When a reverse osmosis (RO) system suddenly stops producing water, it can feel like your home hydration routine just hit a brick wall. The faucet trickles or runs dry, the tank never seems to refill, and you are left wondering whether the system has quietly died or if something upstream is holding it back.

As a smart hydration specialist, I see the same pattern again and again in real homes: most “dead” RO systems are not truly broken. They are protecting themselves from poor conditions, starved of pressure, or clogged to the point that they cannot do their job. The good news is that once you understand how an RO system is supposed to move water, the reasons it “refuses to operate” become logical and fixable.

In this guide, I will walk you through the science and the real‑world troubleshooting, drawing on field-proven insights from manufacturers and water-quality experts such as Axeon, ESP Water, Crystal Quest, Fresh Water Systems, DuPont, and the University of Nebraska Extension. The goal is simple: help you restore dependable, healthy drinking water without guesswork or unnecessary part swapping.

What “Not Operating” Really Means

When homeowners say an RO system “isn’t working,” they usually mean one of three things. The dedicated RO faucet is only dripping or completely dry. The storage tank never seems to fill, so there is no reserve of filtered water. Or the system is not even sending waste water to the drain, as if the whole unit has gone on strike.

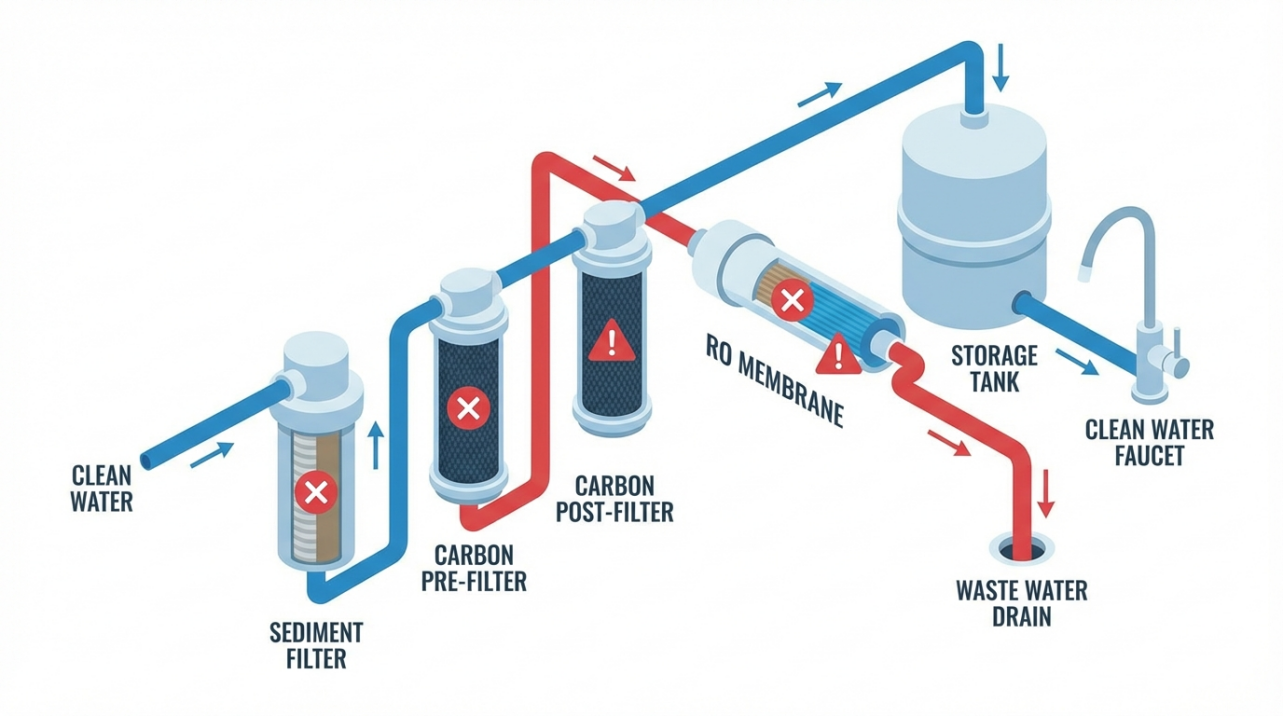

Each of these symptoms points to a break in the chain between the tap, the membrane, and the tank. In a properly operating under-sink system, feed water enters through sediment and carbon pre-filters, passes across the RO membrane under pressure, and then splits into two streams: low-mineral permeate that goes to the tank and higher‑TDS waste that goes to the drain. A check valve and an automatic shutoff valve coordinate this dance so that production stops once the tank is full.

If any piece of that chain fails, the safest response of the system is to produce less water or none at all. That is why ESP Water’s troubleshooting guide emphasizes basic checks such as supply pressure, tank pressure, and valve position before assuming a serious failure. In practice, those simple conditions account for a large share of “mysterious” shutdowns.

How a Healthy RO System Moves Water

To understand why your RO system might refuse to operate, it helps to picture what “healthy” looks like.

The journey from tap to tank

Most residential systems described by University of Nebraska Extension and Culligan follow the same basic path. Incoming tap water enters a sediment filter that screens out rust and grit, then one or more carbon filters that remove chlorine and many organic chemicals. These pre-filters protect the delicate RO membrane, which is a thin, semi‑permeable barrier that rejects most dissolved salts, metals, and many other contaminants.

Pressure from your house line pushes water across the membrane. A portion becomes treated water; the rest carries away the concentrated contaminants as waste. The treated water flows through a check valve into a small pressurized tank, typically in the 2–5 gallon range, and finally through a polishing carbon filter to a dedicated drinking faucet.

In everyday terms, that means your RO system is constantly balancing three things: incoming pressure, membrane resistance, and tank back‑pressure.

When any of those goes out of range, water production drops and eventually stops.

Why pressure and waste water matter

Both Nebraska’s NebGuide on drinking water treatment and industrial guidance from WaterTech and DuPont stress that RO is a pressure‑driven process. It does not “suck” water; it relies on feed pressure that is usually at least about 40 psi at the inlet. At the same time, the system needs an open path for waste water. A tiny component called a flow restrictor creates the correct backpressure across the membrane and ensures enough concentrate flow to carry away scale‑forming minerals.

If incoming pressure falls too low, or if the waste path becomes plugged, the system will effectively stall. In large industrial units, DuPont notes that operators watch feed pressure, flows, and differential pressure closely because changes in concentrate flow are early warning signs of fouling. The same physics apply under your kitchen sink, even if you do not have gauges.

As a simple example, University of Nebraska Extension describes how cold water alone can slow production. Many household membranes are rated at around 77°F. For every degree the feed water drops below that, output typically shrinks by roughly 1–2 percent. If your system is rated to produce 24 gallons per day at 77°F, but your winter well water is closer to 45°F, you might see only about half that output even when everything else is perfect.

That slower production is not a failure, but it often gets mistaken for one.

Reason 1: Feed Water and Pressure Problems

When an RO system refuses to operate, one of the most common root causes is simply that it is not being fed properly.

When the system starves for pressure

Multiple troubleshooting resources from ESP Water, Fresh Water Systems, Ampac, and Ecosoft converge on the same threshold: typical residential RO systems need a minimum of about 40 psi of inlet pressure to run correctly. Below that, production slows dramatically, and at some point the system behaves as if it has stopped.

Here are the typical scenarios professionals see:

The water supply to the RO is actually turned off. ESP Water’s troubleshooting tables bluntly list “water supply turned off” as a top reason for no or slow flow. After servicing, it is easy to forget to reopen the small under-sink shutoff valve feeding the system.

House pressure has dropped. City pressure can sag during high‑demand periods, and some well systems cycle between higher and lower pressures. In a JustAnswer case involving a GE under‑sink RO, the expert’s first test was simple: disconnect the 1/4 inch feed line and see whether you can stop the flow with your thumb. If you can easily pinch it off, pressure is probably marginal for RO.

The storage tank cannot build enough backpressure. An RO tank has an air side and a water side separated by a bladder. Fresh Water Systems and ESP Water both recommend setting tank precharge to about 5–7 psi when the tank is empty. If the tank is under‑pressurized, the membrane sees too little backpressure, and production and delivery can both be affected.

To make this concrete, imagine a small under‑sink system with a 3 gallon tank serving a family that drinks about 1 gallon of RO water per day in total. With house pressure at 60 psi and tank precharge correctly set, the system might comfortably keep up. If a failing well pump drops your feed pressure to around 30 psi, production could fall to less than half of rated output. The tank may never quite fill, your faucet flow will feel weak, and eventually the system may not seem to refill at all between uses.

How to verify pressure without instruments

Ideally, you would check pressure with a simple gauge, but even without one you can learn a lot by working methodically, as described in the GE case. Start with the building’s water: verify that regular faucets have normal pressure. Then follow the RO line step by step, disconnecting a tube, opening the upstream valve briefly, and watching for strong flow. When you reach a point where flow disappears or becomes a weak dribble, you have found the first restriction.

If you discover low pressure at the very inlet of the RO, a booster pump becomes a health‑protective accessory rather than a luxury. Manufacturers such as Ampac and Ecosoft highlight the role of booster pumps in keeping crossflow high enough to reduce fouling and maintain both performance and membrane life.

Reason 2: Clogged Filters, Fouled Membranes, and Blocked Restrictors

If pressure is adequate and the system is still refusing to operate, the next suspect is internal resistance: filters and membranes that are so clogged they act like a closed valve.

When maintenance turns into an invisible shutoff

Across brands, the maintenance guidance is remarkably consistent. Crystal Quest, ESP Water, Affordable Water, Culligan, and Newater all stress that sediment and carbon pre-filters should typically be replaced every 6–12 months, while the membrane often lasts around 2–4 years when pre-filters are maintained on time. Newater bluntly notes that systems that are regularly maintained can last more than 10 years, while neglected units may fail in just 1–2 years.

From a hydraulic point of view, every overdue filter adds resistance. A heavily loaded sediment cartridge slowly throttles flow. An exhausted carbon block can introduce fines and organic fouling. Pearl Water Technologies explains that scaling and fouling on the membrane surface reduce water flow and require higher operating pressures, eventually starving the permeate side.

The result for you at the faucet is the same: production shrinks, filling the tank can take many hours, and eventually the system reaches a point where it produces so little water that it feels “off,” even though components have not literally broken.

Consider an example that reflects what service companies often see. A homeowner installs an RO system and then stretches pre-filter changes to every three years instead of the suggested annual schedule, because “the water still tastes fine.” By year three, the incoming sediment filter is packed with rust and silt, the carbon block is nearing exhaustion, and the membrane has seen years of higher-than-ideal loading. At that point, flow through the system is so restricted that the tank may take a full day to refill, and a small change in seasonal water temperature or house pressure pushes production effectively to zero.

Flow restrictors and “low waste” flow

The waste side of the RO system can also shut things down. The flow restrictor on the drain line is designed to maintain the right balance between permeate and concentrate. Notes synthesized from Complete Water’s low‑waste troubleshooting explain that a “low waste” or “low concentrate” condition signals restrictions, fouling, or mis-set valves that can damage membranes and degrade performance.

In an under‑sink system, that same phenomenon shows up as a very weak or absent drain flow. If the restrictor or the small screen ahead of it plugs, the membrane sees too little crossflow. Concentrated salts and hardness minerals accumulate along the membrane surface, scaling it and further reducing permeability. Over time, this can bring production nearly to a halt.

JustAnswer’s GE case describes a simple but easily overlooked step: there was a tiny screen and flow control device on the black line coming from the membrane. The expert noted that this should be cleaned or replaced whenever the membrane is changed. When that component is completely blocked, the system stops sending water to the drain and cannot maintain normal operation.

Industrial operators are trained to treat low concentrate flow as an alarm. They compare actual waste flow to design values and act quickly to clean membranes and remove obstructions. The same mindset pays off at home: if you notice that the RO drain line is strangely silent, that is a reason to investigate before the membrane is permanently damaged.

Reason 3: Storage Tank, Bladder, and Shutoff Valve Issues

Sometimes the RO system is producing water perfectly well but cannot decide whether to keep running. In those cases, the problem often lives in the storage tank or the automatic shutoff system.

When the tank is full, empty, or confused

The pressurized tank is the small “battery” that lets your RO deliver water quickly even though production is slow. According to ESP Water and Fresh Water Systems, the tank should be pre‑charged to around 5–7 psi with no water in it. Too little air and you get high capacity but weak delivery; too much air and the tank holds very little water before reaching shutoff pressure.

Service guides describe a simple real‑world check. Close the feed water and open the RO faucet to empty the tank. Once no more water comes out, use a standard tire gauge on the tank’s air valve. If you measure essentially zero pressure, or if water spurts from the valve, the internal bladder is likely ruptured. At that point, US Water Systems recommends replacing the tank rather than just adding air, because the bladder failure is the root cause.

From the user’s perspective, a failed bladder can look like a system that refuses to operate. The tank feels heavy, but only a small amount of water comes from the faucet. The RO unit may also run for very long periods because the control valve “thinks” the tank is still not full enough to signal shutoff.

Automatic shutoff valves that say “no”

The automatic shutoff valve (often abbreviated ASO) is a small four‑port device that senses when tank pressure reaches roughly two‑thirds of the inlet pressure and then stops feed water to the membrane. When it fails, the RO system either never stops or never really starts.

Fresh Water Systems explains that if water is constantly running to the drain, the ASO may be stuck open or the check valve may be leaking, preventing pressure from building. On the other side, in the GE troubleshooting case, the auto shutoff valve was effectively stuck closed. Water entered the valve but did not appear at the membrane inlet, so the system behaved as if the feed was turned off even though the supply valve was open.

The diagnostic trick used there is worth repeating. The expert simply bypassed the automatic shutoff: they temporarily connected the pre-filter outlet directly to the membrane inlet. As soon as they did that, the membrane began producing permeate and waste water again. That proved that the membrane and upstream pressure were fine and that the new ASO valve (installed during maintenance) was either mis-plumbed or defective.

In practice, if you have normal pressure at the RO inlet, a tank that is not over‑pressurized, and no water reaching the membrane housing, the ASO or associated check valve becomes a prime suspect. At that point, many homeowners wisely involve a professional, because mis‑wiring those four lines can lead to both non‑operation and leaks.

Reason 4: Installation Errors After Filter Changes

One of the paradoxes of RO ownership is that problems often start right after “doing the right thing” and changing filters. That is because a handful of small installation mistakes can behave exactly like a system failure.

US Water Systems, which fields troubleshooting calls daily, highlights several recurring errors:

Lines reconnected to the wrong ports. With multiple small tubes under a sink, it is surprisingly easy to misroute a line. US Water recommends taking photos before disconnecting anything so that you can restore each connection exactly. Misrouted lines commonly lead to no water production or to water bypassing key stages.

Membranes not fully seated. Standard residential membranes have two o‑rings at the end that must seat firmly into the housing port. If you do not push the membrane in far enough, or if the o-rings are dry, water can bypass or never reach the selective layer. US Water suggests lubricating o-rings with a thin layer of silicone (never petroleum jelly, which can damage rubber) and even using a coin to press the membrane fully into place.

Filter wrappers left on. It sounds almost too obvious, but both US Water and service teams at other companies report cases where a carbon filter was installed with its plastic packaging still on. From the system’s perspective, that is equivalent to installing a solid plug. No water moves, and the RO “refuses” to operate.

Auto shutoff valves installed backward. Many ASO valves are symmetric enough that it is possible to swap the inlet and outlet sides. When that happens, the diaphragm may never open, or it may close prematurely.

These are not exotic failures; they are normal human slips. But because they create a total block or misdirect water, the symptoms can be identical to a bad membrane or failed pump. Whenever an RO system stops working right after a filter or membrane change, it is worth retracing every connection before buying more parts.

Health and Water-Quality Implications When Your RO Is Down

From a wellness standpoint, the most important question is not merely, “Why did my RO stop?” but also, “What am I drinking in the meantime?”

Guidance from the University of Nebraska Extension is clear on one key point: RO is excellent at reducing many dissolved contaminants, including nitrate, metals, and various organics, but it is not designed to be your only microbiological barrier. Membrane defects, bypass leaks, or deterioration can let microorganisms through. That is why many manufacturers emphasize system sanitization at least once a year and draining the system if it sits unused for more than about five days, as noted in ESP Water’s materials and Ampac’s troubleshooting advice.

When an RO system is not operating, there are two main risks.

If plumbing has been altered or mis-installed, you may unintentionally be drinking water that bypasses part or all of the filtration train. For example, installing a new ASO and reconnecting lines incorrectly could route unfiltered water to the faucet. Taste is not a reliable guide here; ESP Water reports that reduced salt rejection can coexist with acceptable flavor until TDS rejection drops below about 80 percent.

If the system stands idle but remains full of water, particularly in a warm kitchen cabinet, it can become a stagnant environment. Ampac and Newater both recommend draining systems that will sit unused for more than several days and performing regular sanitization to control biofouling. In practical terms, if you return from a long vacation, it is wise to empty the RO tank completely and let the system produce a fresh batch before resuming normal use.

On the positive side, many high‑quality RO systems incorporate post‑treatment that improves taste and overall experience. Some manufacturers, such as A. O. Smith, add remineralization stages to restore calcium and magnesium to RO water, addressing concerns about long‑term consumption of very low‑mineral water. Purely from a hydration perspective, if you rely heavily on RO water, planning for system downtime (for example, keeping a small reserve of bottled water or a secondary filter pitcher) ensures you maintain good drinking habits even when your under‑sink system is being serviced.

A Practical Troubleshooting Roadmap for Homeowners

Bringing all of this together, you can approach a “non‑operating” RO system in a structured way, even without professional tools. The idea is not to turn you into a technician, but to help you make smart decisions about what to try yourself and when to call for help.

First, verify the basics. Confirm that the main cold-water valve and the small feed valve to the RO are open, and compare pressure at a regular faucet to what you are used to. If the whole house seems low, your RO is acting as an early warning system for a broader pressure issue. If only the RO is affected, suspect its inlet, pre-filters, or control valves.

Next, check the storage tank. With the feed water on, lightly lift the tank; it should feel noticeably heavier when full than when empty. If the RO faucet has almost no flow even when the tank feels heavy, or if water or zero pressure appears at the tank’s air valve, you are likely dealing with a bladder issue that calls for a replacement tank rather than repeated re-pressurizing.

Then, consider maintenance history. If pre-filters have not been changed in more than a year, or if the membrane is several years old, clogging and fouling become the most probable reasons performance has declined. Crystal Quest notes that with good maintenance, systems can last 15–20 years, while neglected units may last only 5–10 years; the difference is largely in how often filters are changed and systems are cleaned. As a rule of thumb drawn from ESP Water, Affordable Water, and Culligan, most residential RO owners do well with pre-filter changes every 6–12 months, annual sanitization, and membrane replacement every 2–4 years depending on water quality and usage.

Finally, think about what changed just before the problem. If your system stopped working immediately after filter or membrane replacement, trace every connection. Make sure all plastic wrapping was removed from cartridges, that the membrane is fully seated and oriented correctly, and that the automatic shutoff valve is plumbed according to the manufacturer’s diagram. In many of the cases documented by US Water Systems and JustAnswer experts, correcting a mis-routed line or reseating a membrane brought a “dead” RO back to life without any new parts.

To give you a quick reference, here is a concise summary of common symptoms and likely causes based on guidance from ESP Water, Fresh Water Systems, Ampac, and Ecosoft.

Symptom at the faucet or drain |

Likely internal cause |

Simple check you can safely try |

No water or a slow drip from the RO faucet |

Supply valve closed, house pressure low, severely clogged pre-filters, or fouled membrane |

Confirm valves are open, compare pressure at a regular cold tap, and review how long it has been since filters were changed |

Tank never seems to fill, RO runs constantly to the drain |

Low inlet pressure, leaking check valve, stuck ASO valve, or tank that never builds pressure |

Lightly lift the tank to gauge fullness, listen for continuous drain flow, and consider checking tank precharge with the system empty |

Heavy tank but almost no water at the faucet |

Failed tank bladder or incorrect precharge |

With feed off and tank empty, measure pressure at the air valve; water at that valve or zero pressure strongly suggests a failed bladder |

No waste water at the drain line during production |

Blocked flow restrictor, misaligned drain clamp, or clogged small screen on concentrate line |

Observe the drain tube while the system is supposedly running; if it is silent, a service tech may need to inspect the restrictor or screen |

System stops working right after a filter change |

Misrouted tubing, membrane not fully seated, or filter left in plastic wrapping |

Compare tubing connections to the system diagram or photos, gently reseat the membrane with lubricated o-rings, and double-check cartridges |

The most important safety rule is simple: if you are unsure, or if you see signs of significant leaks, electrical components, or complex add‑ons such as permeate pumps, it is perfectly appropriate to call a professional. Companies like Culligan, Newater, and many local dealers offer maintenance plans that include sanitization, pressure checks, TDS testing, and flow verification. For many households, that partnership is the most reliable way to keep water both clean and continuous.

FAQ: Common Questions About “Dead” RO Systems

Why does my RO system stop producing water in winter but seem fine in summer?

Two factors combine in colder months. First, incoming water temperature drops. Nebraska Extension notes that RO production can fall by about half when feed water is around 45°F compared with 77°F. Second, feed pressure can sag when municipal demand is high or when a well system is working harder. Together, those effects may push your system below the effective operating window even though nothing has broken. If performance only collapses during cold weather, a booster pump and timely filter changes often restore reliable output.

Is it safe to drink from an RO system that has been idle for weeks?

Most manufacturers advise against relying on stagnant RO water. Ampac and ESP Water both recommend draining systems that sit unused for more than about five days and sanitizing on a regular schedule. If your system has been idle for weeks, the safest approach is to close the feed, open the RO faucet to empty the tank completely, and then let the system refill and flush before using it as your primary drinking source again. If the system has not been sanitized in a year or more, consider having that done before resuming heavy use.

When should I stop DIY troubleshooting and call a professional?

DIY checks make sense when you are verifying basic things like valve positions, recent maintenance, and visible leaks, or when you are simply replacing pre-filters on schedule. It is wise to involve a professional when you see recurring leaks around housings or fittings, repeated failures of automatic shutoff valves, unexplained swings in TDS despite new filters, persistent low output even with good pressure, or any signs of electrical pumps and controls you are not comfortable working around. As DuPont notes in its industrial maintenance guidance, early expert intervention usually costs less than recovering from full system failure later.

When your RO system “refuses to operate,” it is not being stubborn; it is telling you that something in its environment has slipped out of balance. By understanding how pressure, filtration, waste flow, and storage all work together, you can respond calmly, protect your water quality, and keep your hydration routine resilient. Thoughtful maintenance and smart troubleshooting are some of the simplest, most powerful habits you can adopt for a healthier, better‑hydrated home.

References

- https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/html/g1490/build/g1490.htm

- https://www.affordablewaterinc.com/reverse-osmosis-maintenance-tips-for-first-time-owners

- https://www.watertechusa.com/reverse-osmosis-troubleshooting

- https://www.aquasana.com/info/3-tips-for-maintaining-a-home-reverse-osmosis-system-pd.html?srsltid=AfmBOoq5cwsCs9SKzZZcwPoQG_3biA3nmZCHVWYCe6mEuxYzMcKzcwDU

- https://www.aosmith.com.ph/blog/disadvantages-reverse-osmosis-and-how-we-address-them

- https://complete-water.com/video/reverse-osmosis-troubleshooting-low-waste-flow-low-concentrate-flow

- https://www.culligan.com/blog/how-to-keep-your-water-filtration-system-working-properly

- https://www.dupont.com/knowledge/importance-of-industrial-ro-system-maintenance.html

- https://www.ecosoft.com/post/most-common-problems-with-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/reverse-osmosis-maintenance?srsltid=AfmBOoqRVfbHTxzL1CsMoEMLGcrH9scK9Jk-o1qfU5cHnoJ8nv9wgY1c

Share:

Identifying Wear in Pressure Pump Bearings for Optimal Performance

Understanding Why Your Pump Starts But Lacks Pressure