If you care about both your family’s hydration and your household’s water footprint, you have probably seen bold claims about “1:1 wastewater ratios” in modern reverse osmosis systems. As a smart hydration specialist who spends a lot of time under kitchen sinks and in mechanical rooms, I can tell you this is one of the most misunderstood specifications in home water treatment.

A 1:1 ratio sounds simple and attractive: one gallon of purified water for one gallon of “waste.” The reality is more nuanced. The wastewater ratio ties directly into how the membrane stays clean, how long it lives, how well contaminants are removed, and even how your septic or municipal sewer system behaves downstream.

In this guide, I will walk you through what that 1:1 number really means, how it compares to traditional systems, where it makes sense, and where chasing that number can quietly undermine water quality, system life, or both.

How Reverse Osmosis Works And Why It Produces Wastewater

Reverse osmosis, or RO, is a pressure-driven filtration process. Unlike simple carbon cartridges that strain out larger particles and some chemicals, RO uses a semi‑permeable membrane with incredibly fine pores. Several sources, including technical briefings from RO manufacturers, put those pores in the range of about 0.0001 micron for residential drinking water systems. That is how RO is able to remove many dissolved salts, heavy metals, and microscopic contaminants that ordinary filters leave behind.

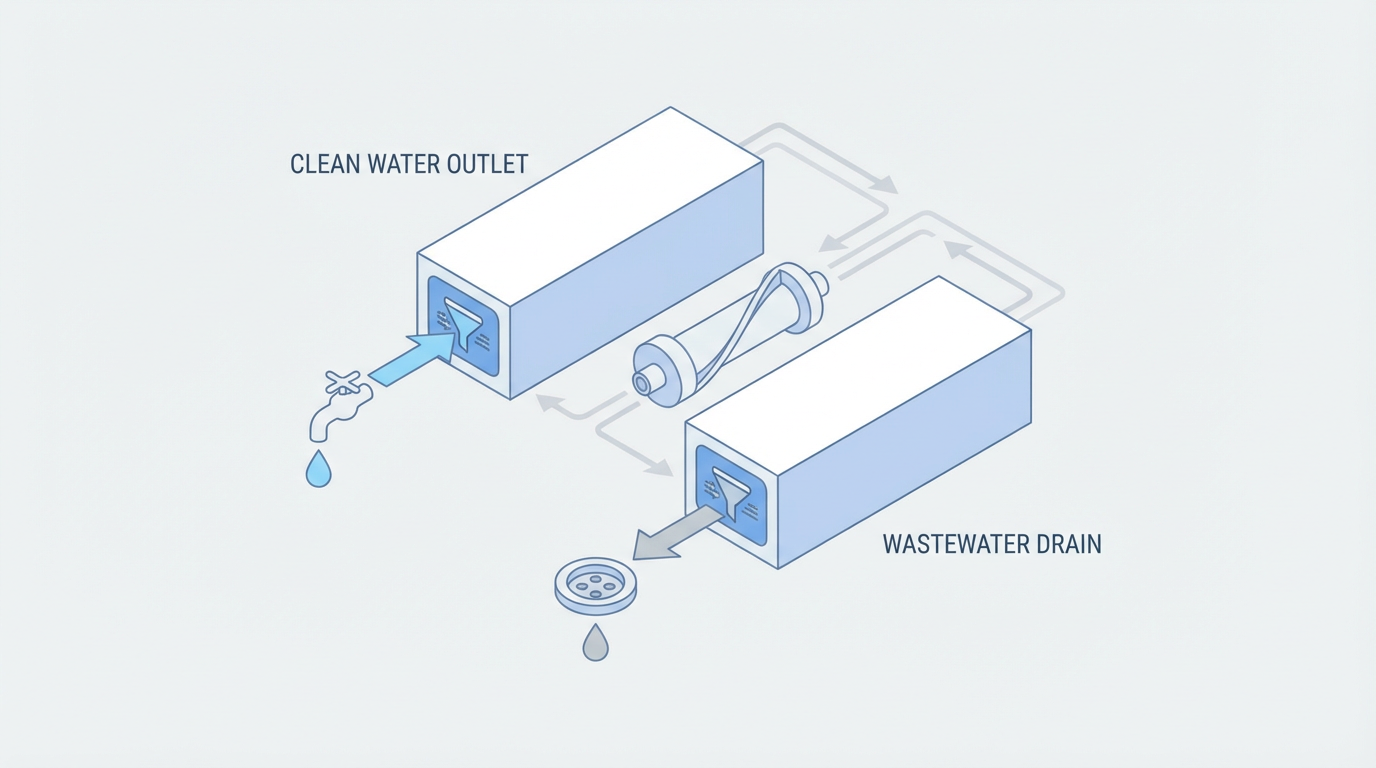

In a typical drinking-water setup, tap water first passes through prefilters such as sediment and activated carbon. These stages catch sand, rust, chlorine, and organic chemicals and protect the membrane from premature fouling. After that, the water enters the RO membrane housing. Inside, pressure forces water molecules through the membrane. This purified stream is called permeate or product water.

The rest of the water does not simply stop at the membrane. It flows along the membrane surface and exits as a more concentrated stream that carries away the rejected contaminants. This second stream is called concentrate, brine, or reject water. Many homeowners know it simply as RO “wastewater.”

From a membrane-health standpoint, that “waste” stream is not optional. If the system tried to convert every drop of feed water into purified water, the dissolved minerals and other contaminants would accumulate on the membrane surface, blocking channels, driving up pressure, and destroying performance. Specialist sources such as Pentair and Pacific Water Technology describe this process as membrane fouling and, under high pressure, compaction. Either way, the result is worse water, higher energy consumption, and shorter membrane life.

So RO wastewater is essentially the flushing mechanism that keeps the membrane’s ultra-fine pores working as intended.

What The Wastewater Ratio Actually Measures

When manufacturers talk about a wastewater ratio, they are comparing how much purified water your system produces to how much water it sends to drain during that same period.

For clarity, in this article I will describe ratios as “purified water : wastewater.” A traditional under‑sink RO system might be described as 1:4, meaning that for every 1 gallon of drinking water you get, about 4 gallons go down the drain. That aligns with multiple sources, including Water Filter Guru and Bluevua’s technical explanations, as well as empirical testing shared by RO vendors.

Researchers and public agencies describe similar behavior in slightly different terms. The University of Minnesota’s onsite wastewater experts note that many point‑of‑use under‑sink RO systems operate at only 10–20 percent recovery. In plain language, that means they may discharge roughly 4–9 gallons of concentrate for every gallon of treated water. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense program reports that common point‑of‑use RO units can reject 5 or more gallons for every gallon of treated water, with inefficient models wasting up to 10 gallons per gallon of permeate.

The absolute numbers sound alarming until you look at how much drinking water a family actually uses. Water Filter Guru illustrates this with a simple example. If a family of four each drinks around half a gallon of RO water per day, that is about 2 gallons of purified water. At a 1:4 ratio, that household would waste roughly 8 gallons per day to produce those 2 gallons of drinking water. For health-centered households using RO only for a dedicated drinking tap and maybe cooking, the total extra usage is modest compared with showers, toilets, outdoor irrigation, and other big water users in the home.

The ratio still matters, especially in drought‑prone regions or on expensive municipal water, but context is important. The real engineering challenge is to reduce that waste without compromising the membrane’s ability to protect you from contaminants.

Real-World Ratios: From Traditional RO To High-Efficiency And 1:1 Claims

A good way to understand a 1:1 claim is to see where it fits on the spectrum of typical RO designs.

Traditional under‑sink RO systems have often operated around a purified: waste ratio of roughly 1:4. Pacific Water Technology, a residential and commercial RO supplier, describes 3–5:1 waste‑to‑pure ratios (which corresponds to about 1:3–1:5 purified: waste), targeting around a 4:1 average to support membrane life of roughly two to three years.

Independent water‑quality educators reinforce that picture. The EPA’s WaterSense program states that conventional point‑of‑use RO systems frequently send 5 or more gallons of reject water down the drain for each gallon of treated water, and in some cases up to 10. The University of Minnesota similarly points to 4–9 gallons of reject water per gallon of permeate for many under‑sink units.

In recent years, more efficient designs have begun to change that math. Several trends appear in the research and product literature:

Modern point‑of‑use systems: Consumer‑focused reviewers like Water Filter Guru note that newer RO systems commonly advertise ratios such as 1:2, 1:1, and even 2:1 purified: wastewater. Some achieve this by reducing how much water leaves the RO chamber during each pass, while others incorporate internal recirculation that sends some concentrate back through the system instead of directly to drain.

Countertop RO units: Design notes from Bluevua describe countertop systems that achieve around a 3:1 ratio (three gallons of purified water to one gallon of wastewater) by mixing some pre‑filtered water with feed water before it hits the membrane. This dilutes the incoming contaminant concentration and reduces mechanical stress, which in turn cuts total wastewater and helps extend membrane life.

Whole‑house RO systems: For whole‑home units, a University of Minnesota overview cites efficiencies in the 50–75 percent range. In practice, that equates to something like 1:1 to 3:1 purified: waste, depending on the design and operating conditions. These systems often use pressurized storage tanks, recirculation, and other controls to manage both water use and performance.

Water‑efficient certified systems: The EPA’s WaterSense specification for point‑of‑use RO, finalized in 2024, sets an upper limit of 2.3 gallons of reject water per gallon of treated water. That means WaterSense‑labeled units must operate at roughly 1:2.3 purified: waste or better while still achieving contaminant reduction requirements and a minimum one‑year membrane life. EPA estimates that replacing a typical point‑of‑use RO with a WaterSense‑labeled model can save a household more than 3,100 gallons of water per year and that national adoption could save more than 3.1 billion gallons annually.

Industrial systems: At the other extreme, Pacific Water Technology notes that industrial RO can reach about a 1:1 waste‑to‑pure ratio (which is 1:1 purified: waste) but only by using more complex designs such as recirculation loops and continuous antiscalant dosing to prevent scaling and fouling.

Within this landscape, a residential under‑sink or countertop system advertised as 1:1 sits at the very aggressive end of water‑saving performance. The key question is how that number is achieved and at what cost to membrane longevity and water quality over time.

The Engineering Reality Behind 1:1 Ratios

To understand why engineers get nervous about ultra‑low wastewater ratios, it helps to picture what is happening on the membrane surface.

The RO membrane is constantly dealing with incoming dissolved solids. When everything is balanced, the brine stream flowing across the membrane carries away those rejected contaminants. The ratio of product to waste is managed by a component called a flow restrictor or regulator on the drain line. This restrictor creates back‑pressure so that some water is forced through the membrane, but enough water still moves past the membrane to flush away concentrated salts and other contaminants.

If you simply tighten up the restrictor or install a smaller one to achieve a prettier ratio on paper, you are demanding a higher “recovery” rate from the same small membrane area. That drives the concentration of dissolved solids on the membrane surface higher. Over time, those concentrated minerals and organics can precipitate, forming scale and fouling layers. Pacific Water Technology describes how this raises pressure drop, reduces water flux, and can lead to irreversible membrane degradation or compaction.

Experienced reef‑aquarium hobbyists, who are among the most demanding RO users, have discussed this in depth. Summaries of forum threads show a consistent concern: if you push a residential membrane from manufacturer‑recommended ratios around 1:3 or 1:4 toward 1:1 without changing the underlying design, you often see faster membrane fouling, higher product‑water total dissolved solids, and much quicker exhaustion of any downstream deionization resin.

Industrial plants do reach very high recoveries and near‑1:1 waste ratios, but they combine several tools that are not usually present in a compact under‑sink system. These include staged membranes with recirculation loops, precise control of cross‑flow velocity, continuous chemical dosing with antiscalants, and frequent monitoring. Commercial whole‑house systems like the Crystal Quest units described in technical literature often include concentrate recycle valves, digital TDS monitors, and advanced controllers. Those options are designed to improve recovery while preserving system health, not just to squeeze down the drain line blindly.

On the residential side, some manufacturers engineer systems that can genuinely operate near 1:1 under certain conditions. Techniques include internal recirculation of concentrate, permeate pumps that recover pressure energy, and carefully matched flow control and membrane sizing. Pentair, for example, notes that its FreshPoint RO platform can reduce water sent to drain by about 50 percent compared with many traditional systems, though it does not specify a universal 1:1 ratio.

The takeaway is that there is a world of difference between a carefully engineered water‑saving RO design and a simple restrictor swap or marketing claim. The former can be a win for both water and health. The latter can quietly erode the very water quality you installed RO for in the first place.

Pros And Cons Of Water-Saving And 1:1 RO Systems

From a smart hydration perspective, any discussion of wastewater ratios has to start with health, then expand to costs and environmental impacts.

On the positive side, a well‑designed water‑saving RO system can significantly reduce the volume of concentrate while still delivering the core benefits of RO. Residential RO systems are widely documented by manufacturers and third‑party guides to reduce many contaminants that matter for long‑term health, including lead, arsenic, nitrates, fluoride, and various dissolved solids. Culligan, Pentair, and similar companies cite broad contaminant reduction ranges, often 90 percent or more for many regulated contaminants when systems are properly certified and maintained.

Using RO at the kitchen sink also lets many households ditch bottled water for daily drinking and cooking. Industry and consumer analyses show that RO water produced at home typically costs far less per gallon than single‑use bottled water, particularly when you factor in the convenience of having clean water on tap. Several articles in your research notes point out that this shift cuts plastic bottle waste dramatically, which is a meaningful environmental win even when RO wastewater is considered.

Water‑saving RO systems offer another environmental benefit: they simply use less water to provide the same volume of drinking water. EPA WaterSense estimates that a single labeled point‑of‑use RO unit can reduce household water use by more than 3,100 gallons per year compared with a typical unit. Scaled nationally, the potential savings reach billions of gallons annually.

The tradeoffs show up in system complexity and maintenance. Pushing toward very low wastewater ratios can make systems more sensitive to feed‑water conditions such as hardness, total dissolved solids, pressure, and temperature. Pacific Water Technology warns explicitly that marketing claims of 1:1 waste‑to‑pure ratios in basic residential units can be misleading and that operating at such low waste can shorten membrane life, effectively benefiting sellers through more frequent membrane replacement sales.

There are also implications for septic and onsite wastewater systems. The University of Minnesota’s guidance for septic professionals notes that typical under‑sink RO units do not usually overload a septic system, even with relatively inefficient ratios, because total drinking‑water volume is small. However, whole‑house RO is another story. Point‑of‑entry systems that treat all the water entering a home can discharge large volumes of concentrate, often at 50–75 percent efficiency. If that reject stream is tied directly into a septic system that was never designed for those flows, it can create hydraulic overloading and salinity issues. Minnesota’s experts therefore recommend carefully evaluating both the volume and salinity of reject water and, in some cases, routing it away from the septic system or using it for irrigation.

For families on municipal sewer, that concentrated wastewater still matters at the community scale. Research you provided on the broader water–carbon and water–stress nexus shows how conservation decisions upstream can change pollutant loads and flows in wastewater treatment plants and receiving waters. While those studies focus on large systems rather than individual homes, the principle remains the same: smarter indoor water use and well‑designed reuse of RO concentrate can support both water security and environmental quality.

How To Read A 1:1 Wastewater Claim Like A Pro

When you see “1:1 wastewater ratio” on a brochure or website, it pays to slow down and ask a few key questions. This is exactly the kind of conversation I have with homeowners at kitchen tables.

First, clarify how the ratio is defined and under what conditions. Is the number based on purified water versus wastewater at a specific pressure, feed‑water temperature, and total dissolved solids level, or is it a generic marketing number? Many membrane performance ratings assume around 77°F feed water, moderate TDS, and at least 40–50 psi. Water Filter Guru points out that low feed‑water pressure increases wastewater, and modern RO units sometimes need a booster pump to achieve their advertised performance in real homes.

Second, look for independent efficiency and performance certifications. The EPA’s WaterSense label for point‑of‑use RO systems is not a 1:1 guarantee, but it does cap reject water at 2.3 gallons per gallon of treated water and requires systems to meet specified contaminant reduction and membrane‑life criteria. A unit that meets this specification has at least been evaluated by an independent laboratory for both efficiency and water quality performance.

Third, ask how the system achieves its ratio. Is there internal recirculation of concentrate, a permeate pump, staged membranes, or other features that manage fouling and scaling? Or did the manufacturer simply choose a small flow restrictor on the waste line? Systems like Bluevua’s countertop units and Pentair’s FreshPoint RO describe specific design features aimed at reducing wastewater while protecting the membrane. That level of detail is a good sign.

Fourth, investigate maintenance expectations. Does the manufacturer still stand behind a multi‑year membrane life when the system operates in a more water‑efficient mode? Pacific Water Technology reminds consumers that overly aggressive waste reduction tends to show up in faster membrane and resin replacements. If the consumable schedule looks unusually frequent for a claimed “high‑efficiency” system, you may be paying for water savings at the parts counter.

Finally, consider your whole plumbing and wastewater picture. If you are on a septic system, Minnesota’s guidance suggests verifying how and where any whole‑house RO unit discharges its reject water and whether there are better options, such as irrigation or a separate subsurface discharge where allowed. Even for under‑sink systems, it can be smart to capture concentrate for non‑potable uses rather than sending it straight to sewer.

Practical Ways To Save Water Without Sacrificing Water Quality

You do not have to choose between excellent drinking water and responsible water use. Several evidence‑backed strategies show up repeatedly across technical and consumer sources.

Choosing a modern, well‑designed system is often the biggest step. As EPA WaterSense and multiple manufacturers highlight, newer point‑of‑use RO units with internal recirculation, efficient membranes, or permeate pumps can cut wastewater dramatically compared with older designs. In many cases, moving from a conventional 1:4 ratio to something closer to 1:2 or a WaterSense‑compliant 1:2.3 offers most of the water savings benefit without the headaches associated with forcing a residential membrane to operate at 1:1 under unfavorable conditions.

Maintaining proper water pressure is another low‑friction win. Water Filter Guru notes that most reverse osmosis systems need at least about 40 psi to run efficiently, and inadequate pressure both slows down production and increases waste. If your home has low pressure, a small booster pump can bring the system into its designed operating window, improving both performance and efficiency.

Regular maintenance is equally important. As filters and membranes clog, flow slows and wastewater usually goes up. Consumer and manufacturer guidance typically recommends changing prefilters and postfilters every six to eighteen months and RO membranes about every two to three years, depending on usage and water quality. Staying on schedule ensures that water has a clear path “from A to B,” as one specialist puts it, which keeps both waste ratios and contaminant removal closer to design values.

Reusing concentrate is one of the smartest lifestyle shifts I see health‑conscious, eco‑minded families adopt. Multiple sources in your research note that RO reject water has already passed through prefiltration stages and mainly contains higher concentrations of dissolved minerals and contaminants than the purified stream, not raw sewage. Bluevua and Water Filter Guru both suggest using this water for tasks like mopping floors, rinsing patios, washing cars, and pre‑rinsing laundry. The University of Minnesota and other water‑stewardship groups point to irrigation as another option, noting that many plants actually appreciate the extra minerals, provided local water chemistry and soil conditions are compatible.

Practically, this can be as simple as directing the RO drain line into a storage container or a separate plumbing line that feeds an outdoor faucet or toilet tank, as long as your local plumbing code allows it.

The key is to ensure that any collection container is secure and that you use the stored water before it overflows or stagnates.

Above all, resist the temptation to “tune” a traditional system to an arbitrary 1:1 ratio by replacing flow restrictors or otherwise tightening the drain without a clear understanding of the consequences. The field experience summarized by Pacific Water Technology and reef‑keeping communities is consistent: when waste is pushed too low on a system not designed for it, the hidden costs show up in membrane performance and replacement frequency.

When Does A 1:1 System Make Sense?

There are situations where a rigorously engineered 1:1 or near‑1:1 system can be a smart choice.

If you live in a region with very high water and sewer costs or under strict drought restrictions, shaving even a few gallons per day off indoor use can matter. Similarly, if your home relies on a limited groundwater source or a community system under stress, efficient point‑of‑use treatment aligns with broader water‑stewardship goals. EPA WaterSense’s national savings estimates underscore how cumulative small changes in device efficiency can add up to meaningful water security benefits.

For many households, however, the question is not whether they can reach a perfect 1:1 ratio but how to balance water conservation with health protection and long‑term reliability. In homes where the primary concern is removing specific contaminants from otherwise safe municipal water, EPA emphasizes that reverse osmosis is not always necessary. Simple cartridge-based filtration often provides adequate protection with negligible wastewater. Organizations like the Environmental Working Group point out that RO shines when you need to reduce multiple contaminant groups at once, which is common for private wells or areas with complex water quality challenges.

If you decide that RO is the right tool for your drinking water, the next step is to weigh system options in context. A WaterSense‑labeled under‑sink system with a ratio around 1:2 may, in practice, deliver a better overall balance of safety, efficiency, and simplicity than a more aggressive 1:1 unit that depends heavily on ideal feed‑water conditions and meticulous maintenance.

From my seat as a water‑wellness advocate, I encourage families to prioritize certified contaminant reduction, realistic efficiency backed by independent testing, and practical strategies to reuse RO concentrate. When those boxes are checked, whether the label says 1:2.3 or 1:1 matters less than how you actually use and care for the system over its lifetime.

Typical RO Wastewater Ratios At A Glance

To pull these threads together, here is a simple comparison based on the sources in your research notes.

System type or reference |

Purified water : wastewater (approximate) |

Notes |

Older under‑sink point‑of‑use RO (various sources) |

1:4 to 1:9 |

Many traditional units waste 4–9 gallons per gallon of permeate, depending on design and conditions. |

Conventional point‑of‑use RO (EPA WaterSense) |

About 1:5 to 1:10 |

EPA notes many existing units send 5 or more gallons, up to 10, to drain per gallon of treated water. |

Typical residential systems (Pacific Water Technology) |

Around 1:3 to 1:5 |

Described as 3–5:1 waste‑to‑pure, supporting membrane life of roughly two to three years. |

Countertop RO with internal recycling (Bluevua) |

About 3:1 |

Roughly three gallons of purified water to one gallon of wastewater due to internal dilution and reuse. |

WaterSense‑labeled point‑of‑use RO (EPA specification) |

At least about 1:2.3 |

Reject water limited to 2.3 gallons per gallon treated, with performance and membrane‑life criteria. |

New “high‑efficiency” residential RO (various) |

Commonly 1:2, sometimes 1:1 or 2:1 |

Achieved with design features like recirculation and pumps; performance depends on real‑world factors. |

Industrial RO with advanced controls (Pacific Water Technology) |

Around 1:1 |

Uses recirculation loops and continuous antiscalant dosing; not directly comparable to simple home RO. |

These ranges are not universal promises; they are grounded in the specific studies and product descriptions in your notes. Actual performance in your home will vary with your water chemistry, temperature, and pressure, as well as how the system is installed and maintained.

Short FAQ

Does a 1:1 RO system mean it is “waste‑free”?

No. A 1:1 ratio still means that for every gallon of purified water you drink, roughly one gallon goes to drain. You are cutting waste compared with a 1:4 system, but you are not eliminating it. The concentrate stream remains essential for flushing contaminants away from the membrane.

Is chasing a 1:1 ratio always a good idea?

Not necessarily. Experts such as Pacific Water Technology and experienced hobby users warn that forcing traditional residential membranes to operate at very low waste ratios can shorten membrane life and degrade water quality. A thoughtfully designed, independently tested efficient system is far preferable to an aggressive ratio achieved by simply restricting the drain.

Will a 1:1 system overload my septic system?

For under‑sink point‑of‑use systems used only for drinking and cooking, the University of Minnesota’s septic specialists note that even traditional, less efficient RO units generally do not overload a septic system. Whole‑house RO is different because it can discharge large volumes of concentrate. If you have a septic system and are considering whole‑home RO or larger water‑treatment upgrades, it is important to consult a wastewater professional about where that reject stream should go.

As you weigh your options, try to keep a balanced view. Your goal is not to win a ratio contest; it is to get reliably clean, great‑tasting water at the tap while respecting your local water resources. With the right system and a few practical habits, you can enjoy both confident hydration and responsible water stewardship at home.

References

- https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=30000DS4.TXT

- https://septic.umn.edu/news/reverse-osmosis

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12162038/

- https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/conservation/regs/docs/task5-wastewater-excerpt.pdf

- https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/reverse-osmosis-water-filters-when-are-they-good-choice

- https://www.ppic.org/blog/unintended-consequences-indoor-water-conservation/

- https://pacificwater.com.au/residential-ro-systems-waste-to-pure-ware-ratio-explained/?srsltid=AfmBOoqoVfMunugYeX4mER9wyKieLWd3mmXItGTEeQ1UVViKY4vpM0Cz

- https://crystalquest.com/products/whole-house-reverse-osmosis-system?srsltid=AfmBOorah8zjDlk9msna-zzp8y0s3Cy0as_QYRM0oret7g6nbglfO862

- https://www.culligan.com/blog/the-benefits-of-having-a-reverse-osmosis-filtration-system-at-home

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/reverse-osmosis-advantages-and-disadvantages?srsltid=AfmBOorgmHJ3t5KjUo-txProM82I0Dfaz7KhUi7ewLdFtccbx8N3JXAi

Share:

Understanding the Importance of pH Range for RO Membrane Functionality

Understanding When and Why to Boost RO Pressure Toward 0.6 MPa (About 87 PSI)