

First, the required pressure is mainly set by feed water salinity and desired recovery. For seawater, large plants may run around the six hundred to twelve hundred pounds per square inch range, while brackish water systems operate at much lower pressures. Household under‑sink units that treat municipal water typically need something on the order of forty pounds per square inch of feed pressure or higher to operate well according to general information compiled from Wikipedia and home RO guides; below that, they often rely on a booster pump.

Second, for a given pressure and flow, the biggest variable in energy consumption is how close the high‑pressure pump operates to its best efficiency point. A seawater RO study using a detailed pump and membrane model found that several very different design configurations all achieved specific energy use below about two kilowatt‑hours per cubic meter, which is roughly seven and a half kilowatt‑hours per 1,000 gallons, as long as the pumps stayed in their optimal operating window with the help of variable‑frequency drives. The worst energy outcomes appeared when the pump was forced to run far away from its peak efficiency.

In other words, how efficiently you generate the pressure usually matters more than small differences in layout.

Pre‑Pump Layout: Energy Implications

In a pre‑pump layout, sediment and carbon filters see line pressure from the city or well. They introduce some pressure drop on the suction side of the high‑pressure pump. The pump must overcome that drop in addition to the pressure needed across the membrane.

At first glance, this sounds less efficient. However, research summarized by Axeon and the Department of Energy shows that robust pre‑treatment lowers fouling and scaling on the membrane and can reduce the pressure required to maintain a given production rate over time. It also protects flow restrictors and other small passages from plugging with particles.

When the pump receives water that has already been stripped of most grit and a large fraction of oxidants and organics, it tends to stay cleaner internally as well. That helps the pump’s internal hydraulics remain close to their design condition. Combining reasonably clean feed with a properly sized pump and, in larger systems, a variable‑frequency drive, allows the system to maintain design flux and recovery with smaller increases in pressure as membranes age.

Put simply, any small extra pressure the pump must provide to make up for the suction‑side pre‑filters can often be offset by slower fouling and a more stable operating point. The net effect is that a well‑designed pre‑pump layout can hold its efficiency curve much longer between services, especially on water with significant particulate or oxidant load.

Post‑Pump Layout: Energy Implications

In a post‑pump layout, the high‑pressure pump sees relatively raw feed water. The primary pre‑filters live on its discharge side, so they are not available to remove sand, rust, or debris before it reaches the pump impeller and seals.

From a hydraulic standpoint, the pump still has to generate enough pressure to overcome the membrane plus the pressure drop of the filters wherever they sit. Moving the filters to the discharge side does not magically reduce the total head required. What can change is how fouling affects the pump itself.

If sediment and scale build up inside the pump or on its inlet, internal flow passages change shape. That can push the pump away from its best efficiency point in the same way heavily fouled membranes or scaled energy‑recovery devices do in large seawater plants. The Department of Energy’s RO optimization guidance highlights that fouling anywhere in the high‑pressure train raises differential pressures and energy use. Although their examples focus on membranes and pre‑filters, the same logic applies to pump internals.

Because we do not have controlled, comparative test data in the notes specifically measuring pre‑pump versus post‑pump layouts in homes, it would be incorrect to assign a universal percentage savings to one or the other. What the available research does support is this principle: layout that reduces fouling on both membranes and pumps helps keep pressure and energy closer to the original design over the life of the system. That is why industrial vendors discuss pre‑filtration before high‑pressure pumps and why so much engineering effort goes into maintaining clean, stable operating conditions.

Water Efficiency: Waste Ratios, Recovery, And Pump Layout

When people talk about RO “efficiency,” they usually mean water use at least as much as energy use. Traditional under‑sink RO systems are often criticized for sending several gallons of water to the drain for every gallon of drinking water produced.

Home RO guides summarized by Fresh Water Systems note that typical older designs waste about three to four gallons of concentrate for every gallon of purified water. WECO’s component article echoes this, explaining that many standard RO systems produce around four gallons of waste per gallon of permeate when supplied with city water pressure above about seventy pounds per square inch. These ratios are controlled mainly by the membrane design and the flow restrictor on the drain line.

Newer technologies and smarter pump control can do better. WECO mentions water‑saving membranes that can achieve roughly a one‑to‑one ratio. Independent lab testing described by Water Filter Guru found that the AquaTru countertop system reaches about a four‑to‑one recovery ratio, meaning only one gallon of water is wasted for every four gallons purified, while some modern under‑sink systems with high‑efficiency pumps and optimized hydraulics can also reach a one‑to‑one ratio under real‑world conditions.

Axeon’s discussion of pre‑filtration highlights another important angle: clean, well‑protected membranes require less energy and can produce water faster, which in many designs translates into higher practical recovery and less frequent flushing. The U.S. Department of Energy notes that better pretreatment often allows operators to push recovery higher without hitting scaling limits, which further reduces wastewater volume for a given permeate output.

So where does pump placement come in? Again, the layout itself is not as powerful a lever as membrane type, recovery setting, and overall pre‑treatment quality, but it interacts with them.

In a pre‑pump layout, the pump and membrane both see water that has already been stripped of most large particles and key oxidants. That slows the rate at which the membrane plugs and can delay the point where operators or built‑in controllers need to increase flushing frequency or accept a lower recovery ratio. Over months and years, that stability helps keep the waste ratio close to the original specification.

In a post‑pump layout with little or no pre‑filtration ahead of the pump, any solids or hardness scale form inside the high‑pressure plumbing before the filters. That can accelerate pressure loss and fouling upstream of the membrane. Controllers that react to pressure changes may respond with more aggressive flushing or conservative recovery settings, which increases total water sent to drain over the life of the system even if the starting ratio was similar.

The research notes do not provide direct side‑by‑side data for these two layouts in residential systems, so the safest conclusion is that pump placement mainly influences how quickly a system drifts away from its design water efficiency, especially on more challenging feed water. The largest determinant of waste ratio remains the combination of membrane technology, flow restriction, and maintenance.

Component Stress, Noise, And Maintenance

From a homeowner’s perspective, efficiency is also about how often something breaks and how disruptive it is when it does. Here, pre‑filtration and pump placement have very tangible impacts.

WECO’s breakdown of home RO components points out that standard filter housings, especially clear ones made from styrene acrylonitrile, often have maximum pressure ratings around seventy‑five pounds per square inch. They even recommend an optional pressure regulator to protect these housings from high pressure and water hammer. That reminder is important whenever filters are on the discharge side of a pump.

In a pre‑pump layout, the sediment filter sees only the line pressure from your plumbing. Its main job is catching sand, grit, and insoluble iron before those particles can reach anything delicate, including the pump and the membrane. With a typical recommended replacement interval of about six months for standard under‑sink cartridges, and about three months for very small cartridges, the filter is inexpensive insurance.

When the pump receives this pre‑filtered water, abrasive wear on the impeller and seals is reduced. In practice that often means quieter operation, fewer leaks, and longer pump life, all of which contribute to what might be called “practical efficiency” because fewer parts need to be replaced and service calls are less frequent.

In a post‑pump layout, the pump must handle raw feed water. Any sediment that would have settled harmlessly in a pre‑filter now slams into the pump’s inlet and internal surfaces at high velocity whenever the system runs. Over time this can lead to increased noise and vibration, reduced hydraulic efficiency, and mechanical wear that shows up as leaks or sudden loss of pressure. Filters on the discharge side then have to be designed to tolerate full pump pressure as well, which is why understanding component ratings is critical.

Membrane life is another key piece of the efficiency picture. Axeon and the Water Quality Association explain that good pre‑filtration extends membrane life by taking the brunt of the contaminant load. Many POU membranes in typical home systems are designed to last on the order of two to five years depending on feed quality and usage when properly protected. If the membrane has to play “garbage filter” as well as fine purifier because upstream filtration is weak or poorly placed, its life shortens and it becomes more prone to irreversible fouling and scaling. That not only raises replacement costs but also tends to push energy use and waste ratios upward as pressure must be increased to maintain performance.

Whatever the layout, all sources converge on one practical recommendation: keep up with pre‑filter replacement. Axeon suggests inspecting pre‑filters every six to twelve months and replacing them as needed based on your water quality. WECO recommends at least six‑month sediment replacements in typical systems and three months in compact ones. The Water Quality Association echoes similar intervals. Skipping those small, low‑cost components is one of the fastest ways to turn a reasonably efficient RO system into an energy‑hungry and water‑wasting one.

Side‑By‑Side Comparison: Pre‑Pump vs Post‑Pump RO

The table below summarizes the main differences in how each layout tends to behave, based on the technical points discussed above.

Aspect |

Pre‑pump RO (filters before high‑pressure pump) |

Post‑pump RO (filters after high‑pressure pump) |

Pump protection |

Pump receives water that has already passed through sediment and carbon stages, which reduces grit and oxidant exposure and can extend pump life. |

Pump handles raw feed water so abrasive particles and certain chemicals reach the impeller and seals, which can increase wear. |

Membrane protection and fouling |

Sediment and carbon filtration protect both pump and membrane; fouling tends to be slower and operating pressure stays closer to design longer when maintenance is done on schedule. |

Filters still protect the membrane, but pump‑side fouling can affect pressure and flow conditions before water reaches the membrane. |

Energy behavior over time |

Any small suction‑side pressure loss is often offset by reduced fouling, helping the pump operate nearer its best efficiency point over the long term. |

Internal pump fouling or upstream scaling can move the pump away from its peak efficiency and may force higher pressures to maintain production. |

Water efficiency over time |

Stable pressures and cleaner membranes help maintain the designed waste ratio and reduce how often aggressive flushing is required. |

Greater risk that fouling upstream of the membrane leads to more flushing and drift away from the original waste ratio. |

Component stress |

Filters see line pressure; housings need to handle municipal or well pressure but not full pump discharge. |

Filters on the discharge side must be rated for full pump pressure; housings and fittings experience higher mechanical stress. |

Typical use cases |

Often favored in industrial guidance that emphasizes pre‑filtration before high‑pressure pumps and in home systems where booster pumps are added after existing pre‑filters. |

More likely in compact, integrated skids where pump and filters are packaged tightly; specific patterns vary by manufacturer and are not always documented in consumer materials. |

This comparison reflects general engineering logic and the qualitative guidance contained in the research notes rather than controlled side‑by‑side testing of consumer units. Actual performance will depend on the specific pump, membrane, controls, and how carefully the system is maintained.

How To Choose For Your Home Or Small Business

For most households, you will not be moving pumps and filters around yourself. The decision point is which type of system to buy and how to evaluate the specifications that manufacturers and installers give you.

The first question is whether you need a pumped RO system at all. Information collected from Wikipedia and manufacturer literature indicates that domestic RO membranes typically require feed pressures around forty pounds per square inch to work well. If your incoming pressure is comfortably above that and you are using a modest under‑sink system, an un‑pumped design with good pre‑filtration can be both simple and efficient, especially if it uses a modern low‑waste membrane.

If your pressure is low, you want tankless on‑demand production, or your water has very high dissolved solids, then a pumped system usually becomes the more efficient choice in practice. Without enough pressure, an un‑pumped RO unit can produce water painfully slowly and may even waste more water as it struggles to maintain cross‑flow, regardless of how good the membrane is.

Once you know you need a pumped system, look at how serious the vendor is about pre‑filtration and pump protection. Industrial and commercial sources, including Axeon Water Technologies, Cannon Water Technology, and Veolia, treat pre‑filtration as non‑negotiable. They specify sediment and carbon stages and may even include antiscalant dosing or softening ahead of RO. In residential products, WECO and similar brands spell out sediment ratings, carbon types, and maintenance intervals. When a spec sheet clearly shows sediment and carbon before a booster pump or discusses protecting the pump from high solids, that is a sign you are effectively getting a pre‑pump layout or a hybrid that borrows its logic.

Certification is another important indicator. The Water Quality Association recommends looking for NSF or similar standards such as NSF/ANSI 58 for RO drinking water units, which verify performance and durability under defined conditions. Independent lab testing described by Water Filter Guru, where systems like AquaTru and other units were evaluated for contaminant removal, waste ratios, and practical operating behavior, also shows how different designs perform in the real world. Systems that can demonstrate both strong contaminant reduction and good efficiency are generally worth prioritizing over models that only claim “up to ninety‑nine percent removal” without efficiency details.

Finally, pay attention to maintenance friendliness. Axeon suggests six to twelve month pre‑filter checks; WECO provides clear guidance on changing sediment and carbon cartridges and describes how storage tank air charge affects flow. A system that makes filter changes straightforward and provides honest replacement schedules is far more likely to stay efficient for a decade than a unit where cartridges are buried, unlabeled, or tied to a proprietary service plan that encourages neglect.

Brief FAQ

Is a pumped RO system always more efficient than a non‑pumped one?

Not always. On low‑pressure supplies, a booster pump can significantly improve practical efficiency by bringing the membrane up to its design pressure, which improves contaminant rejection, reduces waste ratios, and shortens tank refill times. On higher‑pressure municipal supplies, a well‑designed un‑pumped system with good pre‑filtration and a modern low‑waste membrane can perform very well without the added electrical load and mechanical complexity of a pump.

Can I convert a post‑pump system into a pre‑pump layout myself?

Re‑plumbing pump and filter order is more than just moving hoses. Filter housings have specific pressure ratings, pumps have minimum inlet pressure requirements, and auto shut‑off valves and check valves are oriented for a particular flow path. Articles from Cannon Water Technology, WECO, and the Water Quality Association all emphasize that RO systems, while simple in concept, require some technical knowledge to configure correctly. If you suspect your system would benefit from a different layout, it is safer to work with the original manufacturer or a qualified water treatment professional than to rearrange components on your own.

What matters more than pump placement if I want an efficient RO system?

The largest levers, based on the research notes, are overall pre‑treatment quality, membrane selection, recovery and waste ratio settings, pump sizing and control, and consistent maintenance. Pre‑filters that protect both pump and membrane, membranes that are appropriate for your water’s salinity and fouling tendency, and a pump that operates near its best efficiency point are all higher priorities. Pump placement becomes important mainly as part of that bigger picture: a layout that keeps both pump and membrane clean is easier to keep efficient.

In the end, both pre‑pump and post‑pump RO designs can deliver excellent drinking water. The systems that age gracefully, without turning into noisy, wasteful gadgets under your sink, are the ones that combine robust pre‑filtration, a sensibly controlled pump, and membranes that are matched to your water. If you focus on those fundamentals and choose a system whose design philosophy is transparent and well supported by reputable technical sources, you will get not just cleaner water, but smarter hydration at home for years to come.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverse_osmosis

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/articles/reverse-osmosis-optimization

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9692277/

- https://nmwaterconference.nmwrri.nmsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2011/Relevant-Papers/reverse_osmosis_homer_deep.pdf

- https://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/archive/releases/2021/Q2/breakthrough-in-reverse-osmosis-may-lead-to-most-energy-efficient-seawater-desalination-ever.html

- https://wqa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Article-4-POU-RO-Performance-and-Sizing.pdf

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393003321_Comparative_Analysis_of_the_Efficiency_of_Reverse_Osmosis_and_Hydroxyapatite_for_Fluoride_Removal_in_Water_A_Case_of_AUWSA

- https://atmosfermakina.com/reverse-osmosis-systems-include-a-pump/

- https://www.brotherfiltration.com/why-need-pre-filtration-before-high-pressure-pump/

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/understanding-ro?srsltid=AfmBOoq91FCq2yzQIsc2_9T3tQVRL74mzyw9GgdvEzOR6q-HwV0OE6IV

Share:

Why 304 Stainless Steel Faucets Cost More Than Copper Faucets

Carbon Fiber Filters vs. Traditional Activated Carbon: Which Is Better For Your Home Water?