As more homes and buildings combine municipal water with wells, rainwater, condensate recovery, or other alternative sources, I see a recurring pattern: people focus on saving water and money, but underestimate the complexity of keeping those sources safely separated. From a water wellness perspective, dual water source systems are powerful tools for resilience and sustainability, yet they can also create hidden pathways for contamination if they are not designed and managed carefully.

This article walks through practical, science-backed methods to prevent cross-contamination when you use more than one water source. The goal is to give you the same lens that public health agencies, utilities, and water engineers use, translated into clear, actionable guidance for your home or facility.

What Dual Water Source Systems Are (And Why They Need Extra Care)

A dual water source system is any plumbing setup that draws from two distinct supplies. Typical examples include a home that uses city water for drinking and a private well for irrigation, a building that adds harvested rainwater or HVAC condensate for toilet flushing and cooling, or a facility that mixes desalinated or reverse-osmosis water with a municipal connection.

In all of these, one source is typically considered potable, intended for drinking and food preparation, and the other is non-potable, intended for uses such as irrigation, cooling towers, toilet flushing, or process water. The non-potable side can contain physical particles, chemicals, biological contaminants, or even radiological substances, as described by global water safety guidance summarized by NCBI and family-focused advice from Allianz Care.

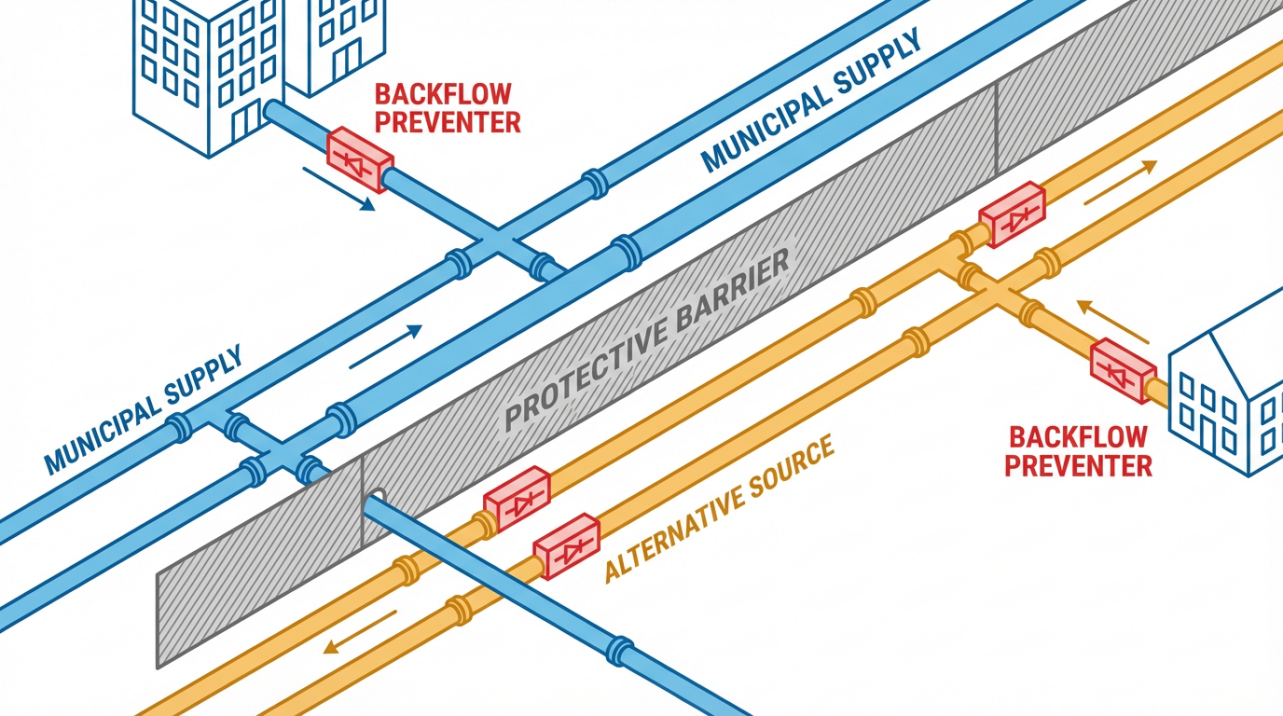

Cross-contamination becomes a critical issue because a dual system creates more places where potable and non-potable water come near each other. If any physical link or pressure event connects them, contaminants from the “secondary” side can be pulled or pushed into your drinking water line. Municipal treatment cannot protect you from what happens inside your premise plumbing, which is why water safety plans and management programs emphasize in-building control as a separate layer of protection.

Concern Worldwide notes that around a million people die each year from water contamination and that a very large fraction of wastewater globally is discharged untreated. Even in high-income regions, events like the Flint, Michigan crisis show that water safety cannot be taken for granted. Within buildings, cross-connections and backflow events have been identified by EPA and CDC reviews as a major cause of distribution system–related outbreaks in the United States, historically accounting for roughly half of documented contamination incidents.

A dual-source plumbing layout, if not properly protected, increases your exposure to exactly this kind of risk.

Cross-Connections and Backflow: How Contamination Actually Moves

To prevent cross-contamination, you first need a clear mental model of how clean and dirty water can mix in a dual-source setup. Most of the incidents I see reduce to two core concepts: cross-connections and backflow.

A cross-connection is any actual or potential link between your potable water system and a non-potable source. Sources can include irrigation lines with standing water, wells and ponds, fire sprinklers with additives, boilers, chemical injection systems, buckets, pools, spa tubs, wash-down hoses, or industrial processes. Multiple sources, including American Water, municipal utilities, and plumbing safety experts, use essentially this same definition. In a dual water source system, a cross-connection might be as obvious as a valve that ties your well line and municipal line together, or as subtle as a hose from your alternative water tank dipped into a sink fed by drinking water.

Backflow is the unwanted reversal of water flow that moves contaminants through a cross-connection into the potable system. American Water and several utility guides describe two main mechanisms. Backpressure occurs when pressure on the non-potable or downstream side becomes higher than the pressure in the potable line and pushes water backwards. This can happen if a pump on your well system, boiler, or process equipment overpowers the city supply pressure. Backsiphonage occurs when the pressure in the potable line drops, creating a partial vacuum that sucks water backward from connected fixtures or piping. Water main breaks, firefighting, hydrant flushing, and heavy peak demand can all create these negative pressure events.

The International Code Council further distinguishes between direct cross-connections, which can experience both backpressure and backsiphonage, and indirect cross-connections, which are only vulnerable to backsiphonage. In practice, that means a hard-piped connection between a reclaimed water line and your domestic cold-water line behaves very differently from a hose hanging above a trough. Both can be dangerous, but the first is much more likely to create a serious contamination incident when pressure conditions change.

Because dual-source systems by definition introduce more non-potable piping and equipment, they inherently create more opportunities for cross-connections. The key is to make sure every potential connection is either eliminated or permanently protected.

High-Risk Spots in Dual Water Source Systems

From inspection programs in Michigan, Massachusetts, and many municipal cross-connection control programs summarized in state and EPA guidance, several patterns emerge. The same categories of hazard show up again and again, and dual-source layouts make them even more important to address.

Outdoor irrigation and wells are consistent hot spots. The American Water Works Association considers any irrigation system tied to a public water main to be a high health hazard. When you add a second source such as a private well, pond, cistern, or fertilizing injector, risk increases further. Standing water around sprinkler heads, injectors that feed fertilizers or pesticides, and pumps that can develop significant pressure all set the stage for backflow if the potable side ever loses pressure.

Hose connections are another major cause. A town water department in Massachusetts reports that over half of documented cross-connection incidents involve garden hoses. Simply leaving a hose submerged in a bucket, hot tub, pet dish, or chemical sprayer during a pressure dip can draw contaminated liquid back into the house piping. In a dual-source system, hoses are often used to transfer water from one source to another, such as filling a tank from a well or rinsing equipment with alternative water. Every submerged hose in that context is a potential contamination pathway.

Mixed-source mechanical equipment creates a third high-risk category. Cooling towers, boilers, humidifiers, and other mechanical systems may use a blend of potable water and non-potable makeup, such as condensate or RO reject water. Cooling towers in particular have been repeatedly identified, in Legionella-focused water management guidance from ASHRAE-aligned sources and Tower Water, as common sources of bacterial spread in buildings. Where dual sources feed these systems, proper backflow protection and operational monitoring are essential to prevent contaminants from traveling back into the building’s potable lines.

Healthcare and senior living facilities represent a special case. CDC emphasizes that even though tap water generally meets regulatory standards, it is not sterile, and patients in these settings are more vulnerable to opportunistic pathogens of premise plumbing such as Legionella and certain nontuberculous mycobacteria. When a facility also uses alternative water sources for cooling, irrigation, or process needs, the complexity of the plumbing increases while patient tolerance for failure decreases, which is why CDC, CMS, and other bodies require formal water management programs aligned with ASHRAE standards.

Core Prevention Strategies for Dual Water Source Systems

The good news is that the same prevention principles used by utilities, hospitals, and large facilities can be right-sized for homes and smaller buildings. Whether I am looking at a modest house with a well and city connection, or a campus-scale condensate recovery project, I find that a small set of strategies does most of the safety work.

Design for Physical Separation and System Isolation

The safest dual water source systems are designed so that potable and non-potable water never directly touch each other in the first place. Hansen’s Plumbing, American Water, and multiple state programs stress the importance of physically separate piping for potable and non-potable networks, especially when a private well is used alongside municipal water.

In practice, that means running completely separate pipe networks when feasible, with no valves that can directly tie one source to the other. Where water must be transferred from a non-potable source into a potable fixture, the preferred method is an air gap, a vertical physical separation between the drinking water outlet and the highest possible water level in the receiving vessel. The International Plumbing Code and ICC commentary treat air gaps as the gold standard because they are not reliant on mechanical parts.

System isolation is equally important during maintenance or abnormal events. As noted in plumbing guidance summarized by Team Curious, isolating sections of the system during maintenance helps contain any contamination risk while work is performed. In a dual-source context, that can mean isolating the well or cistern side while servicing a pump, locking out crossover valves during testing, and clearly labeling which valves should never be opened simultaneously.

The ICC article also introduces the concepts of containment and isolation protection. Containment assemblies, often located just downstream of the water meter, protect the public system from anything in the building. Isolation devices are installed at points where hazards exist inside the building, such as an irrigation branch or boiler feed. In dual-source systems, you may need both: a containment backflow assembly for the entire building plus dedicated isolation devices on branches that connect to wells, rainwater, or other alternative sources.

Use the Right Backflow Prevention Devices

Where physical separation is not possible, or when codes require additional protection, mechanical backflow prevention devices become the frontline defense. Different devices are suited for different hazard levels and hydraulic conditions, as described by ICC, American Water, and multiple utility programs.

A high-level comparison is helpful when planning a dual-source system.

Device or method |

How it protects |

Typical role in dual-source systems |

Key limitations |

Air gap |

Maintains a physical distance between outlet and water surface so water cannot flow backward |

Safest option where potable water discharges into tanks, sumps, or basins fed by wells, rainwater, or condensate |

Requires space and proper installation height; can be bypassed by later piping changes |

Hose bib vacuum breaker or atmospheric vacuum breaker |

Admits air when pressure drops, breaking siphon action on hoses or small branches |

Protects hose connections and some irrigation branches where alternative water or chemicals are present |

Must not be under continuous pressure depending on type; can fail if not maintained |

Double-check valve assembly (DCVA) or dual-check valves |

Two check valves in series to stop reverse flow, used for moderate hazards |

Often used on irrigation lines, fire sprinklers, or dual-source equipment labeled as moderate risk |

Not adequate for high health hazards; must be tested where devices are testable |

Reduced-pressure principle assembly (RP or RPZ) |

Two check valves plus a relief valve that discharges if either check fails, keeping contamination from reaching potable side |

Used where high health hazards exist, such as irrigation with chemical injectors, certain industrial processes, or lines that can be supplied by wells or ponds |

More complex, requires regular testing and drain provisions; higher installation cost |

Pressure vacuum breaker or similar assemblies |

Protects against backsiphonage when outlets are elevated above supply |

Common on irrigation and some alternative water systems that can siphon back into potable lines |

Does not protect against backpressure; installation height and orientation matter |

For basic hose connections, low-cost hose bib vacuum breakers recommended by utilities like East Longmeadow are a simple, high-impact upgrade. They screw onto threaded outdoor faucets and dramatically reduce the risk that a submerged hose will back-siphon contaminated water.

For more complex dual-source arrangements such as irrigation systems fed by both city water and a private well, or equipment with chemical injection, American Water, ICC, and MyWater guidance all point toward higher levels of protection. That usually means an RP assembly or an air gap for high hazards, and a DCVA or pressure vacuum breaker only where the risk is truly moderate and local codes permit it.

Because the correct device depends on pressure conditions, hazard type, and local regulations, multiple state programs stress working with trained cross-connection inspectors or certified backflow testers when selecting and installing devices.

Build and Maintain a Water Management Plan

Dual-source systems are dynamic. Pumps and controls age, people change how spaces are used, and new equipment is added. That is why both building-focused articles and public health guidance under NCBI emphasize formal water management plans and water safety plans rather than one-time fixes.

A water management plan, as described in guides from Automech Group and Tower Water, is a structured, regularly updated approach to mapping how water moves through your building, identifying risk points, and defining control measures. For a dual-source system, the plan should clearly document every place potable and non-potable water are present, how they are separated or protected, and what monitoring or testing is required.

Key elements typically include a multidisciplinary team, even if in a small facility that simply means an owner, a maintenance lead, and a water treatment professional. The team maps the system using diagrams, identifies stagnant zones where disinfectants might not reach, flags high-risk applications such as cooling towers, humidifiers, and any equipment that generates mist, and sets measurable goals related to both safety and efficiency.

CDC and accreditation bodies such as The Joint Commission consider water management programs aligned with ASHRAE standards essential for hospitals and nursing homes, in part because they limit growth of opportunistic pathogens in premise plumbing. The same underlying logic applies to dual-source commercial buildings: defining control limits, documenting maintenance, and planning responses before something goes wrong gives you a far better chance of avoiding a contamination event or catching it early.

Monitor, Test, and Service Backflow Devices Regularly

Mechanical backflow preventers are not “set and forget” devices. State programs from Michigan and city programs such as Grand Rapids describe substantial failure rates when backflow assemblies are left untested. Springs fatigue, check valves foul, and relief valves stick.

Because of this, many jurisdictions require that testable backflow prevention assemblies be checked on a defined schedule, often annually, by professionals holding credentials such as ASSE 5110. The customer is usually responsible for arranging the test, paying for repairs, and submitting test reports, while the water utility maintains the authority to enforce compliance.

In a dual-source system, these testing requirements are even more important. Assemblies that separate potable lines from wells, rainwater cisterns, cooling towers, or chemical processes protect not just your building but often your neighbors as well. Michigan’s Safe Drinking Water Act rules require community water supplies to run cross-connection prevention programs that include inspection, testing, and recordkeeping for all customer types, not just large industrial users.

From a practical standpoint, it is wise to align your dual-source maintenance schedule with these regulatory expectations, even if your specific installation is not yet required to test annually. Combining periodic inspections, valve exercises, and device testing with good recordkeeping gives you both real safety benefits and documentation you can share with local authorities, insurers, or auditors if questions arise.

Control Everyday Behaviors that Create Cross-Connections

Many contamination events do not start with complex engineering failures but with everyday behaviors. Multiple sources, including Hansen’s Plumbing, American Water, and municipal guides, stress that homeowner and staff education is one of the most cost-effective controls.

Avoid submerging hoses or hose ends in any non-potable liquid, including buckets of cleaning chemicals, livestock troughs, pools, spa tubs, or even muddy lawn depressions. Never attach a hose to a chemical sprayer or pressure washer without built-in backflow protection. After using hose-end sprayers, avoid leaving them under pressure continuously.

Teach household members and staff to recognize warning signs of possible backflow or cross-connection issues. Hansen’s Plumbing notes that sudden changes in water color, unusual tastes or odors, unexplained pressure drops, gurgling noises, or several people in the household becoming ill at once can all indicate a problem. If you operate a dual-source system and notice these signs, isolating the alternative source, bypassing non-essential branches, and calling a qualified plumber or cross-connection specialist promptly is a prudent course of action.

Manage Alternative Water Sources Safely

The Federal Energy Management Program and the WaterSense at Work guidance highlight several alternative water sources that can significantly reduce potable water use in large facilities: captured HVAC condensate, atmospheric water generation, reverse osmosis reject water, foundation or sump water, cooling tower blowdown, and desalinated water. These are increasingly being used in smaller buildings as well, particularly for irrigation, cooling, and toilet flushing.

Each alternative source comes with its own water quality characteristics and cross-contamination risks. Condensate from cooling coils is initially very low in dissolved minerals, which makes it attractive for cooling tower makeup, but stored condensate can support bacterial growth and can pick up heavy metals from coil surfaces. FEMP therefore recommends disinfecting stored condensate and treating for heavy metals if needed. Reverse osmosis systems discharge a concentrate stream that may be high in dissolved solids, which can be appropriate for toilet flushing or some irrigation but must be kept away from potable piping and matched to tolerant plant species if used outdoors. Cooling tower blowdown has elevated mineral content and should be reused carefully to avoid scaling equipment or harming landscapes.

In all of these cases, the safest pattern in a dual-source design is to match alternative water to non-potable end uses only, keep its distribution network physically separated from potable lines, and protect any interfaces with appropriate backflow assemblies and air gaps. Facility guidelines emphasize the need to evaluate not just water quality but also energy use, cost, and environmental impacts before integrating each alternative source.

Scenario-Based Guidance for Common Dual Source Setups

Theory becomes much more tangible when you apply it to real layouts. Here are three situations that frequently come up in practice, with methods to prevent cross-contamination based on the combined guidance of plumbing safety experts, utilities, and public health organizations.

Home with City Water and a Private Well

Many households use city water for drinking and a private well for irrigation or outdoor spigots. Hansen’s Plumbing notes that where both potable and non-potable sources exist on the same property, systems should be physically separated and protected by appropriate backflow devices to remain code-compliant and prevent mixing.

For this scenario, a best-practice approach is to keep the well circuit hydraulically independent from the city water. That means no direct piping connection between the well discharge and any line receiving municipal water. If there is a need to fill a cistern or tank that can be supplied from both sources, an air gap is the preferred method at any point where city water discharges. Where codes permit and a direct connection is unavoidable, a high-hazard backflow assembly such as an RP device, installed and tested by certified professionals, may be required.

Outdoor hose bibbs fed by city water should have vacuum breakers or integrated backflow prevention, as recommended by both East Longmeadow and MyWater. This is especially important when hoses are used near irrigation trenches, fertilizer sprayers, or standing water that might be connected to the well system. Regular inspections and good habits, such as never leaving hoses submerged, further reduce risk.

Building Using Rainwater or Condensate alongside Municipal Supply

Commercial and institutional buildings increasingly capture roof runoff or HVAC condensate to feed irrigation, cooling towers, or even toilet flushing. FEMP and WaterSense at Work show that such alternative sources, when properly designed, can cut potable water use significantly.

To prevent cross-contamination, alternative water should be distributed on clearly labeled, separate piping. Where dual piping reaches fixtures, such as toilets or urinals that can be supplied by either potable water or treated graywater, internal plumbing must ensure that no direct cross-connection is present and that backflow prevention devices are installed according to the hazard level defined in plumbing codes.

Cooling towers that blend potable and alternative supply should be treated as high-risk applications within the water management plan. Tower Water emphasizes that cooling towers are among the most common sources of Legionella in buildings, making rigorous treatment, monitoring, and maintenance non-negotiable. Cross-connection control for tower makeup lines and blowdown reuse, combined with regular inspection and cleaning, helps prevent both microbial growth and contamination of potable distribution.

Healthcare or Senior Living Facility with Multiple Sources

Healthcare environments bring dual-source complexity and patient vulnerability together. CDC guidance explains that premise plumbing systems can harbor opportunistic pathogens that are relatively harmless to most people but dangerous to immunocompromised patients, and that water management programs aligned with ASHRAE standards are essential.

When a hospital or senior living facility also uses additional sources such as wells, cisterns, condensate, or process water, those sources must be rigorously controlled as part of the water management program. System diagrams should identify every source, its treatment train, its connections to the potable system, and all backflow prevention devices. Special attention should be given to sinks, showers, hoppers, and other fixtures where splashes from contaminated drains can reach patient care areas.

In these settings, backflow devices, air gaps, and careful sink design are not just technical niceties but infection control tools. CDC notes that sink and drain design, water age, dead ends, and pressure regulation all influence the growth and spread of opportunistic pathogens in premise plumbing. A dual-source healthcare system should therefore integrate cross-connection protection with broader infection prevention strategies, including cleaning, disinfecting, and operational controls.

Pros and Cons of Common Protection Methods

Different cross-contamination controls carry different tradeoffs. Understanding their strengths and limitations helps you choose the combination that fits your risk, budget, and regulatory context.

Strict physical separation, where potable and non-potable networks are completely independent, offers the highest inherent safety. There are no valves that can be accidentally opened and no devices that can fail. The tradeoff is flexibility: retrofitting strict separation into existing buildings can be expensive and sometimes impractical, particularly where fixtures were designed to be served by a single piping network.

Air gaps provide a robust barrier with low mechanical complexity. They are highly recommended wherever potable water discharges into non-potable tanks or basins and are widely accepted in plumbing codes. However, air gaps require the right vertical clearance, must be protected from later piping changes that can defeat their function, and can be aesthetically challenging in finished spaces.

Mechanical backflow preventers, from simple hose bib vacuum breakers to complex RP assemblies, make dual-source systems far more adaptable. They allow potable and non-potable networks to coexist and even cross paths as long as the device is correctly selected, installed, and maintained. The downside is that mechanical devices can and do fail. That is why state and municipal programs insist on periodic testing by certified professionals and why records of testing and maintenance are an important part of a defensible cross-connection control program.

Formal water management and safety plans add a layer of organizational discipline. They are essential in large or high-risk facilities and increasingly helpful even in smaller buildings with complex plumbing. Their main limitation is the need for time, expertise, and ongoing attention. A plan that sits in a drawer and is never updated offers little real-world protection.

Alternative water reuse schemes, when treated and managed correctly, deliver strong benefits on water conservation, cost, and resilience. Guidance from FEMP, WaterSense, and WBDG all show significant potable water savings from condensate capture, graywater reuse, and similar strategies. The flip side is that each new source adds complexity. Every additional pump, tank, or pipe is another potential cross-connection risk, so successful dual-source designs always pair reuse schemes with robust cross-connection control and operational monitoring.

FAQ: Everyday Questions about Dual Water Source Safety

If I already have a filter, do I still need backflow protection?

Point-of-use filters improve the quality of water once it reaches the tap, but they do not stop contaminated water from flowing backward into your home’s distribution or the public main. Backflow prevention devices work at the plumbing system level, upstream of any filters, and are designed to handle pressure reversals. Filters and backflow devices do different jobs and complement each other rather than substituting for one another.

How often should I review or update my water management plan?

Water management planning guidance from organizations such as CDC, ASHRAE-aligned groups, and international water safety plan frameworks recommend treating the plan as a living document. In practical terms, that means reviewing it at least annually and updating it whenever your plumbing, water sources, or building use change. Adding a new well, rainwater tank, cooling tower, or major fixture is a clear trigger for revisiting your dual-source risk assessment and control measures.

My irrigation system uses only city water. Do dual-source risks still apply?

Even if you currently use only municipal water, irrigation systems are still considered high-risk cross-connections by many utilities and by the American Water Works Association, especially if they include chemical injectors or are located in areas with standing water. The presence of an irrigation network means a second “environmental” source is effectively connected, because sprinkler heads and piping are exposed to soil, fertilizers, and runoff. If you later add a well or cistern, the system becomes a true dual-source layout and the case for robust backflow protection becomes even stronger.

Staying hydrated with confidence is about more than the filter at your faucet; it is about the integrity of every pipe and valve that leads there. When you design dual water source systems with separation, smart devices, disciplined management, and informed daily habits, you can enjoy the resilience and sustainability benefits of multiple water sources without sacrificing the safety of every glass you pour.

References

- https://www.eastlongmeadowma.gov/324/Preventing-Cross-Contamination

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/best-management-practice-14-alternative-water-sources

- https://www.epa.gov/watersense/best-management-practices

- https://www.oshkoshwi.gov/UtilityBilling/WaterSafety.pdf

- https://www.grandrapidsmi.gov/Government/Programs-and-Initiatives/Cross-Connection-Control

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK579462/

- https://www.cdc.gov/healthcare-associated-infections/php/toolkit/water-management.html

- https://www.twdb.texas.gov/publications/state_water_plan/2012/07.pdf

- https://www.michigan.gov/egle/about/organization/drinking-water-and-environmental-health/community-water-supply/cross-connection-control

- https://concernusa.org/news/water-crisis-solutions-that-work/

Share:

Understanding the Need for Soft Start Circuits in Large RO Systems

Understanding the Requirement for Freeze Protection in RO Systems in Europe