As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time inside people’s water systems – tracing pipes, checking pressure tanks, watching storage tanks fill and empty, and, just as importantly, listening to what taps and filters “say” when the flow is weak or suddenly drops off. One pattern never changes: when the discharge rate from a storage tank is wrong, everything else about your water experience feels off, from your kitchen RO faucet to your shower to your aquarium.

In this guide, we will look at what actually controls water discharge rate from storage tanks, using real-world insights from well and plumbing specialists, pressure-tank manufacturers, RO system experts, and even aquarium professionals. The goal is to help you understand what is happening inside the tank and plumbing so you can make smarter choices about design, maintenance, and upgrades to your home hydration system.

What “Discharge Rate” Really Means In A Home System

When homeowners describe a tank “not keeping up,” they usually mix two related but different ideas: how fast water comes out right now, and how long that flow can be sustained before the system runs out or pressure collapses.

Penn State Extension describes this clearly in the context of low-yield wells. Well yield is the maximum rate, in gallons per minute, that the well can deliver without the water level dropping below the pump intake. They point out that a one gallon-per-minute well can technically provide 1,440 gallons in a day, but over a two-hour peak window it can only supply about 120 gallons. A family of four can easily want more than 300 gallons in that same peak window, so the system will feel starved during busy times even though the daily volume looks fine on paper.

That same distinction applies to storage tanks and RO reservoirs. ESP Water notes that an under-sink RO system might produce water steadily at a slow rate, but the faucet discharge rate depends on how much pressurized water is stored in the tank and the pressure inside that tank. If the bladder is ruptured or the tank pressure is wrong, you may get about one cup of strong flow and then a thin trickle.

In practice, when we talk about discharge rate in storage tanks, we care about two things at once: the instantaneous flow at the tap or outlet, and the sustainable flow during your peak-use periods, such as a busy morning or a rapid sequence of RO draws in the kitchen.

How Tank Design Shapes Discharge Rate

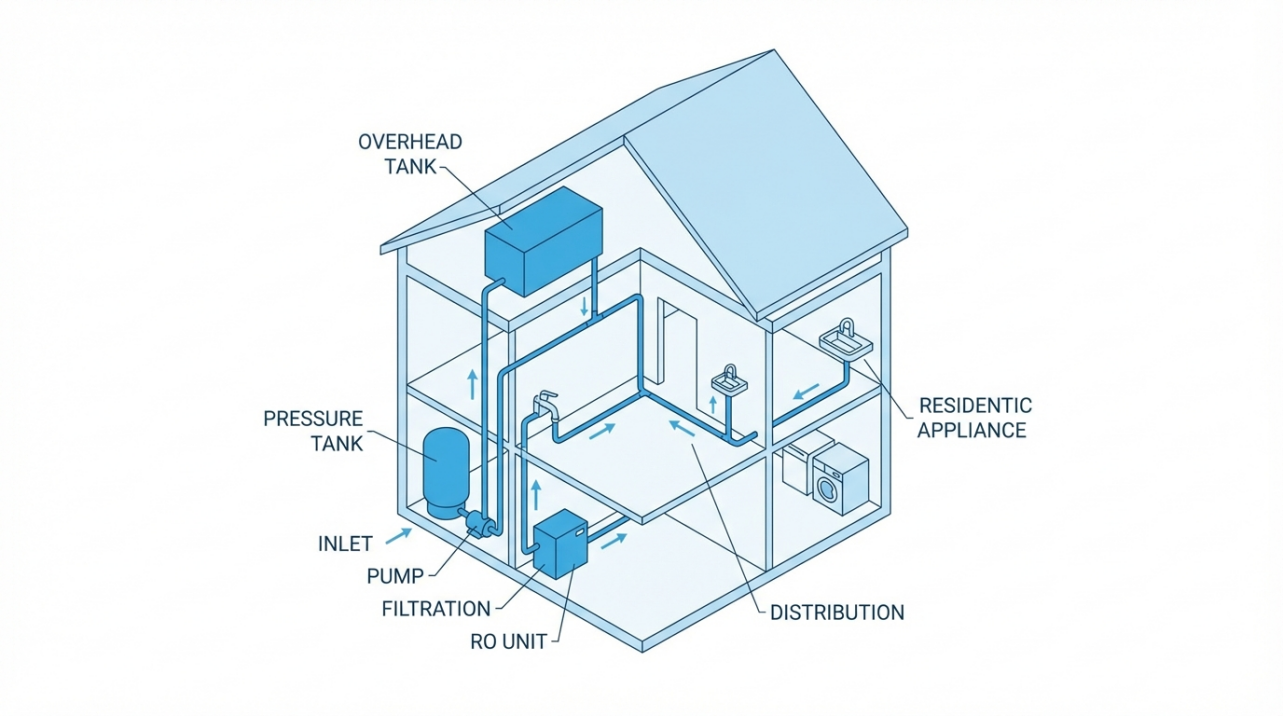

Storage tanks do not all behave the same way. A gravity-fed overhead tank on the roof, a well pressure tank in the basement, and a small RO storage tank under your sink may all be labeled in gallons, but the physics behind how they deliver that water to your fixtures differ in important ways.

To anchor the discussion, here is a simple comparison of common residential tank types and the main factors that control their discharge rate, based on guidance from Penn State Extension, WellManager, ESP Water, Pioneer Water Tanks America, and overhead-tank specialists.

Tank type |

What mainly drives discharge rate |

Typical issues seen in practice |

Gravity-fed overhead or loft tank |

Height difference and pipe restrictions |

Low pressure from limited elevation; sediment at outlet; blocked vents; undersized or old pipes |

Well pressure tank |

Pump capacity, pressure switch settings, air charge, well yield |

Short bursts of pressure followed by collapse; pump short-cycling; waterlogged or ruptured bladder |

RO storage tank (under-sink) |

Internal air bladder, precharge pressure, inlet pressure, filter condition |

Strong flow for a cup or two then a trickle; slow tank refill from clogged filters or low inlet pressure |

Intermediate storage cistern |

Tank volume versus daily and peak demand; booster pump sizing |

Tank running low during peak demand; under-sized booster; well unable to keep up without storage |

Gravity-Fed Overhead And Loft Tanks

Overhead-tank specialists at PAQOS emphasize that tank elevation is a core design variable. Increasing the height difference between the overhead tank and fixtures increases gravitational head and therefore pressure at your taps. Gravity-fed systems are mechanically simple, but discharge rate is limited by how much static pressure that height can generate and by any restrictions in the downstream piping.

Discussions from gravity-fed aquarium top-off systems underline the same point. In one example, a gravity-fed reservoir delivered enough flow to replace about two liters (roughly half a gallon) of daily evaporation even though the flow looked modest; the responder estimated that the existing setup could deliver closer to about 20 liters in a day (a bit over five gallons). The key insight was that for a top-off application, you do not need a dramatic jet of water; you need enough daily volume to comfortably match actual demand.

In a typical loft or attic tank feeding fixtures, discharge rate is controlled by three things that show up repeatedly in real cases:

Tank height relative to fixtures, which sets the basic gravity pressure. If that height is low, even wide-open valves will deliver a gentle flow.

Vent and outlet condition. A DIY Stack Exchange discussion on holding tanks points to blocked air vents as a primary cause when flow starts strong and then drops quickly. As water leaves, air must enter; if the vent or overflow, often protected by a fine mesh to keep out insects, is clogged by debris, the tank tries to pull a partial vacuum and flow diminishes sharply.

Pipe health and layout. PAQOS, Transou’s Plumbing & Septic, and Strada Services all describe how mineral buildup, sediment, and old or undersized piping restrict flow from any tank. Over time, the inside of a pipe can choke down like “plumbing cholesterol,” meaning even a properly elevated tank will discharge sluggishly.

Pressurized Well Tanks And Bladder-Based Storage

In pressurized systems, discharge rate at fixtures is mainly governed by the pressure tank and its controls, not by gravity. WellManager notes that most homes are designed for around 50 to 60 pounds per square inch of pressure at the fixtures, while outdoor drip irrigation often runs at only 20 to 30 pounds per square inch. The pressure tank stores water at these pressures so the pump does not have to start every time someone opens a faucet.

Pressure tanks rely on a cushion of air separated from the water by a flexible bladder or diaphragm. Fresh Water Systems explains that the ideal precharge pressure for an empty well pressure tank is about 2 pounds per square inch below the pressure switch’s cut-on setting. For a 30/50 switch, this means setting the tank at about 28 pounds per square inch when there is no water inside. If the bladder fails or the air charge is wrong, the tank will not deliver its intended drawdown, leading to short bursts of strong flow followed by rapid pressure loss and constant pump cycling.

ESP Water describes a similar bladder-based design in small RO storage tanks. They recommend 7 to 8 pounds per square inch of air pressure in an empty RO tank. Their troubleshooting guide notes that when a tank bladder ruptures, you may get about one cup (8 ounces) of normal flow from the RO faucet, followed by a sudden drop to a small stream. In that case, the only solution is to replace the tank.

Q&A guidance for unsteady water flow from JustAnswer plumbing experts echoes these procedures. To assess pressure tank performance, they advise turning off the pump, relieving system pressure, using a tire gauge on the valve stem at the top of the tank to read the air charge, and adding air carefully if needed. After refilling, checking the pressure after a short rest period can reveal a leaking bladder if the air charge has dropped significantly.

Intermediate Storage Tanks And Cisterns

For homes with low-yield wells, discharge rate at the tap often depends more on storage design than on raw well output. Penn State Extension and Pioneer Water Tanks America both highlight an approach where a large above-ground or buried storage tank acts as a buffer. The well pumps slowly into this intermediate tank more or less around the clock, while a separate pump and pressure tank deliver stable household pressure.

Penn State Extension suggests sizing residential intermediate storage so it can hold roughly a full day of water use, around 100 gallons per person. They note that 300 to 500 gallon tanks are common for homes and that tanks can be placed in parallel for maintenance flexibility. Pioneer Water Tanks America similarly emphasizes that storage should be sized to cover drinking and domestic needs, plus a reserve for above-average use and emergencies.

WellManager provides a concrete example: a low-yield well that produces about one gallon per minute can only supply 120 gallons in a two-hour peak window, while a typical home might want about 300 gallons in that time. A storage tank of around 300 gallons bridges that gap, so the well does not have to keep up with peak demand moment by moment. In that scenario, discharge rate during peak use is controlled by the booster pump and pressure system drawing from stored volume, not by the raw well yield.

Restrictions And Blockages: When Flow Starts Strong And Then Fades

Many homeowners describe the same symptom: the tank is full, the first few seconds of flow are strong, and then everything slows to a trickle. Across plumbing forums, well guides, and tank troubleshooting resources, three recurring culprits emerge: air vent problems, outlet and line blockages, and partially closed valves or fittings.

Air Vents And Vacuum Lock

The DIY Stack Exchange discussion on diminishing flow from a holding tank explains why air vents are so critical. As water flows out, air must enter to replace it. If the tank’s air vent, sometimes implemented as the overflow outlet with a mesh screen, becomes obstructed by vegetation, insect nests, shells, or other biological debris, a partial vacuum forms. That vacuum resists further outflow, so discharge rate drops rapidly even though plenty of water remains in the tank.

Because vent screens are easier to access than the tank interior, the advice from that discussion is to inspect and clean vents regularly as part of routine maintenance. This aligns with broader recommendations from well and storage tank specialists who stress that vent openings should be protected from insects but still allow free air movement.

For anyone who maintains aquariums, this pattern is familiar in a different context. LiveAquaria and Aquarium Co-op both describe “dead spots” where water is not circulating well, leading to accumulation of gases and debris. In tanks, adding or repositioning circulation devices fixes those dead spots. In storage tanks, making sure the air vent can “breathe” plays a similar role in preventing a vacuum that chokes discharge.

Sediment, Sludge, And “Plumbing Cholesterol”

DIY Stack Exchange and Pioneer Water Tanks America both note that material accumulating at or near the tank outlet can restrict flow. In holding tanks, sludge, sediment, or rust flakes can settle at the bottom and partially block the outlet opening. Once debris enters the supply line, it tends to lodge at bends, valves, regulators, or filter housings, narrowing the passage.

Transou’s Plumbing & Septic and Strada Services describe a similar phenomenon in distribution piping, especially in older systems or hard-water areas. Minerals and sediment gradually coat pipe interiors, shrinking the effective diameter and increasing resistance to flow. They liken this to “plumbing cholesterol,” a slow process that eventually makes normal fixtures feel weak even at normal pressure.

Gravity-fed tanks are particularly prone to sediment around outlets because flow velocities are low; particles can settle easily. Pioneer Water Tanks points out a small silver lining: storage tanks, especially large ones, allow heavier particles to settle at the bottom, and water taken from higher in the tank is often cleaner, which helps protect downstream filters. However, that benefit depends on regular maintenance to manage the settled layer.

The practical takeaway is that a full tank is not a guarantee of good discharge. The path from the tank interior through the outlet, valves, and piping must be clear. When discharge rate falls over time, inspections often start at the vent and outlet, then move outward toward filters and fixtures.

Partially Closed Valves And Restrictive Fittings

Sometimes the problem is surprisingly simple. The DIY Stack Exchange thread on diminishing flow and Strada Services’ guidance on low household pressure both mention partially closed valves as a common, easy-to-miss cause. A quarter-turn shutoff that is not fully open or a pressure-regulating valve adjusted too low will make the system feel like the tank is underperforming when the restriction is purely mechanical.

The Screwfix cold-tank discussion adds another practical nuance: fittings and connectors themselves can be points of restriction, especially in older plastic systems with mixed pipe sizes. When diagnosing slow flow from a loft tank, the homeowner in that thread planned to progressively disconnect accessible connectors and check whether any were blocked or damaged.

From a smart hydration perspective, these are the simplest checks and should be done early: verify that isolation valves and the main shutoff are fully open, check that any pressure regulators are set appropriately, and confirm that no one has “throttled” a valve to quiet noise or reduce splash and then forgotten about it.

System Capacity, Peak Demand, And Tank Sizing

Even if every vent, outlet, and pipe is pristine, the discharge rate you experience at the tap can still be inadequate if the system simply does not have enough capacity to cover peak demand. The research on low-yield wells and intermediate storage provides a clear framework for thinking this through.

Penn State Extension emphasizes that peak demand, typically 30 minutes to two hours in the morning or evening, is the critical design window for homes. A system should at least be able to meet two hours of peak use. Their example shows that a one gallon-per-minute well can generate enough water over 24 hours, but without storage it cannot meet a two-hour window where the home may want more than 300 gallons.

To solve this, they describe two complementary strategies: reducing peak use through conservation and scheduling, and increasing storage. On the conservation side, they mention shifting some showers to evenings, spreading laundry through the week, and installing water-saving devices such as front-loading washers and low-flush toilets, which can reduce total household water use significantly and save money on water-heating energy.

On the storage side, they detail how pressure tanks by themselves provide only limited usable water. For example, a 42 gallon pressure tank might yield about 8 gallons of actual drawdown, an 82 gallon tank about 16 gallons, and a 120 gallon tank about 24 gallons before pressure falls to the cut-in point. These volumes are not enough on their own to correct low-yield problems, which is why intermediate storage is often needed.

Intermediate storage systems use large, nonpressurized tanks, often in the 300 to 500 gallon range for homes, fed continuously by the well. A separate pump and pressure tank then supply the house. Pioneer Water Tanks America and WellManager describe this approach as a buffer that decouples household demand from well yield. WellManager goes further and notes that raising pressure or adding a larger pressure tank without adding storage does not fix a low-yield well and can actually increase stress on the source.

Specialists like Goold Wells & Pumps add that, when yield is the limiting factor, more aggressive interventions such as deepening the well or hydrofracking may be considered, but only after careful professional evaluation and in line with local regulations and geology.

For homeowners focused on clean drinking water and smart hydration, the important point is that storage tank discharge rate is never just about the tank. It sits inside a larger balance between source capacity, storage volume, booster pump sizing, and peak demand patterns.

Filtration, Fixtures, And Home Hydration Appliances

Many slow-flow complaints in kitchens and bathrooms trace back not to the storage tank, but to what happens after the tank: filters, membranes, cartridges, faucet aerators, and showerheads.

ESP Water emphasizes that clogged filters are probably the most common reason for slow reverse osmosis water flow. Sediment, carbon block, and polishing filters all gradually accumulate debris from source water. If they are not replaced on schedule, they throttle the amount of water that can reach and leave the RO storage tank. ESP Water recommends annual filter changes for typical conditions, with more frequent changes, even every six months, when water quality is poor.

Their troubleshooting guide walks through how to measure production: open the RO faucet in a locked-open position, wait until only a slow drip or very slow flow remains after the lines empty, then collect water for 60 seconds. The volume you collect in that minute can be scaled up to estimate daily production; they give an example where producing 4 ounces per minute equates to about 45 gallons per day, or roughly 1.875 gallons per hour. If actual production is significantly below the system’s rating, clogged filters or a fouled membrane are prime suspects.

On the fixture side, Strada Services and Transou’s Plumbing & Septic describe how mineral scale and soap scum often build up directly in showerheads and faucet aerators, reducing perceived pressure even when system pressure is normal. Strada recommends soaking fixtures in vinegar for at least 30 minutes, scrubbing, and flushing to clear deposits. They also suggest flushing household plumbing periodically by running all fixtures at full flow to dislodge sediment.

In all of these cases, the storage tank is doing its job. It is the downstream resistance imposed by filters and fixtures that cuts discharge rate at the point of use. For anyone trying to deliver crisp-tasting water from a smart filtration setup, this is both good news and a design responsibility. Filters are critical for health, but they must be sized, installed, and maintained with flow in mind.

Simple Diagnostics To Understand Your Tank’s Discharge Performance

From a homeowner’s perspective, one of the most empowering steps is to measure and observe water behavior rather than guessing. Several of the sources provide practical diagnostic approaches that do not require specialized tools beyond a measuring cup and a tire gauge.

ESP Water’s one-minute collection test for RO systems is a perfect example. By locking the faucet open, waiting until the system settles into its natural production drip, and measuring the ounces collected in one minute, you gain a concrete number you can compare over time. If you repeat this test every six or twelve months, a declining production rate is an early warning that filters or membranes are restricting flow.

Pressure tank specialists at Fresh Water Systems and JustAnswer plumbing highlight another simple test: checking bladder air pressure with a standard tire gauge at the valve stem. With the pump off and the system depressurized, the reading should match the manufacturer’s specification, which is typically a couple of pounds per square inch below the pressure switch cut-in. If the reading is too low, careful topping up and rechecking after a rest period will tell you whether the bladder can still hold air. If air pressure falls quickly, the bladder is likely compromised, and the tank will not be able to deliver its intended discharge profile.

For gravity-fed tanks, the DIY Stack Exchange advice suggests visually inspecting and cleaning air vents and overflow screens and checking around the outlet inside the tank, if accessible, for sediment and sludge. When flow starts strong and then drops off within a few seconds, a blocked vent is a particularly strong suspect.

Plumbing and home service companies such as Strada Services and Transou’s Plumbing & Septic stress a few simple whole-house checks that apply to almost any setup. Confirm that the main shutoff and key isolation valves are fully open. Look and listen for leaks around toilets, washing machines, and water heaters. Pay attention to whether all fixtures are weak or only specific ones; localized issues often point to fixture-level or branch-line restrictions rather than a storage tank problem.

When these basic checks do not identify an obvious cause, or when symptoms suggest deeper supply issues like falling well yield or pump malfunction, experienced well and plumbing contractors become essential.

Goold Wells & Pumps and WellManager both describe the use of professional diagnostics such as measuring static and pumping water levels, testing recovery time, and evaluating pump sizing relative to system demand.

FAQ: Common Questions About Storage Tanks And Discharge Rate

Why does my storage tank start with strong flow and then slow to a trickle?

This pattern is classic in two situations described across the sources. In gravity-fed holding tanks, the DIY Stack Exchange discussion points to blocked air vents or overflow openings. As water begins to flow, the tank can initially push water out, but without a clear vent for air to enter, a partial vacuum quickly forms and throttles discharge. Cleaning or repairing the vent often restores normal flow.

In pressurized RO tanks, ESP Water notes that a ruptured internal bladder behaves similarly from the user’s perspective. You may get about one cup of normal flow before it drops to a small stream. In that case, because the bladder cannot be repaired, the only fix is to replace the tank. Clogged filters can also cause slow or fading flow by limiting how much water the tank can deliver over time, even if the bladder is intact.

Does a bigger storage tank always mean better discharge rate?

Bigger storage usually means more volume, not necessarily better discharge rate. Penn State Extension explains that increasing pressure tank size on a low-yield well adds some drawdown but may still not cover peak demand, because a pressure tank’s usable volume is only a fraction of its total capacity. They give examples where a 42 gallon pressure tank provides about 8 gallons of drawdown, and even a 120 gallon tank provides about 24 gallons, which cannot compensate for a well that cannot keep up during peak periods.

WellManager and Pioneer Water Tanks America show that large intermediate storage tanks, sized around daily use, do improve practical discharge because they allow a booster pump to deliver consistent pressure during peak times. However, even there, discharge rate at the tap is controlled by the booster pump and pressure settings, not purely by how many gallons the tank holds. In short, storage volume, pump design, and source capacity all need to be aligned.

How can I tell if low flow is a pressure problem or a yield problem?

WellManager and Goold Wells & Pumps both emphasize that most “pressure” complaints actually stem from supply or yield issues rather than true low pressure. If pressure seems fine when using a single fixture but collapses when several fixtures run together or after a short period, that points toward limited supply or storage. The Penn State Extension example of a one gallon-per-minute well struggling during a two-hour peak window is a good illustration of this pattern.

True pressure problems, by contrast, often show up as uniformly weak flow at all fixtures regardless of how many are running. Strada Services and Transou’s Plumbing & Septic highlight causes such as clogged filters, corroded pipes, partially closed valves, failing pressure regulators, or malfunctioning pressure switches. In many cases, a professional well or plumbing contractor will use pressure gauges and flow tests at different points in the system to distinguish between supply, storage, and distribution issues.

A well-designed storage tank is the quiet heart of a healthy home hydration system. When elevation, pressure, venting, piping, filtration, and storage volume are all working together, you see it in simple everyday moments: an RO faucet that fills a glass briskly, a shower that feels consistent, and a well that keeps up with your family’s routine. By understanding the specific factors that control discharge rate and using evidence-based checks from trusted well, plumbing, and water-treatment experts, you can tune your system for both performance and long-term reliability.

References

- https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=8547&context=masters_theses

- https://extension.psu.edu/using-low-yielding-wells/

- https://www.uml.edu/docs/Gravity-Overview_tcm18-190104.pdf

- https://www.ukaps.org/forum/threads/water-circulation-in-planted-tank.50354/

- https://www.ultimatereef.net/threads/need-to-increase-flow-from-gravity-fed-tank.909920/

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/why-reverse-osmosis-water-flow-is-slow?srsltid=AfmBOop2BbwCt4Tewx8K0qwQZnZj0H7_Z0PnbIncXOhiTXqqf4Mte_17

- https://www.gooldwells.com/troubleshooting-low-well-water-pressure-causes-and-solutions/

- https://www.justanswer.com/plumbing/19ror-typical-system-pressurized-water.html

- https://pioneerwatertanksamerica.com/solve-water-well-pressure-problems-with-a-water-storage-tank/

- https://terrylove.com/forums/index.php?threads/low-producing-well-storage-tank.72497/

Share:

Understanding Why Your RO System Sometimes Refuses to Operate

Understanding Why Your Pump Starts But Lacks Pressure