As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time in older neighborhoods where people are doing all the right things for their health—installing reverse osmosis (RO) drinking water systems—but still struggling with slow, inconsistent, or noisy RO flow. The common thread is aging infrastructure and unstable water pressure. The good news is that with the right strategy, you can stabilize RO performance even in very old districts and protect both water quality and system life.

This article walks through science-backed, practical approaches that I use in the field to diagnose and fix RO output problems where pressure rises and falls throughout the day.

Why Old Districts Are Tough on RO Systems

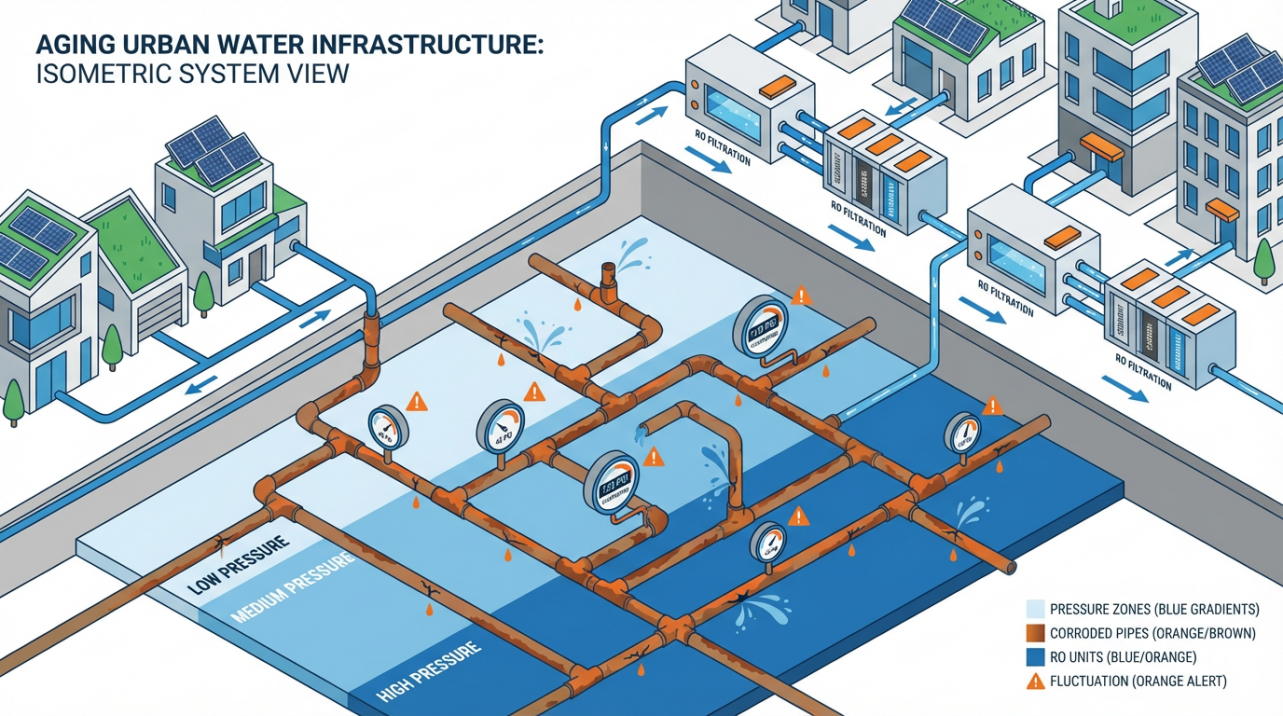

Older districts often sit on top of decades-old mains, patchwork repairs, and plumbing that has seen several generations of tenants and renovations. Utilities and water professionals consistently see a few recurring patterns in these areas.

Aging municipal infrastructure allows leaks, clogs, and mineral buildup to develop in buried distribution pipes and service lines. Hard water minerals such as calcium and magnesium, along with iron and manganese, gradually coat the inside of pipes, narrowing the effective diameter and restricting flow. That restriction shows up at the tap as chronic low pressure, intermittent bursts, or sudden drops in flow.

Utilities may also be managing increased demand from population growth, regional supply sharing, and heavy summer irrigation. According to field experience reported by regional water specialists in the Midwest, seasonal peaks and pump or valve adjustments can create pressure waves that feel random to homeowners but are driven by upstream operations.

Within the building, older plumbing compounds the problem. Leaks in joints or fittings divert water before it reaches fixtures. Corroded or partially blocked pipes further reduce available pressure. Simple clues like a water meter that spins when no water is being used strongly suggest hidden leaks that quietly bleed both pressure and money.

All of this matters because RO systems are pressure-driven.

When supply pressure is unstable in an old district, RO performance becomes unstable too.

How Pressure Instability Damages RO Performance

Reverse osmosis forces water through a semi-permeable membrane. The membrane rejects most dissolved salts, organics, and microorganisms, while purified permeate is stored in a pressurized tank. For this process to work properly, the RO needs adequate and relatively steady inlet pressure.

Evidence from several RO manufacturers and water treatment companies aligns on a few key points:

When pressure is too low, RO systems produce purified water very slowly. Many residential units are designed around feed pressures roughly in the 40–60 psi range, with broader RO guidance often citing about 45–80 psi as typical incoming pressure for homes and small commercial buildings. Below about 40 psi, flow through the membrane drops sharply. You see this as a weak RO tap, long waiting times to fill a glass, and a storage tank that never seems full.

Low pressure also worsens efficiency. Slow permeate production means more water goes to drain per gallon of purified water, which raises your wastewater ratio. Several articles on residential RO note that low pressure can even accelerate fouling of prefilters and membranes, because borderline flow conditions promote deposition rather than efficient sweeping of particles across the membrane surface.

When pressure is too high, different risks appear. Excessive pressure can strain housings, fittings, and the membrane itself. Industry guidance from RO equipment suppliers warns that very high inlet pressure can cause leaks, membrane damage, or premature failure of components that were never designed for that level of mechanical stress. That is one reason many specialists recommend installing a pressure regulator where street pressure repeatedly approaches the high end of the typical residential range, sometimes around 80 psi.

Fluctuating pressure combines the worst of both worlds. Sudden pressure spikes and drops—especially in short pipe runs to under-sink systems—create water hammer and backpressure events. Technical notes aimed at engineers emphasize that short piping does not eliminate water hammer; it simply compresses the pressure wave into a brief but intense spike. That spike can damage RO membranes, telescoping them or stressing o-rings, and it can force feed water to leak into permeate channels, degrading water quality.

In practice, I see three main symptoms in old districts with unstable pressure: slow RO output at some times of day, noisy or “chattering” RO piping, and performance changes over weeks or months that do not match filter-change intervals. All three point back to pressure and flow conditions that the RO was never designed for.

Health and Water Quality Risks Hidden Behind Low Pressure

Stabilizing RO flow is not only about convenience. It is also about safety.

The Environmental Protection Agency has highlighted how low-pressure conditions in municipal or shared systems increase the risk of contaminant intrusion. When pressure in a main or service line drops, contaminated water from surrounding soil or cross-connections can be driven into the pipe through leaks or backflow. Aging districts with old mains and mixed plumbing are particularly vulnerable.

On the distribution system scale, researchers and utilities have shown that high “water age” in storage tanks and nearby pipes can lead to very low disinfectant residual. Case studies using hydraulic modeling found zones near water towers with elevated water age and chlorine levels barely above regulatory minimums. The longer water sits stagnant, the more disinfectant decays and the more disinfection by-products can form.

For your RO system, these upstream dynamics mean that feed water quality and biological load may vary more than you think. In low-pressure, high-age districts, your RO is often asked to do more work against a background of higher microbial and chemical stress. If the RO itself is not operating at its ideal pressure, its barrier function and rejection rates may fall short of what you expect.

That is why pressure stabilization and monitoring are not just equipment issues; they are part of a broader water wellness strategy in older neighborhoods.

Step One: Diagnose Building vs. Municipal Pressure Problems

When I am called to an older home or small business with RO output problems, I start with a structured diagnosis that separates building issues from municipal conditions, using simple tools before recommending any hardware.

First, I verify straightforward plumbing issues. Exposed piping is checked for damp spots, corrosion, or obvious leaks. Faucet aerators and showerheads are removed, cleaned, or replaced to clear debris and scale that can give a false impression of low system pressure. This matches basic troubleshooting guidance promoted by regional water treatment companies: always rule out end-point restrictions before blaming the main system.

Next, I measure static and dynamic pressure with a simple gauge attached to a hose bib or compatible tap. The goal is to see both baseline pressure and how it behaves when fixtures are opened. In stable, well-designed systems, pressure stays within a moderate band while multiple fixtures run. In older districts with infrastructure issues, the gauge often shows notable drops and recoveries as neighbors use water or as utility pumps cycle.

Patterns over the day matter. Several guidance documents on RO performance highlight the impact of peak usage periods. Morning and evening peaks can temporarily drop pressure far below average, explaining why an RO tap feels fine at 11:00 PM but frustratingly slow at 7:30 AM. If I suspect this, I ask residents to record approximate times when RO output feels worst and best, then correlate that with simple pressure checks.

Finally, I consider signs of municipal aging and water age problems. Discolored water, frequent main break notices, or reports of low pressure during firefighting events all point toward broader distribution issues. Studies on water towers and storage tanks show that when tanks see little turnover—often because pumps run constantly to maintain downstream pressure—water age in the tower and surrounding pipes increases. Pressure may look acceptable at times, yet water quality near the end-users is subtly compromised.

If building-side tests show reasonably stable pressure while neighbors also report issues, I know we are dealing mainly with a municipal challenge and must design the RO and its supporting equipment to be more self-reliant. If pressure is unstable inside but not outside the building, the focus shifts to internal plumbing and boosting strategies.

Stabilizing Pressure at the Building Level

Once the source of pressure instability is better understood, the next move is to stabilize pressure before it reaches the RO system. This is where smart pressure management hardware earns its keep.

In buildings with chronically low or fluctuating pressure, a booster pump dedicated to the domestic water supply or to the RO system itself is often the most effective solution. Industry guidance suggests that residential and light-commercial RO systems work best when feed pressure is brought into a roughly mid-range band, avoiding both extremes. Where municipal pressure regularly drops below about 40 psi at peak times, a properly sized booster pump can lift and stabilize feed pressure so the RO sees a consistent environment.

Older multi-story buildings may also benefit from pressure zoning. Utility and hydrant manufacturers describe how segmenting a distribution system into pressure zones and using regulators allows tailored pressure levels for different areas. In a small building, the equivalent is a mix of pressure-reducing valves and booster sets, arranged so that upper floors receive adequate pressure without overwhelming lower floors.

Pressure management is not only about adding pressure. In some old districts, especially near pump stations or after line replacements, static pressure at night can climb above what fixtures and small RO systems are designed to handle. Pressure-reducing valves at the building entry, or ahead of sensitive devices, tame those peaks. Companies specializing in pressure management emphasize that both overly high and overly low pressure can contribute to pipe bursts and leaks, so the goal is a controlled, moderate band.

Another critical issue in older piping is water hammer and backpressure. Experience from industrial RO troubleshooting shows that hard-starting pumps and abrupt valve closures can send pressure shocks through membrane housings, damaging elements and seals. Installing soft-start controls or variable-frequency drives on pumps, and using properly oriented check valves and, where appropriate, small expansion tanks downstream of pumps, helps absorb these transients. In smaller RO setups, adding a compact expansion tank and a check valve right after the booster pump has been used by aquarists and homeowners to reduce both noise and pressure spikes.

The combination of booster pumps, pressure-reducing valves, accumulators, and check valves transforms a jittery old-district pressure profile into something your RO system can rely on.

Hardening the RO System Against Fluctuations

Even with better building-level control, your RO system should be tuned for robustness in a challenging pressure environment. Manufacturers and water treatment experts converge on several best practices.

Correct system sizing comes first. The Water Quality Association and multiple industry sources stress that RO systems must be sized to meet peak household or facility demand without starving pressure. Undersized systems in homes with multiple bathrooms or high simultaneous use will tend to run at extremes, leading to poor flow and rapid wear. When I design or reconfigure ROs for old districts, I often specify slightly larger membrane capacity and storage volume than the bare minimum, so the system can recharge during off-peak times when municipal pressure is better.

Filter and membrane maintenance is the next key. Several residential RO guides recommend changing sediment and carbon prefilters every six to twelve months, depending on water quality and usage, and replacing membranes roughly every two to three years under normal conditions. In older districts with more sediment and variable quality, I treat those intervals as upper limits. Fouled prefilters and membranes increase differential pressure, forcing the system to work harder for every gallon of permeate, and magnifying the effect of any external pressure drop.

The RO storage tank is a frequent hidden culprit. Internal air pressure in the tank’s bladder must be set correctly when the tank is empty—usually around the high single digits in psi, based on manufacturer specs. Field troubleshooting guides describe the classic symptom of an under-pressurized tank: strong initial RO flow that quickly drops to a trickle as the tank cannot push water out effectively. Verifying and resetting tank pressure, or replacing aging tanks that no longer hold a charge, often restores steady flow even when municipal pressure is imperfect.

Flow restrictors and drain-line components deserve attention too. The restrictor maintains the proper backpressure across the membrane and sets the waste-to-product water ratio. If it is clogged or incorrectly sized, product water can be choked off or excessive water can go to drain. Several troubleshooting articles suggest simply testing suspect restrictors by blowing through them and replacing any that feel blocked or worn. On the faucet side, cleaning aerators and inspecting cartridges for mineral buildup helps ensure the final step does not undo upstream improvements.

Finally, pumps and controls on larger RO skids should be selected and configured with pressure stability in mind. Technical guidance from pump manufacturers and energy agencies highlights the value of high-efficiency pumps paired with variable-frequency drives. Matching pump output to actual demand reduces pressure oscillations, cuts energy use, and extends equipment life. For high-pressure systems, energy-recovery devices offer further savings and smoother operation, although these are more common in brackish or seawater RO than in under-sink units.

Monitoring: Turning Guesswork into Data

Pressure and RO performance cannot be stabilized purely by feel in older districts; they need to be monitored.

On the pressure side, utilities and hydrant manufacturers describe a toolkit that ranges from simple gauges to remote telemetry. At the building scale, fixed gauges at the main entry, before and after pressure-reducing valves, and at the RO feed line provide immediate visual feedback. For more complex sites, compact data loggers can record pressure over days or weeks, revealing patterns that eyes and ears miss. Remote monitoring stations, including hydrant-mounted units with wireless communication, are now used by utilities to detect low and high pressure events in real time.

Within the RO system, best-practice guidance from industrial water treatment companies is very clear: log key parameters and trend them over time. At minimum, that means feed, concentrate, and permeate pressures; corresponding flow rates; feed and permeate conductivity; and feed temperature. Those measurements allow calculation of recovery, salt rejection percentage, differential pressure, and normalized permeate flow.

Salt rejection tells you how effectively membranes are removing dissolved contaminants. Healthy RO membranes often deliver rejection rates in the mid to high nineties in percent. Significant declines suggest either membrane wear, mechanical damage, or chemical attack.

Differential pressure across the membrane array is a sensitive indicator of fouling and scaling. When membranes begin to plug with particulate fouling or mineral scale, pressure drop increases. Experts recommend comparing differential pressure stage by stage: rising pressure at the front of the train often points to fouling, while rising pressure toward the end of the train is more characteristic of scaling.

Normalized permeate flow is particularly valuable in fluctuating environments because it corrects for changes in feed pressure, temperature, and conductivity. Membrane manufacturers provide temperature correction tools so operators can distinguish between seasonal variations and true performance decline. In long-term trending, a gradual drop in normalized flow signals increased resistance from fouling or scaling, while an unexplained increase can point to membrane damage or o-ring failures that let water bypass the intended path.

For larger facilities in older districts, integrating these signals into a simple dashboard or SCADA system allows staff to set alarms on critical thresholds—similar to how utilities monitor their own networks. This kind of “smart hydration” approach transforms RO maintenance from reactive filter changing into proactive performance management.

A Practical Stabilization Roadmap for Older Neighborhoods

To make this concrete, imagine a mid-century apartment building in an old district where residents complain that the shared RO drinking station on each floor runs fast in the late evening and painfully slowly at breakfast.

The first step is a basic inspection and measurement. Building staff or a consultant checks exposed plumbing for leaks, cleans aerators, and verifies that building entry pressure during off-peak hours sits within a reasonable band. A simple pressure log over several days then shows that pressure at the RO feed line sags substantially in the early morning and early evening.

At the building mechanical room, a modest booster set is installed or upgraded, sized using actual flow data rather than guesswork. A pressure-reducing valve is set to maintain a stable target pressure entering the RO branch. An expansion tank and check valve are added downstream of the booster pump to smooth pressure transients and protect the RO systems from rapid changes when pumps cycle.

On each RO station, prefilters that have exceeded their maintenance interval are replaced, storage tanks are checked and re-pressurized to the manufacturer’s specification, and any restricted flow restrictors or faucet components are swapped out. A small digital gauge is added to the RO feed line on one representative floor, along with a conductivity meter on the permeate line, to track how well membranes are performing over time.

Over the next few weeks, pressure and performance data are trended. If normalized permeate flow remains stable and residents report that flow feels consistent across the day, the combined strategy has succeeded. If data show continuing dips tied to extreme municipal events, further zoning or an additional local booster at the RO level can be considered.

The same approach scales down to a single-family home and up to a small campus: diagnose, stabilize pressure before the RO, harden the RO system itself, and use monitoring to confirm success.

Quick Comparison of Common Symptoms and Targeted Actions

A concise way to see how these strategies fit together is to compare typical field symptoms with likely underlying causes and appropriate actions.

Symptom in an old district RO setup |

Likely underlying issue (from research) |

Targeted stabilization or fix |

RO faucet starts strong then quickly drops to a trickle |

Under-pressurized or failing RO storage tank bladder; possible low feed pressure |

Verify and reset empty-tank air charge; replace tank if needed; consider a small booster pump if feed pressure is chronically low |

RO flow is always slow, tank never feels “full” |

Feed pressure often below the 40 psi neighborhood; clogged prefilters or fouled membrane |

Measure inlet pressure with a gauge; add or adjust a booster pump; replace overdue prefilters; evaluate membrane condition |

RO system becomes noisy, with rattling or banging sounds |

Water hammer and rapid pressure changes; lack of expansion volume or check valves |

Add an expansion tank and appropriately oriented check valve after the pump; consider soft-start controls or variable-speed pumping |

RO permeate quality declines while pressure drop rises |

Fouling or scaling in membrane elements, often aggravated by unstable hydraulics |

Improve pretreatment; adjust recovery to respect scaling limits; schedule cleaning when normalized flow or differential pressure changes by 10–15 percent |

Whole-building pressure swings widely throughout the day |

Aging municipal mains, insufficient or poorly controlled booster sets, failing accumulators or valves |

Use logging to characterize pressure; repair or resize booster sets; service or replace accumulators and pressure-reducing valves; coordinate with the utility where needed |

The table reflects patterns consistently described by water treatment firms, pump specialists, and pressure-management experts working across aging infrastructure.

FAQ: Living With RO in an Old District

How do I know if I need a booster pump for my RO system?

If a simple pressure gauge at a nearby tap regularly shows incoming pressure dipping below roughly the low forties in psi while you are using water, you are a strong candidate for a booster pump. RO suppliers and independent water specialists repeatedly point out that poor flow, long tank refill times, and a high waste-to-product water ratio are all classic signs of insufficient pressure.

Can very high pressure be “fixed” just by installing a larger RO system?

Oversizing the RO without controlling pressure is not a safe solution. Very high street or building pressure can over-stress the RO housings, fittings, and membrane, leading to leaks and failures. Pressure-reducing valves and proper pressure zoning should be used to bring incoming pressure into a safe band before it reaches the RO, even if the RO has ample capacity.

If my municipal water quality is good, do I still need to worry about water age and low pressure?

Even in regions with high-quality source water, aging distribution systems can create local issues. Studies using hydraulic modeling and field sampling have shown areas near storage tanks or at network edges where high water age leads to low disinfectant residuals and increased risk of contamination during low-pressure events. RO systems add an extra barrier, but they function best when upstream pressure and quality are well-managed, especially in older neighborhoods.

Healthy hydration at home is not just about the filter you install; it is about the pressure profile and infrastructure that feed that filter every hour of the day. In older districts with fluctuating pressure, the path to stable RO output runs through smart pressure management, disciplined maintenance, and simple but consistent monitoring. With those pieces in place, your RO system can deliver the clear, reliable drinking water your household deserves, even on the oldest street in town.

References

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/articles/reverse-osmosis-optimization

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11880092/

- https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/195247/azu_etd_10639_sip1_m.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- https://water-ca.org/wp-content/uploads/3.-Assessing-water-quality-in-a-distribution-network-based-on-hydraulic-conditions.pdf

- https://aquatekwater.net/understanding-water-pressure-fluctuations/

- https://www.watertechusa.com/reverse-osmosis-troubleshooting

- https://blog.dhigroup.com/how-to-improve-water-quality-in-water-distribution-systems/

- https://eaiwater.com/water-quality-monitoring/

- https://www.ecosoft.com/post/most-common-problems-with-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/why-reverse-osmosis-water-flow-is-slow?srsltid=AfmBOoqVGH_XC2OmHFmQRAtjD2xWNhumdwqn70Y7RO4El6ugvOzGbAlx

Share:

Can Reverse Osmosis Make Volcanic‑Ash–Polluted Water Safe to Drink?

Special Treatments for Well Water Contaminated by Agricultural Fertilizers