As a Smart Hydration Specialist and water wellness advocate, one of the most common frustrations I hear from homeowners is this: “Something is wrong with my water, but I don’t know if I should call a lab, my plumber, or my filtration company.” Cloudy glasses, rusty stains, odd tastes, and sputtering faucets can come from two very different places. Sometimes the problem is the water itself. Other times, your well, plumbing, or filtration system is simply not doing its job.

Distinguishing a genuine water quality issue from an equipment malfunction is not just a technical exercise. It affects your family’s health, your maintenance budget, and how confident you feel every time you fill a glass. The good news is that you do not need to become a chemist to make smart decisions. You do, however, need a basic framework for reading the signs, and a willingness to pair those signs with simple testing and system checks.

In this article, we will use science-backed guidance from organizations such as the CDC, EPA, Atlas Scientific, Sensorex, Penn State Extension, and multiple water treatment and pump experts to help you tell the difference and act decisively.

Two Different Problems That Often Look The Same

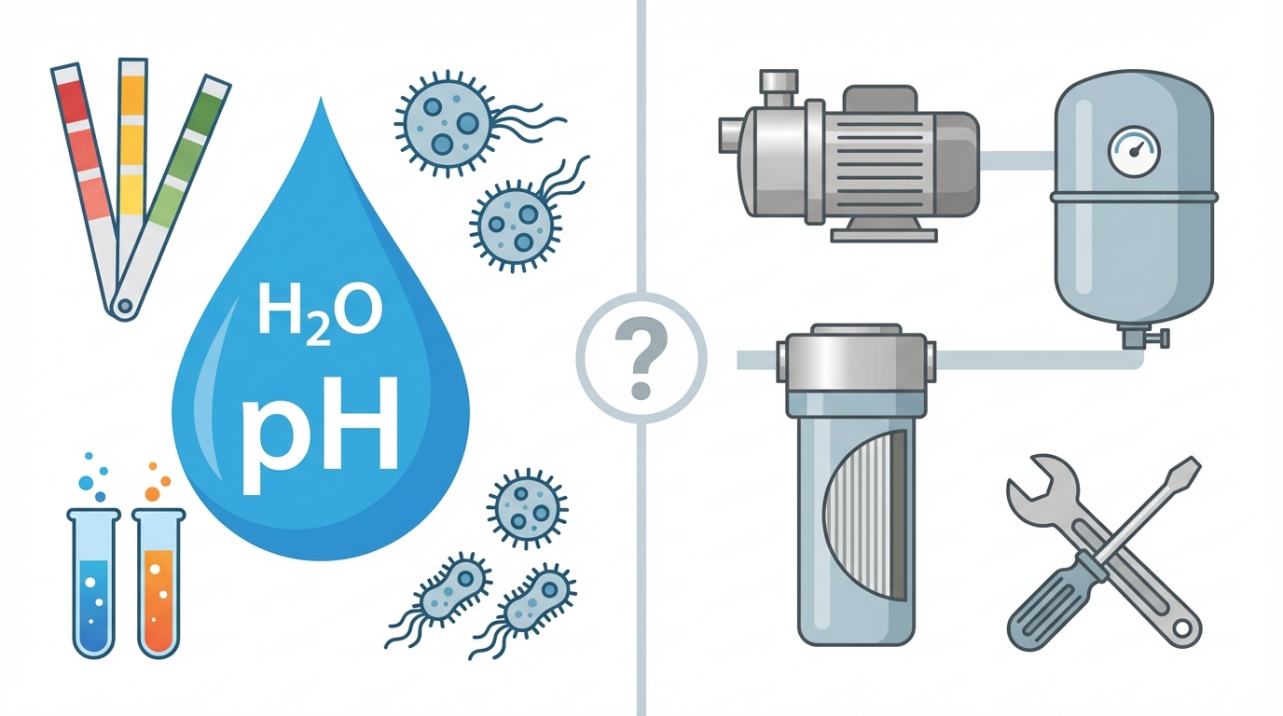

At a high level, nearly every “mystery water issue” at home falls into one of two categories: a water quality problem or an equipment problem. Understanding the difference is your starting point for smart troubleshooting.

What Counts As A Water Quality Issue?

Water quality is about what is in the water, not how your equipment behaves. Atlas Scientific describes water analysis as measuring physical, chemical, and biological properties to determine whether water is safe and suitable for a specific use. Sensorex and Aquaread make the same point: quality depends on parameters such as turbidity (cloudiness), pH, dissolved solids, color, temperature, bacteria, and specific contaminants like metals or nutrients.

Penn State Extension explains that water test reports usually group parameters into three roles. Some parameters are health-related, such as bacteria, nitrates, or certain metals. Others are general indicators, like turbidity or pH, which hint that other contaminants might be present. A third group are nuisance parameters, such as hardness or iron, which mostly affect taste, staining, and scale even when they are not a direct health threat.

The CDC notes that private well owners should test at least annually for total coliform bacteria, nitrates, total dissolved solids, and pH. These are not always dangerous on their own, but they alert you that germs or chemicals from sewage, agricultural runoff, or other sources may be getting into your water. In some areas, health or environmental agencies recommend additional tests for volatile organic compounds, heavy metals, or pesticides.

In short, you are dealing with a water quality issue when your source water itself contains dissolved or suspended substances that exceed health guidelines or aesthetic standards, even if your equipment is working perfectly.

What Counts As An Equipment Malfunction?

Equipment issues are mechanical, hydraulic, or electronic faults in the systems that move or treat your water: pumps, pressure tanks, filtration units, softeners, and plumbing.

Residential well experts from Clean Water Store and pump specialists describe classic equipment problems such as:

• Pumps that short-cycle on and off because of a failed check valve or exhausted pressure tank. • Wells that start pumping air or sand due to a dropping water table, damaged drop pipe, or a failing well screen. • Water treatment units that lose pressure or leak because filter cartridges are clogged or seals are worn. • Filtration systems that slow to a trickle or make odd noises when media is exhausted or installation is poor.

Industrial water and wastewater operators report similar themes. Veolia, Lakeside Equipment, Membracon, and Chesterton all highlight reliability drops, rising energy use, pressure changes, leaks, and abnormal vibration as early equipment red flags, even when incoming water quality has not changed.

You are dealing with an equipment malfunction when the hardware that should move or improve your water is underperforming, regardless of whether the source water is clean or contaminated.

To keep these ideas straight, it can help to see them side by side.

Symptom Focus |

Typical “Water Quality” Issue |

Typical “Equipment” Issue |

What is wrong |

Contaminants, pH, turbidity, microbes |

Pump, filters, valves, sensors, plumbing |

Where you measure |

Lab testing, at-home test kits, meters |

Flow, pressure, noises, leaks, control behavior |

Primary risk |

Health, taste/odor, staining, scale |

Loss of treatment, damage, downtime, higher bills |

Typical response |

Testing, source protection, treatment design |

Maintenance, repair, replacement, reconfiguration |

Understanding Your Water Numbers So You Do Not Misread The Signs

Because the same symptom can come from water or equipment, numbers matter. You do not need to memorize all the parameters, but understanding a few key ones will help you recognize when a test result points to the water itself rather than to your system.

Sensorex and Atlas Scientific divide water quality parameters into physical, chemical, and biological groups. Physical parameters include turbidity, temperature, color, and electrical conductivity. Chemical parameters include pH, hardness, chlorine, acidity, alkalinity, and dissolved oxygen. Biological parameters cover bacteria, algae, and viruses.

Penn State Extension explains that many parameters are reported in milligrams per liter, which is essentially the same as parts per million. They offer a helpful analogy: one part per million is roughly the amount of about three hundredths of a teaspoon of sugar in a bathtub full of water. That gives you a sense of how small these numbers are, even when they have real effects.

For hardness, Penn State notes that results may be shown either in milligrams per liter or in grains per gallon, and that about 17 milligrams per liter equals one grain per gallon. CWQA indicates that scale problems often begin around three and a half grains per gallon. If your test report lists hardness as 180 milligrams per liter, you can divide 180 by 17 and see that your water is roughly ten and a half grains per gallon. That level is considered very hard and is likely to create significant scale and soap scum, regardless of how new your fixtures are.

Sensorex also describes how total dissolved solids and conductivity relate to overall mineral content. Freshwater typically has less than about 1,500 milligrams per liter of dissolved solids. As levels rise toward brackish or saline ranges, taste and corrosion behavior change, and treatment becomes more challenging.

On the biological side, the CDC explains that total coliform bacteria serve as a general indicator of contamination and that fecal coliform or E. coli indicate fecal pollution. A positive E. coli result means the water is not safe to drink without treatment, even if everything looks clear and tastes normal.

When you see a lab report with high hardness, high iron, elevated manganese, or bacteria present, those numbers point to water quality issues.

When the lab report looks similar to earlier tests but your water suddenly turns cloudy or your pressure drops, that pattern suggests an equipment or plumbing issue instead.

Symptom By Symptom: Is It The Water Or The Equipment?

The fastest way to build intuition is to walk through the common complaints people have about their water and see how likely each one is to be caused by source water versus equipment.

Stains, Scale, And Cloudy Dishes: Hardness Versus Failing Softener

CWQA notes that yellow, brown, or rusty stains on fixtures are often linked to elevated iron in water, and that stains can appear even when the water coming out of the tap looks clear. They report that iron above about 0.3 parts per million is enough to cause noticeable staining, especially when water oxidizes on contact with air. They also note that black stains often point to manganese at levels above about 0.05 parts per million. Both are primarily aesthetic concerns in their guidance, though research is ongoing for manganese.

Hard water shows up differently. Both CWQA and Penn State Extension describe hardness as dissolved calcium and magnesium. CWQA reports that once hardness reaches about three and a half grains per gallon or more, you start to see scale buildup in pipes and on glassware, spots on dishes, and more soap and detergent use. Laundry can look gray and dingy, and skin and hair can feel filmy. Weeks Drilling points out that hard water affects a large majority of households in the United States, and they highlight how it drives scale, appliance inefficiency, and higher energy bills.

Those are classic water quality signals. But a failing softener or filter can make the same symptoms appear suddenly even if your water source has not changed. Pilot Plumbing notes that when filtration media is exhausted, metallic-tasting water and hard water symptoms return because the system is no longer effectively reducing metals and minerals. Fussell Well Drilling explains that visible mineral stains and scale on fixtures after you already have a treatment system in place often mean the system is no longer keeping up.

A simple way to separate the two causes is to compare hardness and iron before and after your treatment system. If a lab report shows raw well water hardness at 180 milligrams per liter, which is roughly ten and a half grains per gallon, and a sample taken before your softener consistently tests that high, the source water is clearly hard. If a sample taken after the softener had previously tested at, say, one or two grains per gallon but now tests at eight or nine, that change points to exhausted resin or a control problem rather than a sudden change in the aquifer.

In practical terms, gradual staining that matches long-term lab results usually reflects source water quality. A sudden increase in staining in a home that already has a softener or iron filter, especially if it appears soon after you skip maintenance or notice low salt levels, usually reflects an equipment issue.

Taste And Odor Changes: Contaminants Versus Exhausted Filters

Chemical attributes such as how water looks, smells, and tastes are a primary way Aquaread suggests identifying water quality issues. Sensorex adds that disinfectants like chlorine, while important for public health, can leave distinct tastes and odors if not managed properly.

Penn State Extension calls iron bacteria, hydrogen sulfide, and hardness classic nuisance contaminants. They may not be health hazards at typical levels, but they can cause rotten egg odors, metallic tastes, and soap performance issues. Weeks Drilling notes that chlorine and chloramine used in public systems can leave noticeable taste and odor, while sulfur and iron contribute to off-flavors and staining.

At the same time, equipment failures can produce very similar sensory changes. Pilot Plumbing reports that metallic-tasting water can signal that filter media is no longer reducing metals and minerals effectively. They also note that noticeable sulfur or chlorine odors reappearing in tap water can mean the filtration system is no longer adequately removing those chemicals. Fussell Well Drilling adds that sudden changes in taste, odor, or clarity often point to saturated filters, worn internal components, or new contamination that your existing setup was not designed to handle.

Here is how to think it through. If you are on a private well, and both you and your neighbors who share the aquifer suddenly notice a new sulfur smell, that pattern points to a change in source water quality. In that case, the CDC would advise immediate testing for key health parameters and, depending on local guidance, possible additional chemical tests. On the other hand, if only the kitchen sink connected to a small under-sink filter smells strongly of chlorine while the bathroom tap upstream of the filter smells normal, the filter itself is the first suspect.

A practical example helps. Imagine your water analysis report last year showed no coliform bacteria, nitrates below local guidelines, hardness around six grains per gallon, and no hydrogen sulfide odor. Your point-of-use filter is rated to last six months, but after a year you start tasting chlorine again and see the manufacturer’s indicator light turn on. The underlying water quality numbers have not changed, but the sensory experience has. In that situation, replacing or upgrading the filter is the priority, not redesigning your entire treatment train.

Discolored Water Or Visible Particles: Source Disturbance, Corrosion, Or Media Breakdown

Discoloration and visible particles often alarm people, and rightly so. CWQA emphasizes that even clear water can leave stains when iron or manganese oxidize, but obvious brown, yellow, or black water can appear after disturbances as well. Clean Water Store notes that wells that suddenly start pumping sand or heavy sediment may be silting in, may have pumps placed too close to the bottom, or may suffer from failing well screens. Sand not only makes the water unsightly, it rapidly wears out pump components.

Environmental agencies and outreach pieces on local waterways describe discolored, murky water and surface scum as classic signs of pollution or high sediment loads. Those signs matter more for lakes and rivers than for a kitchen tap, but they reinforce the idea that color often means something has changed in the waterway itself.

Inside the home, you also have to consider plumbing and filters. Over time, aging metal pipes can corrode internally, releasing rust particles that tint the water, particularly when you first open a tap after the water has been sitting. Granular activated carbon filters can shed fine black particles when they are new or when the media bed is disturbed, which looks alarming but is usually an equipment artifact rather than a new contaminant source.

If you are on a well and you suddenly see gritty sand in every faucet, and your pump begins to run longer and louder, Clean Water Store’s experience suggests a well or pump problem. That is an equipment and infrastructure issue that requires a well or pump contractor, even though the symptom appears to be “in the water.” By contrast, if your raw water test shows high iron but your treated water was clear until your iron filter stopped being serviced, the equipment is likely failing to remove an existing water quality problem.

One practical diagnostic step is to collect separate samples from upstream and downstream of major pieces of equipment, such as before and after a softener or whole-house filter. If both samples are discolored with similar particles, the issue likely lies in the source water or plumbing. If the upstream sample is clear while the downstream sample contains media-like grains, the filter itself becomes the prime suspect.

Low Pressure And Slow Flow: Plumbing, Pump, Or Plugged Filters?

Low pressure can feel like a water quality issue because the experience at the tap is poor, but it is almost always equipment related. Pump Supplies points to clogged pipes, damaged impellers, and air pockets as common causes of low pump pressure. Clean Water Store describes a wide range of well-related pressure problems: failing pumps, stuck check valves, leaking or failing pressure tanks, and clogged pressure-sensing nipples. Veolia highlights decreased system efficiency and reduced flow in industrial plants as clear signs that a treatment system needs maintenance or upgrades.

On the filtration side, Pilot Plumbing notes that slow filtration and reduced faucet flow are early signs that filters are clogged with sediment or biofilm. Fussell Well Drilling explains that reduced water pressure throughout the home often comes from clogged filters or mineral and sediment buildup in plumbing connected to treatment equipment.

To separate these causes, think about where the pressure drop occurs. If every faucet in your house, including an outdoor spigot upstream of any filters, has very low pressure, the problem is likely at the pump, pressure tank, or main plumbing. Clean Water Store’s guidance shows that if your pump is short-cycling or your power bill has skyrocketed while pressure falls, equipment issues such as a failing check valve or fouled pump become highly likely.

If, on the other hand, only the filtered circuits are slow while an unfiltered bathroom tap has normal pressure, plugged cartridges or fouled membranes are the better bet. Fussell Well Drilling recommends that when a pressure tank is involved, you confirm that the tank still has the correct air charge, typically a couple of pounds per square inch below the cut-in pressure of the switch. They describe a simple process of turning off the pump, relieving pressure, and using a tire gauge on the tank’s Schrader valve.

A homeowner-friendly way to quantify the issue is to time how long it takes to fill a one-gallon container from an upstream tap and from a downstream tap. If the upstream tap fills the container in, say, fifteen seconds while the filtered tap takes a full minute, your equipment is creating a large pressure drop, even if overall system pressure is acceptable.

Strange Noises, Leaks, And Cycling: Almost Always Equipment

Noise, leaks, and odd cycling patterns are some of the clearest signs that something mechanical needs attention. Pump Supplies lists overheating, leakage, noisy operation, and cavitation as common pump problems, each with distinct sounds and symptoms. Clean Water Store describes pumps that run nearly nonstop because of failed check valves or tank issues, driving energy bills up while wearing equipment out.

For treatment systems, Pilot Plumbing warns about recurring odd noises from faucets and low pressure caused by clogged filters, and they describe cracked or burst filters in winter when water inside freezes. Fussell Well Drilling calls out gurgling, hissing, or clanking sounds in treatment units as signals of trapped air, malfunctioning pumps, or clogged filters that need professional diagnosis.

On the industrial side, Lakeside Equipment and Chesterton stress continuous monitoring of vibration, temperature, and pressure as a way to catch seal failures, lubrication issues, and clogged components before they cause full breakdowns. Although their examples come from larger plants, the same principles apply to residential equipment. If something starts rattling, banging, or grinding that did not before, it is almost never because the water source itself suddenly changed.

If you hear your pump or filtration system cycling on and off every few minutes even when no fixtures are open, Clean Water Store describes this “short cycling” as a classic sign of a failed check valve or loss of captive air in the pressure tank. That is both an efficiency problem and a reliability risk and should be addressed promptly.

Using Testing And Monitoring To Confirm What Is Really Going On

Symptoms can guide you, but test results and data make the picture much clearer. Multiple sources converge on one simple principle: test the water and monitor your system before you start guessing.

National Water Service defines water quality monitoring as regularly checking physical, chemical, and biological characteristics to ensure water is safe for drinking, cooking, and bathing. For homeowners, they highlight three main tools. You can use at-home kits to screen for basic parameters such as pH, hardness, chlorine, and indicator bacteria. You can send samples to a professional lab for more thorough testing, especially for private wells or when buying a new home. And you can review your public utility’s annual Consumer Confidence Report if you are on municipal water to see what the utility’s own testing shows.

The CDC offers specific guidance for private wells: test at least once a year for total coliform bacteria, nitrates, total dissolved solids, and pH, and test more frequently if there has been flooding, land disturbance, new contamination sources nearby, or noticeable changes in taste, color, or smell. They emphasize using state-certified labs and consulting local health or environmental departments to interpret results and decide on additional tests for chemicals like volatile organic compounds, arsenic, or pesticides.

For more advanced or continuous information, Sper Scientific and Membracon describe the role of online monitors and instrumentation. Sper Scientific discusses continuous meters for pH, turbidity, dissolved oxygen, and temperature that can send alerts when values drift outside set ranges. Membracon focuses on parameters used in membrane systems, such as silt density index, normalized permeate flow, pressure drop, and UV intensity, and stresses the importance of regular record keeping and trend analysis.

In practice, a simple layered approach works well at home. First, pay attention to your senses. If you see or smell something new, treat it as real feedback, not just annoyance. Next, pair that sensory change with basic at-home testing for pH, hardness, chlorine, and perhaps bacteria indicators. Then compare your results and symptoms to any lab reports you have from past years. If the numbers have shifted in the same direction as your symptoms, you likely have a water quality change. If the numbers look stable while the equipment behavior has changed, equipment is the more likely culprit.

A small calculation can put your results in perspective. Suppose your lab report lists total dissolved solids at 600 milligrams per liter and your previous reports hovered around 300. That doubling can signal added minerals, salts, or contamination, and it can influence taste and scale behavior. If at the same time you notice your filter clogging more quickly and your softener regenerating more often, the data and the symptoms both point toward a real change in water quality rather than a random equipment fault.

Practical Decision Scenarios For Home Hydration Systems

Homeowners usually come to me with questions, not parameter lists. Here are three decision scenarios that combine the science and field experience from the sources above into practical guidance.

“My Water Looks And Tastes Fine, But The Lab Found Bacteria. Is That Equipment Or Water?”

When a lab finds total coliform bacteria or E. coli in your sample, the CDC is very clear: this is a water quality problem, and the water is not safe to drink without treatment if E. coli is present. These bacteria come from environmental or fecal contamination, not from mechanical wear. Even though biofilm can grow on equipment surfaces, that growth still traces back to organisms entering with the water.

Your equipment matters here because it might not be providing adequate disinfection or because poorly maintained filters can harbor microbial growth. But the underlying issue is the source water and the pathway that allowed contamination into the well or plumbing. The appropriate response is to stop drinking the water, switch temporarily to bottled or otherwise verified safe water, shock-chlorinate or disinfect the system if recommended, and work with local health agencies and certified professionals to correct the contamination pathway. Simply replacing filters without dealing with the source and the disinfection strategy would not be enough.

“I See Heavy Scale And Spots, But I Also Have A Softener. Do I Call The Lab Or The Softener Company?”

Hardness is one of the clearest examples of the water–equipment interplay. CWQA and Penn State both confirm that hardness levels above about three and a half grains per gallon cause scale, spotting, and extra soap use. Weeks Drilling emphasizes that this is widespread and that water softeners are the primary solution.

If a recent lab report or at-home hardness test shows your raw water is consistently above that threshold, you know the source water is objectively hard.

If your softener is sized and programmed correctly and your treated water tests near one or two grains per gallon, the equipment is doing its job and any minor scale you see may simply reflect higher demand points or older fixtures.

However, if treated water now tests much closer to raw water hardness, if stains appear rapidly on fixtures that used to stay clean, or if the softener is using salt much faster than the manufacturer suggests, the equipment is likely failing or overloaded. In that case, contacting a water treatment professional to check settings, resin condition, and flow rates makes more sense than retesting the source water.

A simple test sequence can clarify things. Test hardness at a hose bib before the softener and at a tap after the softener. If the two numbers are very similar and both are high, the softener is not effectively reducing hardness and needs service. If the raw water hardness is low or moderate but scale is heavy, you may have other issues such as localized heating, stagnant zones, or older plumbing that concentrates minerals.

“My Smart Filter Is Sending Alerts, But My Water Seems Normal. Is This A False Alarm?”

The rise of connected sensors in home hydration systems mirrors what industrial facilities use. Sper Scientific describes how online monitors for pH, turbidity, and dissolved oxygen can detect shifts long before the water looks different. Veolia and Membracon highlight the value of trend data in catching efficiency drops and fouling early.

If your smart filter or inline monitor alerts you to rising turbidity, falling UV intensity, or a spike in total dissolved solids even though your senses do not notice anything yet, treat the alert as useful early information, not an error. Industrial case studies show that waiting until changes are visible can mean you are already dealing with biofilm, fouling, or partial equipment failure.

The best move is to cross-check the alert. Take a grab sample and, if possible, have a lab confirm key parameters. Look at your system’s operational data, such as pressure drop across filters or flow rate changes, if your system exposes them. If both the sensor trend and an independent test show movement in the same direction, schedule maintenance or upgrades before the problem escalates.

When Health Should Override All Equipment Questions

Most home hydration dilemmas are about comfort, taste, and maintenance, but some signs should immediately put you into a health-first mindset.

Aquaread, drawing on global health figures, cites estimates that hundreds of thousands of people die each year due to lack of clean drinking water, and that a large share of illnesses in developing regions trace back to unsafe water and poor sanitation. Weeks Drilling points out that in the United States, concerns now include emerging contaminants such as PFAS in addition to traditional issues like hardness and bacteria.

Penn State Extension distinguishes health-risk parameters from nuisance ones. Health-risk parameters, such as bacteria, nitrates, and certain metals, require immediate attention if they exceed standards. The CDC warns that high nitrates can make people, especially infants, sick and that they often come from animal waste, septic systems, and fertilizers. Atlas Scientific notes that nitrite at high levels can cause serious conditions in infants, including “blue baby syndrome.”

The takeaway is straightforward. If accredited testing shows bacteria, E. coli, nitrates above local limits, or regulated contaminants above their health standards, you are squarely in water quality territory, regardless of how well your equipment is running. Until the contamination is addressed at the source or through robust treatment, your smart hydration system cannot make unsafe water truly safe.

At the same time, equipment failures can turn a manageable water quality situation into a health issue. A carbon filter that is long past its replacement interval or a UV system with a fouled quartz sleeve may let previously controlled contaminants pass through. Membracon shows how UV intensity drop is a critical monitoring point for disinfection units. In these cases, the contamination risk is real even when the source water has not worsened.

Whenever there is a plausible health concern, the safest path is to lean on testing, follow public health guidance, and contact qualified water professionals rather than relying solely on sensory impressions or app notifications.

FAQ

How often should I test my home water if I already have a filtration system?

The CDC recommends that private well owners test for total coliform bacteria, nitrates, total dissolved solids, and pH at least once a year, and more often after flooding, construction, or any noticeable change in taste, color, or smell. National Water Service suggests that even households on public water systems review their utility’s Consumer Confidence Report annually and consider additional testing during real estate transactions or after suspected contamination incidents. Having a filtration system does not replace this baseline. It simply means you should consider testing both raw and treated water to verify that the system is doing what you expect.

Can a failing filter make my water worse than untreated water?

Yes, in practical terms it can. Pilot Plumbing and Fussell Well Drilling both describe situations where clogged or saturated filters reduce flow, shelter microbial growth, or no longer reduce metals, chlorine, or nuisance contaminants effectively. That does not always mean the water is more dangerous than the raw source, but it can be less predictable and more prone to taste, odor, and aesthetic issues. In some cases, such as visible black mold or significant biofilm inside housings, professionals recommend full cleaning, disinfection, and media replacement because the filter itself has become a contamination source.

When should I call a lab versus a plumber or water treatment professional?

Think in terms of what you are trying to learn. If your main question is “What is in my water and is it safe?” then accredited laboratory testing is the right first step, along with guidance from local health or environmental departments. This is especially true when you see health-related indicators such as bacteria, nitrates, or new chemical concerns in your area. If your main question is “Why has my pressure, flow, or equipment behavior changed?” then a plumber, well contractor, or water treatment professional is usually the better starting point. In many cases, the best outcomes come from a combination of both: data from labs and the utility on water quality, paired with on-site diagnostics of pumps, plumbing, and treatment units.

Safe, enjoyable hydration at home depends on both clean source water and reliable, well-maintained equipment. When you understand how to read stains, tastes, odors, pressure changes, and test reports through that dual lens, you stop guessing and start making confident decisions. As a smart hydration specialist and water wellness advocate, my goal is simple: help you use science, monitoring, and thoughtful maintenance so that every glass you pour is not only clear and great-tasting, but also backed by solid evidence that it is truly safe.

References

- https://www.epa.gov/waterdata/assessing-and-reporting-water-quality-questions-and-answers

- https://extension.psu.edu/how-to-interpret-a-water-analysis-report/

- https://www.cdc.gov/drinking-water/safety/guidelines-for-testing-well-water.html

- https://pumpsupplies.co.uk/5-common-problem-of-water-pump-and-solutions/

- https://insidewater.com.au/spotting-the-early-signs-of-equipment-failure-seals-chesterton/

- https://www.csceng.com/water-quality-issues/

- https://everestwater.com/5-common-water-equipment-problems/

- https://www.fussellwelldrilling.com/blog/troubled-waters-common-signs-a-water-treatment-system-needs-a-check-up

- https://www.lakeside-equipment.com/troubleshooting-common-issues/

- https://nationalwaterservice.com/5-ways-to-monitor-my-water-quality/

Share:

Understanding Why Your RO System Sometimes Refuses to Operate

Understanding Why Your Pump Starts But Lacks Pressure