As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time under sinks, inside equipment rooms, and next to humming RO skids in food plants. When a reverse osmosis system is producing great-tasting water day after day, nobody thinks about the tiny check valve hidden in the tubing. When that little part fails, though, tanks stop filling, membranes get stressed, and sometimes water purity quietly drifts in the wrong direction. The goal of this article is to make sure that never happens to you.

In what follows, I will walk through what RO actually does, what a check valve is, where it sits in your system, and why both household and industrial RO absolutely depend on it. I will also share practical, science-backed guidance drawn from organizations such as the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension, Puretec, Aquatech Trade, DFT Inc., and several valve manufacturers that specialize in water and wastewater systems.

How Reverse Osmosis Really Works in Your System

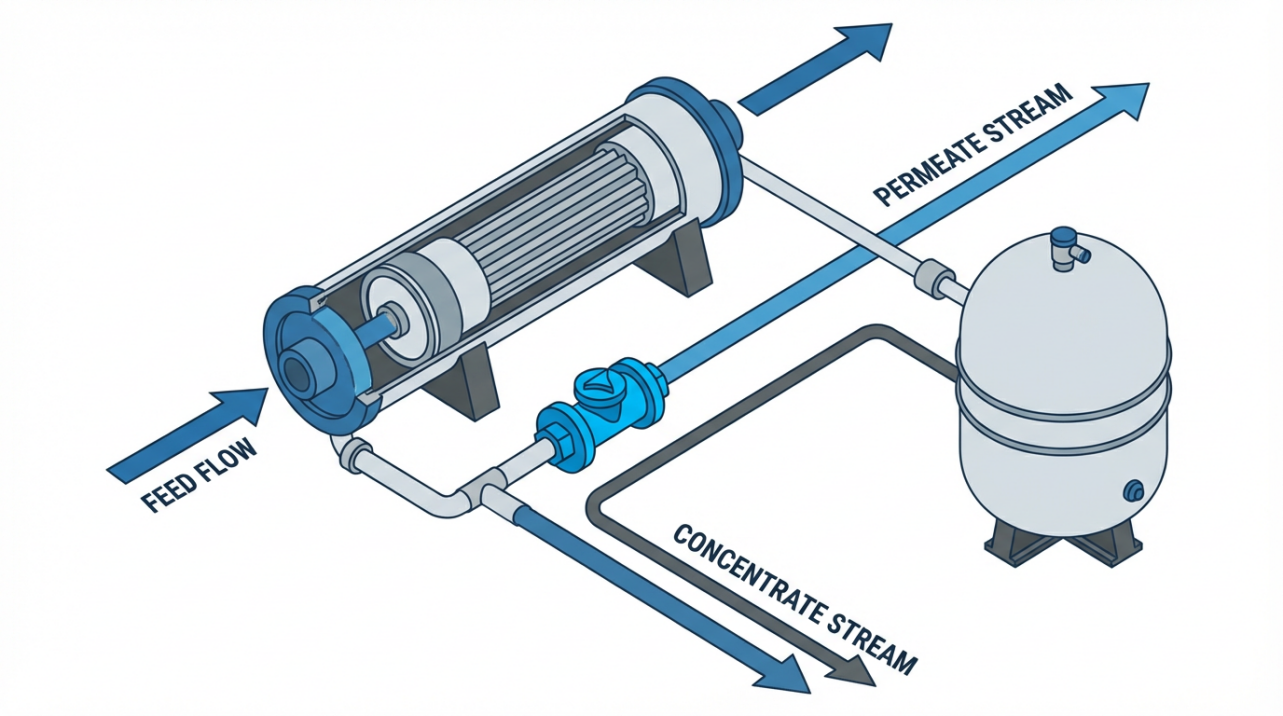

Reverse osmosis is more than “a fancy filter.” As the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension and Puretec explain, RO is a pressure-driven membrane process. Water is pushed against a semi-permeable membrane so that relatively clean water squeezes through, leaving many dissolved contaminants behind.

Inside any RO unit, whether under a kitchen sink or on an industrial skid, the incoming water stream is split into three conceptual streams. Feed water is what enters the RO membrane housing. Permeate or product water is the purified water that has passed through the membrane and goes to the faucet, process line, or storage tank. Concentrate or brine is the reject stream that washes away the salts and other contaminants that did not pass through the membrane.

Household membranes usually make roughly 10 to 35 gallons of treated water per day, according to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension. Only a fraction of the feed becomes permeate; many point-of-use RO units are designed around about 20 to 30 percent recovery. That means for 100 gallons per day entering the system, you might get 20 gallons per day of drinking-quality water and about 80 gallons per day of wastewater carried away as concentrate.

Performance depends strongly on pressure and flow control. Higher feed pressure generally improves both contaminant rejection and water production, while water temperature and pH also matter. Cold well water, for example, can sharply cut production; the University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension notes that water around 45°F may yield roughly half the output of the same system at about 77°F. To manage all of this, complete RO systems include prefilters, the membrane, a flow regulator on the brine line, a storage tank, a postfilter, and a small set of valves.

Among those valves, the check valve is one of the smallest but most critical.

What Is a Check Valve, Really?

In simple terms, a check valve is a one-way gate for water. Valve specialists such as Valveman, Hawle, and other industrial references define a check valve (also called a non-return or one-way valve) as a self-acting device that allows flow in only one direction and automatically blocks reverse flow without any handle, motor, or controller.

Internally, a check valve has an inlet, an outlet, and a closing element that moves in response to pressure. In its resting state, it is closed. When the pressure at the inlet side rises high enough, the closing element lifts or swings away from its seat and allows water to pass forward. If inlet pressure falls or outlet pressure tries to push back, the closing element snaps shut and blocks reverse flow.

A key concept from check-valve manufacturers such as Hawle and FSWelsford is cracking pressure. This is the minimum upstream pressure at which the valve just begins to open and allow detectable forward flow. If the cracking pressure is set too low for a given system, the valve may as well be open all the time. If it is too high, the valve may rarely open fully, adding unwanted resistance and causing unstable behavior at low flows.

Unlike ball valves or butterfly valves, check valves do not need any external control. They sense the pressure differential between inlet and outlet, react automatically, and then sit quietly in the line until needed again. In drinking-water and process systems, check valves are widely used to prevent backflow that could contaminate clean water lines or damage pumps and membranes upstream.

Where Check Valves Sit in an RO System

In a typical undersink drinking-water RO unit with a pressurized storage tank, the check valve lives on the purified water line between the membrane housing and the tank. Natrade, a supplier specializing in RO components, describes this device very succinctly as a one-way valve that allows water to flow toward the storage tank but prevents it from flowing backward into the RO membrane.

Systems that include an automatic shut-off valve and a pressurized tank depend on this arrangement. As DFT Inc., a check-valve manufacturer with decades of experience in RO applications, points out, a full tank creates backpressure. If there were no check valve on the permeate line, that pressure could drive water backwards through the membrane and into the feed side.

In larger industrial and desalination plants, the layout is more complex but the principle is the same. Spring-assisted check valves appear on pump discharges, on product-water lines leaving membrane trains, and on concentrate lines where operators are concerned about water hammer and reverse flow. DFT Inc. recommends spring-assisted, non-slam nozzle-style check valves for brine and brackish water services in desalination facilities, specifically because they close quickly and cleanly as flow slows, reducing hydraulic shock and protecting membranes and pumps.

In public water systems and industrial plants, FSWelsford notes that multiple check valves are often installed in series at different points in the process to ensure that contaminated fluids can never find their way back into clean supply lines, even if one protective barrier fails.

Why RO Systems Need Check Valves

Protecting Membranes from Reverse Pressure

The RO membrane is the heart of your purification system and is designed for pressure on one side only. DFT Inc. explains that in RO setups with automatic shut-off valves and pressurized tanks, a full tank can generate enough backpressure to overwhelm the feed side if the permeate line is not protected by a check valve. Spring-assisted check valves on that line shut when tank backpressure exceeds the feed-side pressure, blocking reverse flow. When the tank pressure drops below the feed pressure again, those valves reopen automatically.

Without this protection, running an RO system is not recommended.

Natrade explicitly warns that operating an RO system without a check valve, or with a failed one, is risky because reverse flow can damage components and contaminate stored water. In practice, that means a failed check valve can quietly undo the work your membrane is doing, pushing treated water backward through a membrane that was never designed to be a two-way door.

Maintaining Water Purity and Preventing Cross-Contamination

One of the main jobs of a check valve in any water-treatment system is to stop contaminated water from traveling back into cleaner parts of the system. Aquatech Trade emphasizes that check valves perform an essential function in preventing reverse flow where potentially polluted water could re-enter clean water resources.

In an RO drinking-water system, there are several purity interfaces to protect. You want to keep concentrate and feed water from migrating toward the permeate side, and you want to keep stored water in the tank from migrating back into the membrane housing and prefilters. The University of Nebraska–Lincoln Extension reminds us that RO systems are not designed to be the primary barrier against microorganisms and that only microbiologically safe water should enter the system. If backflow were allowed, bacteria sitting in the tank or downstream piping could move into the membrane housing, where they are much harder to flush out and could slowly colonize internal surfaces.

By forcing purified water to move in only one direction toward the faucet and never back toward the membrane, a correctly sized and oriented check valve helps preserve the integrity of the “clean side” of the system.

Reducing Water Hammer and Mechanical Shock

Aquatech Trade describes water hammer as the phenomenon that occurs when moving water is suddenly forced to stop. If flow reverses before a valve is fully closed and then slams shut, the kinetic energy of the moving water converts into a high-pressure surge that travels through the pipeline almost at the speed of sound. Repeated extreme pressure spikes like this can fatigue or rupture piping, valves, and pump components; Aquatech notes that severe events can destroy a system and lead to repairs costing tens of thousands of dollars.

In RO systems, this risk appears wherever flow and pressure change quickly, such as when high-pressure pumps stop or when control valves close. Check valves specifically designed for non-slam operation, such as the spring-assisted nozzle-style designs promoted by DFT Inc., close rapidly and smoothly as flow decelerates, minimizing reverse flow distance and thus mitigating water hammer. Proco Products, which focuses on elastomeric check valves for water and wastewater, shows another approach. Their rubber duckbill check valves use a flexible elastomer body that flexes instead of slamming, dissipating surge energy and further limiting the risk of hydraulic shock.

Although the energy levels in a small household unit are far below those in a large desalination plant, the same principle applies. A check valve that closes decisively as flow stops helps protect upstream fittings and components from repetitive reverse surges whenever a pump or automatic shut-off valve cycles.

Supporting Stable Performance and Recovery

Because RO performance depends on pressure and flow balance, uncontrolled backflow is more than a mechanical hazard; it is a process-control problem. Durpro, which specializes in industrial RO optimization, highlights how crucial precision valve management is for consistent permeate quality and stable recovery. They describe how the concentrate (drain) valve and recycle valve are adjusted to set the ratio between concentrate and permeate, typically targeting about a three-to-one concentrate-to-permeate ratio in many applications.

Check valves are not tuning devices, but they enforce directionality so that all of the careful adjustment performed by flow restrictors, metering control valves, and recycle valves is not undone by water creeping backward through a line whenever pressures change. In this sense, a check valve is like the one-way door at the end of a carefully controlled corridor; it ensures that the carefully managed pressure and flow you create always move the process in the intended direction.

Check Valves versus Other RO Components

Because RO systems use several different small components that all influence pressure and flow, it is helpful to distinguish clearly between them. The following table summarizes roles for some of the key parts discussed in the technical references from Osmotics, Fresh Water Systems, Theroworld, Thinktank, Durpro, and Steelstrong.

Component |

What it does in an RO system |

Key risk if missing or mis-sized |

Check valve |

One-way valve that lets purified water move toward the tank or process line and blocks reverse flow; also used on pump discharge and concentrate lines in larger plants to prevent backflow and water hammer, as noted by DFT Inc. and FSWelsford. |

Reverse flow can damage membranes and pumps, recontaminate stored water, and contribute to water hammer events. |

Small device on the brine outlet that maintains the correct wastewater flow and backpressure across the membrane; Theroworld and Osmotics explain that this ensures the membrane sees enough pressure and that the purified-to-reject ratio stays near about one to three. |

If too open or missing, pressure drops, water quality worsens, and large volumes of water are wasted; if too restrictive, membrane stress and premature failure become more likely. |

|

Concentrate or recycle metering valves |

Adjustable control valves in industrial RO systems that Durpro and Thinktank describe; they fine-tune concentrate discharge and recycle flow to set the operating pressure, permeate rate, and recovery. |

Incorrect settings can improve short-term production but increase scaling, fouling, and membrane wear while degrading permeate quality. |

Gate or isolation valves |

On or off valves described by Steelstrong that allow sections of an RO system to be shut in for service or repairs and sometimes to roughly throttle flow between stages. |

Without proper isolation, safe maintenance is difficult and sections may need to be shut down unnecessarily. Throttling with the wrong valve can also create harmful pressure drops. |

A check valve’s job is purely directional control. Flow restrictors and metering valves are about how much water moves and at what pressure. All of them matter, but they solve different problems.

Types of Check Valves You Might Encounter around RO

Valve manufacturers such as Aquatech Trade, Valveman, Proco Products, DFT Inc., WSD, and Redhorse describe a wide catalog of check-valve designs. Not all of them appear in RO systems, but understanding the main characteristics helps you appreciate why a designer chooses one type over another.

Swing or flap check valves use a hinged disc that swings on a trunnion. Aquatech notes that this is the simplest and often lowest-cost design, widely used from homes to large industrial plants. When forward flow pushes the disc open, the passage area is large and the pressure drop is low. The swing motion tends to self-clean debris and there is minimal risk of clogging. However, swing checks are limited to horizontal or upward flows, are not ideal for pulsating flows, and can amplify water hammer because the disc has to travel a relatively long distance to close. The same source points out that steel swing checks can rust, stick, or jam with debris and typically last about five to seven years in demanding services such as sludges and slurries before needing replacement.

Ball and spring check valves, as described by Aquatech and Bestflow, rely on a ball or disc held against a seat, often with a spring. When inlet pressure exceeds the cracking pressure, the spring compresses and the ball lifts, allowing flow. When pressure drops or reverses, the spring pushes the ball back, closing the seat quickly. These designs are durable, compact, and effective at reducing water hammer. Their drawbacks include higher cost, lower flow capacity due to smaller passage areas, and the inconvenience that inspection often requires removing the valve from the line.

Duckbill elastomer check valves, brought into wide use in the 1980s according to Aquatech and Proco Products, take a different approach. A flexible rubber “bill” opens under positive internal pressure and collapses to seal under backpressure. These valves have no mechanical hinges or metal moving parts. Proco reports that rubber duckbill valves can last roughly 35 to 50 years in suitable services, resist rust and marine growth such as barnacles and algae, and naturally absorb surge energy rather than slamming, which makes them attractive for submerged outfalls and other harsh water and wastewater applications. Their limitations include sensitivity to very high temperatures and highly abrasive fluids, and the need to match the elastomer formulation carefully to the chemicals present in the water.

Silent or non-slam nozzle check valves, recommended by DFT Inc. for RO and desalination plants, are a specialized spring-based design in which a short-stroke disc or plug moves axially inside a streamlined body. Because the travel distance is short and the spring assists closure, these valves can shut very rapidly as flow decays, sharply reducing the amount of reverse flow and associated water hammer. DFT highlights that using materials such as nickel–aluminum bronze or duplex stainless steel for the body and internals helps these valves withstand continuous exposure to seawater and chlorides while resisting marine growth and corrosion.

Many other designs exist, including dual-plate wafer valves, piston check valves, and foot valves for pump suction lines, as detailed by Valveman, WSD, and Redhorse.

In RO-focused applications, however, the most common choices are compact spring-assisted inline valves for permeate lines, robust nozzle-type valves for high-pressure brine and product lines, and elastomeric duckbill valves for wastewater and marine outfalls.

Materials Matter: Matching Check Valves to RO Water

Selecting the right check valve for an RO system is not only about the internal mechanism; it is also about the materials that will touch the water. DFT Inc. stresses that RO check valves often face harsh conditions such as seawater, dissolved salts, chlorides, and treatment chemicals. Over time, these can degrade seals and housings and eventually contaminate processed water if the material choice is poor.

For seawater desalination and other high-chloride services, DFT notes that nickel–aluminum bronze and duplex stainless steels are widely used for valve bodies and internals because they offer superior resistance to corrosion and marine growth. Proco emphasizes the importance of elastomer formulation in duckbill valves; the exact rubber recipe makes the difference between a check valve that is deformed by sunlight or chemical attack and one that lasts decades in underwater service.

FSWelsford and WSD highlight that designers must consider fluid properties such as chemical reactivity, treatment chemicals, temperature, viscosity, and the required pressure range. In public water systems, check valves also appear at consumer premises and sanitary taps, so materials must be compatible with drinking-water regulations.

In point-of-use RO for kitchens or office break rooms, check valves are often compact plastic components with metal springs and internal seals chosen to handle modest pressures and typical tap-water chemistry.

In industrial RO, material and design choices are tailored much more aggressively to the specific feedwater, whether that is brackish groundwater, seawater, or complex industrial wastewater.

Symptoms of a Failing RO Check Valve

Because check valves are hidden inside housings or fittings, you usually notice their problems indirectly. Natrade, which focuses on RO components, points out several practical symptoms. One common sign is that the RO storage tank does not fill properly. When a check valve sticks open or fails, system pressure cannot build as designed. As a result, the automatic shut-off valve may not engage correctly, and the tank may remain low on water even though the feed is available.

Another symptom is that the tank fails to hold water. If purified water drains back through a faulty check valve toward the membrane and feed side whenever you stop using the faucet, the stored volume in the tank will drop between uses. Natrade recommends inspecting the check valve if the tank will not fill or hold water and checking whether the valve is stuck, cracked, or installed in the wrong direction.

They also caution that running without a check valve, or with one that has clearly failed, is not recommended. Beyond poor performance, there is a real risk that backflow can damage components and recontaminate stored water, undoing the benefit of having an RO system in the first place.

In normal use, Natrade notes that the lifespan of an RO check valve is roughly two to five years, depending primarily on feedwater quality and how frequently the system is used. Routine inspection and timely replacement help avoid sudden failures.

How Check Valves Fit into the Bigger Valve Picture in RO

Check valves never work alone. In RO systems, they operate in concert with flow restrictors, metering valves, and isolation valves to create the right hydraulic environment for the membrane.

Flow restrictors on the concentrate line, described by Theroworld, Osmotics, and Fresh Water Systems, are small devices that create the necessary backpressure inside the membrane housing. By regulating wastewater flow, they help maintain a typical purified-to-rejected water ratio near about one to three. If pressure inside the membrane is too low because of a missing or faulty restrictor, filtration efficiency drops and the total dissolved solids in your drinking water increase. Without any restrictor, water simply rushes to drain and very little water gets purified. If the restrictor is too tight, it can overpressurize and stress the membrane. Both Theroworld and Fresh Water Systems recommend treating “new membrane plus new flow restrictor” as a single maintenance step, because restrictors clog over time and must be properly sized to match the membrane’s production rate. For example, they note that a membrane rated around 75 gallons per day typically pairs with a restrictor rated near 450 to 500 milliliters per minute, which equates to roughly 170 to 190 gallons per day of restricted drain capacity.

In industrial RO, Durpro and Thinktank emphasize the role of metering control valves on concentrate and recycle lines. These valves are carefully adjusted, and often controlled by electric actuators, to set recovery and operating pressure. Durpro cautions that over-closing a concentrate valve may temporarily boost permeate output but will accelerate fouling, degrade permeate quality, and increase maintenance costs. Thinktank’s work on high-pressure metering control valves for challenging waters such as waste leachate and seawater shows just how much engineering goes into precise pressure control for RO.

Gate valves and other isolation valves, discussed by Steelstrong, are the “on–off switches” that allow technicians to take parts of an RO plant offline for maintenance or reconfiguration. By throttling or isolating sections, they protect membranes and other components from excessive pressure and keep maintenance safe and efficient.

Check valves thread through this landscape by doing one simple but essential job: making sure that every other valve’s work is not undone by water taking the easy route backward whenever pressures change.

Practical Guidance for Homeowners and Facility Managers

From a practical standpoint, the greatest value in understanding check valves is knowing when and how to pay attention to them.

At the household level, Natrade notes that many homeowners can install or replace an RO check valve themselves, as long as they follow basic installation steps and confirm the correct flow direction indicated on the valve body. If there is any uncertainty about orientation or compatibility, they recommend seeking professional guidance or using supplier resources. Because the typical lifespan is about two to five years, it is reasonable to align check-valve replacement with membrane changes or every second filter change, depending on how heavily the system is used.

From a system-design and facility-management perspective, insights from DFT Inc., Aquatech Trade, Proco Products, FSWelsford, and Durpro converge on a few key themes. First, never treat check valves as an afterthought, especially on high-pressure RO lines. They are critical to managing water hammer, protecting pumps, and preventing contamination. Second, match the valve type and material to the service. That includes resisting corrosion in saline or chemically treated waters, handling the right flow range and pressure, and respecting orientation requirements for specific designs. Third, integrate check valves into your monitoring routine. New noise, sudden changes in pressure behavior, tanks that no longer fill as expected, or signs of reverse flow are all reasons to inspect and, if necessary, replace the check valve before more serious damage occurs.

In specialized applications such as maple syrup concentration and certain industrial clean-in-place sequences, operators sometimes intentionally reverse flow through membranes to clean them. As one practitioner in a technical discussion observed, doing so in a system that also contains check valves raises questions about how the plumbing is arranged. In those cases, engineers design bypasses or alternative flow paths to route cleaning flows around or through specific valves in controlled ways. For standard drinking-water RO, however, there is no reason for water to reverse direction across the membrane, and check valves are installed specifically to prevent it.

FAQ about Check Valves in RO Systems

Can I run my RO system without a check valve?

You should not. Natrade explicitly advises that operating an RO system without a check valve, or with one that has failed, is not recommended. Without a functioning check valve, backpressure from a full storage tank or from downstream plumbing can push purified water backward through the membrane, stressing the membrane and risking contamination of the stored water.

How often should I replace the RO check valve?

There is no single calendar rule, but Natrade reports a typical lifespan of about two to five years, depending on feedwater quality and how often the system runs. If your tank is not filling or holding water properly, or if a professional service visit finds signs of reverse flow, it is wise to replace the check valve sooner. Many homeowners and technicians treat check-valve replacement as part of periodic membrane or major filter maintenance so that the valve is renewed before it fails.

Is water hammer really a concern in RO systems?

In large RO plants with high-pressure pumps and long pipelines, absolutely. Aquatech Trade and Proco Products describe how water hammer can create high-pressure shock waves that damage piping and valves and even destroy systems. That is why DFT Inc. promotes spring-assisted, non-slam check valves for RO and desalination plants, and why rubber duckbill check valves are popular in wastewater outfalls. At the household level, the forces are smaller, but the same physics applies. A properly selected, fast-closing check valve reduces the chances of pressure spikes and contributes to quiet, stable operation.

How is a check valve different from a flow restrictor in an RO unit?

A check valve is all about direction; it allows forward flow and blocks backflow. A flow restrictor is about rate and pressure; it limits brine flow to create the right backpressure on the membrane and maintain the intended permeate-to-concentrate ratio. As Theroworld, Osmotics, and Fresh Water Systems explain, you need both working together. The flow restrictor sets the membrane’s operating conditions, and the check valve ensures that purified water only moves toward your storage tank or faucet, never backwards into the membrane.

A well-designed RO system is a team effort between membranes, pumps, filters, and a surprisingly small number of strategically placed valves. Among those, the humble check valve plays an outsized role in protecting your water quality and your equipment. When you pair sound membrane and flow design with correctly chosen, well-maintained check valves, you are not just filtering water; you are building a reliable, long-term hydration system that keeps your household or facility supplied with clean, consistent water every day.

References

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/articles/reverse-osmosis-optimization

- https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/html/g1490/build/g1490.htm

- https://www.bestflowvalve.com/what-is-a-check-valve-how-does-check-valves-work.html

- https://cncontrolvalve.com/metering-control-valves-in-ro-systems/

- https://empoweringpumps.com/dft-why-check-valves-for-the-reverse-osmosis-industry/

- https://www.fswelsford.com/blog-and-articles/crucial-role-of-check-valves-in-piping-systems

- https://kanzotech.com/exploring-the-benefits-and-applications-of-check-valves-understanding-non-return-valves-in-modern-plumbing-systems/

- https://natradesource.com/check-valve-for-reverse-osmosis-systems/

- https://www.procoproducts.com/advantages-of-check-valves-in-water-wastewater-systems/

- https://www.redhorseperformance.com/blog/what-does-a-check-valve-do-everything-you-need-to-know?srsltid=AfmBOoq1a7G1ydFoEpwlke7X-1whHzDb_8Ah1maB2rjDnxyMm_ZnNDLq

Share:

How Capacitive Touch Control in Smart Faucets Achieves Water Resistance

Understanding the Effectiveness of 253.7 nm Wavelength UV Lamps