As a smart hydration specialist, I see the same question come up every pickling season: “Can I use my reverse osmosis water for pickles, or will it ruin the batch?” Behind that question are real concerns about safety, texture, and the investment you already made in your home RO system.

The good news is that, used thoughtfully, reverse osmosis (RO) water can be an excellent choice for both quick vinegar pickles and slow, fermented vegetables. The key is understanding what RO water does to your brine chemistry and how that interacts with the food science behind safe, high‑quality pickles.

In this guide, I will walk through the science, the pros and cons, and practical step‑by‑step advice grounded in extension publications, food science research, and water treatment expertise.

Why Water Quality Makes Or Breaks Your Pickles

Pickling is all about using acidity and salt to control microbes. According to extension guidance from Oregon State University, high acidity in the jar prevents growth of Clostridium botulinum and most spoilage organisms. You can reach that acidity two ways: by letting lactic acid bacteria ferment vegetables in a salted brine, or by adding enough 5 percent vinegar to create a quick pickle.

Water shows up in every part of that process. It rinses your produce, dissolves your salt and sugar, dilutes your vinegar, and fills the gaps in the jar. A research brief from a sustainability publication on home canning and pickling notes that water quality is crucial for both safety and quality. Hard water with high mineral content can cause cloudy brine and soften vegetables, while water contaminated with microbes or heavy metals can compromise the safety of canned or pickled foods.

Extension publications on pickling from Oregon State University and North Dakota State University add more detail. They recommend: using soft water or pre‑boiled, settled water in brines; following laboratory‑tested recipes exactly; never reducing the amount of vinegar or increasing the amount of water in a recipe; and discarding jars with signs of spoilage such as mold, gas bubbles, or off‑odors. Those same sources flag that minerals in hard water and anti‑caking additives in table salt can cloud a brine and alter texture.

Industrial guidance echoes this. A piece on water efficiency in pickling and fermentation for processors underscores that water is the solvent that carries the acids and salts that preserve and flavor foods, and that water quality directly affects taste, texture, safety, and even regulatory compliance.

When you put all of this together, you get a clear picture: water is not a neutral background ingredient. It is part of the preservation system. That is why choosing RO water, or any treated water, deserves a closer look rather than a simple yes or no.

What Reverse Osmosis Water Actually Is

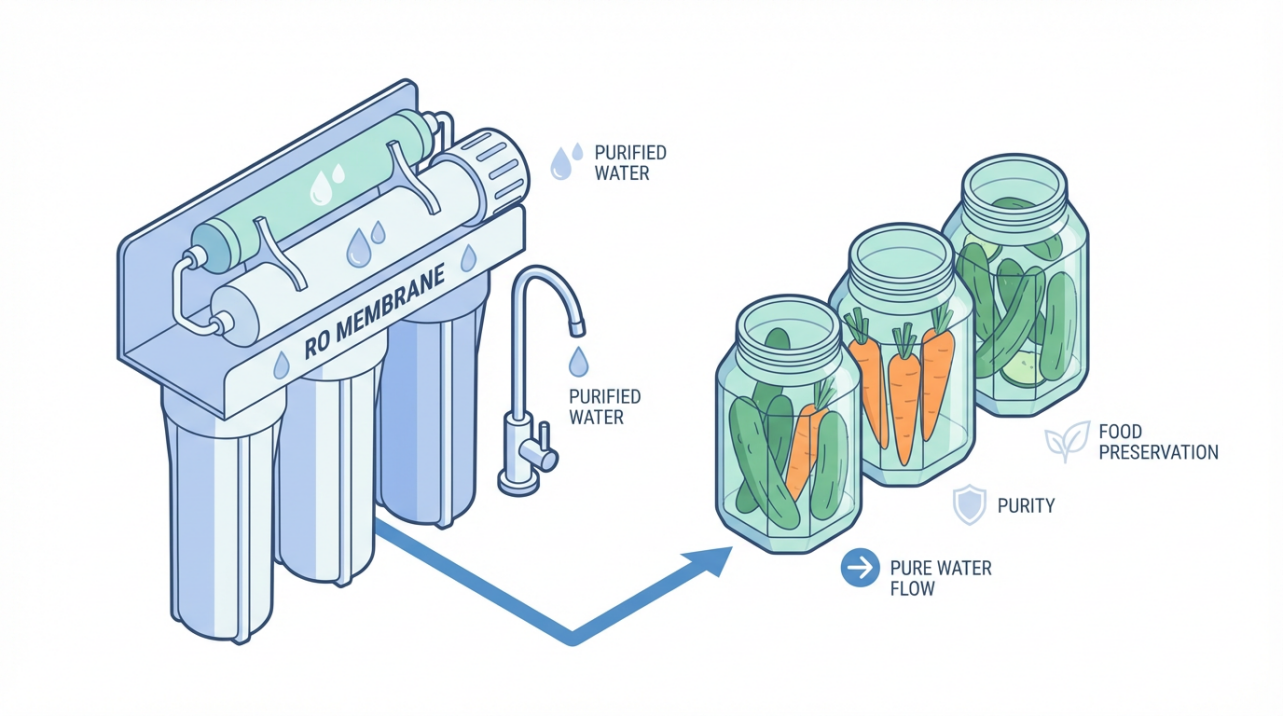

Reverse osmosis is a membrane‑based purification process used in homes, greenhouses, and food processing plants. In simple terms, osmosis naturally moves water through a membrane from a lower solute concentration to a higher one until both sides are balanced. Reverse osmosis flips that script. By applying pressure to the more concentrated side, water is forced through a semi‑permeable membrane toward the cleaner side, leaving most dissolved substances behind.

Greenhouse water treatment articles describe modern RO membranes as trapping particles and impurities down to about 0.0009 micron. Residential and light commercial systems typically remove around 90 to 99 percent of common dissolved contaminants, including many heavy metals, nitrates, some PFAS, pesticides, and a large share of total dissolved solids. They also work in tandem with carbon prefilters that strip out chlorine, many disinfection by‑products, and much of the odor‑ and taste‑causing chemistry in tap water.

Because so many ions are removed, RO permeate (the treated water) has very low mineral content and a very low total dissolved solids reading. Articles for growers and home users note that pure water like this barely conducts electricity, which is a practical way to see how low the mineral load is. Coffee and culinary guides point out that plain RO water often has a slightly acidic pH around 6 to 6.5, mainly because buffering minerals such as calcium and magnesium have been removed.

Many drinking‑water focused RO systems now add a remineralization stage. Companies that build these systems describe this as passing the RO water through an alkaline filter that dissolves a small amount of calcium, magnesium, or similar minerals back into the water. That remineralized RO water tends to taste fuller and less “flat,” and its pH moves back toward a mild alkalinity, which many people prefer for drinking.

The bottom line is that RO water is very consistent, low‑contaminant, low‑mineral water.

That profile is excellent for controlled cooking and brewing, but some home fermenters worry it is “too pure” for living, microbial processes like pickling. To answer that, we need to talk about how fermentation actually works.

RO Water And Fermented Pickles

Fermented pickles, sauerkraut, kimchi, and similar foods rely on naturally occurring lactic acid bacteria. A homesteading article on fermenting cabbage and other vegetables defines lacto‑fermentation as the process where these bacteria break down sugars into lactic acid and carbon dioxide in a low‑oxygen, salty environment. That lactic acid gradually lowers the pH of the brine, preserving the vegetables and creating their distinctive sour flavor.

In these ferments, water matters in two main ways. First, it dissolves salt, creating the brine that suppresses unwanted microbes. Second, its chemistry can either help or hinder the beneficial bacteria.

The same homesteading source explicitly recommends non‑chlorinated water for vegetable ferments and gives distilled or reverse‑osmosis water as good options. The reason is simple: chlorine can kill or stress beneficial bacteria. When you hydrate your cabbage or cucumbers with chlorinated water, you are asking your “good” microbes to start the race a few steps behind. Using dechlorinated, RO, or distilled water removes that stress.

Likewise, a research‑based discussion about sourdough starters notes that the idea that RO water is “bad” for fermentation is not supported by available evidence. Minerals in water are compared to “starter vitamins”: helpful but not essential. Starters can ferment actively in low‑mineral water as long as the flour, environment, and feeding schedule are appropriate.

Taken together, these points translate well to vegetable ferments. The main drivers of fermentation success are:

- The salt concentration of the brine. Literature surveys show typical vegetable ferments often use around 1.5 to 2 percent salt by weight, with a broader safe range up to about 5 percent for some styles. A practical homestead guideline is about 1 to 2 teaspoons of non‑iodized salt per cup of water, adjusted depending on the wateriness of the vegetables.

- Keeping vegetables fully submerged under brine. Oregon State University recommends that fermented vegetables stay 1 to 2 inches under the brine, held down by a plate or a food‑grade weight, to maintain an anaerobic zone where lactic acid bacteria can thrive.

- Using food‑grade crocks, glass, or appropriate plastic containers. OSU cautions against zinc, copper, brass, galvanized, or iron equipment, which can react with salt and acid and affect both quality and safety.

None of these core principles depend on the mineral content of the water. In fact, because RO water removes interfering chemistry like chlorine, iron, and some other reactive metals, it can make your fermentation environment more predictable.

Microbiota research from a pickling study published in a food science journal reinforces how central salinity, oxygen levels, and time are. That work compared the microbial communities and metabolites in salted leafy vegetable pickles under different process conditions. It found that safe lactic acid fermentation was associated with moderate salinity, low pH, and anaerobic conditions that favor lactic acid bacteria. High‑salt, long‑term salt stock brines, by contrast, selected for halophilic bacteria and very different metabolites. The key variables were salt and process design, not the trace mineral profile of the water.

From a practical standpoint, using RO water for fermented pickles is not only acceptable but can be beneficial, as long as you: use the correct salt concentration, keep vegetables submerged, use food‑grade containers, and follow the rest of the fermentation best practices from extension services.

RO Water And Quick Vinegar Pickles

Quick pickles, sometimes called “fresh pack” or “refrigerator” pickles, reach safe acidity by adding vinegar rather than waiting for fermentation. Extension guidance outlines two main styles: brined and fermented pickles that sit for weeks at room temperature, and quick, unfermented pickles that are ready in a day or two. The quick style depends on adding enough 5 percent commercial vinegar to the recipe and then heat‑processing the jars in a boiling‑water canner or similar setup.

In this case, the safety rules are explicit. Oregon State University instructs home canners to: follow laboratory‑tested recipes exactly; never reduce the amount of vinegar; never increase the amount of water; and use only 5 percent commercial vinegar, never homemade. North Dakota State University’s tested cucumber pickle recipe gives a representative formulation that uses measured amounts of pickling salt, sugar, and 5 percent vinegar in a specified volume of water, then calls for proper headspace and processing.

Substituting RO water for tap water in these recipes does not change the amount of vinegar or the overall acid load. Since plain RO water is usually slightly more acidic than typical tap water, the change is in the conservative direction. What you must not do is treat RO water as a reason to relax on recipe ratios. The vinegar concentration and water volume still must match the tested formula, regardless of how “pure” the water is.

Where RO water clearly helps quick pickles is in quality.

Hard water minerals and anti‑caking agents in common table salts are well‑known causes of cloudy brine and soft texture. Extension bulletins specifically recommend using pickling or canning salt, not reduced‑sodium salt for brined pickles and sauerkraut, because reduced‑sodium blends can change flavor and are not suitable for slow ferments. When the water is soft and low in minerals, brines stay clearer and vegetables are less likely to pick up off‑flavors from the water itself. That aligns with broader RO‑and‑cooking articles that report cleaner, more accurate flavors in soups, stocks, rice, and beans made with RO water instead of hard or chlorinated tap.

Taste, Texture, And Color: What To Expect With RO Water

Most of the flavorful and colorful chemistry in pickles comes from the vegetables, spices, and vinegar or lactic acid. Water can help those shine, or it can partially mask or distort them.

Drinking‑water and cooking‑focused RO guides describe several consistent sensory effects. For hot drinks like coffee and tea, which are more than 95 percent water, RO water removes chlorine, sulfur notes, and metallic tastes that can cause bitterness or muddiness. The result is a “cleaner,” more transparent flavor where subtle notes are easier to perceive. Kitchen articles on cooking with RO water report similar improvements in stocks, soups, and grains, where off‑tastes from tap water used to compete with seasonings and fresh ingredients.

Translating that to pickling, you can expect:

- Clearer, brighter brines when you use RO water and pickling salt instead of hard, mineral‑rich water and table salt with additives. This matches extension observations that hard water clouds brines and softens vegetables.

- More “true” herb and spice flavors. When chlorine and some reactive metals are removed, dill, garlic, mustard seed, peppercorns, and other seasonings are not competing with background bitterness or odd aromas from the water.

- Less risk of softening from water chemistry. While overall crispness depends more on produce quality, salt level, and methods like ice‑water soaking or careful use of pickling lime, taking excess hardness out of the equation removes one common cause of texture problems.

One caution comes from the general RO cooking literature rather than pickle‑specific studies. Some bakers and chefs notice that very low‑mineral water can change the behavior of doughs and some sauces, because minerals influence gluten and certain chemical reactions. However, those processes are far more sensitive to pH and minerals than a vinegar‑dominant or salt‑dominant pickle brine. For pickling, the acidic or salty environment and the vegetable cell structure are the dominant factors; the small shift from low‑mineral to moderate‑mineral water is typically much less important.

Pros And Cons Of Using RO Water For Pickling

Because I look at both water treatment and food science, I like to lay out the trade‑offs clearly. The table below summarizes how RO water compares to typical tap water choices for home pickling.

|

Aspect |

Typical chlorinated tap water |

Hard well water |

Reverse osmosis water (plain or remineralized) |

|

Chlorine / disinfectants |

Often present; can add off‑flavors; may stress ferment microbes |

Often absent but may have other issues |

Removed by RO prefilters; good for fermentation flavor and microbes |

|

Mineral hardness |

Varies; moderate hardness can cloud brine |

Often high; known to cloud brine and soften vegetables |

Very low; brines tend to stay clear; texture more consistent |

|

Heavy metals / contaminants |

May contain lead, nitrates, or others depending on plumbing and source |

Possible contaminants from aquifer or plumbing |

Many contaminants reduced 90–99 percent in properly maintained systems |

|

Taste and aroma |

Can impart chlorine, sulfur, or metallic notes |

Can impart mineral or metallic notes |

Neutral taste; lets vegetable and spice flavors dominate |

|

Fermentation reliability |

Chlorine and some chemistry can slow or inhibit lactic acid bacteria |

Hardness less of a problem than chlorine |

Non‑chlorinated, low‑contaminant water favors beneficial microbes when salt and process are correct |

|

Environmental footprint |

No added waste beyond local supply use |

Depends on source and treatment |

RO systems typically waste several gallons of concentrate for each gallon of product water, though newer designs are more efficient |

From a strictly culinary and safety standpoint, RO water has strong advantages: cleaner flavor, more predictable chemistry, no chlorine, and sharply reduced contaminants.

The main drawbacks are not about the pickles themselves but about the system: wastewater during treatment, cost and maintenance of filters and membranes, and the fact that RO water can be aggressive toward some plumbing metals, which is why technical articles advise against sending RO water through galvanized or copper pipes.

Practical Guidelines: Using RO Water In Your Pickling Routine

Theory is useful, but your jars still have to seal and your pickles still have to crunch. Here is how I recommend using RO water in real, home‑kitchen pickling, aligned with extension and research‑based guidance.

Prepare Your RO System And Your Recipe

Before the first batch of the season, make sure your RO unit is in good condition. Water treatment and holiday cooking articles stress the importance of timely filter and membrane changes, usually every 6 to 12 months for prefilters and every 2 to 5 years for membranes, depending on usage and water quality. A neglected RO system can harbor bacteria in the filters and produce water that is less clean than you expect.

Choose a laboratory‑tested pickling recipe from a reliable source such as a university extension service. Check that the vinegar is 5 percent acidity, that the salt specified is canning or pickling salt, and that the processing times and headspace instructions are clear. Do not change the vinegar‑to‑water ratio, even if you are using RO water.

Using RO Water For Quick Vinegar Pickles

When making quick pickles, use RO water anywhere the recipe calls for water. Wash and trim vegetables exactly as directed; for cucumbers, extension recipes stress removing a thin slice from the blossom end, which can contain enzymes that soften pickles. Soaking cucumbers in ice water for several hours before packing is a tested method from Oregon State University for improving crispness. This step is independent of water type, and you can use RO ice or cold RO water for the soak if you wish.

Prepare the brine by combining vinegar, RO water, pickling salt, and any sugar or spices in a non‑reactive pot. Heat it to a full boil as the recipe directs. Pack hot or raw vegetables into hot jars, maintaining about half an inch of headspace, and cover them with hot brine to the same headspace level. Remove trapped air bubbles with a non‑metal utensil, clean jar rims, apply new two‑piece lids, and process in a boiling‑water canner or via a lower‑temperature pasteurization method if the tested recipe allows it.

Once processed, let jars cool undisturbed, check seals, remove screw bands for storage, label the jars, and store them in a cool, dark, dry place.

Several extension bulletins recommend allowing 4 to 5 weeks before opening for best flavor development. None of these steps need to change because you used RO water; the role of RO is simply to give you a clean, predictable base that does not fight the vinegar and spices.

Using RO Water For Fermented Pickles And Sauerkraut

For fermented vegetables, start with fresh, unblemished produce. Clean glass jars, food‑grade crocks, or suitable plastic fermentation vessels are all acceptable, while metal containers made of zinc, copper, brass, galvanized steel, or iron are not, because they can react with salt and acid.

Mix your brine using RO water and non‑iodized salt without anti‑caking agents. A practical range drawn from fermentation guides is around 1.5 to 2 percent salt by weight for many vegetables, which corresponds loosely to about 1 to 2 teaspoons of salt per cup of water, with adjustments based on vegetable type and water content. The key is staying in a salinity range that slows spoilage organisms but still allows lactic acid bacteria to flourish.

Pack vegetables in the vessel and pour the RO‑based brine over them, making sure they are completely submerged. Use a clean plate, glass weight, or a food‑grade weight system to keep the vegetables at least an inch below the brine surface. Cover the vessel with a clean towel or lid that can vent gas, or use a dedicated fermentation lid with an airlock to let carbon dioxide escape while keeping air and insects out.

During fermentation, keep the container reasonably cool and out of direct sunlight. The homesteading article notes that fermentation continues over time and quality declines if ferments sit warm for too long, even though some refrigerated ferments can last many months. Check daily to ensure vegetables stay submerged and to observe gas bubbles, which indicate active fermentation.

Because RO water is non‑chlorinated, it will not inhibit lactic acid bacteria the way untreated chlorinated tap water can. You still must monitor for spoilage. Oregon State University advises discarding any jars or batches with mold growth on the brine surface, off‑odors, unusual cloudiness not typical of that recipe, or vigorous bubbling that continues far beyond the expected fermentation window.

When Might You Skip RO Water For Pickling?

Despite its culinary and safety advantages, RO water is not mandatory for successful pickling. There are situations where using it may not be the best choice.

Water treatment case studies and consumer comparisons highlight that standard residential RO systems often waste several gallons of concentrate for each gallon of purified water, with some reports citing ranges from about three to as high as twenty gallons wasted per gallon produced in certain configurations. If you live in a drought‑prone area or are trying to minimize water use, relying on RO for large kettles of brine may not align with your sustainability priorities unless your system is a high‑efficiency design.

Articles comparing home RO systems with spring water delivery also emphasize the upfront and maintenance costs of RO: installation, possible plumbing modifications, and ongoing filter and membrane replacements. If your tap water is already soft, neutral‑tasting, low in chlorine, and has been tested to show no concerning contaminants, the incremental benefit of RO for quick vinegar pickles may be relatively small.

RO water also can be aggressive toward certain plumbing materials, particularly galvanized and copper piping, as noted in greenhouse industry guidance. Most kitchen RO drinking taps and the glass jars you use for pickling are designed to handle low‑mineral water, but it is another reminder that RO is a tool that should be applied thoughtfully rather than by default.

Finally, if your RO system is overdue for maintenance, do not assume its water is “safer” for pickling than well‑maintained tap water. A neglected RO unit with exhausted filters can become a microbial reservoir. In that case, it is better to service the RO system first or temporarily follow extension guidance on using boiled and settled tap water or other appropriate treatments.

Short FAQ: Common Questions About RO Water And Pickling

Can RO water make pickles mushy?

Mushy pickles are usually caused by overripe or damaged vegetables, incorrect processing, enzymes from the blossom end of cucumbers, or recipe changes such as using the wrong type of salt or vinegar strength. Extension sources point to produce quality, blossom‑end enzymes, and process control as the main culprits. Hard water minerals can also soften texture over time. RO water removes hardness and does not introduce new softening factors, so it is not a typical cause of mushy pickles when recipes and procedures are correct.

Do I need to add minerals back into RO water for fermentation?

Available research on fermentations such as sourdough starters indicates that low‑mineral or demineralized water does not stop yeast and bacteria from thriving. Minerals help to some extent but are not essential. The homesteading fermentation guide specifically recommends distilled or reverse‑osmosis water to avoid chlorine, without suggesting mineral supplementation. For vegetable ferments, it is far more important to control salt concentration, temperature, and oxygen exposure than to adjust water mineral content. If you already own an RO system with a remineralizing filter for taste, you can use that water too, but extra mineral additions are not required for a healthy fermentation.

Can I use distilled water instead of RO water for pickling?

Yes, as long as the distilled water is potable and handled hygienically. From a pickling perspective, both distilled and RO water are very low in minerals and chlorine. The fermentation guide that recommends non‑chlorinated water treats distilled and RO as equally suitable options. The same safety rules still apply: follow tested recipes for vinegar strength and water volume, and do not alter acid or salt levels.

Does RO water alone make vegetables safe to store without vinegar or salt?

No. This is a critical safety point. Reverse osmosis removes many contaminants and off‑flavors, but it does not make low‑acid foods shelf‑stable by itself. Extension publications are clear that pickling safety comes from creating a high‑acid, properly salted environment and, for shelf‑stable products, heat‑processing jars for the specified time. Using RO water can improve the quality and consistency of your brines, but it is not a substitute for vinegar, salt, or proper canning technique.

Ending on a practical note, I encourage you to think of your RO system as a smart tool in your food‑preservation toolkit rather than a mysterious variable. When paired with trusted extension recipes and good produce, RO water can give you cleaner flavors, clearer brines, and more predictable ferments. That is exactly the kind of intersection between smart hydration and home food wellness that is worth embracing.

References

- https://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/pnw-355-pickling-vegetables

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8034358/

- https://www.ndsu.edu/agriculture/extension/publications/food-preservation-making-pickled-products

- https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/60701000/Pickle%20Pubs/p223.pdf

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/jf00102a017

- https://www.alamowatersofteners.com/the-pros-and-cons-of-cooking-with-reverse-osmosis-water/

- https://www.aqua-wise.com/post/why-it-s-important-to-cook-with-reverse-osmosis-water

- https://awqinc.com/reverse-osmosis-and-thanksgiving-cooking-why-pure-water-makes-a-difference/

- https://insights.spans.co.in/water-efficiency-in-pickling-industry-and-fermentation-processes-cm1mmd4j0001xtpnfrwl4j8da/

- https://aquasureusa.com/blogs/water-guide/benefits-of-ro-water-foods-and-drinks-that-taste-better?srsltid=AfmBOorhbyRLVXdp7uyLBXLoHb9Vv0CDzcm0xT_coYfkBIA4mQF4dJfi

Share:

Understanding the Adhesion Phenomenon in Milk Powder Solutions

Using Purified Water for Aquarium Water Changes Safely