Why TDS Readings Matter For Modern Home Hydration

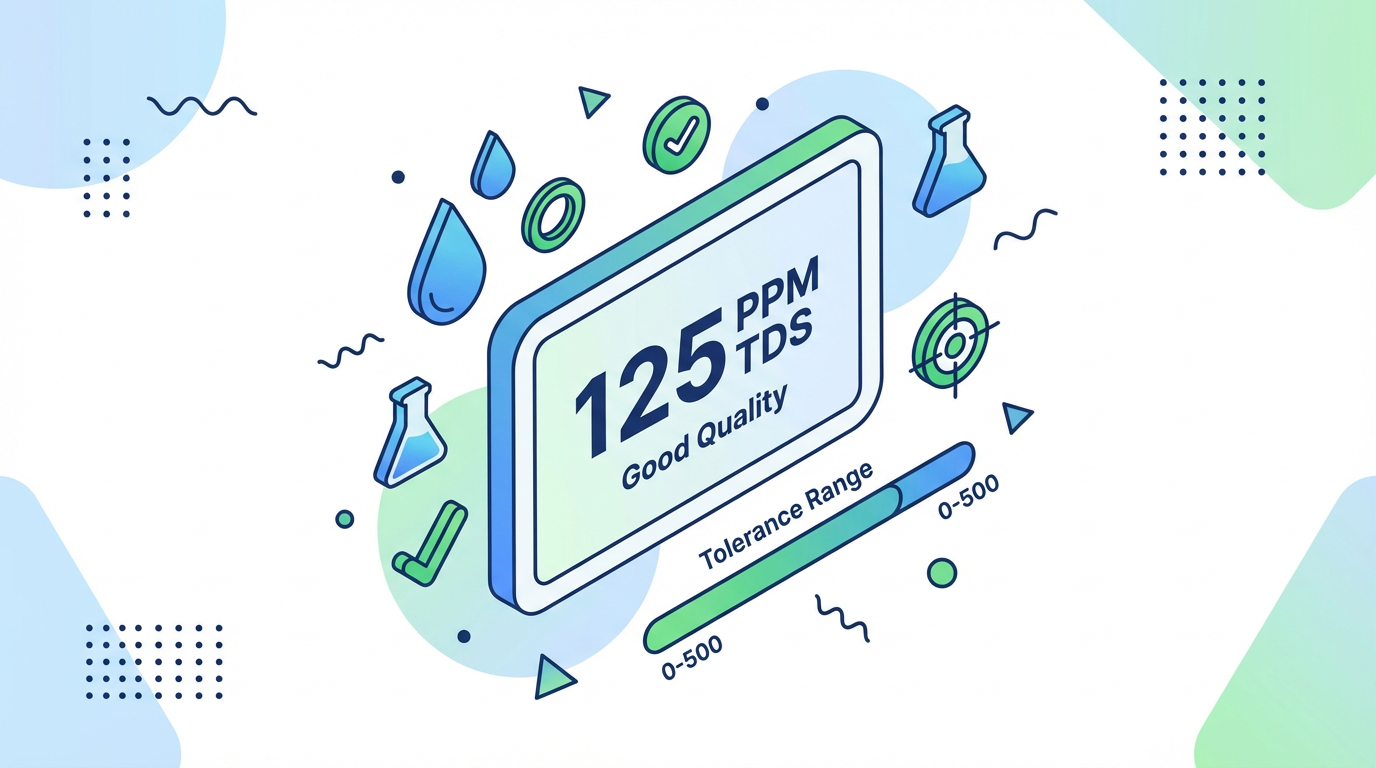

When I sit down with a family designing their first smart filtration and hydration setup, the conversation almost always lands on one number on the display: TDS in parts per million. That single reading on a smart faucet, RO dispenser, or handheld meter becomes the shorthand for “good water” or “bad water.” It is an incredibly useful number, but it is also just a measurement, and like any measurement it comes with error.

Total dissolved solids, or TDS, describe how much dissolved material is in your water. Multiple sources, including technical guides from HM Digital and background documents from the World Health Organization, define TDS as the combined presence of dissolved minerals, salts, metals, and small amounts of organic matter, usually expressed in ppm or mg/L. Smart TDS monitors infer this value from electrical conductivity and then apply a conversion factor.

As a Smart Hydration Specialist, what I care about most is not whether your monitor says 142 ppm or 146 ppm. I care whether that reading is accurate enough to tell us that your treated water is in a healthy range, your filters are still doing their job, and your home is protected from excessive scaling or contamination. That means we need a clear, science-backed sense of what “acceptable error tolerance” really looks like for a smart TDS monitor in a home hydration context.

What TDS Really Measures (And What It Does Not)

TDS is a broad, non-specific indicator. According to WHO guidance, library resources such as the Los Angeles Public Library’s water-quality materials, and several water-treatment manufacturers, TDS includes common minerals like calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium, along with anions such as bicarbonate, sulfate, chloride, and nitrate, plus trace metals and small amounts of organic matter. If it is dissolved and small enough to stay in solution, it contributes to TDS.

Because of this, a TDS monitor is excellent at answering questions like “Is my reverse osmosis system still stripping out most dissolved solids?” or “Has my well water suddenly become much more mineral-heavy than last year?” It is not good at answering “Is my water free of lead?” or “Are there pesticides present?” EPA drinking water regulations for organic chemicals and heavy metals are set at extremely low concentrations, often in parts per billion. A TDS meter does not resolve individual contaminants at that level; it simply sums the overall dissolved content.

Several sources, including HM Digital’s meter instructions and educational pieces from public libraries and manufacturers such as Frizzlife and Waterdrop, stress this limitation. The meter gives you a quick snapshot of total dissolved solids, not a full safety certificate. From a risk perspective, that also means that tiny errors in a TDS reading are far less important than many people imagine, because the number itself is an indirect indicator rather than a precise toxicology test.

Typical TDS Ranges And What They Mean For You

Different organizations and experts define slightly different “sweet spots” for drinking water TDS, but they converge on a few key ideas.

A WHO background document, as reflected in multiple summaries, classifies water with TDS below about 300 ppm as excellent in terms of taste, 300–600 ppm as good, 600–900 ppm as fair, 900–1200 ppm as poor, and above 1200 ppm as increasingly unacceptable to most consumers. The US Environmental Protection Agency and Canadian guidelines treat 500 ppm as a secondary (aesthetic and operational) upper guideline rather than a strict health limit, and many sources recommend staying below that value for drinking.

Some health- and taste-focused companies tighten that band further. Crystal Quest, OneGreenFilter, Frizzlife, and others describe an ideal drinking range around 50–150 ppm, with water between roughly 150–300 ppm still safe but more mineral-tasting. Zero or near-zero TDS water from aggressive reverse osmosis or deionization is generally described as safe but flat in taste and more likely to leach metals or flavors from plumbing and appliances.

A composite view based on these references looks like this:

TDS range (ppm) |

Typical description |

Common guidance for drinking |

0–50 |

Very low, “too pure” for everyday taste |

Often produced by RO or distillation; safe but flat and low in minerals; better for special uses than daily hydration |

50–150 |

Clean, crisp, mineral-balanced |

Frequently described as an ideal range for taste, health, and appliance performance |

150–300 |

Mineral-rich but generally pleasant |

Still widely considered good or acceptable; may have a more pronounced mineral or salty note |

300–500 |

Noticeably mineral or salty |

Within EPA’s secondary limit but more scale-forming and sometimes off-tasting; many experts recommend filtration |

500–1000 |

Above aesthetic guidelines |

Often labeled potentially unsafe for long-term use; may indicate problematic salts or metals; treatment strongly recommended |

>1000 |

Unacceptable for routine drinking |

WHO and EPA-aligned materials treat this as unfit or unsafe, especially long term |

When you look at this table, it becomes easier to see how meter error fits into the bigger picture.

For most households, the question is whether their treated water generally falls in the roughly 50–300 ppm band and stays well below 500 ppm. The exact number within that band matters less than staying in the right neighborhood and watching for meaningful changes over time.

How Smart TDS Monitors Work – And Why They Are Never Perfect

Smart TDS monitors do not “count particles” one by one. They measure conductivity and infer TDS. Dissolved ions such as sodium, calcium, and chloride carry electrical current, so the more ions in the water, the more conductive it is. The monitor measures that conductivity and uses a built-in conversion factor to estimate TDS in ppm.

Handheld meters and inline smart sensors use the same core idea. An HM Digital handheld meter, for example, is specified for a range up to about 9,990 ppm with a resolution of 1 ppm in the low range and an accuracy around ±2 percent of the reading. Automatic temperature compensation helps correct for the fact that conductivity changes with temperature, but this compensation works best in normal water temperatures rather than very hot samples.

Many modern reverse osmosis systems, such as those highlighted by Waterdrop, incorporate continuous TDS sensors in the base unit. They display or log TDS in real time so you can see, for instance, that inlet tap water sits around a few hundred ppm while product water is in the tens of ppm. That is tremendously helpful for filter maintenance and reassurance, but the underlying measurement is still a conductivity-based estimate.

Research from the US Geological Survey underscores how “estimated” TDS is in general. When they compared different TDS methods against a full ion-sum reference across thousands of surface-water samples, they found that standard TDS measurements had a median negative bias of roughly 19–24 percent compared with the comprehensive ion-based calculation. That is not a failure of the meters; it is a reminder that TDS is an operational measure defined by how you choose to measure it, not a fundamental constant of nature.

All of this means that obsessing over a one or two ppm difference between devices misses the point. The technique itself has an inherent level of approximation. What matters for a home hydration system is that your monitor is consistent, reasonably accurate, and stable enough to support good decisions about filters, remineralization, and maintenance.

Accuracy, Precision, Resolution, And Drift

Before we can define “acceptable error tolerance,” it helps to separate a few concepts.

Accuracy is how close a reading is to the true value. If your water is really 150 ppm and your monitor reads 150 ppm, you are accurate. If it reads 170 ppm, the error is 20 ppm.

Precision describes how repeatable the readings are. If you measure the same glass repeatedly and get 170, 171, and 170 ppm, you are precise but not accurate. If you get 140, 170, and 210, you are neither precise nor accurate.

Resolution is the smallest change the monitor can display. Many pocket meters show readings in steps of 1 ppm in lower ranges. That does not mean they are accurate to 1 ppm; it just means that is the smallest increment they show.

Drift is how accuracy changes over time. Electrodes age, sensors foul, and calibration shifts. The D-D TDS-3 handheld meter documentation, for instance, recommends calibrating at about 77°F using a known TDS standard solution (commonly 342 ppm sodium chloride). If the reading is off by more than about 2 percent from the standard value, the internal calibration screw should be adjusted until it is within that band again.

When a manufacturer lists accuracy “around ±2 percent of reading,” as HM Digital does for typical pocket TDS meters, they are defining the expected worst-case difference between the displayed reading and the true value after proper calibration and under normal conditions. That ±2 percent becomes the starting point for thinking about error tolerance.

How Big Is A ±2% Error In Real Life?

Because many household TDS meters cluster around ±2 percent of reading, it is helpful to put numbers on what that actually looks like.

Displayed TDS (ppm) |

Approximate ±2% range (ppm) |

Practical impact for drinking water |

50 |

49–51 |

Still firmly in the very low to “ultra-pure” category; taste and mineral concerns unchanged |

150 |

147–153 |

Squarely inside the widely recommended 50–150 ppm sweet spot; the difference is imperceptible in taste |

300 |

294–306 |

Right at the boundary between “good” and “fair” in many taste tables, but still below most aesthetic limits |

500 |

490–510 |

Straddles the EPA 500 ppm secondary guideline; either way, it is near the threshold where treatment is advisable |

1000 |

980–1020 |

Well above commonly recommended limits; even the low end of the range would still flag the water as unsuitable for regular drinking |

Notice what this means in practice.

If your filtered water reads 120 ppm, a ±2 percent error means the true value is roughly between 118 and 122 ppm. From a health and taste standpoint, every credible source would put that water in essentially the same category. Even at 300 ppm, the error band is only about ±6 ppm, which does not change the big-picture interpretation.

Where error matters more is when you are near a critical decision threshold. Around 500 ppm, a small error can make the number appear just inside or just outside the EPA’s secondary guideline. In that range, I treat a reading in the high 400s the same way I treat a reading in the low 500s: as a clear signal to investigate and likely treat the water, rather than arguing over ten ppm on the display.

For ultra-pure applications, such as reef aquariums targeting roughly 0–5 ppm or laboratory uses seeking 1 ppm or less, a ±2 percent meter on a very low value will display zero but may still be slightly off. That is where calibration and cross-checking become more important, and where specialized meters or multiple devices may be worth the investment.

When TDS Meter Error Really Matters

In daily hydration, TDS error is rarely the limiting factor. What matters most is staying in a broadly healthy range, maintaining good filtration, and monitoring for major changes.

Multiple sources, including Crystal Quest, OneGreenFilter, Frizzlife, and HTT, all converge on the idea that everyday drinking water is best somewhere around 50–300 ppm, with a practical upper ceiling around 500 ppm for city water and a lower ceiling for private wells or vulnerable populations. As long as your smart monitor keeps you obviously within that terrain, a small numerical error does not change the key decisions.

There are situations, however, where tighter control is more important. Crystal Quest notes that reef aquariums typically aim for 0–5 ppm TDS in make-up water, and that very low TDS water is also preferred for some baby formula preparation and specialty coffee. A forum post from the window-cleaning industry highlights another case: pure-water pole systems used for spot-free glass often demand water near 0 ppm, because even modest dissolved solids can leave visible spots on windows as the water dries. In those scenarios, a difference between 0 and 30 ppm can be the difference between success and failure, and users rightly become sensitive to potential meter error.

High-TDS situations at the other extreme also deserve attention. Articles from HTT, Quench, and public library resources emphasize that TDS above about 1000 ppm is generally unfit or unsafe for normal drinking, and that very high TDS can drive corrosion, scaling, and off-tastes. In regions with naturally mineral-rich or brackish water, or where agricultural or industrial activities add to the dissolved load, you may work around those high numbers with aggressive treatment such as reverse osmosis. In those cases, you want your monitor to be accurate enough to confirm that post-treatment water has been brought down into the recommended bands.

Sources Of Error In TDS Monitoring

From fieldwork and the manufacturers’ own documentation, the same sources of error come up again and again.

Temperature is one of the biggest. Conductivity changes with temperature, so TDS meters include automatic temperature compensation. Nonetheless, both HM Digital and the D-D TDS-3 instructions caution that measurements should be made in normal temperature samples and that very hot water can damage sensors or overwhelm compensation. Inline smart sensors in hot under-sink environments are not immune; if they see water that is much hotter than their design range, readings may drift.

Immersion and air bubbles matter too. The D-D TDS-3 guidance emphasizes immersing only to the marked level, tapping or stirring lightly to dislodge trapped bubbles, and allowing 10–30 seconds for the reading to stabilize. In practice, I have seen air bubbles cling to probe surfaces in RO storage tanks, causing artificially low readings until the water flows enough to sweep them away.

Contamination on the electrodes is another common culprit. Manufacturer guides recommend rinsing with clean or deionized water before and after use, never touching the metal sensors, and not storing meters wet. Persistent films from hard water, biofilm in tubing, or cleaning chemicals can all interfere with conductivity and skew readings. Inline smart sensors are exposed constantly, so periodic flushing and, if the design allows, gentle cleaning becomes part of keeping error under control.

Calibration and drift over time round out the picture. Pocket meters are often factory-calibrated at a standard solution such as 342 ppm sodium chloride. But heavy use, storage in hot environments, or large temperature swings can shift that calibration. Both HM Digital instructions and the D-D TDS-3 article recommend periodic recalibration or at least verification against a standard solution, particularly if you rely on the reading for important decisions.

Battery condition may seem trivial, but fading displays and low battery voltage can cause unstable or inconsistent readings. Manufacturers advise replacing batteries when the display fades to maintain accuracy.

Finally, there is the limitation of the method itself. The USGS paper shows that even carefully done TDS measurements can diverge by around 20 percent from ion-sum calculations depending on how you define and measure “total dissolved solids.” That is methodological error, not device error, but it puts the ±2 percent device accuracy into perspective: the instrument is usually much more precise than the underlying conceptual shortcut of using TDS as a proxy for water quality.

Setting A Practical Error Tolerance For Home Smart TDS Monitors

When I help homeowners specify or evaluate smart TDS monitoring, I focus on matching error tolerance to the use case rather than chasing laboratory-grade perfection.

For everyday drinking water from a municipal source, the goal is to stay in the broad, healthy band that multiple sources describe: roughly 50–300 ppm for optimal taste and mineral balance, comfortably below the 500 ppm aesthetic ceiling. A meter with accuracy around ±2 percent does that easily. If your smart monitor shows stable readings in that range and you confirm them occasionally with a handheld device or water-quality report, I consider the error tolerance more than acceptable.

For RO-based drinking systems producing very low TDS water that is then remineralized, the critical question is whether the RO stage is still stripping out most dissolved solids and whether the final remineralized water is within your preferred taste band. Reverse osmosis typically reduces TDS by more than 95 percent according to multiple manufacturer guides, and RO product water often falls in the 10–50 ppm range. Even with a few ppm of error, you can clearly distinguish between properly functioning RO output and a membrane that has begun to fail, where readings creep upward toward inlet values.

For sensitive specialty uses at home, such as reef tanks or pure-water window cleaning, I tighten expectations without necessarily demanding engineering-grade meters. In that context, I want to know whether the meter can reliably distinguish 0–5 ppm from 20–30 ppm, and I will often advise using a second meter or periodic lab testing when the cost of failure is high, because forum discussions from those industries highlight how a meter that silently reads 0 while delivering much higher TDS can cause real problems.

In all of these cases, the acceptable error tolerance is not a single magic number; it is a combination of the meter’s specifications, calibration practices, and how close you operate to important TDS thresholds.

Checking Whether Your Smart TDS Monitor Is “Close Enough”

Practically, you do not need complex statistics to decide if your TDS monitor is within an acceptable band. You need a couple of reference points and a bit of common sense.

One straightforward method is to use a commercial TDS calibration solution labeled with a known value, such as 342 ppm sodium chloride. The D-D TDS-3 instructions recommend calibrating at around 77°F by immersing the meter in the solution, waiting for the reading to stabilize, and then adjusting the internal calibration control until the displayed reading matches the standard. After adjustment, they advise verifying that repeat measurements are within about 2 percent of the standard value. If your meter cannot be brought within that range, or if readings wander significantly, it may be damaged or defective.

Another method is comparative. If your home is served by a stable municipal source and your utility provides recent TDS or conductivity data, you can compare your monitor’s reading on cold tap water to that reported value. You do not expect a perfect match, especially if the report is a system-wide average, but you do expect the numbers to be in the same general range. If your monitor reads 50 ppm on tap water where reports consistently show around 400 ppm, the odds are high that something is wrong with the device or its installation.

Cross-checking devices is also sensible where water quality matters. The window-cleaner forum post mentioned earlier captures the discomfort of seeing obviously dirty water while the meter confidently displays 0 ppm. In those cases I encourage professionals and serious hobbyists to keep a second, independent meter or to use test strips as a rough sanity check. If one device consistently disagrees with both a calibration solution and a second meter, it has failed the real-world error tolerance test.

For smart inline monitors built into RO systems, you may not have access to a calibration screw, but you can still verify them periodically with a handheld meter on the same water samples. The aim is not to force them to match perfectly but to confirm that they are broadly aligned and that trends over time are real and not artifacts of drift.

Pros And Cons Of Tightening Your Error Tolerance

People sometimes assume that “more accurate” is always better, but in home hydration there are trade-offs.

On the positive side, insisting on tighter error tolerance pushes you toward better-built meters, regular calibration, and thoughtful installation. That can be especially valuable in high-stakes uses such as infant formula preparation, home dialysis support under medical guidance, or reef aquariums where tiny differences in water quality matter.

The downside is cost, complexity, and misplaced confidence. Higher-precision meters tend to be more expensive and more sensitive to calibration technique. More importantly, ultra-precise TDS readings can give a false sense of security. A perfectly accurate 120 ppm TDS reading tells you the total dissolved solids with great confidence, but it does not reveal whether a few parts per billion of a regulated pesticide or a heavy metal have crept into your supply. EPA contaminant tables show that health-based limits for many organic chemicals and metals are set at tiny values compared with overall TDS, which a TDS monitor cannot resolve.

In my experience, the smartest path for most households is to choose a reliable monitor with published accuracy around a few percent, treat that as “good enough” for routine hydration decisions, and pair it with periodic targeted testing for specific contaminants when warranted by local conditions, well use, or health concerns.

Short FAQ

Can I rely on TDS alone to know whether my water is safe?

No. TDS is a powerful indicator of overall dissolved content, and multiple organizations, including WHO, EPA, and public health agencies, use TDS or conductivity as part of water-quality surveillance. However, TDS does not tell you which substances are present. Elevated TDS can hint at issues such as high sodium, nitrates, or sulfate, while low TDS can still hide trace contaminants like lead or pesticides. Use your smart TDS monitor as a screening and maintenance tool, but rely on utility reports or targeted lab testing to assess specific health risks.

My smart RO system shows 12 ppm some days and 16 ppm on others. Is that normal or a sign of trouble?

Small day-to-day changes at very low TDS values are usually normal and well within the expected accuracy of most meters. Flow rate, water temperature, and slight differences in sampling can easily create a few ppm of variation. What you want to watch for is a steady, long-term upward trend that pushes product water closer to the TDS of your feed water, or sudden jumps that coincide with other warning signs such as odd taste or reduced flow. In those cases, check the system’s prefilters and RO membrane and consider verifying readings with a handheld meter.

How often should I calibrate or verify a home TDS monitor?

Manufacturer instructions, such as those from HM Digital and the D-D TDS-3 documentation, recommend periodic calibration with a standard solution and recalibration after large temperature changes or heavy use. In practical terms, that often means verifying handheld meters a few times per year, and checking smart inline monitors when you change filters, notice unusual readings, or see a discrepancy between devices. If a meter always reads far from known standards or cannot be adjusted into range, replacement is a better choice than trying to work around a faulty instrument.

Smart TDS monitors are incredibly useful allies for better hydration at home, but they do not need to be perfect to keep you and your family well served. When you understand what TDS actually measures, how your monitor works, and how big its error really is in day-to-day terms, you can focus less on chasing tiny numerical differences and more on maintaining a trustworthy, comfortable, and health-supportive water system.

References

- https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/national-primary-drinking-water-regulations

- https://www.usgs.gov/publications/salinity-and-total-dissolved-solids-measurements-natural-waters-overview-and-a-new

- https://bostonreefers.org/forums/index.php?threads/how-to-calibrate-tds-meter.11436/

- https://www.lapl.org/neisci/kits/water-quality/why

- https://www.safewater.org/fact-sheets-1/2017/1/23/tds-and-ph

- https://blog.orendatech.com/understanding-total-dissolved-solids-tds

- https://www.theaquariumsolution.com/calibrating-tds-3-hand-held-tds-meter

- https://www.htt.io/learning-center/measuring-total-dissolved-solids-to-evaluate-water-quality

- https://onegreenfilter.com/what-tds-is-safe-to-drink/

- https://primelabmed.com/resource/how-to-calibrate-tds-tester?srsltid=AfmBOopeSNf6yzjHFjbzGdKBsSs0pM4Yg6W2xaRTer1TWmgVfuolIGuj

Share:

Why Cold-Water RO Systems Are More Efficient Than Hot-Water Setups

Why Cold-Water RO Systems Are More Efficient Than Hot-Water Setups