Reverse osmosis has moved from industrial desalination plants to under‑sink systems in small European apartments. As a Smart Hydration Specialist and Water Wellness Advocate, I regularly see the same tension play out in homes, labs, and utilities across Europe: people love the ultra‑pure water, but they are nervous about leaks, environmental impacts, and whether their system actually complies with European rules.

Leak protection is where all of those concerns meet. In Europe, it is not just about keeping your kitchen floor dry. It is about safeguarding public drinking water networks, protecting rivers and seas from saline and chemical releases, and ensuring that high‑pressure, high‑energy RO systems operate safely for their entire life.

This article unpacks how European standards and regulations shape leak protection in RO systems, and how you can turn that framework into practical design and maintenance choices at home or in a commercial plant.

Europe’s Growing Dependence on RO – And Why Leaks Matter More Here

The European Commission’s Blue Economy Observatory describes desalination as a key water‑supply technology for water‑stressed coastal and island regions. Drawing on datasets from the Spanish desalination association AEDyr and the DesalData database, they report more than eleven thousand seven hundred desalination facilities operating worldwide, representing most of the global desalination capacity. Reverse osmosis, using polymer membranes, underpins the vast majority of these plants, especially in Europe’s Mediterranean region.

At the same time, a European Union LIFE project on RO membranes notes that reverse osmosis systems already accounted for the bulk of membrane‑based desalination by the early 2000s, with the market growing from about $1,400,000,000.00 in 2000 to about $3,800,000,000.00 in 2008. That growth has only intensified under climate‑driven drought pressure.

When that much of your water security depends on membranes, leaks are not a small nuisance. A leak in a large plant can release brine, chemicals, or partially treated wastewater into sensitive rivers and coastal zones. Research cited by the Blue Economy Observatory highlights how desalination brine can affect benthic ecosystems and coastal marine communities, which is one reason Europe’s environmental directives put such stress on controlling discharges and avoiding uncontrolled releases.

At the household scale, leaks are just as impactful in more personal ways. Work from the University of Nevada, Reno Extension explains that a typical residential RO system may need about two to four gallons of feed water to produce one gallon of drinking water. If that system quietly leaks into a cupboard or under a sink, your water waste and risk of mold, rot, and structural damage compound very quickly.

Several European sources also stress that RO is not banned, but it is scrutinized. A technical brief on the “main problems with RO systems” explains that there is no blanket prohibition on RO water in Europe. Instead, the European Union’s Drinking Water Directive and some national policies emphasize maintaining certain mineral levels and limiting water waste. Countries such as Germany and France often favor technologies that retain minerals for public supply, while RO is used more selectively. That context is important: RO systems are allowed, but they are expected to be well‑designed, well‑maintained, and environmentally responsible, including how they handle leaks.

The Regulatory Backbone Shaping Leak Protection

European rules rarely say “install this exact leak sensor in your RO system.” Instead, they define outcomes for health, safety, and the environment. Leak protection is the practical way you meet those outcomes.

Drinking Water Quality and Materials Safety

Within the European Union, the Drinking Water Directive sets strict quality requirements for water intended for human consumption. A related framework in the United Kingdom, overseen by the Drinking Water Inspectorate, mirrors this focus on high microbiological and chemical safety. For RO, this means that the treated water must consistently meet potable‑water standards, and the system must not create new contamination routes.

On the materials side, European food‑contact law is clear. EU legislation on materials and articles in contact with food, along with national regulations such as the UK’s Materials and Articles in Contact with Food Regulations, requires that polymers, adhesives, and sealants in contact with beverages cannot transfer harmful substances or alter taste and odor. A technical article on UK and EU frameworks for RO notes that these rules apply to membranes, housings, and other wetted parts when RO water is used as an ingredient in food or drink manufacture.

A poorly sealed housing, cracked fitting, or o‑ring leak is therefore more than a cosmetic problem. It can create stagnant pockets where bacteria grow, allow non‑approved materials to contact product water, and make it harder to demonstrate compliance with drinking‑water and food‑contact requirements.

Protecting the Public Drinking Water Network

In the United Kingdom, the Water Supply (Water Fittings) Regulations govern how equipment, including RO systems, is connected to mains water. They require consent from the local water supplier and robust backflow prevention so contaminants from any downstream process cannot siphon or push back into the public distribution system.

While these regulations are UK‑specific, they illustrate a European mindset: cross‑connections and backflow are treated as serious risks. An incorrectly installed RO system can create exactly that sort of risk if it leaks, if check valves fail, or if a drain connection is improperly made. When I review installations in European homes and commercial kitchens, I pay close attention to air gaps, non‑return valves, and any sign that a leak could compromise backflow protection.

Environmental and Brine‑Management Rules

On the environmental side, several European directives govern what leaves an RO plant:

- The Water Framework Directive sets overarching goals for good ecological and chemical status in surface and groundwater.

- The Marine Strategy Framework Directive focuses on protecting marine waters.

- The revised Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive tightens requirements for wastewater collection and treatment, including in coastal communities.

A legal overview of RO brine disposal explains that these instruments require environmental impact assessments, site‑specific discharge conditions, and, in many cases, the use of mixing zones and circular‑economy measures such as resource recovery and brine valorization.

In practical terms, if you operate an RO system that discharges brine or treated wastewater, any leak that bypasses the regulated discharge route becomes a compliance issue. A cracked concentrate pipeline under a slab or an overflowing neutralization tank is not just a maintenance headache; it can violate permits and damage ecosystems. European regulators may not prescribe exact leak‑detection technologies, but they do expect operators to keep pollutants inside the treatment train until they reach controlled discharge points.

Chemical, Electrical, and Pressure Safety

RO plants bring together chemical dosing, high pressures, and electrical equipment. Several European and UK rules intersect here:

- REACH (and its UK counterpart) applies to chemicals and polymeric articles in RO systems. Operators must know which hazardous substances are present and manage associated risks.

- The Biocidal Products Regulation covers biocides used in RO cleaning or preservation, requiring approved active substances and authorized products.

- Electrical safety is governed by frameworks such as the Electricity at Work Regulations in the UK and harmonized product directives in the EU.

- High‑pressure components fall under Pressure Systems Safety Regulations and must be designed, inspected, and maintained to prevent failures.

Leaks sit right in the middle of all this.

A pinhole leak on a high‑pressure line can erode metal, spray atomized water near live electrical cabinets, and slowly worsen until it becomes a rupture. A chemical dosing leak can expose staff and corrode structural steel. These are exactly the kinds of combined hazards that European safety law is designed to minimize.

Circular Economy and Membrane Waste

European policy also increasingly views RO through a circular‑economy lens. A ScienceDirect article on sustainability in RO membrane waste management notes that, following a linear “take–make–consume–dispose” pattern, end‑of‑life RO membranes used for five to ten years are often landfilled. Based on that lifespan, about thirty thousand metric tons of waste membranes were expected worldwide by 2025, which equates to roughly sixty‑six million pounds of polymer material.

The European Union has endorsed a waste hierarchy that prioritizes reduction, reuse, and recycling over energy recovery and landfill. A LIFE project called REMEMBRANE demonstrated that about eighty percent of end‑of‑life membranes in a Spanish desalination plant could be recovered and reused, often at less than half the cost of new elements. Both that project and the ScienceDirect study highlight how reuse, conversion into lower‑pressure membranes, and recycling of polymer parts can dramatically reduce environmental burdens.

Designing RO systems so membranes last longer, can be removed without damage, and do not suffer premature failure from fouling or mechanical stress is therefore part of responsible leak and risk management in a European context. A chronically leaking system that corrodes housings, over‑pressurizes elements, or forces frequent replacement runs directly against those circular‑economy objectives.

What Counts as a “Leak” in an RO System?

In everyday language, a leak is water where it does not belong. In RO systems, there are two broad kinds of leaks to think about: physical leaks from the plumbing, and “micro‑leaks” in the barrier function of the membrane itself.

Physical Leaks in Household and Building Plumbing

A detailed guide from NU Aqua, a residential RO supplier, shows how many small things can go wrong under a sink or in a utility room. Leaks often appear at filter housings due to loose fittings, worn o‑rings, or hairline cracks. Faucets can drip when washers and gaskets wear out, creating puddles at the base. Push‑fit tube connections leak if the tubing is not fully seated or if the locking clip is missing. Feed‑water adapters can seep around poorly sealed threads unless wrapped carefully with Teflon tape.

A separate troubleshooting guide from Parker & Sons emphasizes three root causes for tank and line leaks: excessively high water pressure, poor installation, and normal wear and tear on components. High pressure can force water past seals or burst lines; improper tightening of fittings can create micro‑gaps; aging o‑rings harden and lose elasticity.

Maintenance‑focused content from Realtruetek adds that poor filter and membrane hygiene compounds leak risk. Sediment buildup and chlorine attack can degrade housings and seals, while biofilms on surfaces can hide small leaks and eventually produce noticeable taste and odor changes.

From a standards perspective, none of this is exotic; it is exactly the sort of thing basic plumbing codes aim to prevent.

A leak‑test specification from a large U.S. institution, for example, defines leak testing as pressurizing a piping system with water or air, holding it for a set time, and confirming there is no visible leakage and no unacceptable pressure drop before the system is concealed or insulated. European inspectors and installers apply similar principles, even if the specific test pressures and documentation requirements differ.

Micro‑Leaks Through Membranes and Fittings

Leak protection at the membrane level is more subtle. A peer‑reviewed article in the journal Desalination by Niewersch and co‑authors describes how reverse osmosis membranes can be modeled as a combination of intact material and discrete imperfections or defects. Within a solution–diffusion–imperfection framework, they use mechanistic transport equations and nonlinear optimization to quantify how water and salts move through both the ideal membrane and any imperfections.

From a safety standpoint, that work is motivated by drinking‑water and reuse regulations that require high log‑removal of viruses and protozoa. The article reviews U.S. Environmental Protection Agency guidance and ASTM standards for membrane integrity testing, along with experimental studies using bacteriophage surrogates such as MS2 and Qβ. It shows how even very small imperfections can compromise the barrier if not detected.

Europe’s Regulation on minimum requirements for water reuse, Regulation (EU) 2020/741, fits into the same story. Although the research note we have only infers its details from the broader literature, it underscores that the regulation defines water‑quality classes, risk‑management obligations, and monitoring requirements for reclaimed urban wastewater used in irrigation. In practice, that means operators must demonstrate that their membranes and other barriers are intact and that no “leakage” of pathogens or chemicals is occurring through micro‑defects or bypasses.

When I evaluate RO systems that feed high‑purity uses—whether that is drinking water, food production, or advanced reuse—I treat membrane integrity as a form of leak protection just as important as keeping water off the floor.

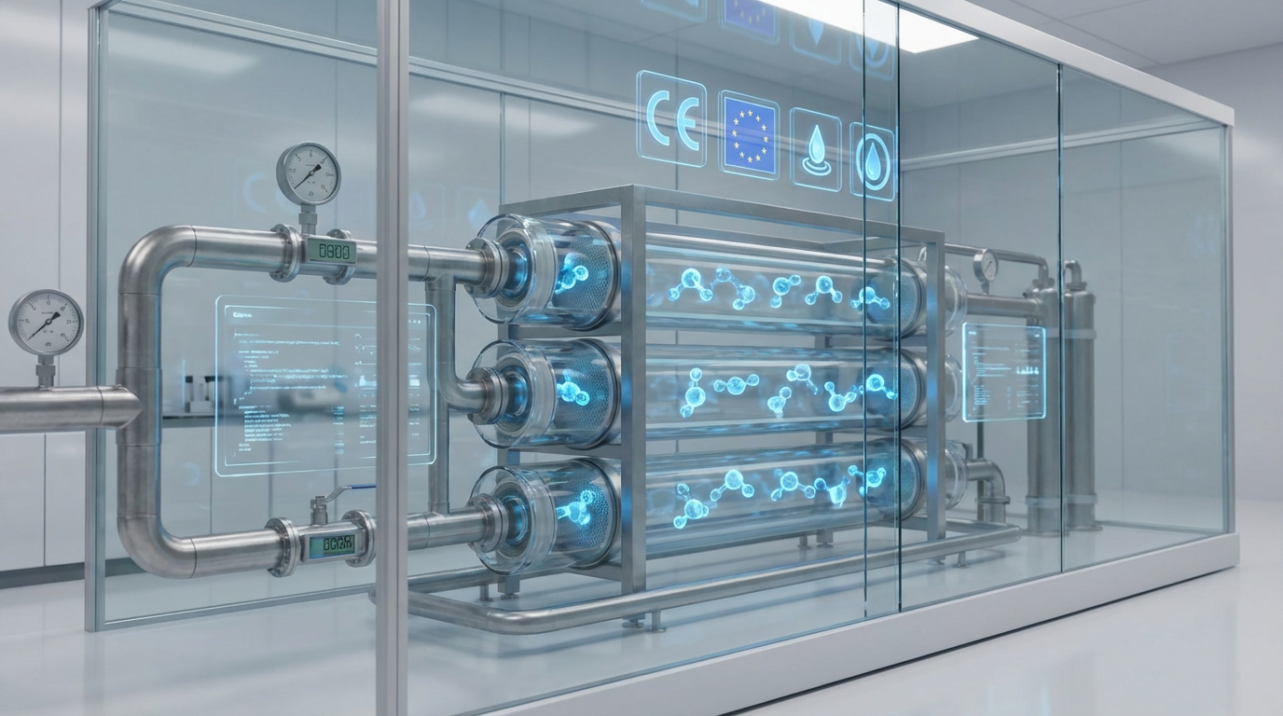

How European Rules Translate Into Practical Leak Protection

While there is no single “European RO leak protection directive,” various rules push designers and operators toward robust leak control. The table below summarizes how key regulatory themes, drawn from the research notes, map onto leak‑related design choices.

Regulatory theme |

Example framework from the notes |

Implications for RO leak protection |

Drinking‑water quality |

EU Drinking Water Directive; UK Drinking Water Inspectorate oversight; European Pharmacopoeia for pharmaceutical water |

Systems must remain closed and hygienic so that no leaks allow intrusion of contaminants or uncontrolled contact with non‑approved materials. Sudden pressure drops from leaks can also compromise barrier performance and monitoring. |

Food and beverage contact |

EU rules on materials in contact with food; UK Materials and Articles in Contact with Food Regulations |

Membranes, housings, seals, and fittings must not leach harmful substances or off‑flavors. Leaks that expose non‑food‑grade parts or create stagnant pockets are inconsistent with this requirement. |

Protection of public supply |

Water Supply (Water Fittings) Regulations in the UK |

Backflow prevention, air gaps, and proper waste connections are mandatory. Leaks or cross‑connections around RO units must not create a route for contaminated water to return to the mains. |

Environmental discharges |

Water Framework Directive; Marine Strategy Framework Directive; revised Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive |

Brine and wastewater must be discharged only through permitted outlets and under specified conditions. Leaks in concentrate lines or storage tanks undermine environmental impact assessments and can harm surface and coastal waters. |

Chemical and biocide safety |

REACH and UK REACH; Biocidal Products Regulation |

Chemical dosing circuits, cleaning lines, and storage tanks must be designed to prevent leaks that could expose workers or enter the environment. Spill containment and leak detection around chemical areas are important. |

Product, pressure, and electrical safety |

CE marking; RoHS; General Product Safety Regulation; Electricity at Work and Pressure Systems Safety Regulations |

High‑pressure piping and electrical equipment must be protected from water intrusion. Design choices like double‑walled hoses, drip trays, and leak sensors under skids or cabinets contribute directly to compliance. |

Waste and circular economy |

EU waste hierarchy; REMEMBRANE project; ScienceDirect study on RO membrane waste |

Systems should be built and operated so membranes reach their full life and can be removed, reused, or recycled. Leaks that accelerate corrosion or fouling shorten membrane life and increase waste, which conflicts with circular‑economy goals. |

This is how “soft” leak protection requirements emerge. Even if a regulation never mentions the word “leak,” it demands outcomes that are almost impossible to achieve if leaks are accepted as normal.

Leak‑Resilient Home RO Systems in a European Context

For home users, leak protection is about peace of mind as much as compliance. Many of the European families I advise live in apartments with neighbors above and below, metered water, and premium cabinetry. A slow leak in an under‑sink RO system can easily become an insurance claim.

Choosing the Right System Features

The University of Nevada, Reno Extension notes that higher‑end RO systems often include an automatic shutoff valve that stops feed water when the storage tank is full. This prevents unnecessary wastewater when no more permeate is needed. Low‑cost units may lack this feature and continue to send concentrate to the drain, even when the tank is full.

NU Aqua describes a separate leak stop valve that sits under the system with an absorbent “puck.” When water from a leak wets the puck, the valve automatically shuts off the feed. For this to work, the tubing must be fully inserted and locked, and the puck must sit correctly in its compartment before you close the lid.

From a European‑standards perspective, these are not legal requirements for a domestic under‑sink unit, but they align strongly with policy goals. Automatic shutoff improves water efficiency, which matters in water‑scarce regions highlighted by the European Commission’s Blue Economy work. A mechanical leak‑stop device dramatically reduces the chance that a small drip becomes a major damage event.

I generally steer European homeowners toward RO systems that combine both: a tank‑based automatic shutoff and a mechanical leak‑stop valve or electronic leak sensor with shutoff capability.

Installation Practices That Meet European Expectations

Most of the leaks I encounter in residential RO systems trace back to installation:

Feed‑water adapters must be threaded and sealed correctly. The NU Aqua guide recommends wrapping Teflon tape around the adapter threads before tightening to avoid small gaps that lead to seepage. Tabs on push‑fit fittings must be fully engaged, and tubing must be pushed in to the stop and then pulled back slightly to lock the internal seal.

Parker & Sons emphasize not over‑tightening fittings and o‑rings, which can distort seals and create leaks that only appear under full pressure. They also highlight the role of high municipal pressure in causing leaks. In some European cities, especially where apartment blocks climb ten or more floors, static pressures can be well above what a small RO system expects. In those situations, adding a pressure‑reducing valve upstream of the RO unit is a simple, standards‑aligned step.

In the UK and some other countries, connecting a treatment device directly to the mains may require notifying your water supplier and ensuring appropriate backflow protection is in place. Even when that is not explicitly required where you live, it is wise to design as if an inspector were going to review your work against those benchmarks.

Routine Maintenance to Stay Ahead of Leaks

Leak protection is not a one‑time installation task. It is an ongoing habit.

Realtruetek’s maintenance guidance suggests replacing pre‑filters every six to twelve months, post‑filters about every one to two years, and the RO membrane every two to three years depending on water quality and usage. Filters that are left in place too long clog and increase pressure across housings and seals, raising leak risk.

System sanitization at least once a year is also recommended. That means shutting off the water, draining the tank, removing filters and membrane, cleaning housings with a non‑toxic disinfectant, reassembling, and flushing thoroughly. This removes biofilm that can mask small leaks and helps maintain taste and odor quality.

NU Aqua and Parker & Sons both stress the value of regular visual inspection and listening for unusual sounds such as persistent hissing or gurgling. Those can indicate a small continuous flow to drain or a hidden leak. Parker & Sons further recommend annual professional servicing to catch issues that untrained eyes might miss.

In my own practice, I encourage clients to schedule filter changes and inspections on a calendar, not “when they remember.” Aligning those visits with other recurring tasks, such as boiler servicing, is a practical way to keep leak protection from becoming an afterthought.

Leak Protection for Commercial, Lab, and Desalination RO

Commercial, laboratory, and municipal RO systems in Europe operate under tighter scrutiny and often in more complex regulatory environments than household units. Leak protection here is part of a broader strategy that combines water and energy efficiency with environmental stewardship.

Water and Energy Efficiency as a Driver

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense at Work guidance points out that mechanical systems like cooling towers, boilers, and single‑pass cooling can dominate water use in commercial facilities. In laboratories and hospitals, steam sterilizers and reverse osmosis systems alone can account for several percent of total facility water use.

A detailed analysis in the journal Energies of an upgraded RO plant in North Cyprus shows how smarter design can cut both costs and external environmental impacts. By replacing pumps and membranes with more efficient models, the upgraded plant roughly halved its electricity use per unit of water, reduced purchases of treated wastewater, and lowered overall variable costs to about half those of the existing plant. Over a twenty‑year period, the net present value of these savings was substantial, with a payback time of less than two years.

Because North Cyprus relies heavily on heavy‑fuel oil steam turbines and large diesel generators, the study went further and monetized emission damages from pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, fine particulate matter, methane, and carbon dioxide. Cutting RO energy use translated directly into lower health and climate damage costs.

Leak protection plays into this because even small leaks in high‑flow plants can waste significant volumes and force equipment to work harder. Poorly controlled brine and permeate leaks make it difficult to achieve the high recoveries and energy efficiencies that modern design software targets. When a plant is upgraded for efficiency, it is the ideal moment to reinforce leak detection, drip containment, and structural integrity of piping.

Brine, Chemical, and Wastewater Containment

European environmental directives require that discharges occur under controlled conditions. The Blue Economy desalination overview, along with Mediterranean case studies, shows how desalination plants interact with agriculture and coastal ecosystems. Research cited there and in the membrane‑waste studies emphasizes managing brine impacts on seafloor communities and integrating desalination into basin‑wide planning.

Practically, that translates into design choices such as:

Placing brine pipelines in accessible, inspectable corridors or galleries rather than buried without monitoring. Providing bunds and secondary containment around chemical tanks, high‑salinity equalization tanks, and critical pumps. Installing leak detection sensors in sumps, trenches, and under raised skids, with alarms integrated into plant control systems. Ensuring that floor drains route to appropriate treatment rather than directly to storm sewers.

These measures are not just good engineering; they help operators document that their RO systems meet the expectations implicit in European water and marine‑protection law.

Asset Stewardship and Membrane Reuse

The REMEMBRANE LIFE project, conducted in Spain, provides a concrete example of how circular‑economy thinking can reshape RO practice. By installing a pilot membrane recovery plant, the project collected used membranes from several facilities, autopsied them, and optimized cleaning and recovery processes.

The results were striking. Around eighty percent of end‑of‑life membranes could be recovered for reuse as RO elements, while the remainder could be repurposed for less demanding applications such as brackish water treatment for irrigation. The average recovery cost in the pilot system was about $100.00 per membrane, with projections of about $45.00 in larger plants. New membranes for big desalination plants can cost in the range of $350.00 to $400.00, so the savings per membrane were substantial, even before counting reduced landfill disposal.

A complementary ScienceDirect study applied life‑cycle assessment to different end‑of‑life options for RO membranes, including reuse, conversion to lower‑pressure membranes, recycling of parts, energy recovery by incineration, and landfill. It concluded that reuse and conversion were generally the most environmentally favorable options, although transportation distances can influence climate impacts in some scenarios.

Leak protection sits upstream of all these efforts. A system plagued by leaks is likely also suffering from poor pretreatment, fouling, stress on housings, and irregular pressure profiles that shorten membrane life. By designing and maintaining systems so that leaks are minimized and quickly resolved, operators give membranes the best chance to reach the condition where reuse or conversion is viable, rather than failing catastrophically and heading straight to disposal.

Pros and Cons of Aggressive Leak Protection

It is worth acknowledging that leak protection is not free. More sensors, valves, containment structures, and inspections add cost and complexity, especially in small systems.

The benefits are significant, though. In homes, they include less risk of water damage, lower water bills in metered systems, and fewer disruptions to daily hydration routines. In commercial and municipal settings, they translate into easier compliance with European drinking‑water, environmental, and workplace‑safety rules, lower operating costs from reduced water and energy waste, and better alignment with circular‑economy policies.

There is also a psychological dimension. When people trust that their RO system is safe, well contained, and properly maintained, they are more willing to use it as their primary hydration source. That is a quiet but powerful contribution to public health.

Common Questions About RO, Europe, and Leak Protection

Is reverse osmosis water banned in Europe?

A detailed article on the “main problems with RO systems” makes this clear: there is no total ban on RO water in Europe. Instead, the European Union’s Drinking Water Directive and national regulations require that drinking water meet certain mineral and quality standards. Because RO removes both harmful contaminants and beneficial minerals such as calcium and magnesium, some public health experts in countries like Germany and France are cautious about using it as the sole treatment step for public supply. Those countries often prefer technologies that retain minerals or they remineralize RO water before distribution. For household systems and specialized industrial uses, RO remains widely used, provided the water meets applicable quality standards.

Are leak detectors and leak‑stop valves legally required on every RO system?

European regulations generally set performance and safety outcomes rather than prescribing exact device types. They do not, for example, mandate that every under‑sink RO system must have a specific brand of leak‑stop valve. However, in higher‑risk settings such as food production, healthcare, and laboratories, safety management systems like Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) require you to identify hazards, define critical control points, and implement controls and monitoring. For RO systems, that often includes measures to detect and shut off leaks, especially where a leak could contaminate product water or damage critical infrastructure. In residential settings, many manufacturers now include mechanical leak‑stop devices as standard, not because a regulation spells it out line by line, but because they align with modern expectations for water‑efficient, damage‑preventing design.

How often should I check my home RO system for leaks?

The maintenance guidance in the Realtruetek and NU Aqua materials points to a sensible rhythm. Pre‑filters should be replaced roughly every six to twelve months, post‑filters about every one to two years, and membranes every two to three years depending on use and local water quality. Each of those filter‑change events is an ideal time to check for moisture around housings, fittings, and the storage tank, and to listen for any unusual hissing or gurgling that might signal a problem. An annual full sanitization and inspection, including checking tubing connections and the leak stop valve, is a good baseline. If your home has particularly high water pressure or if you have had leaks before, more frequent checks are wise. For larger or more critical systems, such as in small clinics or food businesses, an annual professional inspection is typically justified by the risk reduction.

Protecting against leaks is not a luxury add‑on for RO systems in Europe; it is the practical expression of a broader commitment to safe hydration, resilient infrastructure, and healthy aquatic ecosystems. When you choose, install, and maintain your RO system with leak protection at the center, you are not just protecting a cabinet or a floor. You are aligning your daily drinking water habits with the best of European water stewardship.

References

- https://extension.unr.edu/publication.aspx?PubID=4785

- https://www.academia.edu/92346397/Reverse_osmosis_membrane_element_integrity_evaluation_using_imperfection_model

- https://www.epa.gov/watersense/best-management-practices

- http://pdclab.seas.ucla.edu/Publications/ABartman/Bartman2011_DES.pdf

- https://www.umaryland.edu/media/umb/af/dc/documents/division-22/221101P---Leak-Test-Plumbing-Piping-System-08-10-2024.pdf

- https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc778773/m2/1/high_res_d/827721.pdf

- https://www.aquasana.com/info/3-tips-for-maintaining-a-home-reverse-osmosis-system-pd.html?srsltid=AfmBOoppMY015zNBjY2D5aqHcM_EDLcUpjHI4VfbfXCur9qSU19EqWl3

- https://www.brotherfiltration.com/the-impact-of-reverse-osmosis-on-global-water-systems/

- https://www.chunkerowaterplant.com/news/main-problems-with-ro-systems

- https://blue-economy-observatory.ec.europa.eu/eu-blue-economy-sectors/desalination_en

Share:

Why 304 Stainless Steel Faucets Cost More Than Copper Faucets

Carbon Fiber Filters vs. Traditional Activated Carbon: Which Is Better For Your Home Water?