If you rely on a smart water filtration or home hydration system, a small electromagnetic valve often decides whether your family gets clean, great‑tasting water on demand or a slow trickle, a constant dribble, or no flow at all. When that valve sticks, every part of the system—from filters to storage tanks and dispensers—can go out of tune.

As a smart hydration specialist, I see the same pattern again and again: people notice “weird” behavior at the faucet or dispenser, but they are not sure whether to blame the filters, the pump, or the little valve hidden inside the manifold. The good news is that you can usually tell whether an electromagnetic valve is stuck using a structured, science‑based checklist, without jumping straight to expensive part swaps.

This guide walks you through how electromagnetic (solenoid) valves work in water systems, the specific symptoms of a stuck valve, and practical tests you can do to distinguish a truly stuck valve from issues like bad wiring, incorrect pressure, or contamination.

What an Electromagnetic (Solenoid) Valve Does in a Hydration System

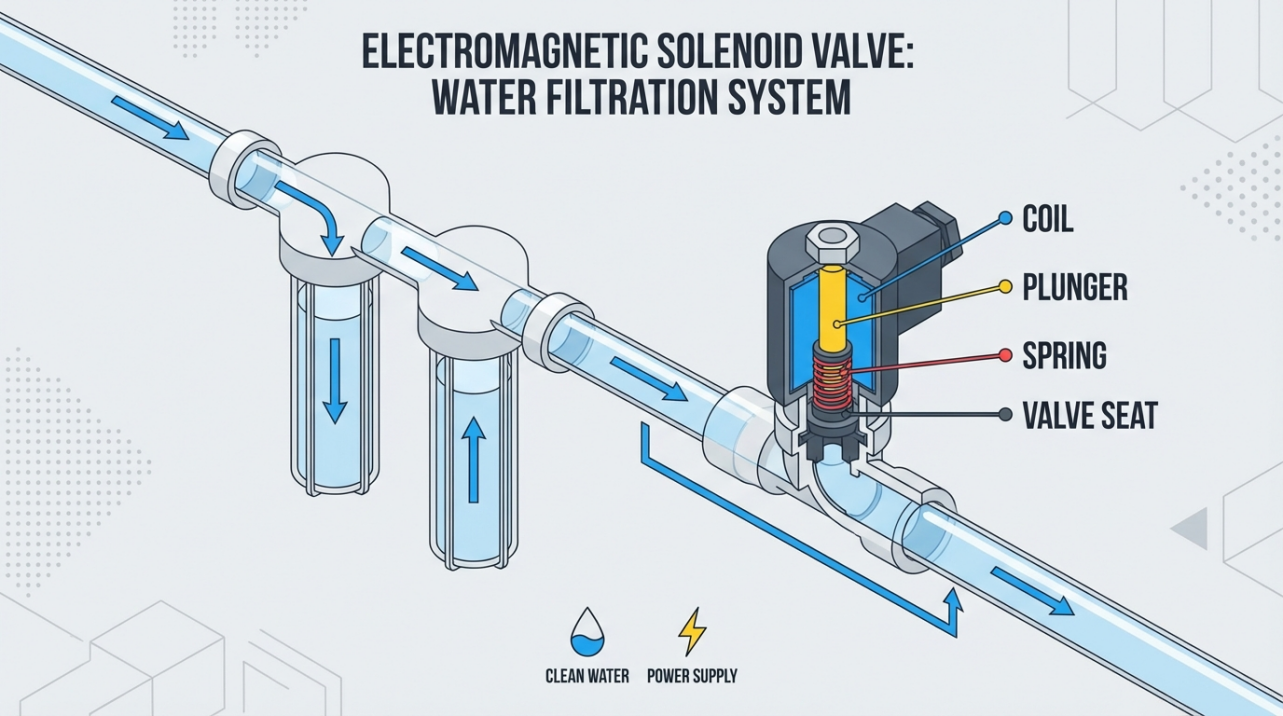

An electromagnetic valve, often called a solenoid valve, is an electromechanical switch for liquids. Technical references from U.S. Solid and BL Pneumatic describe the same basic anatomy: a coil of wire (the solenoid), a movable metal plunger or core, a spring, and a valve body with an orifice or diaphragm. When the coil is energized, it creates a magnetic field that pulls the plunger, opening or closing the flow path. When power is removed, the spring pushes the plunger back to its resting position.

Most hydration and filtration systems use one of these two behaviors:

- A normally closed valve, where the default state without power is closed. The system must energize the coil to allow water to flow. This is common where you want water to stop automatically during a power loss.

- A normally open valve, where the default state without power is open. Energizing the coil closes the valve. This is used less often in domestic drinking water systems but appears in some special designs.

Engineering guides from Tameson and Sprayervalves also distinguish between direct‑acting valves, where the coil directly moves the plunger against the full line pressure, and pilot‑operated valves, which use system pressure to help move a diaphragm or piston so a smaller coil can handle higher flows and pressures. In small filtration and dispensing systems you are more likely to see direct‑acting or semi‑direct valves, while larger building‑scale water systems may use pilot‑operated designs to handle higher pressures.

Some smart water systems use electric ball valves instead of traditional solenoid valves. ElectricSolenoidValves.com explains that these use a motor to rotate a drilled ball rather than pulling a plunger, but from your perspective as an owner the symptom checklist is very similar: when the actuator runs but the ball does not rotate fully, or the ball gets stuck mid‑stroke, you see partial or no flow.

Once you understand that the valve is simply a remotely controlled on/off gate, it becomes easier to reason about what “stuck” actually looks like in your home.

How Electromagnetic Valves Get Stuck

When people say a valve is stuck, they usually mean the valve no longer moves to the commanded position. Based on troubleshooting guidance from GES Repair, Tameson, Sprayervalves, MAC‑SMC, and Direct Material, there are three practical patterns: stuck open, stuck closed, and partially stuck or sluggish.

To make this concrete in a hydration context, imagine a small solenoid controlling the feed into a filter manifold or an electric ball valve shutting off a branch line.

Valve state |

What you typically observe at home |

What technical sources identify as common underlying issues |

Stuck open |

Constant flow when there should be none, zone or appliance never shuts off, system pressure drops and never recovers properly |

Loss of power that left valve frozen open, debris preventing closure, damaged seat or stem, burned coil that cannot move plunger back (GES Repair, Tameson, Sprayervalves, MAC‑SMC) |

Stuck closed |

No flow even though the controller calls for water, system tries to run but you get air or a trickle |

No power at coil, incorrect voltage, failed coil, plunger jammed by rust or particles, pressure differential outside valve’s operating range (Tameson, U.S. Solid, Sprayervalves, ElectricSolenoidValves.com) |

Partially stuck or sluggish |

Slow start, pulsing, noisy operation, partial flow, valves that take too long to open or close |

Debris on seat or diaphragm, bent armature tube, corrosion, excessive friction, incorrect pressure profile causing incomplete actuation (Tameson, Lee Company, BLPneumatic, Electric Ball Valve guidance) |

Stuck Open: Continuous Flow and Leaks

GES Repair and Maxim Systems both describe valves stuck open as a common failure mode. In practice, with a water filtration system this might look like a filter drain that never stops dripping, a storage tank that keeps filling and venting, or a dispenser that continues to run after you release the button.

From a technical standpoint, there are several ways to end up with a stuck‑open valve:

Power interruptions or controller errors can leave a valve frozen in its last energized position. GES Repair notes that if power is lost while a valve is open, the system may restore power in a way that fails to reset the coil, leaving the valve mechanically in the open state.

Coil burnout from overvoltage or wrong frequency can also freeze a valve. Tameson and ElectricSolenoidValves.com both warn that excessive voltage or mismatched AC frequency overheats coils, often causing permanent damage that prevents the plunger from returning properly.

Mechanical debris can physically stop the plunger or diaphragm from sealing. GES Repair and U.S. Solid both emphasize that foreign material lodged on the seat is one of the first things a technician should look for when a valve refuses to close.

A simple real‑world example is a whole‑home filter bypass solenoid that is supposed to open only during backwash. If it sticks open, you might notice that filtered and unfiltered water are mixing, or that the system never builds normal pressure. Even if you cannot see the valve, the combination of constant motion, pressure loss, and controller alarms points straight at the valve position.

Stuck Closed: No Flow When You Need It

A stuck‑closed valve looks very different. There is no water when there should be, even though upstream pressure is normal. Tameson and U.S. Solid both describe this as the classic “valve does not open” symptom.

Common root causes include:

Loss of power or incorrect wiring. Multiple sources, including Tameson, U.S. Solid, and Electric Ball Valve troubleshooting guides, agree that the first check is always electrical. If a normally closed valve never sees the proper coil voltage, it will behave exactly like a mechanically jammed valve.

Coil failure. Burned or open coils, described by MAC‑SMC and BLPneumatic, mean there is no magnetic field to move the plunger, even if the controller is trying.

Differential pressure outside the design window. Tameson and ElectricSolenoidValves.com highlight this especially for pilot‑operated or assisted‑lift valves. If the pressure drop across the valve is too high, the valve may not open; if it is too low, some designs cannot generate enough force to move the diaphragm. In a home setting this can show up after plumbing changes or pressure‑reducing valve adjustments.

Mechanical binding or corrosion. Rust, deformation of the armature tube, or mineral deposits can all clamp the plunger in place. Tameson and Sprayervalves both list corrosion and contamination as frequent culprits.

As a simple example, imagine a point‑of‑use filter under your sink that normally fills a 1 gallon pitcher in about 2 minutes. One day the flow drops to almost nothing, but your other cold‑water taps are fine. If the controller shows the system is calling for flow, the inlet shutoff is open, and filters are not overdue for replacement, a stuck‑closed solenoid at the manifold becomes a prime suspect.

Partially Stuck or Sluggish: The Hardest to Spot

The most subtle failures are those where the valve technically moves, but not fully or not at the right speed. BLPneumatic describes inconsistent performance, slow or hesitant actuation, and unusual noises as early warning signs. Tameson adds that valves may open only partially when differential pressure is marginal or when the armature tube is bent or corroded.

In a hydration context, this might look like:

Flow that starts weak, surges, then stabilizes.

A filter tank that takes three or four times longer than usual to fill.

Buzzing, chattering, or hammering noises from a cabinet or ceiling space when a zone opens.

ElectricSolenoidValves.com explains that poor pressure conditions, contamination under the diaphragm, or incorrectly sized valves can all produce this kind of behavior. The Lee Company emphasizes contamination as a major failure mode, where tiny particles jam internal components or erode sealing surfaces, causing erratic motion and leakage.

A quick mental calculation is helpful here. If your under‑sink system normally fills its storage tank in about 10 minutes and is now taking closer to 30 minutes under the same household usage, and filter age or inlet pressure have not changed, that three‑times increase is a clue that the valve may only be partially opening.

First Question: Is It the Valve or the Power?

Before you assume the valve is mechanically stuck, you need to rule out electrical problems. Several independent sources—including Tameson, U.S. Solid, and Electric Ball Valve troubleshooting guides—stress that initial diagnostics should confirm power supply and wiring.

In everyday terms, if the electromagnet never sees the right voltage, it will behave exactly like a stuck mechanical component.

Start by observing what the controller is doing. If you have a smart filtration system or building management interface, check whether it reports the valve as commanded open or closed. Schneider Electric’s building valve inspection guidance recommends trending actuator commands and positions versus temperatures or flows; the same idea applies at smaller scale. If the controller believes it has opened the valve but you still see no flow, the discrepancy is meaningful.

Next, listen for the valve’s normal sound. U.S. Solid notes that a healthy solenoid usually produces a faint click when energized. BLPneumatic adds that unusual noises such as loud buzzing, humming, or chattering can signal trouble. If you hear no click at all when the system calls for water, that suggests the coil is not energizing, there is a wiring problem, or the coil is already burned out.

If you are comfortable with basic electrical work and the valve is accessible, a low‑voltage multimeter check can add clarity. Tameson recommends verifying that the measured voltage at the coil matches the valve’s nameplate rating. If you see significantly less than the rated voltage when the controller calls for flow, the issue is upstream wiring or control, not a stuck plunger. If the voltage is correct but the valve never clicks or moves, a failed coil or mechanical jam becomes likely.

For safety, follow the same principles outlined in Maxim Systems and Tameson’s troubleshooting advice: shut off power before touching wiring, and treat any electrical work beyond simple measurement or visual inspection as a job for a qualified technician.

Second Question: What Does the Water Behavior Tell You?

Once basic power checks are done, your next diagnostic tool is the water behavior itself. Because valves, pumps, and filters all influence flow, you want to use patterns over time rather than a single observation.

MAC‑SMC points out that mechanical failure of an electromagnetic valve often shows up as abnormal pressure and flow: insufficient opening restricts flow and reduces equipment efficiency, while incomplete closing causes pressure loss. In filling systems, this shows up as inaccurate volumes; in fuel or steam systems, as reduced power or continuous leakage. The same patterns translate well to water filtration and hydration systems.

Look for changes rather than absolutes. For example:

If the system used to deliver about 64 fl oz into a countertop carafe in 1 minute and now delivers less than half that in the same time, without any other changes, a partially stuck or slow valve is one candidate.

If you can hear water flowing through a line or see the flow meter turning when every faucet and dispenser is off, and the controller is not calling for regeneration or flush cycles, that suggests a valve that is not sealing fully.

If a single zone or appliance behaves differently from the rest, that points toward the specific valve feeding it rather than global pressure or pump problems.

Guidance from Direct Material and BLPneumatic emphasizes leaks as a warning sign too. Leaks around the valve, especially at seams or where it joins the plumbing, can indicate worn seals, damaged diaphragms, or body corrosion. A visibly damp area around a valve in a cabinet or mechanical room should always be taken seriously from both equipment and hygiene perspectives.

It is also helpful to compare behavior during different operating modes. Many smart filtration systems perform automatic flushes or backwashes. If a valve seems to operate correctly during a flush but not during normal dispensing, that can hint at control logic or differential pressure issues rather than pure mechanical sticking.

Third Question: Is the Valve Fighting Contamination, Corrosion, or Wrong Pressure?

A valve that once worked and now sticks almost always changed because its environment changed. Across technical sources including Tameson, the Lee Company, PM International, MAC‑SMC, and Sprayervalves, three environmental factors show up repeatedly: contamination, corrosion, and mis‑matched pressure or temperature.

Contamination: Tiny Particles, Big Headaches

The Lee Company calls contamination or foreign object debris a major failure mode in solenoid valves. Particles carried by the water can:

Jam the plunger or diaphragm so it cannot move freely.

Erode seats and sealing surfaces, causing leaks.

Build up in orifices to the point where the valve cannot flow properly.

Tameson and U.S. Solid both note that dirt, rust, or debris inside the valve body are common reasons for valves that fail to open or close. Sprayervalves emphasizes that in spray and irrigation systems, rust, sediment, and missing internal parts are frequent causes of stuck or erratic valves.

In a filtration system, upstream sediment filters are supposed to catch most of this, but no filter is perfect and not every valve has its own fine screen. If you recently worked on plumbing upstream, disturbed scale inside pipes, or had a municipal main break, the risk of contamination temporarily spikes.

One practical example is a small piece of PTFE tape washed into the valve seat during a plumbing repair.

The system may work fine at first, then begin to leak through a “closed” valve once that fragment finds its way under the plunger.

Corrosion and Material Mismatch

PM International’s discussion of industrial valve failures identifies corrosion as a leading cause of valve degradation, especially when valve materials are not well matched to the fluid and environment. MAC‑SMC echoes this by noting that worn sealing surfaces from long‑term use or fluid impurities reduce sealing performance and cause leakage.

In high‑purity drinking water systems, you typically see corrosion‑resistant plastics or stainless steels, but there can still be problems at threaded joints, mixed‑metal connections, or older components not originally selected for today’s operating conditions. Over time, corrosion can roughen the bore where the plunger slides or damage the seat, increasing friction and making it more likely for the valve to stick in an intermediate position.

When signs of external corrosion, discoloration, or cracking are visible on the body or fittings, that is a strong indicator that internal surfaces may also be compromised. At that point, repair may be less reliable than replacement, especially in critical drinking water lines.

Pressure and Temperature Outside the Design Window

Tameson and ElectricSolenoidValves.com both emphasize that many solenoid valves have a specific operating pressure range. For pilot‑operated designs in particular, insufficient differential pressure can prevent the valve from opening or closing reliably. Conversely, exceeding the maximum working pressure can damage diaphragms or the body, leading to leaks, partial closing, or catastrophic failure.

Direct Material notes that incorrect valve sizing or operating outside pressure and temperature ratings is a common root cause of blockages and cracked valves. Sprayervalves adds that pressures up to roughly 300 psi and temperatures from around −40°F to 250°F are typical for agricultural valves, but each model has its own certified window.

In a home setting, if pressure‑reducing valves or pumps have been adjusted, or if you recently changed plumbing and pipe sizes feeding the valve, it is worth comparing the new conditions to the valve’s data plate or documentation. When a valve suddenly starts sticking after a pressure change, the problem may not be wear; the valve may simply be operating outside the conditions it was designed for.

Practical Checks to Confirm a Stuck Valve

Once you have a sense of whether the issue is electrical, hydraulic, or mechanical, there are several specific checks—drawn from Tameson, Maxim Systems, GES Repair, U.S. Solid, ElectricSolenoidValves.com, Sprayervalves, and BLPneumatic—that can help you confirm that the valve itself is stuck.

Always start by de‑energizing the system and closing any relevant shutoff valves, as emphasized in multiple repair guides. Working on pressurized or live electrical equipment is never worth the risk.

Begin with a visual inspection of the valve and wiring. Look for burn marks or cracks on the coil, loose or corroded terminals, and obvious leaks at joints or seams. U.S. Solid notes that a damaged coil usually needs replacement, and MAC‑SMC connects surface overheating and loose connections with internal electrical faults.

If the valve has a manual override or flow control stem, set it to the normal operating position. Maxim Systems’ irrigation guidance highlights that manual switches left in the wrong position can mimic a stuck valve by holding it open regardless of what the controller commands.

For accessible solenoid valves, gently removing the coil and plunger with power off allows a basic mechanical check. Maxim Systems and Tameson both describe inspecting the plunger to ensure it moves freely, cleaning it only with clean water and avoiding lubricants that can attract debris. If the plunger feels gritty, sticks, or shows signs of corrosion or scoring, mechanical sticking is highly probable.

Where safe, you can also isolate and test the valve in a controlled way. For example, close the upstream shutoff, relieve pressure, and then slowly reopen the shutoff while commanding the valve to open and close. If the valve remains in one position regardless of the command, or only moves partway, that is direct evidence of sticking.

In more sophisticated building or plant systems, Schneider Electric and CEPAI describe analyzing valve performance signatures or trending valve position, actuator current, and differential pressure over time to detect degradation before complete failure. While most home hydration systems will not expose that level of detail, the underlying idea still applies: consistent patterns in behavior carry more diagnostic weight than a single odd event.

When to Clean, When to Reset, and When to Replace

Knowing that a valve is stuck is only half the picture; you also need to decide what to do about it. Guidance from Tameson, Maxim Systems, GES Repair, ElectricSolenoidValves.com, Sprayervalves, and BLPneumatic points to three broad paths: simple reset, cleaning and minor repair, or full replacement.

If the root cause is clearly electrical and not the valve itself—such as a blown fuse at an irrigation controller, loose low‑voltage terminal, or misconfigured control signal—fixing the upstream issue and cycling power may restore normal operation. Maxim Systems specifically recommends checking controller fuses and wiring before assuming the valve has failed.

If your inspection reveals debris on the plunger, diaphragm, or seat, careful cleaning can often bring a lightly stuck valve back to life. Multiple sources recommend flushing dirt and sediment with clean water, re‑assembling with correct O‑rings, and ensuring all components are present. Tameson cautions that missing parts after disassembly are a recurring theme in persistent valve problems.

However, when you see burned coils, cracked housings, severe corrosion, or mechanically damaged stems and seats, replacement usually gives a more reliable outcome. ElectricSolenoidValves.com notes that simple, low‑cost valves are often cheaper to replace than to repair in depth, while complex or custom valves may justify repair kits. MAC‑SMC and BLPneumatic both stress that ongoing operation with a clearly degraded valve invites system‑wide issues, from inconsistent dosing to chain reactions on automated lines.

From a water wellness standpoint, any component that is visibly degraded, leaking, or no longer sealing properly in a drinking water path deserves a conservative approach. If there is any doubt about internal cleanliness or structural integrity, replacement with a correctly specified valve is the safer choice.

Protecting Your Water and Valves Over the Long Term

Although this article focuses on diagnosing a stuck valve, the broader goal is stable, healthy water at the tap. The same practices that keep valves from sticking also protect water quality and equipment.

PM International’s work on valve materials emphasizes that choosing corrosion‑resistant options for aggressive or high‑chloride environments can dramatically extend valve life and reduce unplanned failures. Relevent Solutions frames valve selection as a safety and reliability decision as much as a cost decision, stressing alignment with process media, pressure, temperature, and existing infrastructure.

Valve inspection guidance from Valveman highlights the value of periodic internal and external checks, even for valves that appear to be working, because fatigue, wear, and early leakage can often be spotted before they cause downtime. For critical components such as main shutoff valves or system bypasses, industrial practice even uses non‑destructive techniques like ultrasonic inspection, as described by EPRI for check valves.

In a home or light commercial hydration system, you probably will not bring in ultrasonic equipment, but you can still apply the same mindset. Keep an eye on how long tanks take to fill, whether flow patterns change seasonally, and whether any valves are running hotter or noisier than usual. Addressing those small signals early keeps both your valves and your water quality in a healthier range.

A stuck electromagnetic valve can masquerade as a bad filter, a tired pump, or “just low pressure,” but once you know what to look and listen for, it is much easier to isolate. Start by confirming that the coil is actually being powered, then let the water’s behavior guide you toward stuck open, stuck closed, or partially stuck states. When in doubt, especially on critical drinking water lines, favor clean, well‑specified replacement components over trying to nurse a severely degraded valve along. That way, your smart hydration system keeps doing what it was designed to do: deliver dependable, great‑tasting water every time you turn it on.

References

- https://maximsystems.net/blog/how-to-fix-a-stuck-solenoid-valve/

- https://www.directmaterial.com/4-common-problems-with-valves-you-need-to-be-aware-of

- https://www.epri.com/#/pages/product/3002003017/

- https://valveblog.jscepai.com/troubleshooting-common-electric-control-valve-problems

- https://www.mac-smc.com/?News/3566.html

- https://gesrepair.com/3-potential-solenoid-problems-troubleshooting-tips/

- https://www.justanswer.com/gmc/mh2rx-working-2008-yukon-hybrid-vvt-control.html

- https://www.sprayervalves.com/how-to-fix-a-stuck-solenoid-valve/?srsltid=ARcRdnpEUMrRryUNvjmaaonFvha6t9fHYUglTRt_57A1NuOM7saNUPAq

- https://tameson.com/pages/solenoid-valve-troubleshooting-the-most-common-failure-modes

- https://www.blpneumatic.com/news/signs-of-solenoid-valve-failure/

Share:

Emergency Repair Techniques for Broken Filter Clips in Appliances

Identifying Water Stains at Joints: Leakage or Condensation?