As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time at the intersection of water science and everyday kitchen reality. Many people know reverse osmosis as the “gold standard” of filtration, but then they taste the water, realize it can feel flat or overly stripped, and start asking about systems that clean their water without throwing away every trace of healthy minerals.

That is exactly where nanofiltration comes in.

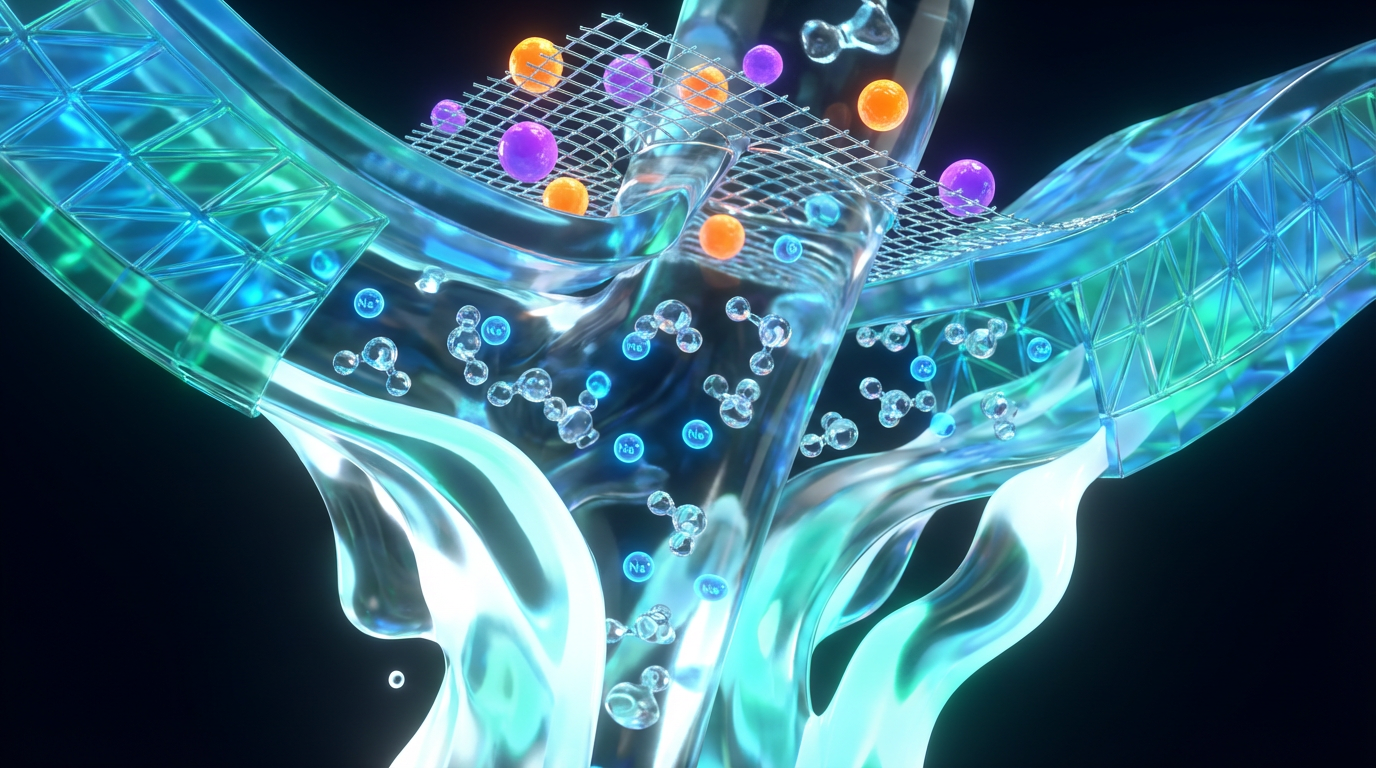

Nanofiltration (NF) membranes were designed to be selective, not ruthless. They remove a wide range of unwanted contaminants, soften the water, and still let a meaningful share of beneficial minerals through. Understanding how that is possible requires a quick dive into what happens at the nanoscale inside these membranes and how design choices shape what ends up in your glass.

In this article, I will walk through the core principles behind nanofiltration, explain how and why NF membranes retain minerals, compare NF with reverse osmosis and other common treatments, and translate all of that into practical guidance for choosing and operating a system at home or in a small office. The explanations are grounded in published research on nanofiltration and in real-world experience with installed systems.

What Nanofiltration Is And Where It Fits

Nanofiltration is a pressure-driven membrane technology that sits between ultrafiltration and reverse osmosis in terms of how tightly it filters. In simple terms, ultrafiltration mainly stops large particles and many microorganisms, reverse osmosis stops almost everything except water molecules, and nanofiltration sits in the middle, targeting a specific band of dissolved substances.

Research reviews on nanofiltration membranes describe NF as having a typical molecular weight cut-off around 200 to 1,000 daltons. That means it is very good at rejecting larger organic molecules and multivalent ions such as calcium, magnesium, and sulfate, while many smaller monovalent ions like sodium and chloride can pass to a significant degree. Pore sizes are often described as being around a few nanometers across, which is why the term “nanofiltration” is used.

For drinking water and home hydration, that positioning is powerful. A review on nanofiltration for drinking water treatment published on PubMed Central notes that typical NF systems can remove more than 90 percent of hardness-forming divalent ions and often more than 70 to 90 percent of natural organic matter and many pesticides and pharmaceuticals, all while allowing much of the monovalent salts to remain. That means softer, safer water with less scale and color, without the near-zero mineral content characteristic of classic reverse osmosis.

Nanofiltration is also used by municipalities and industries. Studies cited in environmental and chemical engineering journals describe NF applied to remove pesticides and natural organic matter from surface water, soften groundwater, treat textile and dairy wastewater, and polish treated sewage before reuse. In PFAS-focused work summarized by Crystal Quest, nanofiltration systems configured for “forever chemical” removal have reached roughly 90 to 99 percent PFAS reduction while consuming about 30 to 50 percent less energy than reverse osmosis for similar performance.

For home users, though, the most relevant feature of nanofiltration is this: it is a “smart softening” membrane that can remove problem contaminants and hardness, while retaining a meaningful fraction of beneficial minerals that support taste and hydration.

How Nanofiltration Membranes Separate Minerals

To understand mineral retention, it helps to picture what a nanofiltration membrane actually looks like and how it works when water flows across it.

The layered structure: more than just tiny holes

Modern nanofiltration membranes are usually thin-film composite structures. DuPont’s FilmTec nanofiltration products, for example, are described as having three layers: a strong polyester support web, a microporous polysulfone layer, and an ultra-thin polyamide barrier layer on top. The polyester gives mechanical strength, the polysulfone provides a porous scaffold, and the polyamide top layer is where the real separation happens.

Water is pumped along the surface under pressure, and a fraction of it permeates through that ultrathin barrier into the permeate channel, leaving many solutes behind in the concentrate stream. The membrane is not simply a sieve with cleanly drilled holes like a showerhead screen.

Instead, separation occurs through a combination of extremely small free volume in the polymer network and charge interactions at the membrane surface.

Size-based sieving at the nanoscale

One key mechanism is size exclusion. Many nanofiltration membranes are designed so that larger molecules above a certain molecular weight move slowly or not at all through the dense polyamide layer. Reviews in Springer’s nanofiltration literature describe typical NF molecular weight cut-offs of 200 to 1,000 daltons, which align with efficient rejection of many natural organic molecules, dyes, and larger dissolved contaminants.

This size-based effect is particularly important for keeping natural organic matter, many pesticides, and larger organic pollutants out of the drinking water. Those compounds tend to have molecular weights in the range that NF is optimized to reject.

However, mineral ions like calcium and sodium are not large molecules in the same sense. They are individual ions, each surrounded by water molecules, and they are small enough that size alone does not fully explain how the membrane treats them. That is where charge effects come into play.

Charge effects and Donnan exclusion

Most nanofiltration membranes used in drinking water applications carry a negative surface charge at typical tap water pH. Reviews on nanofiltration membranes explain that separation performance arises from two coupled mechanisms: steric (size) effects and electrostatic interactions often described as Donnan exclusion.

In practical terms, a negatively charged membrane will repel negatively charged ions (anions) such as sulfate or nitrate more strongly than it repels neutral molecules. It will also influence positively charged ions (cations) like calcium and magnesium, because those cations are paired with anions to maintain charge balance. The result is that multivalent ions feel a much stronger electrostatic “push back” at the membrane surface than monovalent ions do.

One review article notes that nanofiltration typically achieves more than 90 percent rejection of divalent ions such as calcium, magnesium, and sulfate under common drinking water conditions, while monovalent ions like sodium and chloride show more moderate rejections, often in a range of roughly 20 to 70 percent depending on membrane type and operating conditions. That selective rejection is the core of mineral retention: the system softens water by removing most hardness, but allows enough monovalent ions to pass so that the water does not become fully demineralized.

Why multivalent ions go and monovalent ions mostly stay

Putting size and charge together gives a clear picture of why nanofiltration behaves the way it does.

Multivalent ions such as calcium (two positive charges), magnesium (two positive charges), and sulfate (two negative charges) have stronger electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged membrane surface. They tend to have more tightly bound hydration shells as well. The combination of their charge, their interaction with counter-ions, and the membrane’s nanoscale structure makes it energetically unfavorable for them to cross, so they are largely rejected.

Monovalent ions like sodium and chloride feel a weaker electrostatic interaction and can more easily find pathways through the membrane’s free volume. As a result, they are only partially rejected. Studies comparing different nanofiltration membranes report that some “tighter” NF types behave almost like reverse osmosis for monovalent ions, while “looser” NF types let most monovalent salts pass and focus on removing hardness and organics.

That tunability is essential. It allows manufacturers to design NF elements that, for example, strongly soften water and remove organics but maintain more of the original mineral balance than a typical reverse osmosis membrane.

Mineral Retention: What Actually Stays In Your Water

If you look past the technical jargon, the key question for hydration is simple: after nanofiltration, which minerals are still in my water, and which are mostly gone?

Hardness minerals: calcium and magnesium

Hardness in water is driven primarily by calcium and magnesium ions. These are multivalent cations, and multiple reviews on nanofiltration agree that NF membranes reject them very efficiently. For drinking water applications, reported hardness removal is generally above 90 percent for typical NF elements when operated correctly, though actual performance varies with membrane design and feed water chemistry.

In everyday terms, that means nanofiltration acts as a highly effective softening barrier. Kettles and coffee machines accumulate much less scale, shower glass stays clearer, and soap lathers more easily. At the same time, some residual hardness often remains, especially if the water starts extremely hard or the membrane is relatively loose, so the water does not usually feel quite as “slippery” as water treated by sodium-based softeners.

From a hydration perspective, calcium and magnesium are valuable nutrients, but the majority of your intake typically comes from food, not water. The scientific literature on nanofiltration does not claim that NF water eliminates all calcium and magnesium, only that it substantially reduces them. In practice, I have seen NF-treated water from moderate-hardness municipal supplies still test with measurable, though lower, calcium and magnesium levels, especially when the system operates at modest recovery and the membrane is selected for mineral retention.

Light electrolytes: sodium, potassium, chloride, and bicarbonate

Monovalent ions such as sodium, potassium, and chloride behave quite differently. A practical overview from a water treatment provider notes that reverse osmosis membranes typically remove about 98 to 99 percent of monovalent ions, whereas nanofiltration often removes in the range of about 50 to 90 percent, depending on the specific membrane design.

That is a wide range, and in real projects I see it reflected in how different NF elements are marketed. Some are positioned as “low-salt softening membranes” with noticeable total dissolved solids reduction, while others are marketed mainly for hardness and organic removal, explicitly highlighting mineral retention.

Because sodium and chloride are partly retained, nanofiltration-treated water usually has a higher total dissolved solids reading than reverse osmosis water produced from the same source. That is one reason NF water tends to taste more like natural spring water or a good municipal supply, while RO water can taste “empty” until you remineralize it.

Bicarbonate, which contributes to alkalinity and buffering capacity, is also a monovalent species and may be partially retained. The exact behavior depends on the specific membrane chemistry and the anion pairing in the water, but the general pattern is that nanofiltration does not drive alkalinity down as aggressively as reverse osmosis does. This often leads to water that is less corrosive to plumbing and fixtures than very low alkalinity RO permeate.

Trace minerals and special cases

Trace minerals such as potassium, small amounts of iron or manganese, and other minor constituents can behave in more complex ways, especially when they form complexes or participate in larger structures with organic matter. Scientific articles examining specific ion removal show that nanofiltration performance for species such as nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium can be very variable, with reported removals ranging from low to high depending on membrane type, operating conditions, and water matrix.

The takeaway here is important for anyone choosing a system for health reasons. Nanofiltration is excellent at removing many organics, hardness, and a large fraction of heavy metals and PFAS, and it often retains enough monovalent ions to keep water from being completely demineralized. It is not, however, a universal guarantee for difficult inorganic contaminants such as nitrate and ammonium. If those are concerns in your water, you should confirm performance for the specific membrane you are considering and ensure the complete treatment train has been tested or certified for those targets.

Comparing Nanofiltration To Reverse Osmosis And Other Filters

Understanding mineral retention becomes easier when nanofiltration is seen alongside other common treatment technologies.

Technology |

Main focus of removal |

Mineral retention in drinking water use |

Typical pressure and energy behavior |

Typical water recovery |

Typical best use case |

Nanofiltration (NF) |

Hardness, many organics, many PFAS, some salts |

Retains a significant portion of monovalent ions |

Operates around roughly 100 to 300 psi with about 30–50% less energy than reverse osmosis in similar tasks |

Often about 80–95% |

Softening and contaminant removal when you want clean, good-tasting water with some minerals left |

Reverse osmosis (RO) |

Broad desalination of most dissolved salts and organics |

Very low mineral retention |

Often around 150 to 600 psi with higher energy use |

Often about 50–75% |

High-purity or high-salinity treatment, or when you must remove most dissolved solids |

Activated carbon filter |

Chlorine, many organics, taste and odor |

Does not selectively remove minerals |

No high pressure needed |

Near 100% |

Taste, odor, and basic chemical polishing, not full safety barrier |

Ion exchange softener |

Hardness (calcium, magnesium) swapped for sodium or potassium |

Minerals still present, but hardness converted |

Low pressure; relies on salt regeneration cycles |

Near 100% |

Whole-house softening where sodium addition is acceptable and full contaminant barrier is not the goal |

The PFAS-focused comparison provided by Crystal Quest highlights that nanofiltration can remove many PFAS compounds at roughly 90 to 99 percent, similar to reverse osmosis, while allowing better mineral retention, higher water recovery, and lower energy use. Activated carbon and ion exchange can also remove PFAS in many cases, but they do not provide the same broad rejection of hardness and a wide suite of organic pollutants that nanofiltration offers.

In my own project work, I often see nanofiltration chosen over reverse osmosis when three things are simultaneously true: users want a perceptible softness improvement, there is concern about modern contaminants such as PFAS or pesticides, and they prefer water that still tastes like natural mineral water rather than laboratory-grade pure water.

RO still has its place, particularly for very high salinity or when specific contaminants require nearly complete removal, but for many municipal and well waters, nanofiltration provides a better balance.

Health And Taste Implications Of Mineral-Retaining Filtration

From a hydration and wellness standpoint, mineral retention is about more than numbers on a lab report. It shapes both the physiological and sensory experience of drinking water throughout the day.

Minerals such as calcium and magnesium contribute to the total hardness and mouthfeel of water. While extreme hardness can create scale and off-flavors, moderate mineral levels are associated with a pleasant taste profile that many people prefer. Studies in nanofiltration reviews emphasize that NF-treated water is less aggressively demineralized than RO water, which can reduce corrosion risks and help maintain a more natural, less flat taste.

For most healthy adults, the primary sources of calcium and magnesium are food and, in some cases, supplements. Water contributes a variable share, depending on the local supply. When a nanofiltration system lowers hardness significantly, it can reduce that contribution, but it usually does not drive mineral levels as low as a strong RO system does. In taste tests I have run with families comparing NF and RO on the same feed water, people frequently describe NF water as “smoother” than their original tap or well water, yet less stark or empty than un-remineralized RO permeate.

Minerals also influence pH and buffering. Reverse osmosis permeate is often low in alkalinity and can be slightly more corrosive, which is why many RO systems include a remineralization or pH-conditioning cartridge. Because nanofiltration typically allows a portion of bicarbonate and other monovalent ions to pass, the resulting water usually maintains more buffering capacity. That can be beneficial for both plumbing longevity and taste, though the exact benefit depends heavily on the starting water chemistry.

From a safety perspective, nanofiltration’s strength lies in its multibarrier behavior when combined with appropriate pre-treatment. Reviews of nanofiltration for drinking water note high removal rates for many pesticides, pharmaceuticals, natural organic matter, and disinfection by-product precursors. Ceramic nanofiltration-type membranes have even achieved complete virus removal in controlled tests, with log reduction values exceeding World Health Organization recommendations.

As always, any specific health need should be discussed with a medical professional, especially for individuals with kidney disease or strict sodium limits. In those scenarios, it becomes particularly important to review the mineral rejection specifications of the chosen membrane and the overall treatment train.

Pros And Cons Of Nanofiltration For Drinking Water

Nanofiltration is not a magic wand, but it brings a strong set of advantages when the goal is healthier, better-tasting water with a respectful approach to mineral content.

On the positive side, NF provides high rejection of multivalent ions and many organic contaminants at lower pressures and energy use than reverse osmosis. It supports higher water recovery, often in the range of about 80 to 95 percent, which means less wastewater compared with many RO systems that may recover only about 50 to 75 percent of feed water. Because NF retains many monovalent ions, the resulting water tends to taste more natural, and its higher residual mineral content can reduce corrosion and the need for aggressive remineralization.

On the limitations side, nanofiltration is not intended for full seawater desalination or extremely high salinity brines, because its monovalent salt rejection is only partial. It can show variable performance on certain problem ions such as nitrate and ammonium, so those applications require careful membrane selection and validation. Like other membrane processes, NF is susceptible to fouling from organic matter, colloids, biofilm, and scaling, and it generates a concentrate stream that contains the removed contaminants and must be disposed of appropriately.

Economic assessments in the scientific literature suggest that when full demineralization is unnecessary, NF can be more energy-efficient and cost-effective than RO.

However, the overall cost and sustainability picture depends heavily on pretreatment, cleaning strategies, and concentrate management. For individual homes, the deciding factors are usually water quality, taste preference, maintenance comfort, and local plumbing constraints rather than large-scale life-cycle metrics.

Design Choices That Control Mineral Retention

Not all nanofiltration membranes behave the same way. Several design variables play a direct role in how much mineral ends up in your glass.

Membrane tightness and material

The “tightness” of a nanofiltration membrane is often expressed through its molecular weight cut-off and salt rejection curves. Review articles categorize NF membranes as “loose” or “tight” based on how they treat monovalent salts. Tighter NF membranes may have monovalent salt rejections that approach those of RO, which means they will remove more sodium and chloride and deliver lower total dissolved solids. Looser NF membranes, sometimes marketed primarily as softening membranes, focus on removing hardness and many organics while preserving most monovalent ions.

Most commercial NF elements for drinking water are polymeric thin-film composites with polyamide separation layers. Some newer research explores ceramic and mixed-matrix nanofiltration membranes, which can offer higher chemical and thermal stability and, in some cases, very high virus and bacterial removal. For residential and small office use, polymeric thin-film composites remain the most common due to their cost and availability.

Surface charge and chemistry

Membrane charge is just as important as tightness. Reviews in environmental journals explain that semi-aromatic polyamide nanofiltration membranes tend to rely strongly on electrostatic (Donnan) exclusion, meaning that their surface charge is a major driver of ion selectivity. Fully aromatic polyamide membranes may lean more on size exclusion.

For mineral retention, a negatively charged membrane at drinking-water pH helps repel multivalent anions such as sulfate and also influences how associated cations like calcium and magnesium partition across the membrane. In contrast, certain positively charged nanofiltration membranes are intentionally designed for applications such as dye removal, where attracting negatively charged dye molecules to the surface aids rejection. Those types are not typically chosen when the goal is pleasant, mineral-balanced drinking water.

Operating pressure, recovery, and crossflow

Operating conditions also affect mineral rejection. Pressure provides the driving force, and foundational membrane-technology primers note that water flux can be approximated as proportional to the difference between applied pressure and osmotic pressure. At higher net driving pressure, salts tend to be rejected more strongly up to a point, but pushing too hard can exacerbate fouling and scaling.

Recovery, defined as the ratio of permeate flow to feed flow, has an indirect effect. As recovery increases, solutes become more concentrated in the remaining feed channel, raising local osmotic pressure and scale risk. The DuPont reverse osmosis and nanofiltration design guidance emphasizes that there are practical limits to recovery that depend on feed water chemistry; exceeding those limits can reduce flux, complicate cleaning, and shift rejection behavior. For homeowners, that translates into trusting a well-designed system rather than manually trying to maximize recovery by restricting concentrate flow.

Crossflow velocity along the membrane surface helps sweep away accumulated solids and reduces concentration polarization. Lower crossflow can make fouling and scaling worse, which in turn can change the effective pore structure and surface charge, and ultimately alter mineral retention until the membrane is cleaned.

Pretreatment and fouling control

Fouling is one of the main realities of membrane operation. Reviews on nanofiltration repeatedly identify organic fouling, colloidal fouling, biofouling, and scaling as key limitations. To protect nanofiltration membranes and keep their mineral-selective behavior stable, pretreatment is essential.

In practice, that usually means a sediment filter capable of removing fine particles and a carbon filter to remove chlorine and many oxidants that can damage polyamide layers. Some systems add antiscalant dosing or upstream softening in very hard-water regions. PFAS-focused and municipal-scale studies also emphasize the value of pretreatment steps such as ultrafiltration or coagulation to remove organic matter and reduce fouling.

When fouling does occur, cleaning procedures restore performance. DuPont’s FilmTec nanofiltration products, for example, are designed to tolerate operation over a wide pH range and can be cleaned at both acidic and alkaline pH within specified conditions, allowing targeted removal of inorganic scale and organic deposits. For home systems, that cleaning is typically simplified to periodic filter changes and, when necessary, membrane replacement according to the manufacturer’s performance guidelines.

Practical Guidance For Homes And Small Offices

The science is helpful, but the final decision about nanofiltration happens in everyday kitchens and break rooms. Here is how I recommend thinking through NF adoption in a practical way.

When nanofiltration is a good fit

Nanofiltration usually shines when the source water has moderate to high hardness, measurable taste or color issues, or concerns about modern contaminants such as pesticides, pharmaceuticals, or PFAS, yet total dissolved solids are not extreme. If you want water that is clearly cleaner and softer than your tap water, but you dislike the taste of fully demineralized RO water, nanofiltration is often a strong candidate.

It is also attractive in situations where water conservation matters. PFAS treatment studies and municipal NF deployments report typical recoveries in the 80 to 95 percent range, substantially higher than many residential RO systems that may recover about half to three quarters of the feedwater. That can add up over years of daily use.

Nanofiltration is less appropriate as a standalone solution when you are dealing with seawater, very high salinity brackish water, or nitrate-dominated contamination that must be reduced reliably to very low levels. In those contexts, reverse osmosis, ion exchange, or specialized treatment steps often remain necessary, possibly alongside nanofiltration.

How to read mineral retention from product specs

You do not need a PhD to read a nanofiltration specification sheet, but a few terms matter. Manufacturers typically list percent rejection for key ions such as calcium, magnesium, sodium, chloride, and sulfate. They may also provide hardness, total dissolved solids, and specific contaminant rejection data.

For mineral-retaining drinking water, look for membranes that show high rejection for calcium and magnesium and for troublesome multivalent anions like sulfate, along with more moderate rejection for sodium and chloride. Some providers and reviews refer to these as “softening” nanofiltration membranes. If a spec sheet claims that the membrane removes more than 95 percent of sodium and chloride under typical conditions, it is functioning more like a reverse osmosis element and will produce lower-mineral water.

Also pay attention to whether the complete system blends or conditions the permeate. Some advanced NF-based systems mix a controlled portion of filtered but slightly less treated water back into the nanofiltration permeate to fine-tune mineral levels, or they use post-treatment cartridges to adjust pH and alkalinity. That type of thoughtful design can give very consistent taste and mineral content over varying feedwater.

Everyday operation and maintenance for stable performance

From a user’s standpoint, maintaining mineral retention is mostly about keeping the membrane healthy. That starts with pretreatment. Sediment cartridges should be replaced before they clog, rather than after the flow rate crashes. Carbon filters should be changed on schedule to protect the membrane from oxidants. If the system includes a softening or antiscalant step ahead of nanofiltration, that step should be maintained as specified as well.

Signs that an NF system needs attention include a noticeable drop in flow, a change in taste, or visible scale buildup in fixtures that had previously been clear. Industry maintenance guidance suggests that for large systems, operators track normalized permeate flux and start cleaning or replacing membranes when performance drifts by around 10 to 15 percent. At home scale, you are unlikely to calculate those values, but you can watch for clear symptoms and follow the manufacturer’s replacement intervals.

Because nanofiltration operates at lower typical pressures than reverse osmosis and often runs at higher recovery, noise and wastewater volume can also be less intrusive, which makes users more likely to keep using and maintaining the system correctly. In my experience, when maintenance feels manageable and the water tastes good, people stick with the system and reap the long-term health and appliance benefits.

Short FAQ On Nanofiltration And Minerals

Does nanofiltration remove all minerals from water?

No. Nanofiltration was specifically developed to be more selective than reverse osmosis. Research reviews and product data consistently show that NF membranes strongly reject multivalent ions such as calcium, magnesium, and sulfate, but allow a significant portion of monovalent ions such as sodium and chloride to pass. The exact balance depends on the membrane and operating conditions, but NF-treated water generally retains more minerals and has a more natural taste than fully demineralized RO permeate.

Is nanofiltration enough to handle PFAS and other modern contaminants?

For many PFAS compounds, yes, when the system is designed for that job. Data summarized by Crystal Quest indicate that nanofiltration systems configured with appropriate pretreatment can reach around 90 to 99 percent PFAS removal, with hybrid NF systems combining membrane filtration and adsorption achieving similar performance while reducing fouling. NF also performs well for many pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and natural organic matter. That said, you should always verify that a specific residential system has been tested or certified for the contaminants you care about.

If I already have reverse osmosis, should I switch to nanofiltration?

If your current RO system is meeting your safety needs but you are dissatisfied with the taste or would like higher water recovery and more mineral retention, it can be worth exploring nanofiltration. Some households choose to keep RO for a dedicated faucet where ultra-low-mineral water is needed and use NF or blended NF water for general drinking and cooking. The right choice depends on your source water, existing plumbing, and taste preferences.

Do I still need a remineralization cartridge with nanofiltration?

Often you do not strictly need one, especially if your source water starts with moderate mineral content and you choose an NF membrane that is designed for softening with partial mineral retention. However, some users still like post-treatment conditioning to adjust pH or to tune taste and mouthfeel. In that case, a well-designed remineralization stage can provide fine control without having to run the core membrane system harder than necessary.

Nanofiltration is one of the most useful tools we have today for creating water that is both cleaner and more naturally balanced. When you understand how these membranes selectively remove hardness and contaminants while allowing many beneficial minerals to remain, you can choose and operate a system with confidence. As a water wellness advocate, my goal is always the same: help you build a hydration environment at home where every glass is both safe and satisfying to drink.

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8617557/

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/chemical-engineering/articles/10.3389/fceng.2025.1695014/full

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367883342_Principles_of_nanofiltration_membrane_processes

- https://www.molewater.com/what-is-nanofiltration-in-water-treatment

- https://alliniwaterfilters.com/what-is-nanofiltration-and-how-can-it-improve-your-water-quality/?srsltid=AfmBOooI7xJgsMTkUJLwcG0MGOeWSOMzzOeDLWv5SANnmgPBWhIEAlIy

- https://hydramem.com/how-nanofiltration-enhances-water-quality/

- https://us.ionexchangeglobal.com/nanofiltration-in-water-treatment/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s44221-025-00492-x

- https://www.yasa.ltd/post/what-is-nanofiltration-nf-process-in-water-treatment

- https://rivamed.co.uk/industrial-treatment/membrane-technologies/nanofiltration-nf

Share:

How Capacitive Touch Control in Smart Faucets Achieves Water Resistance

Understanding the Effectiveness of 253.7 nm Wavelength UV Lamps