When I sit down with a family or a wellness-focused workplace to design a drinking water system, one of the first questions I hear is, “Will alkaline water make my blood less acidic?” The promise sounds simple and powerful: drink high‑pH water, “alkalize” your body, and unlock better health.

The science is more nuanced.

Research does show that certain mineral‑rich alkaline waters can shift some acid–base markers in the body. At the same time, independent medical centers consistently emphasize that your lungs and kidneys keep blood pH in a very tight range, and that neither diet nor water can swing it dramatically in healthy people. Understanding both sides is the key to making smart hydration choices, not just trendy ones.

In this article, I will unpack what we actually know from controlled studies, what “alkalinizing” really means, and how alkaline water fits into a practical home or office hydration strategy when your goal is supporting long‑term health rather than chasing hype.

pH Basics: From Tap Water To Blood

What pH Actually Measures

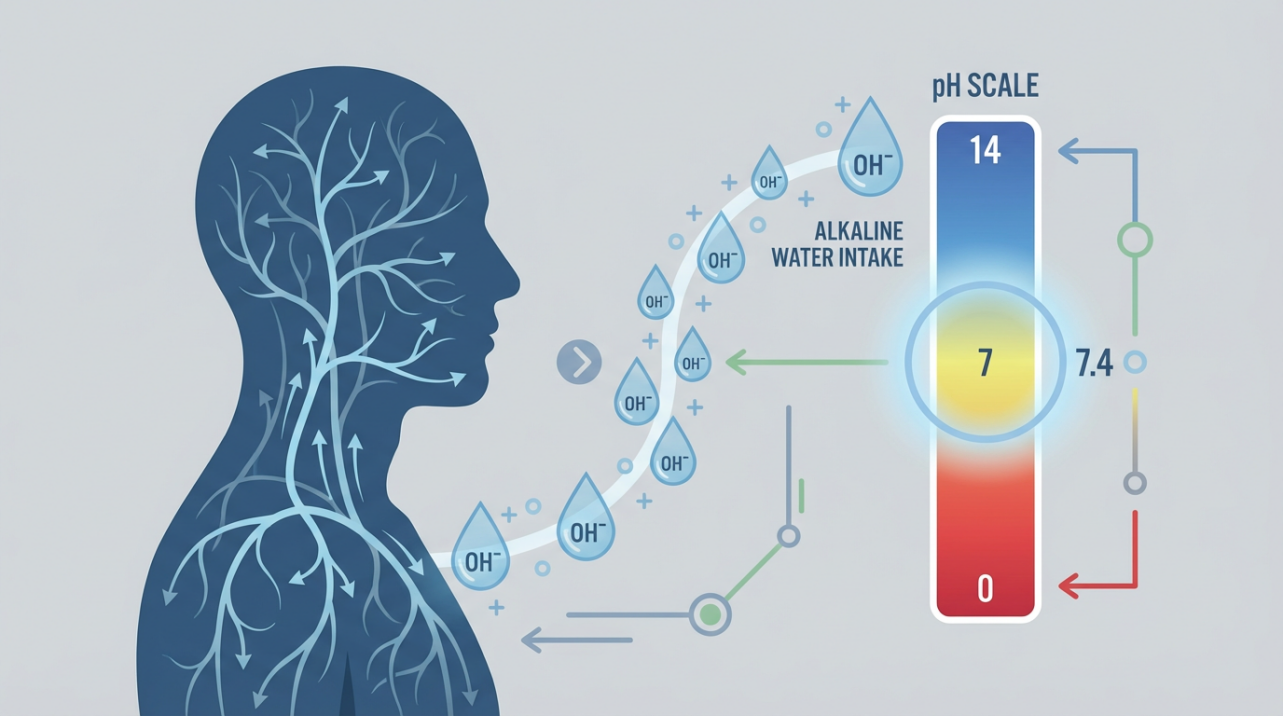

pH is a measure of how acidic or alkaline a solution is on a scale from 0 to 14. Values below 7 are acidic, 7 is neutral, and values above 7 are alkaline (or basic). Several of the medical and nutrition sources in the research notes, including Harvard Health and the American Institute for Cancer Research, point out a few anchor points on that scale.

Municipal tap water is usually regulated to a pH between about 6.5 and 8.5, with many systems landing near 7.0 to 7.5. Bottled “regular” waters tend to cluster around neutral pH 7. Bottled alkaline waters typically sit in the pH 8 to 9 range, while some specialty products and research waters are closer to pH 10.

Inside the body, pH is not uniform. A Cooper Institute educational article describes stomach fluid as very acidic, around pH 1.7, resting muscle around pH 7.2, bile and pancreatic juices around pH 8, and blood at about pH 7.4. This variation is normal and essential for digestion and metabolism.

To orient all of this, here is a simplified snapshot of pH in different places based on the research notes.

Location or fluid |

Typical pH range (approximate) |

What the sources emphasize |

Municipal tap water |

6.5–8.5 |

Regulated range for taste and corrosion control |

Regular bottled water |

Around 7.0 |

Essentially neutral |

Common alkaline bottled water |

8–9 |

Elevated pH, often via minerals or electrolysis |

Strongly alkaline research water |

Up to about 10.0 |

Used in some clinical and sports studies |

Blood |

About 7.35–7.45 |

Tightly regulated; only tiny deviations are tolerated |

Stomach fluid |

About 1.5–3.5 |

Strong acid needed for digestion |

Bile and pancreatic juices |

Around 8.0 |

Alkaline, neutralizing stomach acid in the small intestine |

The key takeaway is that pH naturally varies from place to place, and the body works constantly to keep blood pH in a very narrow, slightly alkaline window.

How Your Body Regulates Blood pH

Multiple reputable organizations in these notes, including MD Anderson Cancer Center, the American Institute for Cancer Research, and Harvard Health, all stress the same point: your lungs and kidneys guard blood pH fiercely.

Normal blood pH sits in a narrow alkaline range of roughly 7.35 to 7.45. The lungs adjust carbon dioxide, which behaves like an acid in the blood. The kidneys excrete extra acid or base in urine. Together, they keep blood pH steady, even when meals and drinks vary in acidity. MD Anderson explains that any acidic or alkaline components from foods and medications are quickly filtered out and excreted so that blood pH remains stable.

Several sources note that significant, sustained deviations in blood pH are medical emergencies. The WebMD and GoodRx summaries included in the notes highlight that blood pH values below about 6.8 or above about 7.8 can be fatal. Clinicians call these states acidosis or alkalosis, and they are usually driven by serious diseases, not by normal eating or drinking.

Urine pH, on the other hand, can vary a lot. Both the American Institute for Cancer Research and MD Anderson explain that your body uses urine (and to a lesser extent saliva and sweat) as a “dumping ground” for excess acids and bases. That is why an “alkaline diet” or alkaline water can raise urine pH, without meaningfully changing blood pH. Testing urine pH at home does not give a reliable window into blood pH or cancer risk.

When I evaluate a client’s hydration plan, this physiology is my starting point. The question is never “How do we make your blood alkaline?” It is “How can we support the systems that already keep your blood pH where it belongs?”

What Counts As Alkaline Water?

Definition And How It Is Made

Across the research notes, alkaline water is consistently defined as drinking water with a pH above 7, typically around 8 to 9, and in some research settings up to about pH 10. Articles from Mayo Clinic, Harvard Health, and multiple nutrition and arthritis organizations all use that same basic definition.

Alkaline water can be created in several ways.

Some products are naturally alkaline because spring water has flowed over mineral‑rich rocks and picked up minerals such as calcium, magnesium, potassium, and sodium. Others are produced by machines that perform electrolysis or ion exchange, separating acidic and alkaline components of water and raising the pH on the drinking side. News‑Medical also describes “alkaline reduced water” generated from mineral sources such as calcium and magnesium, often in conjunction with electrolysis.

In home and workplace filtration systems, I often see reverse osmosis units that strip water down to nearly zero minerals, then a remineralization cartridge adds back a controlled blend of minerals. Depending on the design, the final water may be very close to neutral or slightly alkaline.

Alkaline Water Versus Mineral Water Versus Purified Water

It is important to distinguish between pH and mineral content. A Culligan Quench overview notes that alkaline water often has higher levels of minerals like calcium and magnesium than purified waters, and that those minerals are part of its appeal. However, many medical reviews (including GoodRx and Verywell Health) point out that the actual mineral amounts per serving are usually small enough that nutrition labels list them as “not a significant source of nutrients.”

At the same time, some clinical trials in the research notes used waters that were both alkaline and quite rich in bicarbonate and other minerals. A German randomized trial, for example, compared four mineral waters that differed substantially in bicarbonate content and in their “potential renal acid load” (PRAL), an index of how acidic or alkaline‑forming a drink is for the kidneys. Waters with high bicarbonate and strongly negative PRAL values acted as more potent alkalinizing agents at the kidney level, even if the difference in pH number on the label might not look dramatic to a consumer.

That distinction matters when we ask what alkaline water can realistically do to blood pH.

Can Drinking Alkaline Water Change Your Blood pH?

The Popular Theory

The theory behind alkaline water’s pH effects seems intuitive. Since blood and body tissues are mostly water, and alkaline water has a higher pH than regular water, drinking enough of it should make the body more alkaline. That is the story commonly told on marketing materials and some wellness blogs.

Articles from the Cooper Institute and other sources in the notes describe this logic explicitly: because 60 to 70 percent of adult body weight is water and blood has a high water content, people assume alkaline water will make blood less acidic. Some brands even go further, suggesting that alkaline water can help prevent cancer, slow aging, or “detoxify” the body.

However, physiologists interviewed by consumer‑protection groups such as the Center for Science in the Public Interest emphasize another perspective. They note that the average person has roughly 30 to 50 liters of water distributed in body tissues. Compared to that, drinking about a quart of alkaline water is literally a drop in the bucket. Any small shift in fluid pH is quickly buffered and corrected by the lungs and kidneys.

So where does the latest research land between marketing and skepticism?

Evidence That Alkaline Water Can Nudge Acid–Base Markers

Several well‑designed studies in the notes looked directly at acid–base balance in people drinking alkaline or bicarbonate‑rich waters.

One trial, published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, followed healthy college‑aged adults over several weeks. Everyone first drank a low‑mineral, neutral‑pH bottled water to establish their own baseline. Then, for two weeks, one group replaced their usual intake with a mineral‑based alkaline bottled water with a pH of 10, while the control group continued with the neutral water. The waters were matched for osmolality and looked similar, and the study used fingertip blood samples and pooled 24‑hour urine collections to track pH and hydration markers.

According to the authors’ analysis, two weeks of drinking the high‑pH mineral water resulted in statistically significant increases in both blood pH and urine pH, along with reductions in urine osmolality, in the alkaline‑water group. The control group drinking low‑mineral water showed little or no change. The authors interpreted these changes as a more alkaline internal environment and improved hydration status in otherwise healthy young adults.

Another randomized controlled trial in Germany studied 129 healthy adults who drank around 1.5 to 2.0 liters per day of one assigned mineral water for four weeks while keeping their usual omnivorous diet. The waters differed mainly in bicarbonate content and PRAL. Bicarbonate‑rich waters with clearly negative PRAL values produced substantial reductions in net acid excretion, which is a kidney marker indicating a lower net acid load. Those same waters produced small but measurable increases in serum bicarbonate. The low‑bicarbonate, positive‑PRAL water did not.

The authors of that trial concluded that regularly drinking about 1.5 to 2.0 liters per day, roughly 50 to 70 fluid ounces, of bicarbonate‑rich, negative‑PRAL mineral water can effectively lower diet‑related net acid load under everyday conditions, and may help mitigate what they call low‑grade metabolic acidosis associated with typical Western eating patterns.

Taken together, these trials show that when people replace their habitual water with specific types of mineral‑rich, high‑pH water, laboratory markers such as blood pH, serum bicarbonate, urine pH, and net acid excretion can move toward a more alkaline profile. Importantly, these shifts still remain within the normal physiological range; participants remained healthy and no one “overshot” into dangerous alkalosis.

From a practical hydration standpoint, this tells me that some alkaline or bicarbonate‑rich waters can modestly ease the acid load the kidneys handle every day, especially when the rest of the diet is relatively acid‑producing.

Why Experts Still Say You Cannot “Alkalize Your Blood” In A Big Way

The same body of evidence also supports a second, equally important conclusion: these changes are modest, tightly controlled, and do not justify the claim that people can dramatically “alkalize their blood” simply by drinking alkaline water.

Harvard Health, Mayo Clinic, MD Anderson Cancer Center, the American Institute for Cancer Research, and arthritis and nutrition organizations quoted in the research notes all repeat a consistent message. In healthy individuals, the lungs and kidneys keep blood pH within the narrow range around 7.4 regardless of whether the diet is more acidic or alkaline‑forming. Diet and water intake can change how much acid the kidneys excrete (and therefore urine pH), but blood pH itself does not swing wildly with food choices.

One GoodRx medical review cited in the notes goes even further in the specific context of kidney stone prevention. It concludes that the alkali content of typical alkaline waters is too low to meaningfully raise urinary pH the way prescription agents like potassium citrate do, and that alkaline water does not meaningfully change blood pH. In other words, even if some high‑bicarbonate waters can shift acid–base markers, many everyday “alkaline waters” sold at the grocery store may not be potent enough to reproduce those effects.

This is not a contradiction so much as a scale issue. Research‑grade waters with carefully controlled mineral loads, consumed consistently at volumes around two quarts per day, can nudge acid–base chemistry in a measurable way. The everyday reality of someone grabbing an occasional bottle of pH 8.5 water on top of a high‑salt, high‑protein diet is very different.

As a hydration specialist, the way I frame this for clients is simple.

Alkaline water is not a tool for overriding your body’s pH controls. At best, certain mineral waters can mildly lighten the kidneys’ acid‑handling workload and provide very small shifts in blood chemistry that remain within normal limits. That is very different from turning an “acidic body” into an “alkaline body.”

Urine pH, Dietary Acid Load, And Where Alkaline Water Has Clearer Effects

The Concept Of Dietary Acid Load And PRAL

One of the most useful frameworks in the research notes is potential renal acid load, or PRAL. This calculation uses protein and mineral intakes, particularly phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, and calcium, to estimate whether a food or drink will be net acid‑forming or base‑forming for the kidneys.

A trial published in a nutrition journal on mineral waters and acid–base status explains that a typical Western diet, heavy in processed grains and animal products and relatively low in fruits and vegetables, tends to be net acid‑producing. This chronic, diet‑induced acid burden may contribute to what the authors call low‑grade metabolic acidosis, a subtle, long‑term shift that still keeps blood pH technically normal but increases the workload on the kidneys and may be linked to bone loss, urinary stones, and cardiometabolic risks.

In that context, waters with strongly negative PRAL values act like base‑forming foods. The German trial described earlier showed that bicarbonate‑rich waters with medium or strongly negative PRAL values reduced net acid excretion by almost half or more compared with baseline, whereas a low‑bicarbonate, positive‑PRAL water did not.

So while your overall diet does the heavy lifting, water choice can play a supporting role in modulating acid load at the level of the kidneys.

Urine pH: A Real, But Limited, Target

Several sources in the notes underline that urine pH is the main place where alkaline water clearly has an effect. The sports nutrition trial found higher urine pH and lower urine osmolality after two weeks on high‑pH water. The mineral water trial found lower net acid excretion and small rises in serum bicarbonate. News‑Medical’s review of alkaline ionized water describes improvements in melamine excretion in experimental urinary bladder stone models and hints at potential roles in specific kidney‑related conditions.

At the same time, urologists and cancer nutrition experts quoted by MD Anderson and the American Institute for Cancer Research caution against over‑interpreting urine pH as a marker of overall health or cancer risk. A more alkaline urine largely means your kidneys are excreting more base or fewer acids to keep blood pH steady. It does not mean tumors are being starved of acid or that blood pH is changing dramatically.

Realistically, that means two things. First, alkaline or bicarbonate‑rich mineral waters can be useful tools when a physician is intentionally targeting urine chemistry, as in some kidney stone protocols. Second, for everyday wellness, the goal is not chasing a particular urine pH number with test strips, but reducing net acid load through both diet and, where appropriate, water choice.

Alkaline Water, Disease Claims, And What The Evidence Really Shows

Cancer, “Acidic Bodies,” And The Alkaline Myth

Marketing often leans hard on the idea that cancer cells “thrive in acid,” and that an alkaline diet or alkaline water can prevent or even cure cancer. The research notes include strongly worded rebuttals from both the American Institute for Cancer Research and MD Anderson Cancer Center.

These cancer experts explain that while some lab experiments show tumor cells living in acidic microenvironments, that acidity is usually produced by the tumor itself as it grows and alters local metabolism.

It is not created by a person’s “acidic diet.” More importantly, there is no reliable evidence that changing what you eat or drink can meaningfully alter the pH inside a tumor or that an alkaline diet or alkaline water can treat or cure cancer.

Both organizations emphasize that blood pH stays tightly controlled and does not shift into a broadly alkaline state from diet. They also note that cancers can arise in tissues with many different normal pH levels, from the very acidic stomach to the more alkaline pancreas, which contradicts the simplistic idea that an “alkaline body” is immune to cancer.

Where the alkaline diet does align with evidence is in the foods it encourages. Emphasizing vegetables, fruits, beans, whole grains, and limiting processed foods and alcohol is firmly supported by large epidemiologic studies for cancer prevention. Those benefits come from fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytochemicals, not from changing pH.

Metabolic Health, Bone, Reflux, And Hydration

Beyond cancer, the research notes summarize several smaller studies suggesting potential benefits of alkaline water or bicarbonate‑rich mineral waters in specific areas.

A cross‑sectional study among 304 postmenopausal women in Malaysia compared regular alkaline‑water drinkers, defined as consuming at least about a quart of alkaline water per day for two months or more, with non‑drinkers. The alkaline water in that study was generated via alkaline balls and nanofiltration to retain certain minerals such as calcium and magnesium. Overall, about 47.7 percent of participants met criteria for metabolic syndrome, but the prevalence was significantly lower among alkaline‑water drinkers. They also had lower fasting plasma glucose, a lower triglyceride to HDL‑cholesterol ratio, lower diastolic blood pressure, and smaller waist circumference, along with longer sleep duration and higher handgrip strength. Other markers like LDL cholesterol, body weight, and systolic blood pressure did not differ. The authors emphasize that this was an observational snapshot, not a trial, so the findings show associations rather than proof of cause and effect.

For bone health, the Arthritis Foundation notes a small trial in people with osteoporosis where those who drank around six cups per day of alkaline water along with standard calcium, vitamin D, and a weekly bone medication saw greater spine bone density gains over three months than those on medications and supplements alone. Animal research has reported similar bone benefits, although mechanisms remain unclear and longer studies in humans are needed.

On reflux, several sources highlight a laboratory study showing that water around pH 8.8 can permanently neutralize pepsin, a key enzyme implicated in laryngopharyngeal reflux. A trial in patients with reflux disease found that a Mediterranean‑style, mostly plant‑based diet plus alkaline water controlled symptoms about as well as proton pump inhibitor medications, although diet likely drove much of the benefit. Arthritis and rheumatology organizations reviewing this evidence consider alkaline water a potentially reasonable adjunct for some patients seeking non‑drug approaches, but not a replacement for medical evaluation.

In hydration and performance, the sports nutrition trial mentioned earlier found that mineral‑based high‑pH water reduced urine osmolality and increased urine and blood pH after exercise, consistent with better hydration and a more alkaline acid–base profile. Another sports nutrition study referenced by WebMD and News‑Medical reported that electrolyzed high‑pH water reduced whole‑blood viscosity in healthy adults after exercise‑induced dehydration. These studies are promising but small, and they focus on surrogate markers rather than long‑term health outcomes.

From a Smart Hydration Specialist’s viewpoint, I take these signals seriously but keep them in context. In homes and offices, alkaline or bicarbonate‑rich water may be a sensible upgrade for people already working on diet and lifestyle, especially where bone health, kidney stone risk, or reflux are concerns under medical supervision. It is not a stand‑alone cure.

Safety Considerations And Who Should Be Cautious

Most sources in the research notes agree that, for healthy adults, drinking moderate amounts of commercially available alkaline water within normal drinking‑water standards appears safe. However, there are reasonable cautions.

News‑Medical, drawing on World Health Organization drinking water guidelines, notes that water with a pH above 9 can cause skin and eye irritation in animal models, and that pH above 10 in humans can irritate skin, eyes, mucous membranes, and potentially the gastrointestinal tract in sensitive individuals. Harvard Health and arthritis organizations also warn that strongly alkaline water can taste bitter and may raise stomach pH enough to interfere with normal digestion, particularly in people already taking proton pump inhibitor medications that reduce stomach acid.

Both Mayo Clinic and Verywell Health highlight that individuals with chronic kidney disease or those on medications that affect kidney function should be cautious with high‑mineral alkaline waters, because altered mineral handling could theoretically lead to imbalances. GoodRx and Verywell Health also mention that homemade alkaline water using baking soda can shift electrolytes in unsafe ways if overused, especially in people with kidney or heart issues.

Finally, News‑Medical raises an emerging concern specific to electrolysis‑based devices: electrode degradation can release reactive platinum nanoparticles into the water, which may have toxic effects. This underscores the importance of high‑quality manufacturing and certification for in‑home ionizer devices.

In my practice, I encourage anyone with kidney disease, significant reflux, or complex medication regimens to discuss alkaline water with their healthcare team before installing an ionizer or drinking large volumes of high‑pH water daily.

Practical Guidance: Choosing Water When You Care About Blood pH

Focus First On Hydration And Water Quality

A research brief from a national health library summarized in the notes reminds us that, from a public‑health standpoint, the priorities are adequate hydration and safe water, regardless of type. Common intake guidance cited there suggests that men generally need around fifteen cups of fluids per day and women about eleven cups, from all beverages and water‑rich foods combined. The exact number varies with climate, activity, and health status, but the principle is simple: being consistently well‑hydrated matters more for most outcomes than tweaking water pH.

For homes and offices, that means starting with a system that delivers reliably clean, good‑tasting water that people actually like to drink, whether that is a high‑quality under‑sink filter, a point‑of‑use dispenser, or a properly maintained bottled system. If a neutral‑pH filtered water encourages more consistent sipping throughout the day than a more exotic option, that may be the healthier choice.

When Alkaline Or Mineral Water Might Make Sense

For healthy people who like the taste and feel better drinking alkaline or mineral water, the research suggests it is reasonable to enjoy it as part of everyday hydration, provided the product stays within accepted drinking‑water pH ranges and is sourced or produced safely. In particular, bicarbonate‑rich mineral waters with negative PRAL values, consumed at volumes around fifty to seventy fluid ounces per day, have been shown to reduce net acid excretion and slightly raise serum bicarbonate, which may help buffer the acid load of a typical Western diet.

In my work designing hydration systems, I often recommend a remineralizing filter or a moderate‑alkalinity cartridge when a client wants water that tastes a bit smoother and less “flat” than pure reverse osmosis water. The goal there is not to push pH to extremes, but to reintroduce modest levels of calcium and magnesium and land in a mildly alkaline range that supports both taste and equipment longevity.

For people working with a healthcare professional on kidney stones, bone density, or reflux, alkaline or bicarbonate‑rich waters can be one part of a broader strategy that also includes diet, medications, and other lifestyle measures. The clinical trials in the notes suggest there may be incremental benefits in these scenarios, although the evidence base is still developing.

When To Be Skeptical Or Cautious

If a product or influencer claims that alkaline water will dramatically change blood pH, cure cancer, melt away fat, or reverse aging, the evidence summarized in these research notes does not support those promises. Major health organizations mentioned here, including cancer centers and national heart and diabetes groups, do not endorse alkaline water for disease prevention or cure.

From a cost–benefit perspective, several consumer‑oriented reviews point out that bottled alkaline water often costs at least twice as much as regular bottled water, while tap water paired with a good filter remains far more economical and environmentally friendly. In many homes and workplaces I advise, shifting budget from premium bottled alkaline water into a robust filtration and remineralization system yields better hydration habits and less plastic waste without chasing unproven health claims.

People with chronic kidney disease, those on complex medication regimens, and individuals who already have reduced stomach acid from medications should treat high‑pH or high‑mineral products as something to clear with their clinician rather than self‑prescribing them based on marketing.

A Brief FAQ On Alkaline Water And Blood pH

Can alkaline water “fix” an acidic body?

The controlled studies in the research notes show that certain bicarbonate‑rich, high‑pH waters can modestly increase blood pH or serum bicarbonate within the normal range and reduce kidney net acid excretion. However, major medical organizations emphasize that in healthy people the body already keeps blood pH tightly regulated between about 7.35 and 7.45. Alkaline water can support the kidneys’ workload and may shift some lab markers, but it does not transform an “acidic body” into an alkaline one in any dramatic or permanent way.

If my urine pH becomes more alkaline after drinking alkaline water, does that mean my blood pH changed?

Not necessarily. As MD Anderson Cancer Center and the American Institute for Cancer Research explain, urine is one of the main routes the body uses to excrete excess acids or bases while protecting blood pH. When diet or water intake becomes more alkaline‑forming, the kidneys can send more base into the urine, raising urine pH. That is a sign that your kidneys are doing their job, not proof that blood or tissue pH has changed in a clinically meaningful way.

Is it worth installing an alkaline water system at home purely for blood pH?

If your only goal is to change blood pH, the answer from current evidence is no. The small shifts documented in clinical trials occur within the normal range and are not a substitute for treating underlying diseases that disturb acid–base balance. However, if you enjoy the taste of mildly alkaline, mineralized water, if your diet is heavy in acid‑forming foods, or if your clinician has suggested a bicarbonate‑rich water as part of a kidney, bone, or reflux management plan, then a well‑designed remineralizing or alkaline‑leaning system can be a sensible component of an overall hydration strategy.

In the end, your blood pH is less a knob you can turn with a beverage and more a vital sign your body protects around the clock. Thoughtful use of alkaline or bicarbonate‑rich waters can support hydration and gently influence acid–base markers, but the foundations remain the same: clean water you enjoy drinking, a plant‑forward eating pattern, and a lifestyle that respects the remarkable chemistry your body already manages for you.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/94122417/Alkaline_Water_and_Human_Health_Significant_Hypothesize

- https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/is-alkaline-water-better

- https://jdc.jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=student_papers

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6901030/

- https://www.logan.edu/mm/files/LRC/Senior-Research/2006-Aug-17.pdf

- https://www.chemedx.org/blog/can-alkaline-water-change-body-ph

- https://www.cooperinstitute.org/blog/alkaline-water

- https://www.mdanderson.org/cancerwise/alkaline-diet--what-cancer-patients-should-know.h00-159223356.html

- https://www.cspi.org/daily/what-not-to-eat/what-can-alkaline-water-do-for-you

- https://www.aicr.org/resources/blog/does-the-alkaline-diet-cure-cancer/

Share:

Understanding the Truth Behind Bottled Water RO Systems

Understanding Why Bartenders Prioritize Water Quality Over Alcohol