As a Smart Hydration Specialist, I get a steady stream of photos from under-sink cabinets where something has clearly gone very wrong: water on the floor, a drain line that will not stop gurgling, or an RO faucet spitting water out of a mysterious side opening. Many of those situations trace back to one root problem: reverse flow, or “backflow,” inside or around a home reverse osmosis (RO) system.

Backflow is not just a plumbing annoyance. When water moves in the wrong direction it can waste a surprising amount of water, stress expensive components like your membrane, and in the worst cases allow contaminated water to get too close to your drinking line. The good news is that backflow is predictable once you understand how an RO system is supposed to move water, and there are clear, practical ways to minimize the risk.

In this article, I will walk through what “backflow” really means in the context of a residential RO system, how internal and external backflow happen, how to recognize the early warning signs, and what design and maintenance choices keep your drinking water safe and your system running efficiently. The explanations draw on long-term field experience plus guidance from technical sources such as Fresh Water Systems, Water Service USA, Ecosoft, Viomi, and Working Pressure Magazine.

How A Home RO System Is Supposed To Move Water

Before we can talk about backflow, we need to be clear about the normal direction of flow in a typical under-sink RO system.

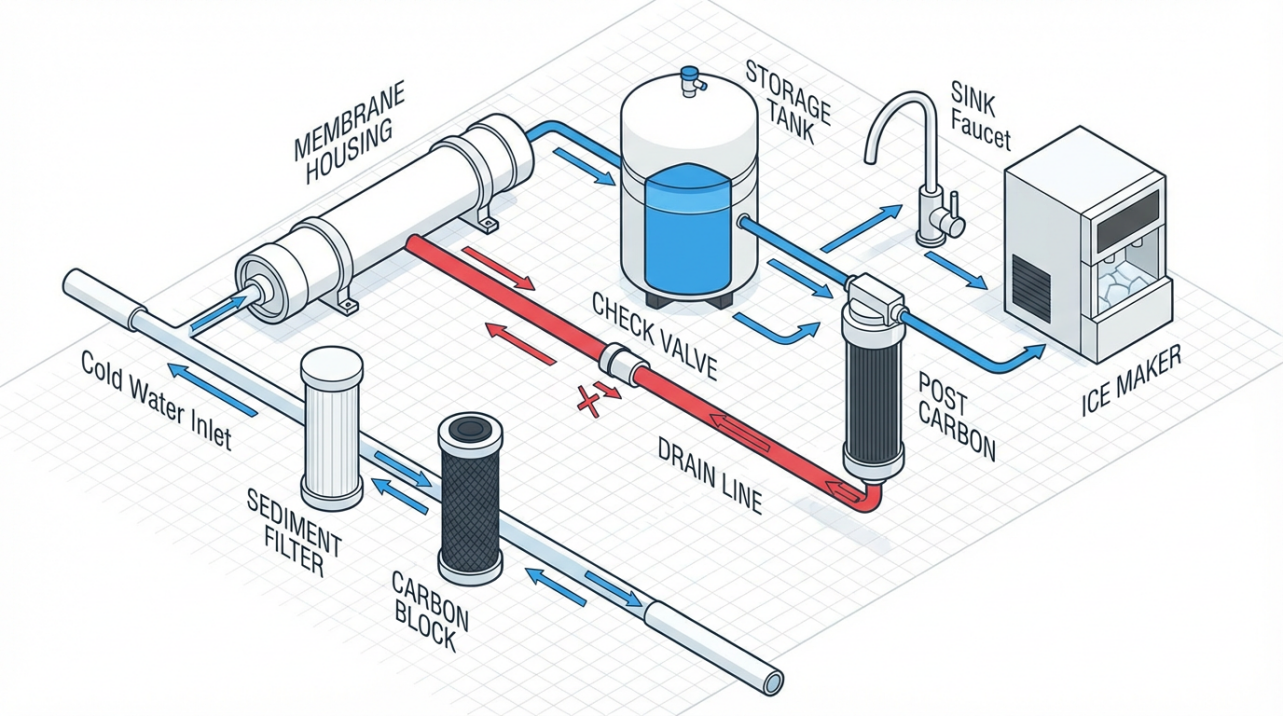

In a standard setup, cold tap water enters through a small feed line. It first passes through one or more prefilters, usually a sediment cartridge and a carbon cartridge. As described by Fresh Water Systems and other manufacturers, these stages catch dirt, sand, and chlorine so they do not plug or chemically attack the RO membrane.

From there, water reaches the RO membrane. The membrane sits in a sealed housing and uses household water pressure, ideally around 40–60 psi according to sources like ESP Water Products and Nelson Water, to push water through an ultra-thin barrier. Cleaned water that passes through the membrane is called permeate. Concentrated reject water, sometimes called brine or concentrate, exits on another port and heads toward the drain.

Most home RO systems do not send permeate straight to the faucet. Instead, they store it in a small steel tank with an internal rubber bladder and an air chamber. Several suppliers, including ESP Water Products, Fliers Quality Water, and Appliance Parts Pros, note that when this tank is empty it should have about 7–8 psi of air inside. As the membrane fills the tank with pure water, that trapped air compresses. Later, when you open the RO faucet, the compressed air pushes water out so you get a steady stream instead of a weak drip.

To coordinate all of this, the system relies on three small but critical flow-control parts, explained in detail by Fresh Water Systems, Viomi, and Water Service USA.

The flow restrictor sits on the drain line leaving the membrane. It throttles the waste stream just enough that pressure builds on the membrane, which is what makes RO work. The automatic shutoff (ASO) valve senses when the tank is full. It is designed to close when tank pressure reaches roughly two-thirds of the incoming line pressure so the system stops feeding the membrane and stops sending water to the drain. The check valve sits in the permeate line between the membrane outlet and the tank. Its single job is to allow water to flow from the membrane toward the tank, but never back from the pressurized tank toward the membrane and prefilters.

When all three are correctly sized and in good shape, water flows in one direction only: from the feed, through the filters and membrane, into the tank, and then to the faucet. Waste water flows steadily one way to the drain.

Backflow problems start when that one-way choreography breaks.

Key Direction-Control Components At A Glance

You do not have to memorize every part number under your sink, but it helps to know which parts exist mainly to keep water moving the right way.

Component |

Typical location |

Normal job |

Backflow risk if it fails |

Check valve |

Permeate line between membrane and tank tee |

Let tank fill, block reverse flow from tank |

Tank water can push back through membrane and filters |

ASO valve |

Between feed line and membrane |

Stop feed and drain flow when tank is “full enough” |

System may run constantly to drain |

Flow restrictor |

Drain line off membrane housing |

Maintain correct pressure across membrane |

Pressure imbalance, constant drain or poor output |

Air gap device |

RO faucet or drain adapter |

Prevent drain water traveling backward into RO system |

Drain backflow can reach RO waste line or faucet |

Those four components, combined with the tank’s air charge and overall water pressure, are at the heart of most RO backflow stories.

Two Different Meanings Of “Backflow” In RO Systems

When homeowners say their RO is “backflowing,” they are usually describing one of two very different situations. Understanding the distinction helps you decide how urgent the problem is and what to check first.

Internal backflow inside the RO unit

The first type happens entirely inside the RO system itself. This is what Viomi and Fresh Water Systems describe when they talk about the permeate-side check valve. When that check valve works, it holds the pressurized tank water on the tank side. When it fails or is missing, the compressed tank water can push backward through the membrane line.

Practically, this means water in the tank can run back toward the membrane and into the drain line instead of out to your faucet. Because the ASO valve depends on tank pressure to decide when to shut off, a leaky check valve lets that pressure bleed away. The ASO never sees a stable “two-thirds of feed pressure” signal and the system may continue sending water to the drain indefinitely.

From the outside, you might notice that the tank seems to fill slowly, your faucet pressure is poor, and the drain line gurgles or trickles constantly even when nobody is using water. Ecosoft and Water Service USA both tie this kind of continuous drain behavior to combinations of faulty check valves, ASO valves, incorrect tank pressure, and clogged membranes or filters.

Internal backflow wastes water and shortens membrane and pump life, but it does not automatically mean sewer water is touching your drinking line. It is mostly an efficiency and wear-and-tear problem. Left alone, however, continuous running can push a membrane into early failure, which then affects water quality.

External backflow from drains and supply lines

The second type is more serious from a health standpoint. This is where water from the building’s drain or supply can move in the wrong direction and come into contact with the RO waste line or even the potable plumbing.

Working Pressure Magazine highlights why this matters for modern point-of-use RO systems. During normal operation, the concentrate stream leaving the RO membrane carries the contaminants you wanted to remove, including things like lead or PFAS. If the drain connection is poorly designed or lacks an air gap, a clog in the household drain could push that contaminated water backward up the RO drain tubing.

Similarly, The First Principle’s article on dental practices describes inspections where RO units were installed without a double check valve on the cold feed and without any air gap on the drain. In that scenario, under unusual pressure conditions you could get water moving from a higher-risk zone back toward the main supply or toward the RO device in ways the designer never intended.

External backflow issues usually show up as water or even dirty water emerging at an RO faucet opening that is not the normal spout, as leaks around improvised drain saddles, or as unexplained quality problems where RO water does not match what your membrane and filters should be delivering.

In short, internal backflow is about the tank pushing the wrong way through the RO hardware.

External backflow is about the rest of your plumbing pushing the wrong way into the RO system or the potable line. Both matter, but the second deserves faster professional attention.

Why Internal Backflow Happens: Pressure And Valve Problems

Inside the RO unit, everything comes back to pressure balance and one-way valves. Several troubleshooting guides, including Fresh Water Systems, Water Service USA, and Ecosoft, describe a common pattern: a system that never really shuts off and keeps sending water to the drain long after the tank should be full.

Imagine a home with 60 psi city water, a common value in many residential neighborhoods mentioned in sources such as ESP Water Products. Fresh Water Systems explains that an ASO valve is designed to close when tank pressure reaches about two-thirds of supply pressure. Two-thirds of 60 psi is about 40 psi. When the tank’s air-side precharge is correctly set to around 7–8 psi empty, the membrane can build tank pressure up to that 40 psi point, the ASO closes, and flow stops.

Now consider what happens if the check valve between the membrane and tank begins to leak. As the membrane tries to fill the tank, some of that pressure bleeds back through the check valve toward the membrane and into the drain line. Tank pressure never stabilizes at 40 psi. The ASO valve never sees its shutoff condition. The RO runs for hours, sending a steady waste stream down the drain.

Viomi, which focuses specifically on check valves, notes that a constantly running drain line, a system that never seems to shut off, or a tank that fills very slowly despite new filters and correct tank air pressure are everyday symptoms of permeate-side check valve issues. They and Water Service USA both recommend a simple test: draw some water so the tank is partially full, then close the tank valve to simulate a full tank. If the system and drain continue running long after that, the check valve or ASO valve is likely at fault.

Low or incorrect tank air pressure makes everything worse. Fliers Quality Water, Ecosoft, and multiple troubleshooting guides agree that the tank should read about 7–8 psi with no water inside. If years of use have allowed that precharge to fall to, say, 2 psi, the tank behaves more like a waterlogged balloon. It stores some water but cannot build enough pressure to trigger the ASO properly. Appliance Parts Pros uses a simple rule-of-thumb check: a healthy, full tank feels heavy when you lift it and can deliver several glasses of water at decent pressure. A tank that always feels unusually light or delivers only about one cup at normal pressure before dropping to a trickle often has a ruptured bladder or air-side problem, both of which can complicate shutoff behavior and encourage internal backflow.

All of this means that inside the RO, backflow is almost never a single failure. It is usually a chain: a soft or leaking tank precharge, a tired check valve, and an ASO valve that has been forced to run full time for months instead of cycling on and off. That chain is exactly why regular pressure checks and inexpensive check valve replacements are considered “cheap insurance” in Viomi’s guidance and in many professional service practices.

Why External Backflow Happens: Air Gaps, Drains, And Code Issues

On the drain side, the story is less about tanks and more about plumbing physics and codes. When an RO system sends concentrate to a building drain, that drain is already carrying dishwasher discharges, sink waste, and whatever else flows through the trap. Under normal conditions, gravity carries everything toward the sewer, away from your RO.

The risk, as Working Pressure Magazine emphasizes, is that the RO concentrate line contains a more concentrated mix of the very contaminants you are trying to avoid drinking. If the household drain backs up because of a clog or poor design, you do not want that polluted mixture forcing its way back into your RO system or potable lines.

The classic solution is an air gap. The Perfect Water and Working Pressure Magazine both describe the air gap used in RO faucets and adapters as a deliberate break in the piping where water must drop across open air before it can reach the next pipe. Because water cannot jump across that gap under normal pressures, any backflow from the building drain spills safely into the sink instead of reaching the RO tubing.

In a typical air-gap RO faucet, there are three connections under the counter. One carries treated water up to the spout. One brings concentrate from the RO system up to the faucet. The third carries that waste from the faucet back down to the sink drain. Inside the faucet body, the waste stream discharges across an open gap and then falls into the outgoing drain tube. If the sink drain clogs, the backflow pushes up only as far as the gap window, where it visibly spills into the sink instead of entering the RO unit.

Homeowners often see this as a defect, because they notice water spilling from the side of the RO faucet when the dishwasher runs. In reality, as American Home Water and other troubleshooting resources point out, the faucet is doing exactly what it was designed to do. The real problem is usually a dirty or undersized drain line downstream, not the RO.

Air-gap faucets are not perfect. The Perfect Water notes that they are prone to gurgling noises, require a larger mounting hole, and are a poor match for undermount sinks if you do not use additional products to catch any overflow. They also depend entirely on your home having adequate drain capacity. When that capacity is marginal, they will send water out of their “window” more often, which can lead to countertop and floor damage.

Non–air-gap faucets use a simpler, quieter approach with just one line for treated water. When installers choose this style, they must handle backflow prevention another way, usually with a check valve or a code-listed drain adapter designed for that purpose. The Perfect Water mentions permeate pumps and garbage disposal drain adapters as common options, while Working Pressure Magazine stresses that generic drilled drain saddles are not allowed in many plumbing codes. UPC-listed adapters and faucets certified under standards like NSF/ANSI 58 or IAPMO PS 65 are preferred.

Upstream, code-compliant installations also protect the cold-water feed side. The First Principle’s dental case study shows how often RO units get connected without double check valves or adequate backflow protection on the supply line. For a homeowner, the practical takeaway is simple: whenever you add or replace an RO system, you want the installer to be able to explain, in plain language, how the installation prevents water from flowing backward from the RO into your home’s potable plumbing.

How To Tell If Your RO Is Experiencing Backflow

From a homeowner’s perspective, you rarely see backflow directly. What you see is behavior that does not match what a healthy RO system should do. The sooner you can connect those symptoms to a likely cause, the easier it is to prevent bigger problems.

Signs of internal backflow or continuous running

Internal backflow often shows up as a system that never truly rests. Fresh Water Systems and Ecosoft recommend listening and watching for a few specific signs.

First, pay attention to the drain line. After you draw several cups of water from the RO faucet, it is normal for the system to run and send a modest flow to the drain while the tank refills. That may take an hour or more, depending on your membrane size and inlet pressure, as ESP Water Products demonstrates with a simple flow-rate calculation. They suggest measuring how many ounces your RO produces in one minute with the tank disconnected and the faucet locked open, multiplying that by the number of minutes in a day, then converting to gallons. In their example, a system that produces 4 fl oz per minute yields about 45 gallons per day. That gives you a sense of how long a refill might reasonably take.

What is not normal is a steady gurgle or trickle to the drain many hours after the last use, day after day. When that happens, and especially when combined with low faucet pressure or a tank that never feels truly full, it suggests that the ASO valve is never getting its shutoff signal. As noted earlier, that often traces back to a leaking check valve, a low tank precharge, a damaged tank bladder, or a mis-sized or damaged flow restrictor.

Second, notice how your tank behaves when it is full. A healthy tank with the correct 7–8 psi precharge should deliver several glasses of strong flow before pressure drops. If you always get about one cup of strong flow followed by a thin trickle, sources including ESP Water Products, Fliers Quality Water, and Independent Water Service point toward a ruptured bladder. In that case, all of the water in the tank may be trapped in the air chamber, unable to maintain pressure, and the tank usually needs replacement. While a ruptured tank is not backflow itself, it contributes to the same chain of pressure problems that encourage internal reverse movement and continuous drain waste.

Signs of drain-related backflow and cross-contamination risk

External backflow problems are often more visible and more alarming. The Perfect Water and American Home Water both describe situations where air-gap faucets suddenly begin ejecting water from the small vent opening on the side of the faucet. This usually happens when the sink’s main drain line is partially blocked or when the RO waste tubing from the faucet to the drain saddle has sags or loops that trap debris. Rather than being a defect, this is the air gap doing its job and preventing that backed-up water from entering the RO system.

Working Pressure Magazine warns about another red flag: any RO drain connection that relies on a self-piercing saddle valve or an unlisted clamp drilled into a drain line. These makeshift fittings are both prone to leaks and poor alignment, and they lack the built-in backflow protection of listed adapters. If you see a thin bracket hugging the drainpipe with small screws and a hole drilled through the pipe wall, it is worth asking a plumber or water specialist whether a code-compliant adapter should replace it.

Discoloration or unusual taste in water from the RO faucet can also raise concern, but here the causes are broader. Multiple sources, including Axeon, Independent Water Service, and Ampac, note that most taste and odor problems trace back to expired filters, fouled membranes, or bacterial growth rather than to drain backflow. However, when odd taste coincides with a history of drain backups or questionable installation, it is a good reason to stop using the water until a professional evaluates both the treatment train and the plumbing connections.

Simple home checks vs professional help

There are a few safe, non-invasive checks most homeowners can do without tools.

You can listen to the drain with the cabinet door open. After a period of no use, a healthy system should be quiet. A constant hiss or trickle suggests a shutoff or valve problem.

You can carefully lift the tank to gauge how full it tends to be. A tank that is always light may indicate that the membrane is not producing, while an always-heavy tank that provides poor flow suggests a tank pressure or bladder problem.

You can observe when air-gap drips or spills happen. If they coincide with dishwasher cycles or heavy sink use, that points to a drain capacity issue rather than a defective RO system.

Beyond those simple checks, most valve tests described by Viomi, Fresh Water Systems, and Water Service USA involve closing specific valves, simulating a full tank, or watching drain flow while turning the feed on and off. If you are comfortable reading your system’s installation diagram and carefully following manufacturer instructions, those tests are informative. If not, or if you suspect external backflow toward your potable plumbing, the safest move is to shut off the RO feed valve and call a licensed plumber or qualified water specialist.

Preventing Backflow And Cross-Contamination Long Term

Preventing RO backflow is less about heroic fixes and more about stacking small design and maintenance decisions in your favor. The common thread across manufacturers and technical articles is that routine attention to valves, drains, and pressures keeps water moving the right way and keeps contaminants in their proper place—out of your glass.

Design and installation choices that matter

When you choose or reinstall an RO system, you make several one-time decisions that strongly influence backflow risk.

Air-gap versus non–air-gap faucet is one of them. As The Perfect Water explains, air-gap faucets provide built-in backflow protection on the drain side and help systems qualify under plumbing codes in areas where an air gap is mandatory. They are noisier and trickier around undermount sinks, but they are also a straightforward way to make sure that if the drain backs up, the resulting water goes into the sink, not into your RO device.

Non–air-gap faucets, in contrast, are quieter and require only a single treated-water connection. When you use them, you should ensure that the drain connection includes a certified backflow prevention method such as a drain adapter listed under standards cited by Working Pressure Magazine, rather than an improvised drilled saddle.

On the supply side, the same article advises against self-piercing saddle valves as a feed connection. A tee with a proper isolation valve, sized for the quarter‑inch or three‑eighth‑inch tubing most POU systems use, is more robust and easier to service. The First Principle’s dental practice example underlines that even in professional settings, installers sometimes omit required check valves on cold water feeds, so it is reasonable for a homeowner to ask which device protects their main line from RO-related backflow.

Material choice is another subtle but important factor. Working Pressure Magazine specifically cautions against using copper tubing on the permeate side because low-mineral RO water is more corrosive toward copper. Over time, that can lead to blue or green staining, elevated copper levels, and leaks, all of which complicate both water quality and leak diagnosis. Plastic tubing recommended by the RO manufacturer is the safer path.

Maintenance habits that keep flows one-way

Once your RO is properly installed, most of your backflow-prevention effort becomes routine care. Fortunately, the same habits that keep water tasting great also protect valves and pressure balances.

Filter and membrane change intervals are the first pillar. Across many sources, including Axeon, ESP Water Products, Fresh Water Systems, and Water Service USA, there is clear agreement that sediment and carbon prefilters should be replaced about every 6–12 months, postfilters roughly every year, and membranes every 2–3 years on hard water or somewhat longer on soft water. Those intervals protect the membrane from fouling and keep the flow restrictor, check valve, and ASO from fighting against unnecessary blockages.

Tank pressure checks are the second pillar. Fliers Quality Water, Appliance Parts Pros, and others point to 7–8 psi as the typical target when the tank is completely empty. Checking this every year or two with a simple tire gauge and bicycle pump, while the tank is drained and the feed shut off, is straightforward and has an outsized impact on how reliably the ASO can shut the system down.

Drain care is the third pillar. American Home Water emphasizes cleaning clogged RO drain lines and ensuring the drain saddle is correctly aligned on the pipe. Working Pressure Magazine adds that using code-listed drain adapters instead of drilled saddles reduces the risk of clogs and misalignment. Periodically inspecting under-sink drains for buildup, especially if you cook with oils or use garbage disposals heavily, reduces the chance that your air-gap faucet will ever need to prove its worth.

Sanitization rounds out the picture. Fresh Water Systems recommends sanitizing the RO housings and storage tank at least once a year, often at the same time as a scheduled filter change. This keeps bacterial growth from creating films that narrow passages, interfere with valve sealing surfaces, or compromise taste. When systems include atmospheric tanks or hot tanks, manufacturers usually specify separate sanitization procedures for those components as well.

A simple way to visualize how these habits work together is to imagine two checklists: one for one-time installation and one for regular care.

Area |

One-time choices that help |

Ongoing habit that helps |

Drain connection |

Use air-gap faucet or listed drain adapter |

Clean drain lines and check for kinks or sags |

Supply connection |

Use proper tee and isolation valve, add checks |

Inspect for leaks and retighten as needed |

Internal valves |

Ensure correct, quality ASO, check, restrictor |

Replace aged check valves on a preventative basis |

Tank |

Install correct size tank and set 7–8 psi |

Re-check and adjust precharge every year or two |

Filters/membrane |

Use manufacturer-approved cartridges |

Replace on schedule to avoid clogs and fouling |

When you get both columns mostly right, true backflow incidents become rare, and when they do occur they stay small and manageable.

FAQ: Common Questions About RO Backflow

Q: My RO faucet sometimes spits water from a small hole on the side. Is that dangerous backflow? When that small side opening belongs to an air-gap faucet, intermittent spitting is usually a sign that the sink drain is partially clogged or that the RO waste tubing from the faucet to the drain has developed a sag that traps debris. In that situation the faucet is actually protecting your RO system by dumping the backflow into the sink instead of letting it reach the RO tubing. Cleaning and straightening the downstream drain line, as suggested by American Home Water and others, typically resolves the behavior.

Q: Can an RO backflow issue contaminate my entire home’s plumbing? With a code-compliant installation that uses proper check valves and air gaps, the risk that an under-sink RO system will contaminate your whole home’s supply is very low. However, Working Pressure Magazine and The First Principle both document installations where required backflow protection was missing or incorrect. If you suspect your system was installed with improvised saddles or without checks and you also have recurring drain backups, it is wise to have a licensed plumber or qualified water treatment professional review the installation.

Q: Should I always choose an air-gap faucet for safety? Air-gap faucets provide robust drain-side backflow protection and are required by plumbing codes in some jurisdictions, especially when treating higher-risk water sources. They are excellent from a safety perspective but come with tradeoffs such as more noise and less flexibility with undermount sinks. Non–air-gap faucets, when paired with properly certified drain adapters and check valves, can also be safe and are often quieter. The best choice depends on your local code, the specifics of your kitchen layout, and your tolerance for noise versus visible safety features. Asking your installer to explain which standards your chosen faucet and drain adapter comply with is a good way to make an informed decision.

Closing Thoughts

RO backflow issues are rarely mysterious once you see your system as a set of pressure-driven one-way paths. When valves stay healthy, drains are properly protected with air gaps or listed adapters, and tank pressure is kept in the right range, water quietly does what it should: contaminants go to the drain, and clean water goes to your glass. Approach your under-sink RO the way you might approach your own hydration routine—with steady, thoughtful care instead of emergency fixes—and it will reward you with safer, better-tasting water and fewer surprises on the kitchen floor.

References

- https://www.watertechusa.com/reverse-osmosis-troubleshooting

- https://americanhomewater.com/reverse-osmosis-troubleshooting/

- https://www.thefirstprinciple.co.uk/single-post/reverse-osmosis-ro-backflow

- https://www.aosmith.com.ph/blog/disadvantages-reverse-osmosis-and-how-we-address-them

- https://www.culligan.com/blog/how-to-remineralize-reverse-osmosis-water

- https://www.ecosoft.com/post/most-common-problems-with-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/why-reverse-osmosis-water-flow-is-slow?srsltid=AfmBOooBeDfbiCb7FQOEuNo40tEG7nhuUr04wxIfH-b01VlmBJo5Nu51

- https://fliersqualitywater.com/5-reasons-that-your-reverse-osmosis-system-might-have-slow-water-flow-rates/

- https://independentwateryakima.com/what-are-the-most-common-problems-with-reverse-osmosis-water-systems/

- https://www.justanswer.com/appliance/snkt9-pressure-whirlpool-reverse-osmosis-unit.html

Share:

Understanding the Gurgling Sounds in Water Storage Tanks

Determining When Activated Carbon Filters Are Saturated: A Smart Hydration Guide