As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time under kitchen sinks. One of the most common worries I hear is a variation of the same question: “Why is my reverse osmosis system always running water down the drain? Is that normal, and what is it doing to my water bill and the environment?”

Reverse osmosis (RO) is one of the most powerful tools we have for clean, great-tasting drinking water. But it comes with a side effect: a wastewater stream that can be either a healthy part of the process or a sign that something is seriously wrong. Understanding the difference is the key to a system that protects both your health and your water resources.

In this article, I will unpack what “continuous wastewater discharge” really means in RO systems, how much wastewater is normal, why a home unit might drain nonstop, how that affects filter life and the environment, and what you can do to reduce waste without sacrificing water quality.

How RO Works And Why There Is Wastewater At All

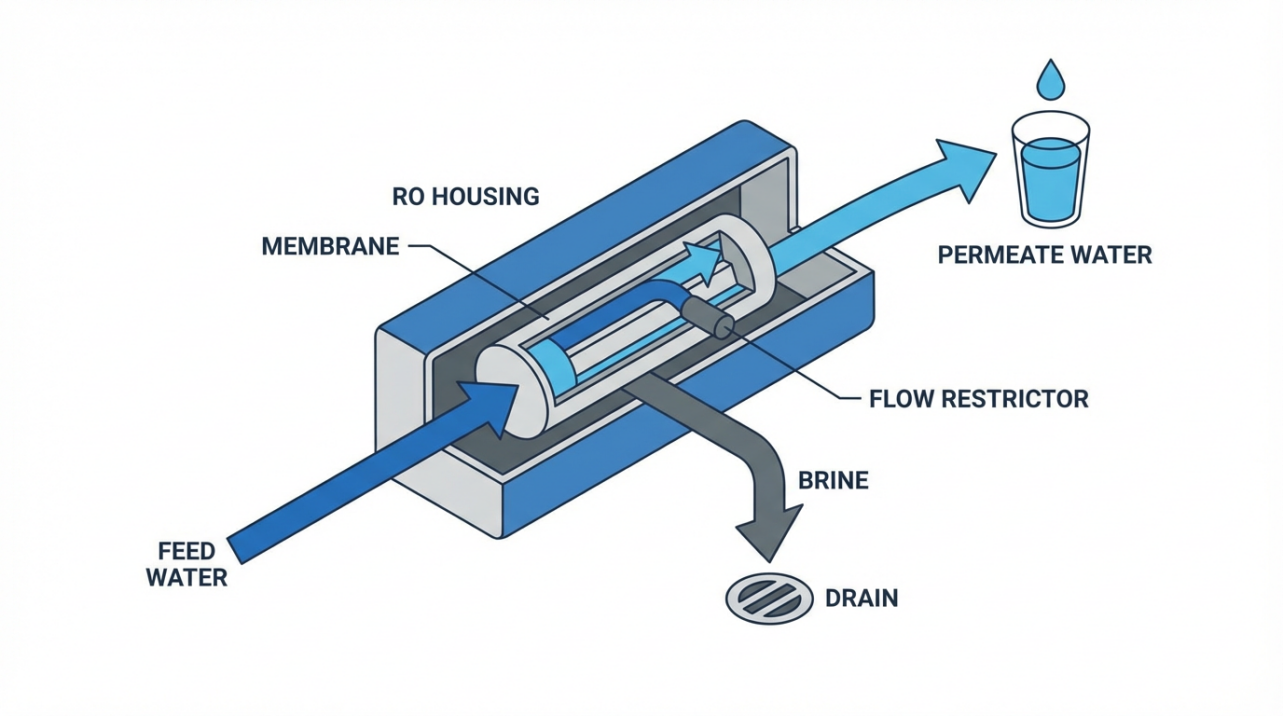

Reverse osmosis is not a simple “filter.” As explained by Puretec Water and several technical texts on the basics of reverse osmosis, RO uses a semi‑permeable membrane and pressure to separate water into two streams.

The incoming feed water is pushed across the membrane. On one side you get permeate, the purified drinking water that has passed through the membrane. On the other side you get concentrate, often called brine, reject, or simply the drain stream. This concentrate carries away most of the dissolved salts, organics, and microbes that the membrane rejects.

Unlike a pitcher filter where all the water eventually passes through the media, RO is cross‑flow filtration. A continuous concentrate stream sweeps along the membrane surface while product water passes through. That sweeping action is deliberate. It helps prevent contaminants from building up on the membrane and reduces fouling.

Designers describe RO performance in terms of salt rejection and recovery. Puretec Water notes that well‑designed systems often reject around 95 to 99 percent of dissolved salts. Recovery is the fraction of feed water turned into permeate. If an RO plant operates at 80 percent recovery, roughly four gallons out of every five become product water and one gallon becomes concentrate. Under those conditions, the concentrate may hold around five times the salt level of the feed because all the rejected salts are packed into that smaller volume.

At larger industrial or municipal scales, this concentrate becomes a significant brine management challenge. Studies reported by Genesis Water Technologies, Racoman, and scientific work on RO brine composition show that brines from high‑recovery systems can have very high hardness and salinity and can trigger scaling, fouling, and environmental toxicity if not handled carefully.

At the scale of a single under‑sink system, the volumes are small, but the same physics apply.

There will always be a drain line, and it will always run while the system is actively making water. That is normal. The question is whether it shuts off when it should.

How Much Wastewater Is Normal For A Home RO System?

Here is where expectations and reality often collide.

The US Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense program evaluated household point‑of‑use RO systems and found that a typical unit can send five gallons or more of reject water down the drain for every gallon of treated water produced. The most inefficient designs can waste up to ten gallons per gallon of drinking water. To qualify for the WaterSense label, an under‑sink RO must be independently certified to use no more than about 2.3 gallons of drain water per gallon of treated water.

By contrast, consumer guidance from Frizzlife describes many residential RO units as wasting about two units of water for every unit of purified water. Both viewpoints can be true. High‑efficiency modern systems are much better than older, unlabeled designs, and real‑world performance depends heavily on pressure, membrane condition, and configuration.

It helps to translate these ratios into something tangible. Imagine your household uses two gallons of RO drinking and cooking water per day. With a waste ratio of ten gallons to one gallon of product, you would be sending roughly twenty gallons down the drain daily, or about 7,300 gallons a year. At a five‑to‑one ratio, the annual drain volume drops to about 3,650 gallons. At a WaterSense‑qualified ratio near 2.3, those same two gallons of daily RO water translate to roughly 1,700 gallons of wastewater per year.

This simple calculation lines up well with the EPA’s own estimate that replacing a conventional under‑sink RO with a WaterSense‑labeled model can save more than 3,100 gallons of water per year, or about 47,000 gallons over the lifetime of the system.

So some amount of intermittent wastewater discharge is expected and can be managed with better equipment choices. Continuous discharge, especially hours after you last used the RO faucet, is a different story.

Water eStore’s troubleshooting guidance for home RO systems points out a critical rule of thumb: it is normal for water to run to drain while the tank is filling, but after three or four hours of zero water usage there should be no water running to the drain. If the drain line is still flowing loudly long after you last drew water, your system likely has a malfunction.

The Shut‑Off Heart Of Your RO: Valves, Pressure, And The Storage Tank

To understand continuous wastewater discharge, you need a quick tour of the components that tell an RO system when to stop.

Most under‑sink systems use a pressurized storage tank. Inside that tank is an air bladder. When the tank is empty, the air side is pre‑charged to a low pressure, typically around seven to eight psi when measured with the tank drained and isolated, as explained in NU Aqua Systems’ troubleshooting guide. As water fills the bladder, the air compresses and the water pressure at the tank outlet rises.

This rising back pressure is the signal that should trigger shut‑off. Two key parts respond to it. The first is the check valve, which ensures water can flow toward the tank but not back toward the membrane and drain. The second is the automatic shut‑off valve, often called an ASO. Puretec and troubleshooting content from NU Aqua and Water eStore all describe the ASO as the device that uses pressure on the tank side versus the feed side to decide when to stop supply water from entering the system.

Many high‑end systems add a permeate pump. APEC Water’s RO‑PERM guides explain that in these designs, the pump itself incorporates a shut‑off function. When it fails, the waste stream can run non‑stop even if the check valve is fine.

All of this depends on adequate incoming pressure. Water eStore notes that a typical ASO needs at least about forty psi of feed water pressure to close reliably. NU Aqua’s specifications for the Platinum Series five‑stage system call for an operating range around forty‑five to eighty psi. Frizzlife describes many residential units as working best between about fifty and eighty psi. Below that, the system may never develop enough differential pressure for the valves to sense a “full tank” condition.

When everything is healthy, the chain looks like this: feed water pressure drives water across the RO membrane, the tank fills, back pressure rises, the ASO senses the pressure balance, the check valve holds water in the tank, and both production and wastewater flow shut off.

When something breaks in that chain, the drain can run essentially continuously.

Why Your Home RO Might Be Draining Nonstop

From field experience and the troubleshooting guides published by NU Aqua Systems, Water eStore, and APEC, the most common causes of continuous wastewater discharge fall into three broad categories: pressure and tank issues, faulty shut‑off components, and flow restrictions or leaks.

Tank Pressure Problems And Overfilling

If the air charge in your storage tank is too low, the tank behaves like a soft balloon. It keeps accepting water but does not build enough back pressure to signal the ASO valve. NU Aqua explains that to check and set tank pressure correctly you shut off the feed water, fully drain the tank through the faucet, and then measure the air pressure with a simple tire gauge on the tank’s Schrader valve. If the tank is empty and the pressure is not around seven to eight psi, you adjust it with a bicycle pump or compressor.

If the pressure is too high when empty, the tank will never fill completely and you will notice low storage volume and rapid cycling. If it is too low, the RO may run longer than it should and can sometimes fail to shut off altogether. Many homeowners discover during this test that the tank bladder has failed, in which case the tank must be replaced rather than re‑pressurized.

Faulty Check Valve, ASO Valve, Or Permeate Pump

A stuck or broken check valve is one of the classic reasons for nonstop drainage. Water eStore and NU Aqua both describe the same phenomenon. If the check valve fails, water stored in the tank can backflow toward the membrane and out the drain line whenever the feed water is shut off. That means the system can waste water even while you are away, draining the tank backward through the membrane and sending it to the sewer.

The ASO valve is the other common culprit. If its internal diaphragm or seals are damaged, it may never fully close, so feed water continues to push across the membrane and down the drain even when the tank is at full pressure. NU Aqua suggests a simple behavior check: start with a full tank, draw two to three glasses of water from the faucet, and then close the tank valve and any refrigerator or ice‑maker lines. That simulates a full tank with no outlet. After three to five minutes, the drain line should stop running. If it does, the check valve and ASO are probably fine. If it does not, at least one of those parts is defective.

APEC’s RO‑PERM technical support adds another twist. In systems with a permeate pump, that pump has its own internal shut‑off function. Their guidance shows that if you repeat a similar test and no water flows from the drain line when you have feed off and the tank open, the check valve is likely fine. In that case, a failed permeate pump can be the part that allows the waste stream to continue.

Clogged Filters, Worn Membrane, Or Leaks On The Outlet

RO systems live and die by pressure and flow. NU Aqua’s troubleshooting guide highlights that severely clogged pre‑filters or a fouled membrane can interfere with proper pressure sensing and cause symptoms that look like continuous drainage. If your filters or membrane have not been changed in years, this is one of the first things to address.

Maintenance schedules vary by manufacturer. NU Aqua recommends replacing pre‑filters and post‑filters roughly every six months and membranes about every twelve months, depending on water quality and usage. APEC Water’s guidance for under‑sink units suggests annual changes for the three pre‑filters and every three to five years for the membrane and polishing filter, again depending on conditions. Axeon Water points to a range of about six to twelve months for pre‑filters and around two years for membranes in many industrial and light commercial settings. A do‑it‑yourself forum contributor using a TDS meter to track performance recommended replacing the membrane when its rejection rate drops to around seventy‑five percent.

One simple example shows how TDS testing can reveal trouble. In that forum discussion, a tap water TDS of 160 ppm and RO water at 12 ppm corresponded to about ninety‑two percent rejection, calculated as the difference divided by the feed value. If, over time, the RO outlet TDS climbs so that you are only removing three‑quarters of the dissolved solids, the membrane is no longer doing its job efficiently. That same deterioration can be accompanied by pressure changes that affect shut‑off behavior.

Finally, leaks on any of the RO outlet lines can keep the system running. APEC warns that if your RO feeds a second or third output, such as an ice maker or a remote faucet, even a small leak in those lines can prevent pressure from building up enough to shut the system down. The system “thinks” someone is always drawing water, so it keeps producing and sending wastewater to the drain.

Safe At‑Home Checks To Confirm A Continuous Discharge Problem

When you suspect your RO drain is running more than it should, a few careful checks can help you distinguish between normal operation and a true malfunction. These steps are drawn from the troubleshooting guides of NU Aqua Systems, Water eStore, and APEC Water. If you are not comfortable working with plumbing, however, it is always wise to consult a professional.

A practical first check is the simulated full‑tank test. Start by letting your RO system run until the faucet output drops to a slow trickle, which indicates the tank is full. Then draw two or three glasses of water from the RO faucet to make the system start refilling. Immediately close the shut‑off valve on the tank and close any valves feeding a refrigerator or ice maker. You have now told the system that the tank is full and there is nowhere for water to go. Over the next three to five minutes, watch or listen to the black drain line where it connects to the drain saddle on your sink drainpipe. If the drain flow slows and stops, your shut‑off assembly is likely working. If the drain line continues to run steadily, you have a real continuous discharge issue.

To distinguish between a bad check valve and a bad ASO or permeate pump, you can adapt the test used by NU Aqua and APEC. With plenty of water in the storage tank and the tank valve open, turn off the cold feed water supply to the RO unit. This might be a small angle stop valve under your sink or a ball valve on the feed line. Place a cup or container under the black drain line and carefully disconnect it from the drain saddle. Then open the RO faucet to relieve any residual pressure. If water continues to flow out of the disconnected black drain tubing, that water is coming from the storage tank. In that case, the check valve is not doing its job and is allowing backflow from the tank to the drain. If no water drains from that line with the feed off and tank open, the check valve is intact and the fault likely lies in the ASO valve or, in permeate‑pump systems, in the permeate pump’s internal shut‑off.

A separate but complementary check is to verify tank pressure. Shut off the feed water, open the RO faucet, and allow the tank to completely drain. Then close the faucet, isolate the tank by closing its shut‑off valve, and remove the small cap on the air valve at the bottom or side of the tank. Using a tire pressure gauge, measure the air pressure. If it is far below seven to eight psi, add air gradually with a bicycle pump until it reaches that range, checking periodically. If air and water both come out of the valve, the tank bladder is likely ruptured.

Finally, if you own a TDS meter, take ten to twenty minutes with the tank valve closed and the faucet barely open so that only the membrane is feeding water. Then measure the TDS of that trickling water and compare it to the TDS of your tap water. Using the method discussed in the do‑it‑yourself forum, you can calculate the rejection percentage. If the rejection has fallen significantly compared to when the system was new, consider replacing the membrane even if it is not yet past the nominal age suggested by the manufacturer. Membrane performance, pressure behavior, and waste flow are tightly linked.

What Continuous Wastewater Discharge Does To Your Filters, Bill, And Environment

From a smart hydration perspective, nonstop drainage is more than just an annoyance. It has measurable effects on operating cost, component life, and sustainability.

APEC’s RO‑PERM troubleshooting guide makes this clear. If your system cannot shut off and runs continuously all day, stages one through three, the sediment and carbon pre‑filters, are constantly exposed to fresh incoming water. Instead of filtering only the ten or twenty gallons per day associated with occasional drinking water use, they may be processing hundreds of gallons per day of water that ultimately goes straight to the sewer. Over a period as short as one or two months, this continuous loading can deplete those filters and reduce their ability to protect the membrane from sediment and chlorine. That, in turn, shortens membrane life and increases the risk of both poor water quality and further mechanical failures.

The maintenance intervals recommended by manufacturers assume a normally cycling system. NU Aqua suggests replacing pre‑filters about every six months under typical use. APEC recommends at least every twelve months and stresses that forgetting to change pre‑filters on time can damage the automatic shut‑off valve and the membrane. Axeon’s industrial guidance aims for six to twelve months on pre‑filters and roughly two years on membranes; a forum contributor running a home system reported changing membranes every three to four years when rejection fell below about seventy‑five percent. If your drain runs nonstop, those intervals are no longer realistic.

The water and sewer implications are straightforward. Returning to the earlier example, if you drink about two gallons of RO water per day and your system wastes about ten gallons for every gallon produced, you could be sending more than 7,000 gallons of potable water to the sewer each year. Even at a five‑to‑one ratio, you are discarding roughly 3,600 gallons. Beyond the direct cost on your water bill, that is water your municipal utility must treat again.

At scale, concentrate and reject streams pose much bigger challenges. An analysis published in an American Chemical Society environmental journal examined RO concentrate from potable reuse facilities and found that trace pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and metals can concentrate to levels that pose chronic toxicity risks for aquatic life if discharged without further treatment. The study noted copper levels in RO concentrates from several plants in the range of a few to several tens of micrograms per liter, sometimes above US EPA chronic toxicity criteria for saltwater.

Valley Water, a California water agency, points out that the reverse osmosis concentrate generated in advanced treatment trains for direct potable reuse can hold contaminants at roughly six times the levels seen in typical treated wastewater. Because some estuarine environments have limited dilution, this concentrate cannot simply be blended and discharged without careful management.

Industrial studies reported in peer‑reviewed journals show that brines from high‑recovery RO systems can have very high hardness and scaling potential. One nanofiltration study documented that pretreating brackish‑water RO brine with nanofiltration removed more than eighty percent of total dissolved solids and over ninety percent of hardness, turning a high‑scaling stream into a much more manageable feed for a second RO stage. The brine from that nanofiltration step, enriched in calcium and magnesium, can even be reused for remineralizing soft desalinated water or recovering phosphate minerals.

Brine management consultancies such as Samco Technologies and YASA ET emphasize that RO brine is not just salty water. It accumulates silica, heavy metals, hardness, organics, and nutrients and can cause scaling, corrosion, and environmental harm if reused or discharged without control. Options such as zero liquid discharge schemes and nature‑based solutions like those being investigated by Valley Water trade higher capital and energy use for reduced long‑term environmental footprint.

For a homeowner, you are not managing a brine lagoon. But continuous wastewater discharge from your under‑sink system still means more water pumped, more energy used by treatment plants, more chemicals consumed in centralized treatment, and faster wear on your own equipment.

Reducing Wastewater Without Sacrificing Water Quality

The good news is that you can address continuous wastewater discharge on two fronts: fixing malfunctions and choosing or configuring more efficient systems.

On the repair side, the priority is clear. If your RO drain runs hours after you last used water, use the simulated full‑tank test and basic diagnostics described earlier to confirm the issue. Replace defective check valves, ASO valves, or permeate pumps promptly, and do not ignore a failing storage tank. Accept that long periods of continuous running will have prematurely aged your pre‑filters and possibly your membrane; bringing your maintenance up to date is part of the cure.

On the design side, several levers have been highlighted by manufacturers and researchers. Frizzlife emphasizes the value of high‑quality thin film composite membranes with around ninety‑nine percent total dissolved solids rejection. Compared with older membranes in the ninety‑five percent range, these higher‑performance elements can reduce wastewater by roughly ten to fifteen percent when paired with appropriate system design. Frizzlife also notes that, in some applications, allowing a slightly higher salt passage can modestly increase recovery, trading a small change in purity for five to seven percent more water harvested. For drinking water, this must always be balanced against your contaminant targets.

Pressure optimization is another tool. Residential RO units generally have an optimal pressure window somewhere between about forty‑five and eighty psi, as seen in NU Aqua’s system specifications and Frizzlife’s recommendations. Within the manufacturer’s rated range, increasing inlet pressure improves the driving force for osmosis and can reduce the fraction of water sent to drain. Frizzlife estimates that every additional five psi within that window can save an extra five to seven percent of water from becoming waste. Below the minimum, systems waste more water and may never shut off correctly. Above the maximum, you risk damaging membranes and housings.

The US EPA’s WaterSense specification offers a powerful shortcut when you are shopping for a new unit rather than optimizing an old one. A WaterSense‑labeled point‑of‑use RO system must be independently certified both for contaminant reduction performance and for efficiency, using no more than about 2.3 gallons of drain water for each gallon of treated water produced. The EPA estimates that if every under‑sink RO sold in the United States met this specification, the country would save more than 3.1 billion gallons of water each year, equivalent to the annual household water needs of nearly forty‑one thousand American homes. For many households, simply choosing a WaterSense‑qualified system when it is time to replace an older unit is the single easiest way to cut waste.

Frizzlife and other efficiency‑focused manufacturers also point to non‑potable reuse opportunities for the reject stream. Because RO concentrate from a household system is typically just tap water with higher mineral content and whatever contaminants your tap water already had, some households route this water to tasks such as garden irrigation, car washing, or floor cleaning, capturing a portion of what would otherwise be lost. With careful plumbing design and clear labeling to avoid accidental drinking, they estimate that around thirty percent of the reject stream can sometimes be repurposed in this way. Whether this is practical or allowed depends heavily on local plumbing codes and site conditions, so always consult a professional before attempting it.

At the industrial and municipal scale, the playbook is broader. Studies in the scientific literature and guidance from companies such as Samco highlight several strategies: nanofiltration pretreatment to reduce scaling potential, multi‑stage RO with high recovery, energy‑recovery devices, advanced oxidation and adsorption for concentrate polishing, and zero liquid discharge systems that evaporate the remaining brine and recover solids. Water agencies like Valley Water are investigating nature‑based solutions that use restored wetlands or engineered habitats to attenuate contaminants in RO concentrate while providing ecological co‑benefits. Although these approaches are beyond the scope of a kitchen‑sink system, they underscore a shared principle: treat wastewater streams as resources to manage, not just nuisances to ignore.

To put the impact of equipment choice into perspective, consider the following illustration for a household that uses about two gallons of RO water per day.

RO system type |

Approximate wastewater per gallon of RO water |

Approximate yearly wastewater at 2 gallons per day |

Notes |

Very inefficient under‑sink RO |

10 gallons |

about 7,300 gallons |

Similar to worst‑case units highlighted by WaterSense |

Typical older point‑of‑use RO |

5 gallons |

about 3,650 gallons |

Within the “five or more gallons” range cited by WaterSense |

Efficient modern RO, roughly two‑to‑one |

2 gallons |

about 1,460 gallons |

In line with Frizzlife’s description of many systems |

WaterSense‑labeled RO (maximum allowed) |

2.3 gallons |

about 1,700 gallons |

Based on the WaterSense efficiency specification |

These are approximate values, but they show how tackling both continuous discharge faults and underlying efficiency can dramatically lower the amount of treated water you lose each year.

FAQ: Continuous Wastewater Discharge And Your RO

Is continuous wastewater discharge dangerous to my family’s health?

In most homes, the immediate health risk from continuous RO drainage is low, because the waste stream goes directly into your sink’s drain and then into the normal sewer or septic system. The bigger concern for health is what the problem implies: if your system’s valves, pressure, or membrane are not behaving as designed, you cannot be confident it is consistently removing contaminants. As several sources emphasize, including Puretec Water and the US EPA, RO membranes are only part of the treatment train. They rely on pre‑filters, correct pressure, intact components, and regular maintenance to meet their performance claims. Treat continuous drainage as a sign that the system needs attention, not as a direct exposure pathway.

Can I just ignore a slow trickle from the drain if my RO water tastes fine?

Taste is a poor indicator of safety or efficiency. Many dissolved contaminants that RO is designed to remove, including nitrates, PFAS, and some heavy metals, have little or no taste. At the same time, a slow but continuous trickle can still waste hundreds or thousands of gallons per year and deplete your filters. APEC cautions that non‑stop operation over one to two months likely exhausts the pre‑filters, leaving the membrane exposed. Even if your water tastes fine, you are probably wearing out the system prematurely and paying for water you never drink.

When should I call a professional instead of troubleshooting myself?

Any time you are uncomfortable working under the sink, dealing with pressurized lines, or interpreting test results, it is wise to call a qualified water treatment technician. Professional help is especially appropriate if the basic tests described earlier do not clearly identify the problem, if your system feeds multiple outputs and you suspect hidden leaks, or if the unit is built into a more complex treatment stack with softeners, UV, or whole‑house filtration. NU Aqua Systems and other manufacturers openly encourage homeowners to seek expert support when recurring issues or complicated installations are involved, not only to protect equipment but to ensure long‑term drinking water quality.

As a water wellness advocate, I want your RO system to do three things at once: deliver reliably clean water to your glass, respect your utility bill, and minimize its footprint on the watershed you live in. Understanding when wastewater discharge is normal, when it signals trouble, and how design choices affect both is a powerful step toward smarter hydration at home.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/128347989/Basics_of_Reverse_Osmosis

- https://www.epa.gov/watersense/point-use-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8002872/

- https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/water_issues/programs/ocean/desalination/docs/dpr051812.pdf

- https://www.usbr.gov/lc/phoenix/programs/cass/pdf/SABD.pdf

- https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/context/water_rep/article/1504/viewcontent/Reverse_20Osmosis_20in_20the_20Treatment_20of_20Drinking_20Water.pdf

- https://do-server1.sfs.uwm.edu/visit/N59418026T/pub/N86896T/reverse-osmosis__manual__operation.pdf

- https://www.valleywater.org/accordion/reverse-osmosis-concentrate-management

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsenvironau.1c00013

- https://www.ecosoft.com/post/most-common-problems-with-reverse-osmosis-systems

Share:

Understanding Sudden Increases in TDS Levels for Water Quality Management

Should People with Gastroesophageal Reflux Drink Alkaline Water?