As a Smart Hydration Specialist and Water Wellness Advocate, I spend a lot of time looking inside the devices that stand between your tap and your glass. Again and again, one technology shows up in serious drinking water, air, and surface disinfection systems: ultraviolet-C light at about 253.7 nanometers.

You may see this marketed as “254 nm UVC,” “germicidal UV,” or simply a “UV sterilizer.” Behind the marketing, there is a very specific scientific reason this wavelength dominates high‑end water purification systems, hospital equipment, aircraft disinfection carts, and advanced food and beverage processes. In this article, we will unpack what 253.7 nm lamps actually do, how effective they really are, and how to use them wisely in home hydration systems.

I will stay close to published data from organizations such as Honeywell, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Environmental Protection Agency, ELGA LabWater, and peer‑reviewed food science research, while translating that evidence into practical guidance for real homes.

UV Light 101: Where 253.7 nm Fits

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is electromagnetic energy with wavelengths shorter than visible light and longer than X‑rays. Standard references divide it into three main bands. UVA covers roughly 315–400 nanometers and is the long‑wave UV that mostly reaches the ground, driving tanning and skin aging. UVB runs from about 280–315 nanometers, is largely filtered by the ozone layer, and is responsible for sunburn as well as vitamin D synthesis. UVC spans about 100–280 nanometers and is the shortest, most energetic band.

According to atmospheric measurements summarized by major scientific sources, essentially all natural UVC from the sun is absorbed by oxygen and ozone high in the atmosphere, so almost no UVC reaches Earth’s surface. That is why our everyday UV exposure is mostly UVA with a smaller UVB component, and why artificial UVC needs to be handled with care: our skin and eyes did not evolve under it.

For disinfection, the UVC band is the star. Both the CDC and UV germicidal irradiation literature describe the strongest germicidal action in the range from roughly 240–280 nanometers. Low‑pressure mercury vapor lamps, the workhorse of germicidal UV systems, emit most of their energy at 253.7 nanometers, which sits right inside this “most germicidal” window.

Why 253.7 nm Became the Workhorse Wavelength

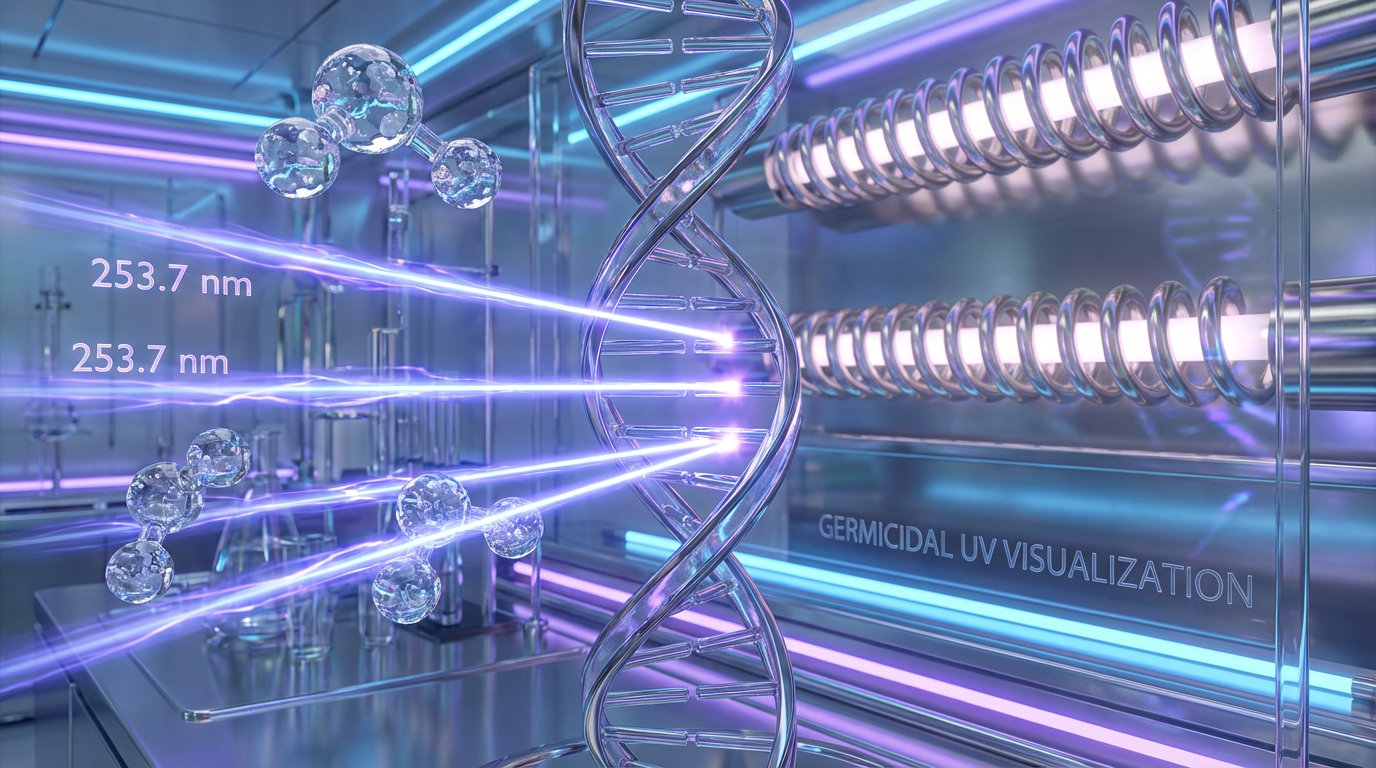

Microbiologists have known for decades that DNA and RNA absorb UV light most strongly around about 260–265 nanometers. When these nucleic acids absorb UVC photons, they undergo photochemical changes, especially the formation of pyrimidine dimers, that block replication and repair. In other words, if you hit microbes with UV near this absorption peak, you get very efficient inactivation.

Several lines of research converge on 253.7 nanometers as an almost ideal practical wavelength.

Scientific reviews cited by News‑Medical describe comparative experiments in which 253.7 nanometers emerged as the most effective germicidal wavelength among tested sources. The CDC notes that low‑pressure mercury lamps emit over 90 percent of their energy at 253.7 nanometers and that the maximal bactericidal effectiveness of UV lies between about 240 and 280 nanometers. Food preservation research on UV‑treated juices and purees identifies roughly 253.7 nanometers as a preferred processing wavelength in practice.

Commercial and engineering sources reach similar conclusions. LivingStarPlus, drawing on lamp performance data, points out that germicidal lamp output and effectiveness peak around 253–253.7 nanometers within the UVC band, and that this has become the standard design point for UVGI (ultraviolet germicidal irradiation) systems. HVAC and indoor air quality resources likewise describe about 253.7 nanometers as the optimal range for DNA absorption in microbes.

The final piece is technology. Low‑pressure mercury vapor lamps naturally emit a very strong, sharp spectral line at 253.7 nanometers. That means manufacturers can build lamps that are inexpensive, stable, and energy efficient while landing right next to the biological absorption peak. This combination of physics and biology is why 253.7 nanometer lamps power so many disinfection systems in hospitals, aircraft, water plants, laboratories, and serious home water purification setups.

How 253.7 nm UV Lamps Actually Inactivate Microorganisms

At the microscopic level, 253.7 nm lamps do not “burn” organisms in the way people often imagine. Instead, they drive very specific photochemical damage.

When bacteria, viruses, and other microbes are exposed to UVC, their DNA or RNA absorbs the light. Food science research on UV‑treated beverages describes this as photodimerization, where adjacent nucleotide bases form abnormal bonds (for example, pyrimidine dimers). Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation literature explains that these lesions block replication and interfere with vital cellular functions.

The result is that microorganisms become non‑infectious. They may not disintegrate immediately, but they lose the ability to multiply and cause disease. That is why many technical documents talk about “inactivation” rather than outright destruction.

One important nuance, highlighted in both UVGI and CDC guidance, is that some organisms can repair a portion of this damage through photoreactivation or dark repair. Because of that, UV systems usually target specific “log reductions” (for example, 99.9 percent inactivation) instead of claiming absolute sterilization. For many bacteria and viruses, a 90 percent reduction (one‑log) occurs at UV doses on the order of a few thousand microjoules per square centimeter, which corresponds to a few millijoules per square centimeter. More resistant spores and shielded organisms can require higher doses.

Dose is the key word. Technically called fluence, dose is the product of irradiance (how intense the UV field is at a given point) and exposure time. UVGI and EPA drinking water guidance both stress that dose depends on several real‑world factors:

Factor |

Why it matters for 253.7 nm effectiveness |

Lamp output and aging |

UV intensity drops as lamps age, even though they still appear to glow, so delivered dose falls unless lamps are replaced on schedule. |

Distance and geometry |

UV intensity decreases with distance and can be blocked by shadows; systems must account for the furthest and least‑exposed points in a reactor or room. |

Water clarity and UV transmittance |

Turbidity, dissolved organic compounds, and color absorb or scatter UVC, reducing how much light actually reaches microbes in water. |

Surface roughness and fouling |

Rough, porous, or dirty surfaces and biofilms can physically shield microbes, often requiring much higher doses for the same inactivation level. |

Exposure time and flow pattern |

Faster flow or poor mixing can reduce the time each microorganism spends in the high‑intensity zone, lowering effective dose. |

When I evaluate UV systems for home hydration, I treat the lamp’s wavelength as a given and spend more time looking at how the system manages these dose‑defining factors: pretreatment to improve water clarity, hydraulic design, and realistic lamp life.

What the Research Says About 253.7 nm Performance

Viruses, Including SARS‑CoV‑2

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation research shows that UVC inactivates a wide range of viruses, including both DNA and RNA viruses. The UVGI literature notes that RNA viruses tend to be especially sensitive to UVC compared with many DNA viruses.

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, multiple laboratories directly tested 253.7 nanometer lamps against SARS‑CoV‑2. Honeywell reports that several studies using its 253.7 nanometer UV systems demonstrated strong efficacy against the virus. A widely cited experiment by a team at Boston University achieved about a 99 percent reduction in SARS‑CoV‑2 on surfaces at a dose of five millijoules per square centimeter delivered by a 253.7 nanometer low‑pressure mercury lamp.

Researchers and manufacturers are careful to note that translating lab conditions to everyday environments is not straightforward. Real‑world effectiveness against COVID‑19, particularly for air disinfection in occupied spaces, depends on factors such as airflow, room geometry, and human behavior. Still, the underlying virology is clear: at sufficient doses, 253.7 nanometer lamps can reliably inactivate coronaviruses, including SARS‑CoV‑2.

Bacteria, Protozoa, and Spores

The CDC and EPA both treat UVC as a proven method for inactivating diverse microorganisms in water, air, and on surfaces. CDC summaries describe UV in the 210–328 nanometer range, with a maximum bactericidal effect between about 240 and 280 nanometers, as capable of inactivating bacteria, viruses, and fungal organisms. They note that bacterial spores are generally more resistant than vegetative bacteria and viruses, which matches dose‑response data from UVGI studies.

EPA’s ultraviolet disinfection guidance for drinking water systems gives more quantitative context. For many bacteria and viruses, 90 percent inactivation generally falls in a range of about 2,000 to 8,000 microwatt‑seconds per square centimeter. Regulatory frameworks grant utilities specific “log inactivation credits” for Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and viruses when UV reactors are validated under realistic operating conditions.

Consumer‑oriented sources echo this broad spectrum of action. Coospider and PureWater‑focused materials describe 254–253.7 nanometer UV systems as particularly effective against E. coli, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium, organisms that are known to resist conventional chlorination. Peer‑reviewed food science research on UV‑treated vegetable‑based beverages concludes that 253.7 nanometer UV‑C can inactivate pathogens and spoilage organisms while preserving vitamins and sensory quality better than thermal pasteurization, as long as product properties and dose are carefully managed.

Real‑World System Data

It helps to see how 253.7 nanometer lamps behave in full‑scale systems, not just petri dishes.

Honeywell’s aircraft UV Treatment System is one of the better documented examples. The second‑generation cart uses fourteen low‑pressure mercury UVC lamps at 253.7 nanometers, with eight lamps rated at 95 watts and six at 35 watts. At an operating speed of ten rows of seats per minute in a narrow‑body aircraft, on‑board measurements show that the system delivers doses of roughly 9.6 to 39.0 millijoules per square centimeter on a variety of cabin surfaces. Laboratory testing and on‑aircraft trials reported greater than 99.9 percent reduction of tested pathogens on tray tables, armrests, lavatory seats, and other high‑touch surfaces.

In the water world, ELGA LabWater describes low‑pressure UV systems that place a 253.7 nanometer lamp inside a central quartz tube within a stainless‑steel chamber, with water flowing through the space around the lamp. At low doses, the 253.7 nanometer line inhibits microbial replication; at higher doses, it becomes biocidal. ELGA combines this UV treatment with reverse osmosis, ion exchange, and filtration in a recirculating loop to maintain ultra‑pure lab water with total organic carbon below about three parts per billion and bacterial counts below about 0.001 colony‑forming units per milliliter.

EPA surveys also show thousands of municipal UV installations worldwide, many using low‑pressure mercury lamps at about 253.7 nanometers, delivering validated multi‑log reductions of protozoa and viruses in surface water plants.

Home systems draw on the same physical principles, scaled and packaged for residential flow rates and budgets.

253.7 nm UV Lamps in Water Purification and Home Hydration

For drinking water, 253.7 nanometer UV lamps are rarely used on their own. Instead, they sit in a treatment train as a final “polishing” step.

PureWater‑focused guidance explains UV water sterilization as follows. A specialized UV lamp emitting around 253.7 nanometers is enclosed in a housing so that water flows in a thin layer around the lamp. As water passes the lamp, bacteria, viruses, algae, and molds are exposed to the intense germicidal field. Their DNA and RNA are damaged, preventing them from functioning or reproducing. Because UV inactivates rather than filters out particles, the process is typically installed after mechanical filtration or other cleaning steps.

EPA and UVGI documents reinforce this idea of UV as a disinfection barrier layered on top of filtration. For drinking water, utilities remove turbidity and most particles first, then apply UV for microbiological safety, and in many cases still add a low dose of chlorine or chloramine afterward to maintain a residual in the distribution system.

Lab and industrial water systems follow a similar pattern. ELGA removes UV‑absorbing species and most organics by reverse osmosis and ion exchange before UV treatment, so that the 253.7 nanometer energy is focused on trace contaminants and microbes instead of being wasted on bulk impurities.

In homes, the same logic applies. When I evaluate a smart hydration setup, I look for sediment and carbon filtration to take out dirt, rust, and organic color, possibly reverse osmosis for dissolved solids if needed, and then a UV stage at the point where water is about to reach your faucet, refrigerator dispenser, or dedicated hydration tap.

From a user’s point of view, the benefits described across sources are compelling. UV disinfection at 253.7 nanometers is chemical‑free, leaving no residues, taste, or odor. PureWater resources emphasize that UV treatment does not alter pH, taste, color, or smell, which is a big advantage if you are sensitive to chlorine. UV is effective against chlorine‑resistant pathogens such as Giardia and Cryptosporidium. Once installed, systems generally have low energy consumption and modest maintenance, especially compared with ongoing purchases of chemical disinfectants.

At the same time, several limitations are essential to understand.

UV disinfection does not remove particles or dirt. Coospider’s educational materials emphasize that UV inactivates microorganisms but does not physically remove them from water or surfaces. That is why filtration and cleaning remain necessary.

UV performance is highly dependent on water clarity and UV transmittance. The food science review on UV‑treated beverages highlights poor penetration depth in turbid or highly absorbing liquids, noting that viscosity, dissolved solids, and scattering can strongly limit effectiveness. Rough or opaque surfaces may require up to about two orders of magnitude higher doses for comparable inactivation. In practice, that means a home UV system is a good fit for relatively clear water that has already been filtered, not for muddy or heavily contaminated sources.

UV also does not provide a disinfectant residual in plumbing. EPA’s guidance points out that UV systems leave no ongoing biocidal effect once water has left the reactor. Any organisms introduced downstream, for example in storage tanks or faucet aerators, are not controlled by the UV dose upstream. In municipal systems, this is addressed by combining UV with a small chlorine residual. In homes, it translates into regular cleaning of tanks and fixtures, and an understanding that UV is protecting water at the point of treatment, not everywhere in the plumbing.

Finally, UV does not remove chemical contaminants such as heavy metals, nitrates, or most synthetic organic chemicals. ELGA shows that UV at 185 nanometers can help oxidize trace organic molecules, but even then these are removed by downstream ion exchange. For homeowners, this means 253.7 nanometer UV should be viewed as a microbiological barrier, not a comprehensive water purifier.

A simple way to think about it is summarized here.

For drinking water |

What 253.7 nm UV does |

What it does not do |

Microbes |

Inactivates bacteria, viruses, and many protozoa, including some chlorine‑resistant species, when properly dosed. |

Does not guarantee “sterility” or kill every last spore; does not prevent recontamination after treatment. |

Particles and turbidity |

Disinfects clear water very effectively when pre‑filtered. |

Does not remove dirt or sediment; effectiveness drops sharply in murky or highly colored water. |

Chemistry |

Disinfects without adding chemicals, residues, taste, or odor. |

Does not remove dissolved metals, salts, or most organic pollutants; does not change hardness or total dissolved solids. |

For a smart home hydration system, the sweet spot is clear, microbiologically risky water that has already been filtered but where you want robust, chemical‑free disinfection right before the point of use.

253.7 nm vs 222 nm Far‑UVC: When Each Makes Sense

In recent years, far‑UVC at 222 nanometers has received attention as a potentially safer form of germicidal UV for occupied spaces. It is important to understand how it compares to conventional 253.7 nanometer systems.

Technical and industry analyses, including work summarized by Emma Deng and consumer‑facing explanations from LivingStarPlus, draw a clear distinction. Lamps emitting at 222 nanometers typically use excimer technology and produce narrow‑band UV‑C in the far‑UVC range. Experiments suggest that this wavelength can inactivate many bacteria and viruses while being strongly absorbed in the outermost layers of the skin and the tear film of the eye, so it does not significantly penetrate to living cells. Research led by groups such as those at Columbia University has reported promising safety data over multi‑year observations under controlled exposure limits.

In contrast, 253.7 nanometer germicidal lamps are the classic low‑pressure mercury technology. They emit strongly in a band that penetrates more deeply into tissue and is known to damage skin and eyes with direct exposure. CDC summaries and multiple engineering sources state plainly that these conventional UVC wavelengths can cause eye irritation, photokeratitis, and erythema, and they are treated as an occupational hazard that must be mitigated through shielding, interlocks, and safe operating procedures.

Both wavelengths are germicidal. Coospider and HVAC industry sources describe 222 nanometer systems as effective for continuous air disinfection in occupied rooms, while 253.7 nanometer systems are described as high‑intensity tools for air handlers, upper‑room installations, closed cabinets, and water reactors where direct human exposure is controlled.

From a smart hydration perspective, the choice is straightforward. For enclosed water sterilizers and disinfection cabinets, 253.7 nanometer lamps remain the practical standard. They are well validated for water, widely available, and straightforward to engineer into closed stainless‑steel chambers where no UV reaches the user. Far‑UVC at 222 nanometers is more relevant for whole‑room air treatment and public spaces where occupants are present while the system runs.

A concise comparison looks like this.

Feature |

253.7 nm germicidal UVC |

222 nm far‑UVC |

Typical lamp technology |

Low‑pressure mercury vapor |

Excimer lamps |

Safety profile |

Can damage eyes and skin with direct exposure; usually used in enclosed or shielded systems. |

Considered safer for human exposure when properly limited, because it does not significantly penetrate living tissue. |

Main applications today |

Drinking water reactors, lab water, HVAC coils, disinfection cabinets, aircraft and hospital surface treatment. |

Continuous or frequent air and surface disinfection in occupied rooms such as offices, schools, and healthcare waiting areas. |

Role in home hydration |

Standard choice for enclosed UV water sterilizers and chamber‑based devices. |

Primarily relevant for whole‑room air quality rather than direct water treatment. |

Both technologies will likely grow, but if you are comparing UV options for your kitchen or whole‑home hydration system today, the products delivering meaningful water protection almost always rely on 253.7 nanometer lamps.

Safety and Material Considerations Around 253.7 nm Lamps

Effectiveness is only half the story. Safe and durable use of 253.7 nanometer lamps requires a bit of respect for how powerful they are.

CDC infection‑control summaries and UV safety reviews emphasize that conventional UVC can cause acute eye and skin injury. Short exposures can produce photokeratitis (sometimes called “welder’s flash”) and painful erythema. Long‑term exposure increases risk for skin cancer and cataracts. News‑Medical’s overview of UV risks and benefits also notes ozone generation and material degradation as concerns with some UV sources.

Because of this, professional guidelines recommend that people not be present in rooms when traditional UVC fixtures are operating, unless those fixtures are engineered specifically as upper‑air systems that shield occupants from the direct beam. In laboratory biological safety cabinets, UV lamps are interlocked so they cannot operate when the sash is open.

For home water systems, the safety story is much simpler. In well‑designed units, the 253.7 nanometer lamp sits inside a sealed stainless‑steel reactor, often within a quartz sleeve, and only water is exposed. There is no line of sight from the user to the UV source. That said, any maintenance that involves opening the housing should only be done with power disconnected and the lamp off, following manufacturer instructions.

Material compatibility is another consideration. Honeywell reports that when aircraft components such as seat fabrics, belts, and polycarbonate window covers were exposed to UVC doses far beyond realistic use, there was no loss of flame retardancy or structural strength, although some lightly colored materials showed yellowing after doses equivalent to many years of daily use. The company also notes that UVC effects on materials are dose‑dependent.

In water systems, the main materials directly exposed to 253.7 nanometer light are the quartz sleeve and the inner stainless‑steel or reflective surfaces of the reactor. These materials are chosen specifically for UV durability. However, scaling, biofilms, or organic deposits can accumulate on the quartz sleeve, blocking UV and reducing dose. Multiple sources, including Coospider and ELGA, recommend cleaning lamp sleeves on a regular schedule, often with alcohol wipes or manufacturer‑approved methods, and replacing lamps at defined end‑of‑life hours even if they still appear lit.

Older or different types of UV lamps can produce ozone, which is a respiratory irritant and can degrade rubber and plastic. CDC and News‑Medical safety notes mention this, and consumer‑oriented guidance recommends choosing “ozone‑free” models where possible. Honeywell specifically highlights that its 253.7 nanometer aircraft system does not generate ozone or leave chemical residues, so treated areas can be used immediately. Many modern low‑pressure 253.7 nanometer lamps used for water and air are designed to be ozone‑free.

In practical terms, for a homeowner using a UV water sterilizer, the key safety practices are straightforward. Choose a purpose‑built enclosed system for water rather than an open‑bulb room disinfection lamp. Follow installation and maintenance instructions, including lamp replacement intervals. Avoid looking at any bare UVC lamp when energized. And treat any product that claims germicidal action but simply glows purple with skepticism, since sources like Coospider point out that not all blue or violet light is actually germicidal.

Pros and Cons of 253.7 nm UV Lamps in Smart Home Hydration

Putting the evidence together, 253.7 nanometer UV brings a mix of strengths and limitations to home hydration systems.

On the plus side, it offers broad‑spectrum microbiological protection without chemicals. CDC, EPA, and water technology providers agree that UVC is effective against a wide range of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa, and that 253.7 nanometer low‑pressure mercury lamps are near the optimal germicidal wavelength. For homeowners, that translates into the ability to neutralize microbes that slip past filtration or that resist chlorine, without adding any taste, odor, or by‑products.

UV systems are compact and energy efficient. Drinking water guides emphasize that UV units do not require large contact tanks, and their power draw is modest compared with many other appliances. Once installed, operation is largely automatic, especially when combined with flow sensors or controls, and maintenance mainly consists of periodic lamp replacement and sleeve cleaning.

From a wellness perspective, UV is also attractive because it preserves the sensory and nutritional qualities of water and beverages. Food science work on UV‑treated juices and vegetable products finds that 253.7 nanometer UV can extend shelf life and improve microbiological safety while preserving heat‑sensitive vitamins better than thermal processing, when designed correctly. In drinking water, sources such as PureWater guidance point out that UV treatment leaves pH, taste, color, and odor unchanged.

On the downside, 253.7 nanometer UV is not a complete water solution by itself. It requires clear, pre‑filtered water to achieve its rated performance. It does not remove particles, discoloration, or dissolved chemicals, and it does not maintain a residual disinfectant in your plumbing. That means UV must be integrated with appropriate filtration and, in some cases, additional barriers if your source water carries chemical contaminants.

UV effectiveness is also dose‑sensitive. EPA and UVGI design guidance explain that systems must be sized for worst‑case conditions, including lamp aging, fouling, high flows, and low UV transmittance. In the home context, that translates into choosing a UV unit rated for your actual peak water demand and sticking to maintenance schedules. Ignoring lamp replacement because “the light is still on” is a real‑world failure mode that many safety bulletins warn about.

Finally, any system that uses conventional 253.7 nanometer lamps needs thoughtful safety design, even if the lamp is enclosed. Access panels, warning labels, and interlocks exist for a reason. When I advise families, I strongly favor systems from reputable manufacturers that provide clear documentation, third‑party certifications, and realistic performance claims based on UV dose and log reductions rather than vague promises.

How to Evaluate a 253.7 nm UV Lamp for Your Home Water

If you are considering a UV component for your smart hydration setup, a few evidence‑based checkpoints can help.

First, confirm the wavelength and lamp type. Product literature should explicitly state that the lamp emits in the UVC range near 254 or 253.7 nanometers and uses germicidal UV technology, not just “blue light.” Educational pieces from Coospider and Stouch Lighting both emphasize that only specific UVC wavelengths are germicidal and that not all purple or blue‑glowing lights in consumer devices provide meaningful disinfection.

Second, look at how the unit fits into a treatment train. EPA and ELGA both position UV after filtration. For a home system, that means sediment and carbon filtration or reverse osmosis should typically come before UV. If a UV unit is marketed as a stand‑alone solution for dirty or highly colored water, that is a red flag.

Third, pay attention to flow and dose. Technical guidance from UVGI and EPA describes dose as a function of lamp intensity, flow, and water quality, and utilities validate reactors to ensure that required log reductions are met at peak flows. While residential units are not usually validated to the same standard, credible manufacturers specify maximum flow rates and sometimes quote expected log reductions for defined conditions. Matching the unit to your home’s actual water demand, rather than overshooting its capacity, is central to real effectiveness.

Fourth, check for safety and quality features. Coospider’s buying advice for UV lamps suggests looking for timer controls, motion or occupancy sensors where appropriate, and certifications such as UL, CE, or similar marks that indicate the product has been tested. For water systems, I look for sturdy stainless‑steel housings, UV‑resistant quartz sleeves, and documentation of lamp life and maintenance procedures.

Finally, consider maintenance as part of the decision rather than an afterthought. CDC and manufacturer guidance recommend regular cleaning of lamp surfaces or sleeves and scheduled lamp replacement, because UVC output declines well before visible light does. Choose a system where replacement parts are available, instructions are clear, and maintenance feels manageable for your household or service provider.

When these elements line up, a 253.7 nanometer UV stage can quietly become one of the most important layers in your home hydration safety net.

Brief FAQ

Do 253.7 nm UV lamps make any water safe to drink?

No. 253.7 nanometer UV lamps are powerful tools for inactivating microorganisms, but they are not magic. UV disinfection is designed for reasonably clear water where the main concern is microbiological, not for heavily polluted or chemically contaminated sources. UV does not remove heavy metals, nitrates, industrial chemicals, or salt, and its performance drops sharply in very turbid or colored water. For safe hydration, UV must be combined with appropriate filtration and, where necessary, other treatments matched to your specific water quality.

Can 253.7 nm UV replace boiling or chlorination?

In terms of inactivating many waterborne pathogens, properly dosed 253.7 nanometer UV can equal or exceed traditional thermal or chemical methods, and EPA gives UV full disinfection credit for hard‑to‑kill protozoa in drinking water plants. However, UV does not provide a disinfectant residual, whereas chlorination leaves a small amount of active disinfectant in the distribution system. For a home, this means UV can be an excellent final disinfection step for water that is already reasonably clean, but it is not a drop‑in replacement for multi‑barrier strategies in high‑risk settings.

Will a 253.7 nm UV system help with COVID‑19 risk at home?

Laboratory work summarized by Honeywell and UVGI researchers shows that 253.7 nanometer UVC can inactivate SARS‑CoV‑2 on surfaces at doses achievable with engineered systems, with reductions of around 99 percent in controlled tests. That said, everyday COVID‑19 risk is dominated by person‑to‑person respiratory transmission, and real‑world performance depends on airflow, room use, and other measures. In a home hydration context, a UV water system can ensure that your drinking water is not a vector for microbes, but it should be seen as part of broader indoor air quality and infection‑control strategies rather than a stand‑alone pandemic solution.

Closing Thoughts

Thoughtfully applied, 253.7 nanometer UV is one of the most powerful, evidence‑backed tools we have for protecting water, air, and surfaces from microbial contamination without chemicals. In a smart home hydration system, it works best as a quiet specialist: a final, well‑engineered barrier that complements good filtration and sound plumbing. When dose, water quality, safety, and maintenance are respected, a 253.7 nanometer lamp can help you pour a glass of water that is not only refreshing, but also backed by the same science trusted in hospitals, aircraft, and advanced food production.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultraviolet

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10486447/

- https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/disinfection-sterilization/miscellaneous-inactivating-ingredients.html

- https://www.lincolntech.edu/news/skilled-trades/hvac/separating-fact-from-myth-on-hvac-uv-light-benefits

- https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-06/documents/uv.pdf

- https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/technical%20resources/covid-19/si_s16_ch17.pdf

- https://www.news-medical.net/whitepaper/20181112/Ultraviolet-Radiation-Risks-and-Benefits.aspx

- https://us.elgalabwater.com/technologies/ultraviolet

- https://www.linkedin.com/posts/roshan-chawake-0a9434182_why-is-2537-nm-uv-sterilization-is-activity-7350962445877686272-jk_F

- https://livingstarplus.com/uvc-wavelength-253nm/?srsltid=AfmBOoqTUrPVYegRnl2vg3khV1pJA9PM_zsqwRoSzqN8W60tJxklJuL5

Share:

How Capacitive Touch Control in Smart Faucets Achieves Water Resistance

Understanding the Minimum Pressure Requirement for RO Systems