As a smart hydration specialist, I think about water in two layers every day. The first is purity: what techniques actually strip out particles, chemicals, and off‑tastes so the water you drink truly supports long‑term health. The second is separation: how we intelligently separate very pure water for drinking from “good‑enough” water for flushing, washing, and irrigation so we do not waste high‑quality water on low‑value tasks.

The good news is that the same science driving advanced municipal and industrial treatment is now reshaping home hydration. From dual‑media filters and membrane systems to dual water networks and recycled service water, we have a toolbox of proven, science‑backed techniques. In this guide, I will walk through those techniques, highlight their real‑world pros and cons, and show how to apply them in a practical, user‑friendly way at home.

Pure Water vs Clean Water: What Are We Actually Separating?

Before choosing technologies, it helps to define a few terms in plain language.

When water professionals say “pure water,” we usually mean water that has had nearly all particles and a large share of dissolved contaminants removed. Reverse osmosis (RO) systems, for example, can remove about 98% of total dissolved solids according to industry analyses summarized in H2O‑focused trade publications. This level of treatment is ideal for drinking, ice, coffee, tea, and any situation where you want consistent taste and minimized contaminant exposure.

“Clean water” is broader. It includes water that meets safety standards for its intended use, but not necessarily at RO‑level purity. Dual‑media filters that strain out sediment and much of the organic matter can produce very clean water for showers, laundry, and general washing. Municipal microfiltration plants, like the Manitowoc Public Utilities facility that treats about 13 million gallons of Lake Michigan water per day using membranes as a physical barrier to pathogens such as Cryptosporidium and Giardia, also produce reliably clean drinking water even if they do not strip every dissolved mineral.

“Clean‑water separation” means intentionally creating and managing different water qualities for different tasks. At city scale, dual water distribution systems send drinking‑quality water through one pipe network and non‑potable water through another network for irrigation, toilet flushing, and fire protection. At home, an under‑sink RO system that feeds your drinking tap while the rest of the house uses filtered but not fully purified water is a simple form of clean‑water separation.

With that framework, let us look at the techniques that actually make this possible.

Core Filtration Techniques That Create Pure Water

Sediment and Depth Filtration: The First Line of Defense

Nearly every effective water treatment train starts with mechanical filtration. In home systems, this is usually a sediment cartridge made from polypropylene depth media. In double water filter systems described by residential filtration specialists, stage one is a “PP cotton” filter that catches sand, rust, dirt, silt, and algae.

Depth filters work through a combination of physical straining, sedimentation, and interception, as described in classic water treatment handbooks used by plant operators. Instead of acting like a simple screen, the media has graded pore sizes so larger particles are caught in the outer layers and finer particles are trapped deeper inside. Many high‑quality sediment filters are rated to capture particles down to the size of about one‑thousandth of an inch. That is small enough to remove visible cloudiness from most tap water.

In practice, this stage protects everything downstream. In double filter systems, separating sediment removal from chemical adsorption keeps the second‑stage carbon block from clogging prematurely, preserves flow rate, and extends cartridge life. At whole‑house scale, sediment removal reduces wear on pumps and appliances and keeps water heaters from filling with insulating sludge.

The limitation is important: sediment filters do not remove dissolved solids or most dissolved chemicals. If you only install a sediment cartridge, your water might look clear but still taste strongly of chlorine or contain dissolved metals and salts. For pure water, you need more than mechanical filtration.

Dual‑Media Filtration: Higher Dirt Capacity and Cleaner Water

When a treatment plant needs to polish water after coagulation and settling, engineers often specify dual‑media or multi‑media filters rather than simple sand beds. Research briefed by water‑treatment manufacturers and engineering texts describes dual‑media filters with at least two layers: a top layer of coarse, low‑density anthracite and a lower layer of finer, denser sand. Some systems add a third high‑density layer such as garnet at the bottom.

Because the media layers differ in size and density, they naturally stratify after backwashing. Lighter anthracite stays on top, capturing larger particles, while denser sand and garnet below trap finer solids. This “depth filtration” spreads solids throughout the bed instead of blinding the surface, which allows higher filtration rates and longer filter runs compared with single‑media sand filters.

Technical summaries from dual‑media filter suppliers highlight that these systems are particularly effective for:

- Reducing turbidity and suspended solids.

- Removing much of the organic matter that can cause color and odor issues.

- Lowering concentrations of iron, manganese, arsenic, and some disinfection byproducts when paired with upstream coagulation.

In drinking water and groundwater treatment, dual‑media filters contribute to safer potable water and improved aesthetics. In wastewater polishing, they help meet discharge or reuse standards by stripping remaining solids before advanced processes such as reverse osmosis.

The upside is robust, high‑capacity cleaning with relatively low energy demand. The downside is that, like other granular filters, they only partially remove dissolved solids. They also require periodic backwashing with well‑controlled flow and sometimes air scour, plus occasional media inspection to avoid fouling and mudball formation.

Activated Carbon and Double‑Stage Filters: Taste, Odor, and Everyday Safety

If sediment filters are the muscle, activated carbon is the nose and tongue of your water system. Carbon is treated at high temperatures to create a matrix of microscopic pores, which adsorb many organic compounds and disinfectant residuals.

In a typical home double filter system described in residential guides, stage two is a carbon block cartridge. Water that has already passed through the sediment filter flows through this compressed carbon, which is far more effective than loose granular carbon because it prevents channeling and forces full contact. This stage targets chlorine, chloramines, many pesticides and herbicides, and numerous volatile organic compounds. It also dramatically improves taste and smell.

The health and comfort benefits are very tangible. When you strip chlorine out of shower water, people with sensitive skin often report less dryness and irritation. Removing the “pool” smell from tap water makes plain water more appealing, which naturally nudges families away from sugary drinks toward better hydration.

At whole‑house scale, reducing chlorine helps protect rubber seals and gaskets in fixtures and appliances, cutting leaks and maintenance costs. At under‑sink scale, a double‑stage system can transform the taste of drinking and cooking water at the tap.

The limitation, again, is dissolved solids. Standard sediment plus carbon systems do not meaningfully reduce total dissolved solids, minerals, salts, or many dissolved metals such as lead and arsenic. That is why the same home filtration guides explicitly recommend upgrading to RO when you face serious contamination, questionable well water, or a need for near‑total contaminant removal. Carbon also has a finite adsorption capacity and must be replaced, typically every six to twelve months in residential use, or whenever chlorine taste and odor return.

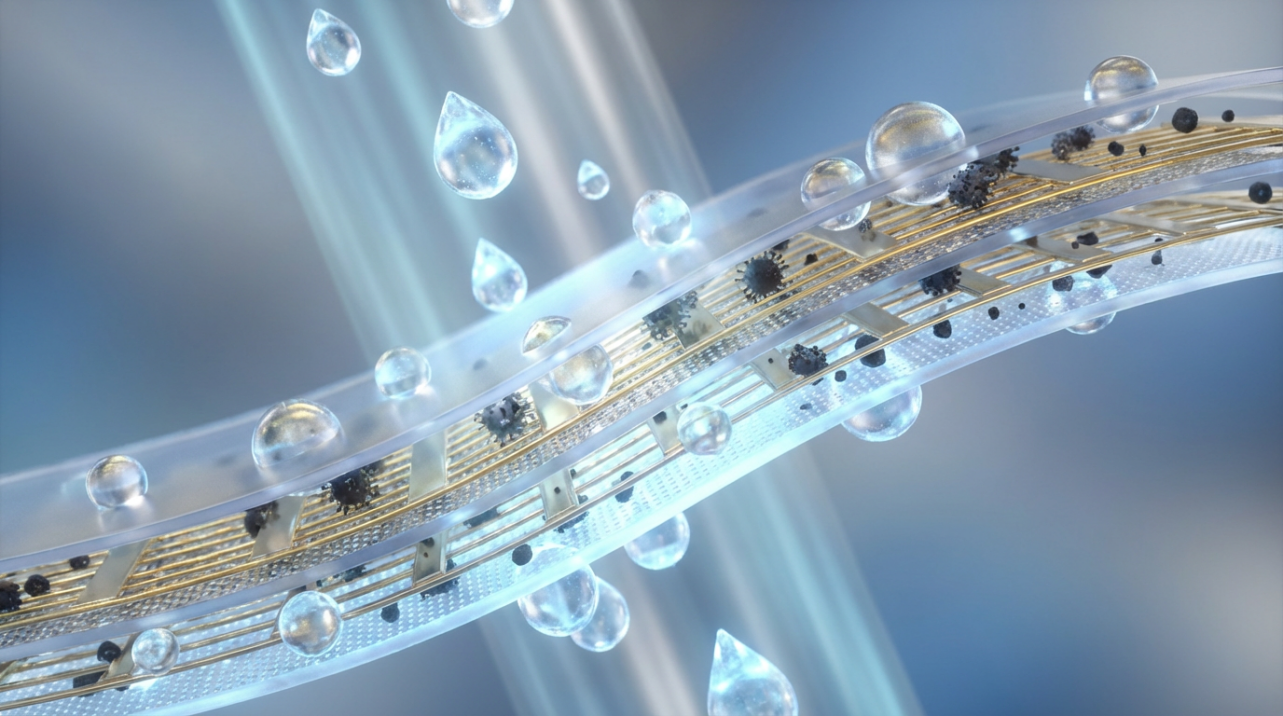

Membrane Filtration: Microfiltration, Ultrafiltration, Reverse Osmosis, and Nanofiltration

Membrane technology is where we move from “clean” toward truly “pure” water. Think of membranes as extremely fine sieves or barriers with pores so small they operate at the molecular level.

Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration: Physical Barriers to Pathogens

Microfiltration membranes, such as those used by Manitowoc Public Utilities on Lake Michigan water, use hollow plastic fibers with pores small enough to physically block protozoa like Cryptosporidium and Giardia and most bacteria. Each fiber is roughly the diameter of a human hair, but the flow passages inside are around one hundred times smaller than the hair’s thickness. As raw lake water is pushed through the walls of these fibers, particles and microbes stay on the outside and are periodically blasted off with air and water backwash.

Ultrafiltration goes even finer. Membrane bioreactor systems described by reuse specialists in Europe combine biological treatment with ultrafiltration modules that have pores small enough to retain essentially all particles, bacteria, and many viruses. A final ultraviolet disinfection step polishes the water. The result is hygienic “service water” suitable for irrigation, cooling, toilet flushing, and similar uses, even though it originates as domestic wastewater.

These processes are powerful for clean‑water separation, because they create a new category: non‑potable but very clean reclaimed water that can safely replace drinking water for many uses.

Reverse Osmosis: High‑Purity Water for Drinking and Specialty Uses

Reverse osmosis is the workhorse for high‑purity water at both industrial and home scales. In RO, water is pushed at elevated pressure against a semi‑permeable membrane. Pure water molecules squeeze through; most dissolved salts, metals, and larger organic molecules are rejected and carried away in a concentrated waste stream.

Independent market analyses on decentralized water treatment report that modern RO systems routinely remove about 98% of total dissolved solids when properly designed and maintained. They also note that newer residential RO units use water far more efficiently than older designs. Where legacy systems might waste roughly two‑thirds of the feed water as concentrate, newer systems can reduce the waste fraction to less than about one‑quarter.

In practical terms, that means:

- Much lower levels of dissolved contaminants in your drinking water.

- Softer water for coffee and tea, which can bring out more nuanced flavors.

- Stable water quality even when incoming tap water quality fluctuates.

However, the tradeoffs are real. RO lowers beneficial mineral content, which some people notice as a “flat” taste. The system produces a concentrate stream that must go to drain or, in advanced setups, into a reuse loop. Flow is slower, and under‑sink systems add complexity compared with a simple double filter.

Nanofiltration and Advanced Membrane Trains: Industrial‑Scale Separation

In industrial settings, companies such as DuPont Water Solutions have demonstrated membrane‑based strategies that go beyond simple RO. Nanofiltration (NF) membranes can selectively retain multivalent ions and larger organics while allowing some monovalent salts to pass. When combined with ultrafiltration, RO, and sometimes ion exchange, these membrane trains can:

- Pre‑treat challenging wastewater streams.

- Recover and reuse process water inside a plant.

- Concentrate brines to support minimal or zero liquid discharge goals.

- Recover valuable salts such as ammonium sulfate or sodium chloride as by‑products.

From a water‑wellness standpoint, the key point is that the same core science making industrial plants more sustainable also underpins the smaller RO and NF elements in advanced home systems.

System‑Level Clean‑Water Separation: Not All Uses Need Pure Water

Getting pure water to your glass is one thing. Managing water so you are not squandering drinking‑quality water on irrigation or toilet flushing is another. That is where system‑level strategies come in.

Dual Water Distribution: Two Networks, Two Water Qualities

A dual water distribution system uses two physically separate pipe networks in the same service area. Engineering summaries and case studies from coastal and island regions describe a typical configuration this way.

One network carries potable water that has gone through full treatment and disinfection. This water is intended for drinking, cooking, bathing, and other direct human contact. The second network carries non‑potable water drawn from seawater, reclaimed wastewater, or other sources that are treated to a level suitable for non‑consumptive uses.

Customers use the non‑potable water for toilet and urinal flushing, fire‑fighting, street cleaning, and irrigating ornamental plants and lawns. In some Caribbean installations, seawater is supplied this way. Pumping systems and elevated storage tanks deliver both streams, and valves, standpipes, and hydrants are designed for each network.

The benefits are substantial. Dual systems conserve scarce and expensive potable water by substituting cheaper non‑potable sources for tasks that do not require drinking quality. A research brief based on U.S. Environmental Protection Agency figures notes that landscape irrigation alone can account for roughly 30% of residential water use. Supplying that demand from a reclaimed or seawater network can dramatically relieve the load on potable supplies and reduce the need for new treatment capacity.

However, the risks and costs are real. Building and maintaining two separate pipe networks usually means roughly doubling the distribution infrastructure. Seawater is highly corrosive to many metals, which increases maintenance demands. Using untreated seawater or inadequately treated wastewater for irrigating leafy vegetables can create serious health risks and make produce unsafe. Above all, any cross‑connection between the potable and non‑potable networks could directly compromise drinking water quality.

For that reason, public health guidance from universities and regulators emphasizes strict separation, color‑coded piping (non‑potable lines are often purple), backflow prevention devices, clear labeling, accurate mapping of pipes, and staff training. When implemented carefully, dual distribution is a powerful macro‑level way to keep pure water for people while reserving lesser‑quality water for lesser‑value tasks.

Decentralized Treatment and Point‑of‑Use Separation

Traditional water systems rely on large central plants and long transmission mains. But as climate stress and urban growth make those systems harder to build and finance, decentralization is gaining ground.

Independent industry reporting on decentralized water treatment highlights several trends that matter for clean‑water separation:

Smaller, modular treatment units can treat water close to where it is used. Containerized plants such as the NIROBOX and NIROPLANT families promoted by Fluence are pre‑installed in standard shipping containers, can be deployed quickly (often in under four months from order to operation), and handle tasks from seawater desalination to brackish groundwater treatment. By producing high‑quality water at or near the point of use, they avoid long pipelines and associated losses.

In the home, decentralization shows up as point‑of‑use devices. Under‑sink RO systems and dual‑stage carbon filters let homeowners directly secure high‑quality drinking water at the tap instead of relying solely on utility‑delivered quality. Market analyses expect the point‑of‑use RO segment to triple in size by 2030, reflecting growing demand for local control over water quality and trust.

Industrial users are also decentralizing. Between the mid‑1980s and mid‑2010s, self‑supplied industrial water withdrawals in the United States fell by about 43%. Analysts attribute part of this reduction to modern technologies that enable on‑site water reuse and recycling. Service models such as Water‑as‑a‑Service let companies outsource the operation of advanced treatment trains while still dramatically reducing dependence on central supplies and discharges.

What ties all these examples together is strategic separation.

Instead of sending one uniform water quality everywhere, decentralized and point‑of‑use systems allow communities, businesses, and households to generate the specific purity they need where they need it.

Service‑Water Reuse: Recycling Treated Wastewater for Irrigation

Another powerful separation technique is recycling treated wastewater as “service water” for irrigation and non‑potable uses.

Technical briefs from European reuse specialists describe systems built around membrane bioreactors. Wastewater first goes through a compact biological treatment stage. The effluent then passes through ultrafiltration membranes with extremely fine pores, followed by UV disinfection. This combination retains particles, bacteria, and even many viruses, delivering hygienic service water suitable for irrigating fields, cooling buildings, or supplying toilets.

Compared with rainwater harvesting, effluent reuse is independent of roof area and rainfall variability, which means annual yields are more stable and storage tanks can be smaller. Compared with greywater‑only recycling, these systems treat all domestic wastewater, including kitchen and toilet flows. In many regions, that can amount to around 30 to 65 gallons per person per day of reusable water.

Because reclaimed water is generated daily and used directly, storage requirements stay modest. Case studies indicate that a volume on the order of a few hundred gallons can be stored on a footprint similar to a small walk‑in closet, which is a significant space advantage over large rainwater cisterns.

The financial and environmental benefits can be meaningful. In regions with high combined water and wastewater tariffs, reuse systems can amortize their cost in under about six years, all while reducing potable water demand, cutting wastewater discharges, and helping buildings reach higher sustainability certification levels under frameworks such as LEED or BREEAM.

The caveat is that effluent quality from the upstream sewage treatment plant is critical. If chemical oxygen demand and biochemical oxygen demand are too high, membrane fouling and maintenance needs increase substantially. That is why these systems rely on periodic membrane cleaning, backwashing, and careful monitoring.

Bringing It Home: Choosing the Right Technique for Your Hydration Goals

All of this technology can feel abstract until you match it to real‑world goals in your kitchen, bathroom, and yard. Here is a practical comparison of common techniques that appear across both professional and residential settings.

Technique |

What it does |

Best used for |

Key pros |

Key limitations |

Sediment plus carbon “double filter” (two‑stage) |

Stage one catches sand, rust, and silt; stage two carbon block removes chlorine, many organics, and odors |

Under‑sink drinking and cooking water; whole‑house protection for fixtures and appliances |

Strong taste and odor improvement; protects plumbing; no wastewater stream; cartridges typically affordable |

Does not significantly reduce dissolved solids or many heavy metals; relies on timely cartridge changes |

Dual‑media or multi‑media filter (anthracite, sand, sometimes garnet) |

Depth filtration that removes turbidity and suspended solids, plus some organic and metallic contaminants |

Whole‑house pretreatment; small community water systems; pre‑treatment before RO or UV |

High dirt‑holding capacity; long filter runs; supports higher flow rates; relatively low energy |

Only partial dissolved‑contaminant removal; needs periodic backwashing and media inspection |

Microfiltration or ultrafiltration membrane |

Physical barrier to pathogens and fine particles; can produce very clean non‑potable or potable water depending on design |

Municipal treatment plants; advanced home or building systems; reclaimed service water for irrigation and cooling |

Reliable pathogen removal; compact footprint; automatable with backwash cycles |

Does not fully remove dissolved salts; membrane fouling requires monitoring and cleaning |

Under‑sink RO system (often with pre‑filters) |

Removes most dissolved salts, metals, and many organics for high‑purity drinking water |

Dedicated drinking, ice, and cooking tap in homes or small food businesses |

Very high contaminant reduction; consistent taste and purity even with variable tap quality |

Produces a concentrate stream to drain; slower flow; more complex installation; reduces mineral content |

Small‑scale reuse system with membrane bioreactor and UV |

Converts treated wastewater to hygienic service water |

Irrigation, toilet flushing, cooling, and process water in buildings or farms with their own treatment plants |

Major reduction in potable water demand; daily, weather‑independent supply; potential for short payback in high‑tariff regions |

Requires existing or new small sewage treatment plant; design and permitting are more complex than simple filtration |

For most households, the practical path to pure water and smart clean‑water separation looks like this.

Use a good sediment plus carbon system at the point of entry or under the sink to handle the bulk of taste, odor, and sediment issues. This alone can transform how your water feels in the shower and tastes in a glass. If you know or suspect that your water contains serious dissolved contaminants such as high nitrate, arsenic, or lead, or you want the highest level of precaution for infants and immunocompromised family members, add an under‑sink RO unit to feed your drinking and cooking tap.

At the same time, pay attention to how you use water. Even if you do not have access to a dual distribution system, you can emulate its logic by using high‑purity water only where it matters most. There is usually no reason to feed RO water to toilets, hose bibs, or washing machines. Keeping those on filtered but not fully purified lines preserves cartridge life and minimizes waste.

Finally, if you own a small farm, greenhouse, or building with an on‑site wastewater system, it is worth exploring whether compact reuse systems could supply irrigation or cooling water. Case studies show that when designed correctly, these systems can reduce both water bills and wastewater fees while cutting the environmental footprint of your operation.

Practical Maintenance and Monitoring: Keeping Separation Smart, Not Set‑and‑Forget

Even the best filtration and separation design can underperform if maintenance is neglected. The most reliable operators, from municipal plants to home enthusiasts, treat filters and membranes as monitored assets, not hidden plumbing.

In residential double filter systems, stage one sediment cartridges typically need replacement every three to six months. Clear housings make this easy to judge: if the filter has turned dark orange or brown or if you notice a drop in water pressure at the treated tap, it is time to replace. Stage two carbon blocks usually last six to twelve months, depending on how much chlorine and organic load they see. When chlorine taste or odor returns, the carbon’s adsorption capacity is essentially exhausted.

For RO systems, pre‑filters must be changed according to manufacturer guidance to protect the membrane from clogging. The RO membrane itself can last several years if the pre‑treatment is robust and the system is flushed correctly. Many high‑quality units now include built‑in indicators or recommend simple total dissolved solids meters at the faucet so you can confirm that rejection performance remains high.

In large dual‑media filters, operators monitor two main indicators: effluent turbidity and head loss across the bed. When turbidity rises above a set threshold or head loss grows beyond the design limit, the filter is backwashed. Water treatment manuals emphasize initiating backwash based on these performance signals rather than just on a timer, since influent water quality can vary significantly.

Modern control technologies make this easier. Wastewater efficiency experts describe how programmable logic controllers and SCADA systems automatically adjust chemical dosing, pump speeds, and aeration based on sensor feedback. In one phosphorus removal case, switching from manual to automated, feedback‑driven dosing cut chemical use by about 15% while actually improving effluent quality. At scale, similar automation can help a plant maintain stable separation boundaries between potable, non‑potable, and waste streams without constant manual intervention.

On the distribution side, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes that national studies have found an average of about 14% of treated drinking water can be lost to leaks, with some systems losing far more. Smart metering and leak detection help utilities “account for every drop,” making sure that pure water actually reaches taps instead of disappearing underground. For households, late‑night meter checks and attention to unexplained usage spikes can serve as a simple analog.

The pattern is the same everywhere: design for separation, then monitor and maintain the barriers that keep pure water pure and non‑potable water in its lane.

Short FAQ: Everyday Questions About Pure Water and Separation

Do I always need reverse osmosis for healthy drinking water?

Not necessarily. If your water is already well treated and you mainly dislike the chlorine taste or occasional sediment, a high‑quality double filter system with sediment and carbon stages can be sufficient for many families. However, residential filtration guides and industrial sources agree that standard carbon systems do not reliably remove dissolved metals, salts, or many other dissolved contaminants. If you have known contamination issues, are on a questionable private well, or simply want the extra margin of safety and consistency, an under‑sink RO unit is the more appropriate choice for your main drinking tap.

Does RO “waste” too much water to be responsible?

Older residential RO systems were indeed quite wasteful, sometimes sending roughly two‑thirds of the feed water down the drain. Newer generations highlighted in decentralized water treatment analyses have significantly improved, with well‑designed units rejecting less than about one‑quarter of the feed as concentrate. If you are in a very water‑stressed region, you can also look for RO systems that route concentrate to non‑critical uses, such as pre‑rinse water for dishes or outdoor cleaning, instead of directly to the sewer.

Are dual water systems safe for families?

Dual water systems can be very safe when they are properly designed, installed, and managed under strict public health codes. Technical guidance from universities and utilities emphasizes the importance of completely separate pipe networks, color‑coded non‑potable pipes, backflow prevention, accurate maps, and regular inspections. The non‑potable water in these systems is meant for uses like flushing and irrigation, not drinking, and the greatest risk comes from accidental cross‑connections or misuse. When those are prevented by design and oversight, dual systems are a proven way to reserve high‑purity water for taps while saving large volumes of potable water at the community level.

Pure water and smart clean‑water separation are not just buzzwords; they are practical strategies that combine science, engineering, and everyday habits. By pairing the right filtration techniques with thoughtful separation of high‑purity and general‑use water, you can support your health, protect your home, and do your part to keep local water resources resilient for the long term.

References

- https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=200045LA.TXT

- https://actat.wvu.edu/files/d/bc936c72-9339-47b2-96b4-74c7aa0f6f0e/dual-water-systems.pdf

- https://www.mpu.org/services/water/water-facilities/

- https://blog.burnsmcd.com/6-strategies-for-improving-power-plant-water-treatment

- http://www.thewatertreatmentplants.com/dual-water-distribution.html

- https://www.aquaphoenixsci.com/enhancing-the-efficiency-of-your-wastewater-treatment-plant/

- https://www.fluencecorp.com/decentralized-water-treatment/

- https://h2oglobalnews.com/decentralized-water-treatment-the-solution-for-universal-safe-drinking-water/

- https://wtp-operators.thewaternetwork.com/article-FfV/5-ways-to-improve-water-treatment-plant-efficiency-DzLo5z7rh6WkGdubXe98SA

- https://www.wateronline.com/doc/combining-decentralized-and-centralized-wastewater-treatment-strategies-to-solve-community-challenges-0001

Share:

Why 304 Stainless Steel Faucets Cost More Than Copper Faucets

Carbon Fiber Filters vs. Traditional Activated Carbon: Which Is Better For Your Home Water?