As a smart hydration specialist and environmental scientist who has spent many hours under kitchen sinks and in utility rooms, I have seen the same reverse osmosis (RO) problems repeat in home after home. A system that once delivered crisp, low‑TDS drinking water suddenly slows to a trickle, starts leaking into the cabinet, or produces water that smells off. Homeowners often assume the unit is “worn out” or that RO itself is unreliable. In reality, most malfunctions trace back to a handful of predictable mechanical and water‑chemistry issues that are very fixable.

This article walks through why RO systems sometimes malfunction, how to recognize the root causes, and what you can realistically prevent or repair yourself. The explanations are grounded in manufacturer guidance from companies such as AXEON, Crystal Quest, and DuPont, engineering references from PuretecWater and J.Mark Systems, and field experience from working directly with families upgrading their home hydration.

What A Healthy RO System Is Designed To Do

Reverse osmosis is essentially controlled, high‑tech osmosis. In natural osmosis, water moves through a semi‑permeable membrane from a weaker solution toward a stronger one until concentrations balance. An RO system turns that natural flow around by using pressure to push water from the more concentrated side of a membrane to the purer side.

Engineering guides from PuretecWater describe RO as “hyperfiltration,” because the membrane separates at the molecular scale rather than just catching particles like a simple sediment filter. Modern drinking‑water membranes are usually thin‑film composite polyamide sheets, spiral‑wound into a compact cartridge. Under the right pressure and temperature conditions, they typically remove about 95 to 99 percent of dissolved salts and significantly lower many metals and other contaminants.

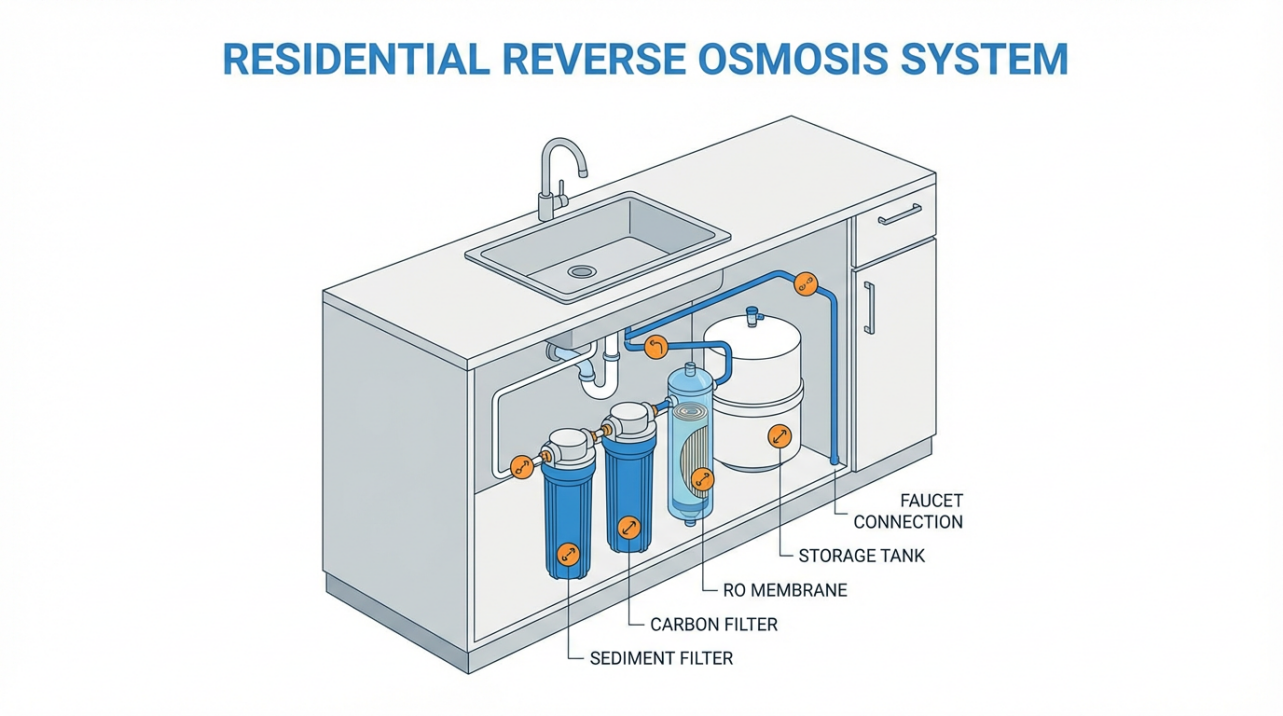

A complete residential RO system includes sediment and carbon pre‑filters, the RO membrane, a storage tank, a flow restrictor and automatic shutoff valve, and one or more polishing or remineralizing stages. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency describes this type of setup as a point‑of‑use system when it serves a single faucet, usually under the kitchen sink.

Two performance ideas are important for understanding malfunctions. Rejection rate is how much of a given contaminant the membrane removes. University extension materials summarized in the Viomiwater article show, for example, that a membrane rated for around 85 percent nitrate rejection can knock 40 milligrams per liter down to about 6 milligrams per liter, bringing it below the federal health standard, while 80 milligrams per liter of nitrate would still leave treated water above the limit. Recovery rate is the fraction of feed water that becomes treated water. Typical home systems are designed for roughly 20 to 30 percent recovery, meaning that if 100 gallons per day enter the unit, only about 20 to 30 gallons become drinking water and the rest goes to the drain as concentrate.

PuretecWater’s design examples for larger systems show how this concentrate stream works. At 80 percent recovery, 100 gallons per minute of feed water might give 80 gallons per minute of permeate and 20 gallons per minute of concentrate, and if the feed water had 500 milligrams per liter of dissolved salts, the concentrate would be roughly five times as salty, around 2,500 milligrams per liter. That concentration factor is why scaling and fouling can become serious problems if the system is pushed beyond its design limits.

Temperature and pressure also play a large role. The Viomiwater technical explainer notes that RO production typically drops about 1 to 2 percent for every degree Fahrenheit below about 77°F. When feed water is nearer 45°F, which is common for groundwater in cooler seasons, the same membrane may produce only about half as much water as it would with warmer feed water. Crystal Quest’s whole‑house RO guide and Rotec’s troubleshooting guidance both emphasize that most systems are designed around feed pressures in roughly the 40 to 60 psi range, with some whole‑house units using higher pump pressures.

When those basic design assumptions about pressure, temperature, and pretreatment are not met, malfunctions follow.

How RO Problems Usually Show Up At Home

Despite the intimidating hardware, RO systems tend to fail in familiar ways. AXEON’s troubleshooting guide, Moormechanic’s homeowner tips, and field experience all align on a core set of symptoms.

Low water production is often the first thing people notice. The dedicated RO faucet that used to fill a glass quickly might slow to a thin stream or take several minutes to fill a pitcher. Sometimes the system appears to shut down entirely, delivering little or no water.

Leaks are the next big concern. These may show up as a damp cabinet floor, water beading around filter housings, or a small but persistent puddle under the storage tank. Guides from AXEON, Nu Aqua, and Parker & Sons consistently point to fittings, housings, and tanks as the most common leak locations.

Changes in taste, smell, or clarity are another red flag. Cloudy or murky water, metallic or chemical tastes, and unusual odors signal water‑quality issues. AXEON and Moormechanic both note that visible particles, a sudden “flat” taste, or a return of the tap’s original odor all imply filters or the membrane are no longer doing their job.

Unusual noises also matter. Gurgling from the drain, buzzing around the pump or transformer, whistling at tees, or vibration against the cabinet are all described in AXEON’s and Rotec’s noise troubleshooting advice. While many RO systems make some sound during operation, changes in noise often track back to pressure, flow, or air‑gap problems.

The key is that these surface symptoms rarely point to a single cause. Instead, several recurring root causes tend to sit underneath them.

Root Cause 1: Filters And Membranes Are Overdue Or Fouled

In point‑of‑use systems, the most common reason an RO unit “fails” is simply that filters and membranes have been left in service too long. Every manufacturer guide in the research set, from Moormechanic to AffordableWater and Crystal Quest, emphasizes replacement intervals, because clogged filters and fouled membranes choke flow and allow breakthrough of contaminants.

Fouling is the accumulation of unwanted material on or in the membrane. Technical sources such as Chunkewatertreatment, Samco, and J.Mark Systems describe several fouling types. Particulate or colloidal fouling comes from fine solids like clays, iron oxides, and colloidal silica. These form a cake layer that physically blocks water flow. Organic fouling stems from natural organic matter, oils, and greases that coat the membrane surface. Biofouling occurs when bacteria and other microorganisms form biofilms. Scaling is different; it involves sparingly soluble salts, such as calcium carbonate or calcium sulfate, precipitating and hardening on the membrane as the concentrate becomes more saturated.

The consequences are similar in practice. Permeate flow drops, differential pressure across the membrane increases, and in more advanced systems energy use rises. J.Mark Systems notes that many operators treat a roughly 10 percent drop in normalized permeate flow or a 15 percent increase in pressure drop as a trigger for chemical cleaning. In homes, the signal is simpler: the faucet slows down or the storage tank never seems to fill.

A practical example helps. Consider a membrane initially producing 50 gallons per day with healthy pre‑filters and moderate feed water. If particulate and organic fouling reduce normalized flux by 20 percent, the same unit might now only produce about 40 gallons per day under identical conditions. If the homeowner has also added another user of that water, such as a refrigerator dispenser, the apparent shortage can feel much worse.

Filter neglect accelerates fouling. Sediment and carbon filters are there to capture suspended solids and chlorine before they reach the membrane. Crystal Quest’s whole‑house RO guide lists typical pre‑filter life in the range of about 12 to 24 months in those high‑capacity systems, while Moormechanic and AffordableWater suggest 6 to 12 months for smaller point‑of‑use units, depending on water quality and usage. When these cartridges are left in place beyond their intended life, they become restrictive, which lowers pressure at the membrane, and they allow more particulate and oxidants to hit the membrane itself.

Scaling is even more insidious. Chunkewatertreatment and J.Mark Systems both describe how high hardness and high system recovery push the concentrate above the solubility limits of salts such as calcium carbonate and calcium sulfate. That scale then builds up on the membrane surface, permanently reducing permeability if not cleaned in time. PuretecWater’s recovery and concentration factor example makes this clear at a system level: at 80 percent recovery with moderately mineralized water, the concentrate can carry several times the dissolved solids of the feed.

From a homeowner’s perspective, the fixes are straightforward but must be consistent. Replace pre‑filters and post‑filters on the manufacturer’s schedule, taking into account local water quality and usage, and plan on membrane replacement about every two to three years in most residential applications, as echoed by Moormechanic, Crystal Quest, and AffordableWater. In hard‑water areas or on whole‑house RO, pretreatment such as softening or antiscalant dosing—described in the Crystal Quest and Chunkewatertreatment guidance—is often needed to prevent repeat scaling problems.

Chemical cleaning is more common in industrial and large commercial systems than in under‑sink units, but the principles are similar. The detailed review of RO fouling and cleaning techniques in ScienceDirect, along with J.Mark Systems’ maintenance guide, explains that acidic cleaners target mineral scale and metal oxides, while alkaline and surfactant cleaners address organic deposits and biofilms. Enzymatic and oxidizing agents such as hydrogen peroxide or ozone can help with biological fouling but must be chosen carefully to avoid damaging the polyamide membrane. For a homeowner, that level of cleaning usually means bringing in a professional familiar with manufacturer limits.

Root Cause 2: Pressure, Temperature, And Flow Problems

An RO system lives and dies by pressure and temperature. The physics are simple: more pressure and moderate temperature mean more water pushed through the membrane. Too little pressure or very cold water starve the system.

Rotec’s troubleshooting guide and several residential sources point out that most RO systems are designed for feed pressures in roughly the 40 to 60 psi range. Crystal Quest’s whole‑house systems often run higher pump pressures at the membrane, but even there, feed pressure to the skid should remain stable. When incoming water pressure falls below the specified range, permeate flow drops dramatically. AXEON’s homeowner troubleshooting checklist explicitly includes checking that inlet pressure meets the minimum and suggests adding a booster pump if needed.

Temperature interacts with this pressure sensitivity. Viomiwater’s performance explainer cites engineering data showing RO production dropping roughly 1 to 2 percent for every degree Fahrenheit below approximately 77°F. That means water at 47°F could reduce output by on the order of 60 percent compared with warmer water, even if pressure and everything else stay the same. Many of the calls I get from homeowners about “sudden” RO slowdowns in late fall or winter turn out to be this cold‑water effect combined with filters that are already marginal.

The internal plumbing of the system can amplify or relieve these issues. The flow restrictor and automatic shutoff valve control how much concentrate leaves the membrane and when the system stops sending water to the tank. AXEON troubleshooting notes that a clogged or incorrectly sized flow restrictor can both reduce water production and waste more water than necessary. Rotec echoes that persistently high waste‑water flow or continuous drain flow when the tank is full often indicate a faulty shutoff valve.

The storage tank itself is another critical variable. Residential tanks use an internal bladder and air charge to deliver pressure to the faucet. AXEON and Moormechanic both describe low tank pressure or a failing bladder as common causes of poor flow: the membrane still produces water, but the tank never pressurizes correctly. The usual diagnostic step is to shut off the feed, drain the tank completely, then measure the air side pressure with an ordinary pressure gauge at the tank valve. If the bladder has failed, water may exit from the air side or the pressure will not hold, and the tank needs replacement.

Flow problems also arise when filters clog. AffordableWater and AXEON emphasize that clogged sediment and carbon filters restrict flow into the membrane housing, effectively lowering pressure at the membrane even if street pressure is fine. For homeowners, this is one more reason not to treat the six‑ or twelve‑month filter reminder as optional.

In practical terms, when I evaluate a sluggish RO system in a home, I almost always check four things in the same visit: incoming pressure at the system, feed water temperature, the age and condition of pre‑filters and the membrane, and the storage tank pressure. Addressing those together usually restores normal production without replacing the entire unit.

Root Cause 3: Leaks, Tanks, And Fittings

Leaks are both the most stressful symptom for homeowners and one of the most preventable. Detailed leak guides from Nu Aqua, AXEON, Parker & Sons, and AppliancePartsPros all converge on a few vulnerable points.

Filter housings are a classic culprit. Nu Aqua notes that loose housings, worn or mis‑seated O‑rings, or hairline cracks in the plastic can all create slow drips around the canister. Every time filters are changed, the O‑ring should be inspected, cleaned, lightly lubricated with a manufacturer‑approved lubricant if recommended, seated properly, and the housing tightened firmly but not over‑torqued. AXEON likewise warns that overtightening can deform O‑rings or crack housings.

Faucets and quick‑connect fittings are the next weak link. Over time, faucet gaskets and washers flatten or crack, especially if the faucet is bumped or used as a handle to pull oneself up from the sink area. Nu Aqua explains how leaks at the faucet base often show up as water pooling around the fixture or slow drips even when the system is not running. Quick‑connect or compression fittings on tubing can also loosen slightly, or tubing that was not cut squarely during installation can fail to seal perfectly. Most leak guides recommend re‑cutting the end square, pushing the tubing fully into the fitting, then gently pulling back to engage the internal seal.

The feed‑water adapter and drain connection can also leak if not installed correctly. Nu Aqua specifically calls out the importance of using thread seal tape on threaded adapters and ensuring that the leak stop valve, where present, is correctly assembled with its absorbent puck in place and tubing fully inserted. AppliancePartsPros and Rotec both point out that blocked or mis‑drilled drain saddles and air gaps not only cause noise but can also send water backing up into cabinets.

Storage tanks themselves can leak either at the threaded connection or due to corrosion or damage to the shell. Parker & Sons notes that tanks have a finite life, often around ten years in typical residential service, and recommends annual professional inspection in addition to homeowner checks, especially where RO is protecting high‑value flooring or cabinetry.

A useful way to think about leaks is to combine careful observation with simple testing. Turn off the feed and tank valves, dry everything thoroughly, then turn the feed back on while the tank is closed and watch for new moisture. If nothing appears, open the tank valve and observe again. This isolates whether the leak is on the high‑pressure feed side, the low‑pressure permeate side, or the storage tank path. Most homeowner‑level fixes involve tightening or replacing fittings, replacing O‑rings or housings, or swapping a tank; more complex issues, such as persistent leaks near pumps, transformers, or control panels on whole‑house or industrial units, are where professional help is justified.

Root Cause 4: Water Quality Changes That Look Like “System Failure”

Sometimes an RO system is working exactly as designed, yet the water still tastes or smells wrong. That feels like a malfunction from the kitchen sink, but in many cases it actually reflects the limits of what RO can and cannot remove.

RO membranes are excellent at rejecting dissolved ions and many larger organic molecules. PuretecWater’s technical guide notes that properly designed systems typically remove about 95 to 99 percent of dissolved salts. The Viomiwater article and university extension materials emphasize similar strengths for metals such as lead, arsenic, and chromium, and for inorganic contaminants like nitrate and fluoride. RO membranes also block many bacteria and protozoan cysts and, when combined with appropriate pre‑filtration and disinfection, contribute to robust microbiological protection.

However, several sources, including Viomiwater, university extension bulletins, and water‑treatment provider literature, underline that RO does not effectively remove certain dissolved gases. Hydrogen sulfide, which causes a rotten‑egg odor, is a prime example. Because hydrogen sulfide is a small, uncharged gas, it tends to pass through polyamide membranes. Homeowners install a point‑of‑use RO unit, see TDS drop dramatically, but notice that the sulfur smell persists in the glass. In those cases, the RO system did its job on dissolved solids; it was simply never designed to be a standalone hydrogen sulfide solution. Upstream oxidation and filtration or sulfur‑specific media, often combined with activated carbon, are usually required.

Carbon dioxide behaves differently but also undermines expectations. Engineering references summarized in the Viomiwater guide explain that RO membranes do not effectively remove dissolved carbon dioxide. When CO₂ passes into the permeate and reacts with water, it forms carbonic acid and gently lowers the pH. At the same time, RO removes many of the minerals that would otherwise buffer the water. Various health and water‑quality organizations, including the World Health Organization, have noted that RO water tends to be low in minerals and can end up mildly acidic, typically somewhere around pH 6 to 7.

In real homes, this can show up as slightly more corrosive behavior toward some metals over very long time frames or a “flat” taste that some people find less satisfying. Providers such as Crystal Quest address both concerns by using remineralizing post‑filters that add small amounts of calcium and magnesium back into the water, modestly raising pH and improving mouthfeel. It is also worth keeping perspective: those same public‑health sources emphasize that most essential minerals come from food, not from water, so drinking low‑mineral RO water is not a health risk for most people when diet is adequate.

Water quality changes can also trace back to simple filter neglect. AXEON, Rotec, Moormechanic, and AffordableWater all stress that expired carbon filters lose their ability to remove chlorine, chloramine, and many organic compounds. In systems using thin‑film composite membranes, losing carbon protection can also damage the membrane itself through oxidation, reducing both rejection and taste performance. Annual or semi‑annual sanitization, as recommended by Moormechanic, Nu Aqua, and AffordableWater, helps prevent bacterial growth in storage tanks and tubing that can otherwise cause earthy or musty tastes even when the membrane is fine.

A subtle but important example comes from nitrate treatment. The Viomiwater explainer describes how an RO membrane with about 85 percent nitrate rejection can reduce 40 milligrams per liter of nitrate to roughly 6 milligrams per liter, which meets the federal standard. If source water suddenly rises to 80 milligrams per liter due to agricultural changes, the same membrane, in the same system, would produce water that no longer meets the standard. From a homeowner’s perspective, nothing “broke” in the RO unit; the water simply changed enough that the original design is no longer sufficient, and additional or upgraded treatment is needed.

Root Cause 5: Maintenance And Design Gaps In Whole‑House And Industrial Systems

For families investing in whole‑house RO or businesses running industrial membranes, malfunctions often reflect system‑level design and maintenance gaps rather than a single bad filter or tank.

Crystal Quest’s whole‑house RO guide points out that these systems routinely handle 300 to more than 7,000 gallons per day, often at pump pressures between about 150 and 250 psi at the membrane. They also represent a significant capital investment, frequently in the range of a few thousand to many thousands of dollars. At that scale, skipped maintenance or poor pretreatment quickly becomes expensive.

Industrial‑focused sources from DuPont and J.Mark Systems detail how fouling and scaling impact large RO trains. DuPont notes that with proper pretreatment and maintenance, membranes can last on the order of six years, whereas inadequate cleaning or pretreatment can cut that life sharply. Both DuPont and J.Mark Systems emphasize the importance of monitoring normalized permeate flow, differential pressure, feed and concentrate conductivities, and other metrics. Many plants use thresholds such as a 10 to 15 percent decline in normalized flux or a similar increase in pressure drop as a trigger for clean‑in‑place events.

Cleaning itself is nontrivial. DuPont observes that mineral scaling can often be removed in a six‑ to eight‑hour cleaning on closed‑circuit RO systems, while organic fouling may require one to two days of carefully controlled chemical recirculation. The comprehensive fouling review on ScienceDirect catalogs conventional and advanced cleaning methods, from backwashing and forward flushing to specialized chemical or osmotic backwashing, ultrasonic fields, and electric fields, each with trade‑offs in effectiveness, membrane stress, and energy cost.

All of this underscores a crucial point for home‑owners considering whole‑house RO. These systems behave more like small industrial plants than oversized under‑sink filters. Crystal Quest recommends weekly quick checks of feed pressure, pump pressure, permeate pressure, flows, and leaks, along with monthly pre‑filter inspections and total dissolved solids testing, and annual professional inspection and sanitization. DuPont similarly highlights the value of remotely monitored systems and periodic expert visits for facilities new to RO.

In my experience, whole‑house RO makes sense when well water or small‑system municipal water has multiple serious issues, such as high TDS, multiple metals, and problem organics, and when the household is prepared for the added maintenance. For many homes on regulated city water that already meets safety standards, a more layered approach—simple point‑of‑entry filtration or softening where needed, combined with point‑of‑use RO at critical taps—is more practical and less prone to dramatic malfunctions. That is very much in line with the layered strategy recommended in the Viomiwater article and by several water‑treatment providers.

A Simple Symptom‑To‑Cause Cheat Sheet

While RO troubleshooting can get technical, it helps to summarize how common surface symptoms map to internal causes and practical actions.

Visible symptom |

Likely internal cause |

What usually helps in practice |

Slow or no flow at RO faucet |

Clogged pre‑filters or membrane, low feed pressure, cold feed water, failing tank |

Replace filters, check pressure and temperature, test and recharge or replace tank |

Cloudy water, odd taste, or odors |

Expired carbon filters, fouled membrane, bacterial growth, dissolved gases like H₂S |

Replace filters, sanitize system, test for sulfur or other issues and add pretreatment |

Continuous drain flow or high waste‑water volume |

Faulty flow restrictor or shutoff valve, incorrect recovery settings |

Inspect and replace restrictor or valve, adjust recovery to design range |

Leaks around housings, fittings, or tank |

Loose or cracked housings, worn O‑rings, mis‑cut or loose tubing, aging storage tank |

Reseat or replace O‑rings, re‑cut and reinsert tubing, replace damaged parts or tank |

New buzzing, whistling, or gurgling noises |

Air in system, clogged drain or air gap, unstable mounting, pump strain |

Bleed air, clear and re‑route drain, stabilize unit, evaluate pump condition |

Even without instruments, this kind of mapping helps homeowners think like a technician and describe issues more clearly when they do call a professional.

Thinking Like A Smart Hydration Specialist At Home

The most reliable RO setups I see in the field are not the most expensive; they are the ones whose owners treat them like a small appliance that deserves routine attention, not a black box that can be ignored for five years. The science‑backed guidance from AXEON, Rotec, Crystal Quest, J.Mark Systems, and others all point in the same direction.

Start by matching the system to your water. If you are on well water with hydrogen sulfide, iron, or very hard water, address those issues with pretreatment such as softening, sulfur media, or iron filtration before the RO. If you are on municipal water with already decent quality but want extra protection from specific contaminants like lead or nitrate, a point‑of‑use RO unit with solid carbon pre‑filtration may be enough. In either case, a basic water test and a quick read of local consumer confidence reports go a long way.

Once a system is installed, adopt a simple maintenance rhythm. Change sediment and carbon filters on schedule, not when taste finally turns. Use a TDS meter occasionally to track how permeate quality compares with feed water; rising TDS over time on the RO faucet, with stable feed TDS, is a strong clue that the membrane is nearing the end of its life. Sanitize the tank and lines annually or as your manufacturer recommends. Glance at pressures and listen for new noises when you are under the sink for any reason.

Pay attention to seasons. If your water source cools significantly in winter, expect flow to decrease and plan accordingly, perhaps by drawing water earlier for holiday cooking or considering a larger tank if your usage spikes. If your source is more turbid or high‑TDS in wet seasons, recognize that membranes and filters will work harder and may need replacement sooner, a pattern echoed in variable‑TDS research from lagoon and wastewater studies.

Finally, know when to call in a professional. Persistent leaks you cannot trace, repeated membrane failures despite good pretreatment, unexplained electrical or pump behavior, or whole‑house or industrial systems that drop performance are all better handled by technicians who work with these systems daily. As DuPont and J.Mark Systems stress, the cost of preventive maintenance is almost always lower than the cost of unplanned downtime and premature membrane replacement.

FAQ

How often should I replace filters and membranes to avoid malfunctions?

Most residential guides in the research set, including Moormechanic, AffordableWater, and Crystal Quest, converge on replacing sediment and carbon filters about every 6 to 12 months in point‑of‑use systems, and roughly every 12 to 24 months in many whole‑house setups, depending on water quality and usage. RO membranes typically last around 2 to 3 years in home systems with good pretreatment, while DuPont notes that industrial membranes can run on the order of six years under carefully controlled conditions. If you notice slow flow, rising TDS, or recurring taste and odor issues earlier than that, treat those as performance flags and not just as nuisances.

Is RO water “too pure” or unhealthy to drink?

It is true that RO removes minerals along with unwanted contaminants, and public‑health organizations such as the World Health Organization have pointed out that RO water is low in minerals and can be slightly acidic. However, those same sources emphasize that most essential minerals come from food rather than water for people on normal diets. In practice, RO water from a properly maintained system is safe to drink for most individuals. If you dislike the taste of very low‑mineral water or want to fine‑tune pH, remineralizing post‑filters, like those described by Crystal Quest, can add a small amount of calcium and magnesium back for better flavor and a bit more buffering.

When should I call a professional instead of fixing an RO problem myself?

Replacing filters, checking tank pressure, re‑seating tubing in quick‑connect fittings, and sanitizing an under‑sink system are within reach for many homeowners who are comfortable following manufacturer manuals step by step. If you encounter persistent leaks after several attempts, see unexplained drops in performance on a whole‑house or high‑pressure system, or need membrane cleaning with specialized chemicals, the balance shifts strongly in favor of professional help. Industrial guidance from DuPont and J.Mark Systems and whole‑house recommendations from Crystal Quest all highlight that trained technicians are best placed to handle complex clean‑in‑place procedures, electrical diagnostics, and system redesigns when source water or building needs change.

A well‑designed and well‑maintained RO system should be a quiet, almost invisible partner in your home hydration strategy. When you understand how it works, what it is good at, and where its weak spots are, you are far better equipped to keep it running smoothly and to choose the right mix of filters, pretreatment, and professional support for your family’s long‑term water wellness.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/44355425/Trouble_Shooting_in_Water_Treatment_Process_for_Variable_TDS

- https://ephidsweb.web.illinois.edu/files/pwc/OWTS_Final_Septic_System_Users_Guide2.pdf

- http://ccc.chem.pitt.edu/wipf/Web/LCMS%20trouble%20shooting.pdf

- https://www.owp.csus.edu/operator-training/courses/preview/tmw.pdf

- https://reclaim.cdh.ucla.edu/filedownload.ashx/form-library/ThYB9n/ChemicalPretreatmentForRoAndNfHydranautics.pdf

- https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/233fa6c3-18c8-47e6-9d94-6bb65abaf81a/content

- https://do-server1.sfs.uwm.edu/visit/N59418026T/pub/N86896T/reverse-osmosis__manual__operation.pdf

- https://mooremech.net/reverse-osmosis-system-maintenance-tips/

- https://www.affordablewaterinc.com/reverse-osmosis-maintenance-tips-for-first-time-owners

- https://chunkewatertreatment.com/fouling-and-scaling-on-membrane-filtration/

Share:

Understanding Valve Failure Indicators in Smart Home Water Systems

Three Early Signs of Wastewater Pipe Blockage to Watch For