If you have ever clipped a TDS meter onto the waste line of your reverse osmosis (RO) system and watched the numbers jump higher than your tap water, it can be unsettling. As a Smart Hydration Specialist and Water Wellness Advocate, I hear some version of this concern every week: “Why is the TDS of my RO wastewater so high? Is something wrong with my filter? Is this hazardous for my family or my garden?”

The reassuring answer is that, in most cases, elevated TDS in RO wastewater is not a malfunction at all. It is a normal, even essential part of how RO protects your drinking water and the membrane itself. To use that wastewater wisely and safely, you just need to understand what TDS really measures, how RO works, and what the numbers are trying to tell you.

In this article, I will walk you through the science, share what I see in real homes and small businesses, and give practical, health-focused guidance on interpreting and reusing RO wastewater without anxiety or guesswork.

TDS 101: What Those Numbers Really Mean

Total Dissolved Solids, or TDS, is simply a measure of how much material is dissolved in your water. It includes minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and sodium; salts like chlorides and sulfates; trace metals; and a smaller contribution from organic matter and treatment chemicals. It is usually expressed in parts per million (ppm), which is numerically similar to milligrams per liter for most drinking water.

Several key points from reputable sources are worth keeping in mind.

The Environmental Protection Agency in the United States sets a non-enforceable “secondary” guideline of about 500 ppm TDS for public water systems. This is based on taste, scaling, and appearance, not on toxicity. The World Health Organization and various national agencies often describe water in the approximate range of 50 to 300 ppm as ideal for taste and general use, while water above about 1,000 ppm is frequently described as unpalatable.

A TDS meter cannot tell you which ions are present. It simply reports the total load of dissolved electrically conductive material. That means a reading of 800 ppm could be mostly benign calcium and magnesium, or a mix of sodium, chloride, and trace metals; the number alone does not define safety.

The Frizzlife and Water Quality Association materials emphasize that TDS is best thought of as a comfort and diagnostics parameter. It is very useful for tracking the performance of RO and other treatment technologies, but you should not treat it as a simple “good versus bad” score for health.

In short, TDS tells you how much dissolved material is there and helps you see whether your RO system is doing its job. It does not, by itself, tell you whether your water is safe or unsafe.

How Reverse Osmosis Splits Your Water Into Two Streams

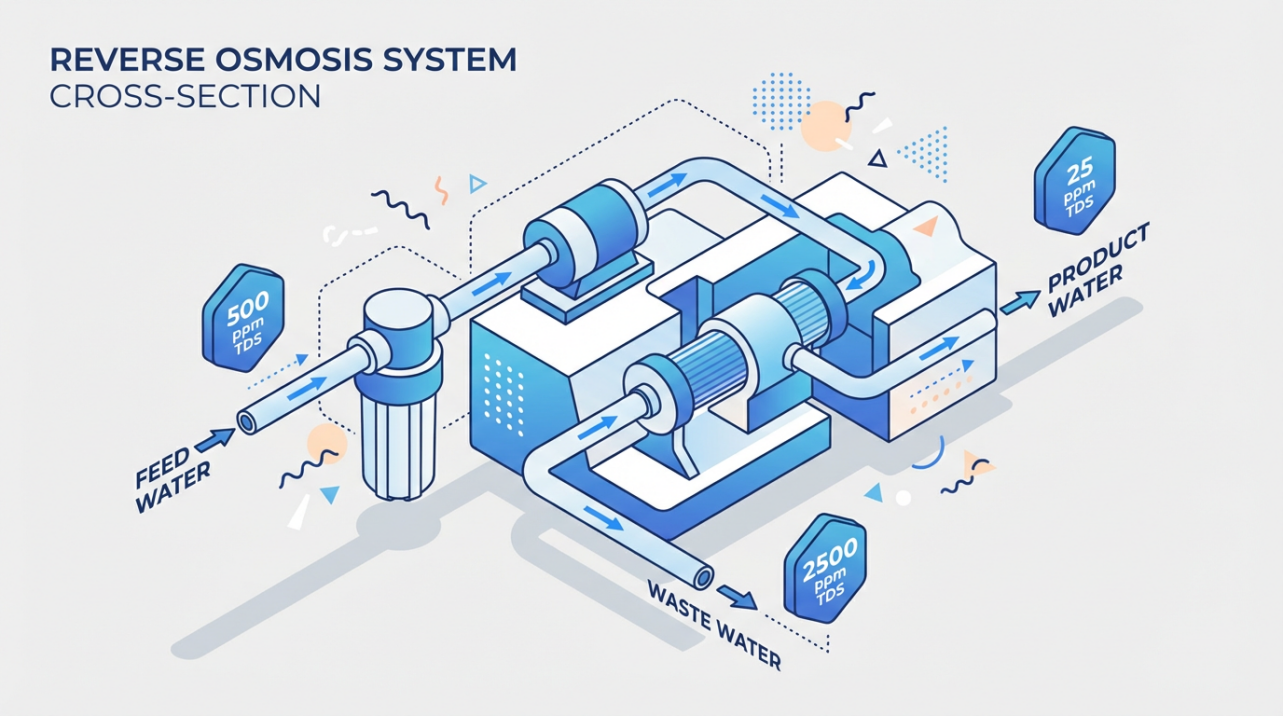

Reverse osmosis is one of the most powerful point‑of‑use filtration technologies available for homes and businesses. Sources such as Crystal Quest and the Water Quality Association describe RO as a pressure-driven process that pushes water through a semi‑permeable membrane with pores around 0.0001 micron, small enough to act like a molecular sieve. Water molecules pass; most dissolved ions and many contaminants are left behind.

A typical residential RO setup has several stages. There is sediment pre‑filtration to catch sand, rust, and silt. One or more carbon stages remove chlorine or chloramine and many organic chemicals that could damage the membrane or affect taste. The RO membrane then strips out the majority of dissolved salts, fluoride, nitrates, lead and other heavy metals, PFAS, and more. Some systems add a polishing or remineralization filter after the membrane to adjust taste and pH.

The RO membrane produces two streams at the same time. One is the permeate, or product water, which becomes your drinking and cooking water. The other is the concentrate, often called reject or wastewater, which carries away the salts, hardness, and other contaminants that have been rejected by the membrane.

Residential RO units commonly remove about 90 to 98 percent of TDS when they are in good condition, and high‑efficiency designs can approach about 99 percent. That means if your tap water comes in at 500 ppm, a healthy RO membrane will often deliver product water in the 5 to 50 ppm range, depending on the design and whether the water is remineralized for taste.

However, this purified water comes at a cost: to keep salts from building up on the membrane surface and causing scale or fouling, the system must continually sweep them away. That is exactly what the concentrate stream does. And that is why its TDS is higher than your feed water.

Why RO Wastewater TDS Is Higher Than Your Tap

To most people, the first surprise with RO wastewater is that the TDS is not just a little higher than the tap water; it can be several times higher. This seems backward until you remember that the purpose of the waste line is to collect what you do not want in your glass.

Industrial and commercial design guides from Puretec and AXEON show this clearly. Consider a feed water with 500 ppm TDS going into an RO system that recovers about 80 percent of the water as permeate. In that scenario, the remaining 20 percent leaves as concentrate. Because nearly all the dissolved material is now squeezed into that smaller stream, the concentrate TDS can jump to around 2,500 ppm, which is roughly five times the feed. If recovery is pushed to about 90 percent, the concentrate from the same 500 ppm feed can rise to around 5,000 ppm.

AXEON notes that in many designs, concentrate TDS is kept at roughly four times the feed TDS to manage scaling risk, and that antiscalant dosing is often recommended once concentrate TDS exceeds around 1,000 ppm. The point is that concentration, not contamination, is the reason waste TDS values look “high”.

This is by design. For the drinking water side to drop from hundreds of ppm down into the tens, the “reject” side must rise. The more efficiently the membrane removes TDS from the product stream, the more the concentrate number climbs relative to the feed.

When I test systems in homes with relatively hard well water, it is common to see feed water at 600 to 700 ppm, product water in the 40 to 60 ppm range, and wastewater well into the low thousands. That does not mean the wastewater suddenly became toxic. It simply reflects the physics of concentrating the minerals and salts that would otherwise be accumulating on your membrane or ending up in your coffee.

A Simple Comparison of Feed, Product, and Wastewater

It can help to see these relationships side by side. The figures below are drawn from the ranges reported by Puretec, AXEON, and residential RO performance guides, using a 500 ppm feed as a simple example.

Stream |

Example TDS (ppm) |

What it tells you |

Feed water |

500 |

Typical tap or well water going into the RO; minerals and salts are still present |

RO product |

5–50 |

About 90–99 percent reduction in TDS; suitable for drinking and cooking |

RO wastewater |

2,500–5,000 |

Salts and contaminants concentrated into the reject stream at 80–90% recovery |

The exact numbers in your home will differ, especially if your tap water TDS is higher or lower than 500 ppm or if your RO system is more or less efficient.

The important pattern is that healthy RO performance usually shows three things at once: the product TDS is dramatically lower than the feed, the wastewater TDS is significantly higher than the feed, and the ratio between feed and product TDS stays roughly stable over time.

Understanding Odd TDS Readings: Idle Time, Creep, and Meters

Sometimes, homeowners see RO readings that do not match expectations. A classic example is when an RO system has been sitting idle overnight. Manufacturers such as Bluevua describe a phenomenon called TDS creep, where small ions, especially sodium, diffuse across the membrane when there is no pressure pushing water through. When you first open the faucet after a long idle period, the first portion of product water can have a higher TDS than usual. As fresh water flows and full pressure is applied, the membrane’s normal rejection quickly reasserts itself and the product TDS drops to its steady range.

This is also why Bluevua and other manufacturers recommend discarding the first portion of water after prolonged inactivity before testing or drinking. For one of their tankless designs, they suggest pouring out roughly the first half of the carafe after an overnight standstill, because the sodium that crept across during the idle period temporarily bumps up the reading.

Delta Faucet’s technical guidance echoes this for systems with built‑in TDS indicators. Their documentation notes that a high TDS warning can appear when an RO unit has not been used for a while. Their remedy is simple: run the system for about ten minutes to flush the stagnant water, after which the TDS indicator should return to normal. They also point out that a properly functioning RO system typically delivers product water with TDS at about five to ten percent of the source water. When that ratio climbs toward around 15 to 20 percent, routine filter or membrane replacement is usually due.

Your wastewater readings can be affected by similar dynamics. If the system feeds a pressurized storage tank, the first waste flow when it restarts may not represent the typical concentrated brine, especially if valves and tank pressures cause brief mixing. TDS meters themselves introduce some noise as well. AXEON notes that handheld digital meters infer TDS from electrical conductivity and are typically accurate to about plus or minus two percent when properly calibrated.

For practical home monitoring, I encourage three simple habits.

First, always allow the RO to run a few minutes before taking measurements, especially after overnight or vacation downtime. Second, measure at consistent locations: one reading from the feed, one from the product, and one from the waste line if you want to track all three. Third, pay more attention to trends over months than to one-off numbers that may be influenced by temperature, contact time with a remineralization filter, or meter drift.

Is High-TDS RO Wastewater Dangerous?

RO wastewater often looks like a villain because its TDS reading is high, but context matters. Frizzlife describes residential RO concentrate as essentially concentrated tap water with elevated levels of the same salts, hardness, nitrates, and trace contaminants that were in the feed. It is generally not classified as hazardous in a household setting, but that does not make it ideal to drink.

Two main issues are taste and chronic exposure to specific ions. Water with TDS well above 1,000 ppm often tastes salty, bitter, or otherwise off. It can also leave visible white scale on fixtures and dishes and may accelerate buildup in pipes and appliances. The Frizzlife TDS overview notes that high TDS, especially when driven by sodium, calcium, and chloride, is associated with more scaling and can, depending on which ions dominate, contribute to long-term issues such as kidney stones or cardiovascular stress in susceptible individuals. That is one reason public standards treat 500 ppm as a reasonable aesthetic upper bound, even though health-based limits focus more on specific contaminants like nitrate or arsenic.

Because RO wastewater is typically several times higher in TDS than the feed, routinely drinking it would expose you to the higher end of your water’s mineral and salt profile. For people watching sodium intake, or for those with kidney or cardiovascular conditions, this is not desirable. Even for healthy individuals, it makes little sense to bypass the very membrane you installed to protect your drinking water.

For household equipment, high-TDS wastewater behaves much like very hard water. Running it through a kettle, humidifier, or espresso machine would accelerate scale formation. For plants, especially potted houseplants and salt-sensitive species, repeatedly irrigating with high-TDS water can cause salts to accumulate in the soil. The visible sign is a white crust on the soil surface or the pot, and the invisible effect is stress on the roots.

So while RO wastewater is generally non-toxic in the acute sense, it is not advisable as a primary drinking source, and it needs some smart handling for long-term health, appliances, and plants.

Smart Ways to Reuse RO Wastewater at Home

From a sustainability standpoint, the major downside of RO is water use. Traditional under-sink units can send two to four gallons of concentrate down the drain for every gallon of purified water produced. Newer high-efficiency and tankless systems tighten that ratio toward two-to-one or even close to one-to-one, but there is still a continuous stream of mineral-rich water leaving the membrane.

Frizzlife notes that a waste-to-product ratio around three-to-one can increase a home’s water bill by roughly twenty to thirty percent. The good news is that this wastewater is quite usable for many non-drinking tasks if you plan for it.

Some homeowners route the waste line into a storage container under the sink and then use that water for toilet flushing, floor mopping, pre-rinsing dishes, or pre-soaking laundry. Because TDS is largely about dissolved minerals, these uses are usually safe and can meaningfully reduce total water consumption. Concentrated tap water is perfectly adequate for flushing a toilet or swishing a mop.

Outdoor uses deserve a bit more care. Frizzlife and Crystal Quest both suggest that RO concentrate can be used for irrigating hardy, salt-tolerant plants or lawns, while cautioning against using it on delicate vegetables or sensitive ornamentals. A simple handheld TDS meter helps here. If your feed water is already near the upper end of acceptable TDS, the concentrate may climb into ranges that will gradually salt-stress many plants. Watching for signs like leaf tip burn and soil crusts is important.

One group that is already very familiar with TDS is aquarium hobbyists. Reef keepers and planted-tank enthusiasts often use RO or RO plus deionization to start with nearly zero-TDS water and then remineralize to the exact parameters their fish and corals need. Reef forums show users comparing TDS of feed, product, and waste as a way to evaluate their membranes. They consistently treat RO waste as unsuitable for aquarium use because its elevated TDS and unpredictable composition can destabilize water chemistry and stress livestock.

In my own field visits, I encourage clients to think of RO concentrate as “clean enough for cleaning” but not as drinking water or aquarium water. If you can capture and reuse even a portion of it for bathrooms, floors, or outdoor rinse jobs, you reduce the environmental footprint of your pristine drinking water.

When High Wastewater TDS Signals a Problem

Most of the time, high TDS in RO wastewater is a sign that your membrane is doing its job. However, there are scenarios where unusual TDS patterns, on both the product and waste side, point to problems.

Delta Faucet’s guidance gives a useful benchmark: for a healthy residential RO, the product water TDS should typically sit around five to ten percent of the source TDS. If your incoming water is 500 ppm and your product is reliably in the 25 to 50 ppm range after a good flush, the system is generally performing as intended, regardless of what the waste stream reads. Once that product ratio drifts up toward about 15 to 20 percent of the feed, it is time to replace filters or the membrane.

Wastewater TDS becomes more concerning when it does not rise as expected. If you measure feed, product, and waste and find that the waste TDS is only slightly higher than the feed, while the product TDS has climbed significantly, the membrane may be losing rejection capability. Scaling, fouling, or chemical damage from chlorine can create microscopic pathways that let ions leak into the product stream. Kurita and other membrane specialists describe how fouling and scaling reduce performance and change salt passage in complex ways, which is one reason regular maintenance and appropriate pretreatment matter.

Incorrect plumbing is another risk. The Delta Faucet troubleshooting notes specifically mention that misrouted hoses and wrong faucet connections can cause persistent high TDS readings in the “filtered” line. I have seen undersink installations where the waste and product lines were inadvertently swapped, sending high-TDS concentrate to the drinking faucet and low-TDS permeate down the drain. In such a case, product TDS will look suspiciously high, while the supposed waste water seems strangely clean.

High source TDS also shortens membrane life. Crystal Quest and the Water Quality Association emphasize the importance of feed-water quality for membrane longevity. When feed TDS is very high—think of private wells at 600 to 700 ppm or brackish supplies in the low thousands—the membrane faces a harsher osmotic and scaling environment. Pretreatment with softening, iron removal, or even nanofiltration may be needed, and membrane replacement intervals often shrink from the upper end of the two-to-five-year range toward the lower end.

If you are seeing rising product TDS, unexpectedly low waste TDS, or frequent clogging of pre-filters, it is wise to consult the system manual, check hose routing, and consider a professional evaluation. In many cases, replacing sediment and carbon pre-filters on schedule and protecting the membrane from chlorine with a good carbon stage, as recommended by the Water Quality Association and manufacturers, will prevent premature failure.

How to Measure and Interpret TDS Like a Pro

Monitoring TDS does not require a laboratory. A simple handheld digital meter, the same kind used by many water professionals and hobbyists, is enough to keep tabs on your system. AXEON notes that these meters typically measure conductivity, convert it to TDS using a factor, and provide readings with about plus or minus two percent accuracy when calibrated.

Start by establishing a baseline. Measure your feed water TDS at the kitchen sink, then measure your RO product after letting the system run for a minute or two to flush out any stagnant water. If you are comfortable, briefly capture some wastewater from the reject line and measure that as well. Jot these numbers down with the date.

What you want to see is a stable ratio. If your feed water hovers around 400 ppm and your product stays near 20 to 40 ppm after a flush, you are in that common five-to-ten-percent range that Delta Faucet and other sources describe as normal RO performance. If your waste water sits in the upper hundreds or low thousands, that is evidence that the membrane is successfully concentrating the dissolved solids you do not want in your glass.

Check again every month or two, or after any changes in taste, odor, or household plumbing. If the product TDS slowly creases over the course of a couple of years, you may be seeing natural membrane aging, and you can plan a replacement. If there is a sudden jump—to use an example from a homeowner case discussed by a water treatment expert, a shift from a typical 10 to 20 ppm product up to 70, 80, or 90 ppm overnight—investigate. It may be a legitimate membrane issue, or it may be a remineralization filter adding more minerals than expected, which raises TDS intentionally without indicating contamination.

Calibrating your meter with a standard solution every so often helps keep the data trustworthy. AXEON suggests monthly calibration and periodic cleaning of probes for professional setups. In a home, even occasional calibration and mindful use will give you a solid picture of how your system is aging.

Pros and Cons of High-TDS RO Wastewater

Looking specifically at wastewater, there are both benefits and drawbacks to its elevated TDS profile.

On the positive side, a concentrated waste stream demonstrates that your membrane is actively rejecting the minerals, salts, and contaminants that you installed it to remove. This concentrate stream flushes those substances away from the membrane surface, helping to prevent rapid scaling and fouling. Without that sweeping action, salts would crystallize on the membrane much more quickly, dramatically shortening its life and compromising product quality.

From a sustainability angle, the fact that RO wastewater is essentially concentrated tap water means you can repurpose it for many household tasks. As Frizzlife emphasizes, it is highly reusable for non-potable needs such as cleaning and flushing, provided you pay attention to TDS levels for plant use.

On the negative side, the water use impact is real. Traditional RO designs can discharge two to four gallons of concentrate for every gallon of product, and even high-efficiency systems still send an appreciable amount of water down the waste line. At the scale of a home, that shows up as a higher water bill. At the scale of a city or industrial plant, Puretec and others highlight the environmental and regulatory challenges of disposing of large volumes of brine, especially when concentrate TDS rises to several thousand ppm.

High-TDS wastewater also limits how you can reuse it. Appliances, fine plumbing, delicate plants, pets, and aquariums do not appreciate the elevated mineral and salt load. And because TDS does not specify which ions are present, you still need targeted testing or certified system performance data to know that specific health-related contaminants like lead or nitrate have been reduced to safe levels in your drinking water.

The bottom line is that high RO wastewater TDS is a trade-off. It is the price of low-TDS drinking water. Understanding that trade gives you the power to make smart decisions about reuse and system selection.

Putting It All Together for a Health-Focused Home

When you zoom out, the picture becomes clear. Reverse osmosis is designed to push dissolved solids away from your drinking water and into a separate stream. That concentrate stream naturally reads higher in TDS than your tap, sometimes several times higher. Far from signaling that your system is failing, this is usually a sign that it is working hard on your behalf.

To protect your family’s hydration and your home’s infrastructure, focus first on the quality of the product water: target a product TDS that is a small fraction of the feed, confirm that the system is certified for the contaminants you care about, and replace filters and membranes on the schedule recommended by the manufacturer and the Water Quality Association. Then, treat RO wastewater as a resource to be reused thoughtfully for cleaning and flushing, while respecting its limitations for drinking, appliances, and sensitive plants.

As someone who spends a lot of time in kitchens and utility rooms, I can say that the households most at ease with their water are not the ones chasing perfect zero readings on every meter. They are the ones who understand what the numbers mean, recognize that some TDS is normal and even beneficial, and use their RO systems as part of a balanced, sustainable approach to water wellness at home.

References

- https://www.ukaps.org/forum/threads/reverse-osmosis-water-relation-to-tds.36969/

- https://wqa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/2019_RO.pdf

- https://www.jeeng.net/pdf-93978-31506

- https://www.researchgate.net/figure/A-comparison-of-TDS-values-in-the-feed-water-and-the-RO-purified-water-of-Amritsar_fig2_328719407

- https://www.ecosoft.com/post/high-tds-levels-after-osmosis-why-is-this

- https://www.kuritaamerica.com/the-splash/membrane-fouling-common-causes-types-and-remediation

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41545-022-00183-0

- https://www.axeonwater.com/blog/understanding-why-total-dissolved-solids-tds-is-the-key-parameter-in-reverse-osmosis-system-design/

- https://bluevua.com/blogs/news/ro-system-tds-creep?srsltid=AfmBOoqyVIfeuXO1Q0NrrbkGVEn-lKxytvKSR1NweN3fykB19cnxzoYK

- https://www.cleanwaterohio.com/about-us/blogs/50357-understanding-tds-fluctuations-in-reverse-osmosis-systems-with-mineral-filters-why-its-safe-and-beneficial.html

Share:

Why 304 Stainless Steel Faucets Cost More Than Copper Faucets

Carbon Fiber Filters vs. Traditional Activated Carbon: Which Is Better For Your Home Water?