Slow, hesitant water flow during the rinse or flush phase of a reverse osmosis (RO) system is one of the most common complaints I hear from homeowners and facility managers. As a Smart Hydration Specialist, I see it not just as an annoyance at the faucet but as an important early signal about membrane health, pretreatment quality, and overall water wellness.

In this article, we will unpack what a “slow rinse rate” really means, why it happens, how to diagnose it, and how to prevent it in both home and light commercial RO systems. The goal is to help you protect your membrane, keep your flow strong, and stay confidently hydrated with high‑quality water.

What “Rinse Rate” Really Means in an RO System

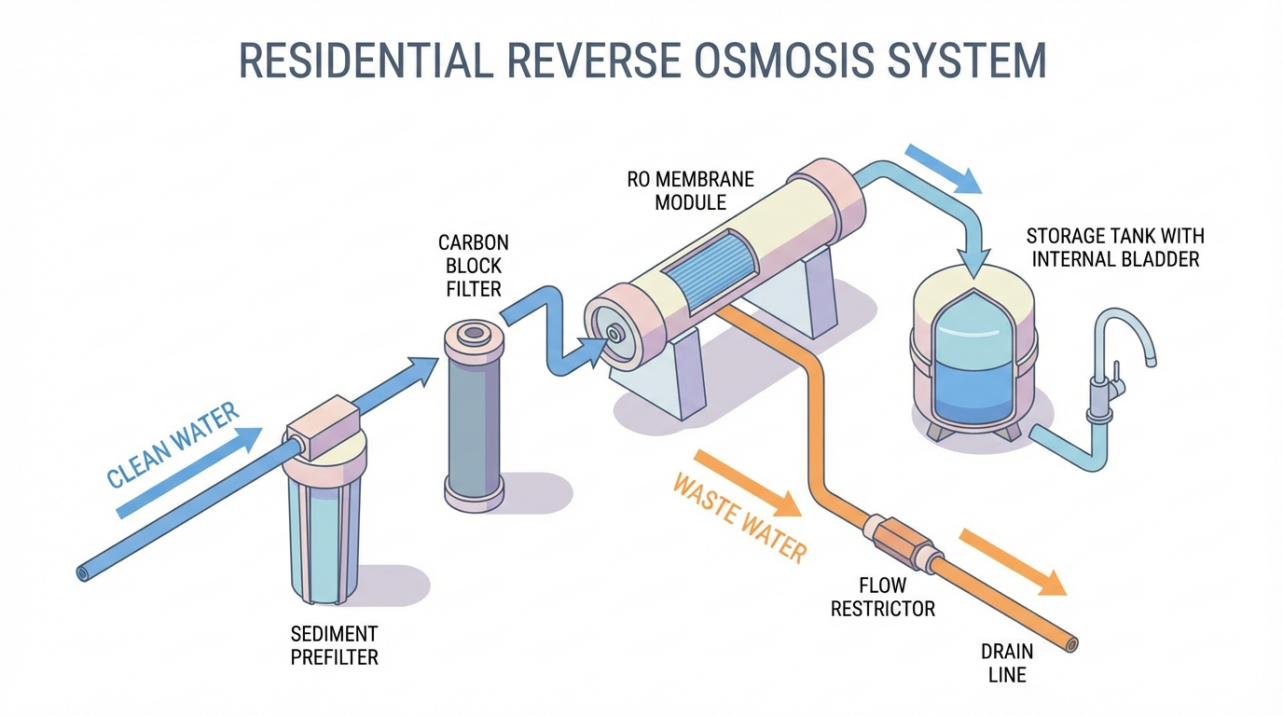

When you open your RO faucet after the system has been idle, there are two phases that most people lump together as “flow.”

First, you get water pushed out by the storage tank. This is the immediate, pressurized stream you feel when the tank is partly full. Second, once the tank empties or is bypassed, you see the true production or rinse rate of the membrane. That slower, steady trickle is the rate at which your RO membrane is actually producing water and flushing concentrated brine to the drain.

Manufacturers and service guides from brands like ESP Water, Glacier Fresh, and Nelson Water describe this membrane production in gallons per day (GPD). A typical under‑sink drinking water RO system is often rated around 50–75 gallons per day, which works out to only a few ounces per minute when the tank is empty. That slow, continuous drip or light stream is normal.

The problem begins when even that expected slow rinse becomes noticeably slower over time, or when your system never seems to refill the tank the way it used to. At that point, a slow rinse rate is not just a convenience issue; it is a performance and maintenance signal.

Why Slow Rinse Rates Matter For Water Wellness

A reduced rinse rate is more than a patience tester when you fill a bottle. It is closely tied to water quality, membrane health, and long‑term safety.

Technical briefs from Ecosoft and Axeon Water point out a simple rule: when RO flow slows, it is usually because something is restricting the path of the water. That “something” is often clogged prefilters, a fouled or scaled membrane, low pressure, or a pressurized storage tank that is not behaving correctly.

Clogged filters and fouled membranes do not just slow water; they also reduce contaminant removal performance. Ecosoft notes that the same issues behind slow flow often show up as higher total dissolved solids (TDS), off‑tastes, or odors in the water. If your RO system is taking much longer to rinse or refill and your water no longer tastes as crisp as it used to, that combination is a red flag.

In my field work, the households that ignore slow rinse rates tend to be the ones that later discover serious scaling on the membrane, a ruptured storage tank bladder, or chronic biofouling that forces expensive replacements. Addressing a slow rinse rate early is one of the simplest ways to extend membrane life and maintain consistently high‑quality drinking water.

The Science Behind Slow Rinse: Membranes, Fouling, and Pressure

Slow rinse rates almost always trace back to a handful of physical realities inside the RO system. Understanding them will make the troubleshooting steps later feel much more logical.

Membrane fouling and scaling

The RO membrane is a thin, semi‑permeable film that lets water molecules pass while rejecting salts, metals, and other contaminants. Over time, contaminants accumulate on this surface. Multiple sources, including AquaComponents, Chunku Water Treatment, and Vontron, describe several common foulants.

Mineral scaling is one major cause. When calcium, magnesium, sulfate, and silica concentrations rise in the concentrate stream, they can exceed their solubility limits and precipitate onto the membrane as hard scale. AquaComponents lists calcium carbonate and calcium sulfate as especially problematic. These deposits narrow the flow channels and block membrane pores, which directly reduces water permeability. Even a thin layer can cut flow significantly.

Biofouling is another. Xylem describes biofouling as the buildup of bacteria and organic matter on membrane surfaces. This slimy layer increases resistance, adds to pressure drop, and can be very difficult to remove once established. It often comes from inadequate pretreatment or long periods of stagnation.

Colloidal and particulate fouling, such as fine clay, iron hydroxides, or diatoms in seawater, also contribute. These particles lodge in feed spacers and channels, restricting crossflow and increasing differential pressure. Chunku Water Treatment and Vontron both note that when normalized permeate flow has declined by about 10–15% or differential pressure has risen by a similar amount, chemical cleaning becomes necessary.

All of these phenomena share one effect that you can feel: they choke the membrane and slow the rinse.

Pressure and hydraulic imbalances

RO is a pressure‑driven process. If feed pressure is too low, even a perfectly clean membrane will produce less water. Consumer‑facing guidance from ESP Water, Glacier Fresh, and Nelson Water consistently states that most under‑sink RO systems need at least about 40 psi of inlet pressure, with around 60 psi preferred, to produce water at their rated capacity.

If your municipal or well pressure drops below that range, the rinse rate will fall. In some cases, a booster pump is required to bring pressure into the optimal zone.

Inside the system, pressure is also shaped by the flow restrictor. As explained by Fresh Water Systems, the restrictor on the drain line keeps back pressure on the membrane high enough to drive water through while limiting wastewater. If the restrictor becomes clogged or mismatched to the membrane size, it can either over‑restrict flow, causing very slow rinse and potential scaling, or under‑restrict it, wasting water and reducing permeate quality. Manufacturers commonly recommend replacing the flow restrictor whenever the membrane is replaced, roughly every two years in many systems.

Storage tank and bladder behavior

In pressurized RO systems, the storage tank has an internal air bladder that provides push to deliver water to your faucet. ESP Water and Nelson Water both advise that when the tank is completely empty, the air side should read about 7–8 psi. If tank pressure is much lower, the faucet stream becomes weak even if the membrane is producing water. If the bladder ruptures, you often see a strong flow for a very short time, followed by a rapid drop to a dribble; the tank can no longer maintain pressure.

From a rinse‑rate perspective, a mis‑pressurized or failed tank can mask what the membrane is doing. You may think the membrane is very slow when, in reality, the membrane is fine and the tank is the culprit.

How To Measure Your True Rinse Rate

Before you can decide whether your rinse rate is actually slow, you need a simple, objective way to measure it. ESP Water offers a practical method that works for most home RO systems:

First, turn the RO faucet fully on and leave it open. Let the tank drain until only a steady drip or very slow continuous flow remains. This is the membrane’s true production rate.

Next, place a measuring cup under the faucet and collect water for exactly 60 seconds, counting how many fluid ounces you obtain in one minute.

Finally, convert that number to an approximate daily production rate. ESP Water uses a straightforward calculation: multiply the ounces per minute by 1,440 (the number of minutes in a day) and then divide by 128, since there are 128 ounces in a gallon. For instance, if you measure 4 ounces in one minute, 4 times 1,440 is 5,760. Dividing that by 128 gives about 45 gallons per day, which matches the example in their guide.

This quick test lets you compare your real‑world rinse rate to your system’s rated gallons per day. Many popular home systems are sold around 50 or 75 GPD, and their product pages from ESP Water and similar suppliers confirm those numbers. If your measured production is close to the rating, your slow faucet experience may simply reflect the fact that RO is a gradual process. If your measured rate is much lower than it used to be or far below the system rating, then you truly have a slow rinse problem to solve.

Common Root Causes of Slow Rinse Rates

When I troubleshoot slow‑flow complaints, I start with a simple mental checklist. Industry articles and service bulletins from Axeon Supply, ESP Water, Glacier Fresh, Nelson Water, Ecosoft, and others line up remarkably well with what I see in the field.

Clogged prefilters and carbon cartridges

Sediment and carbon block filters are designed to catch particulates and chlorine before they reach your membrane. They gradually fill with debris and become more resistant to flow. Glacier Fresh and Nelson Water both identify clogged prefilters as one of the most common reasons for slow RO output.

Consumer maintenance guides from multiple brands recommend replacing pre‑ and post‑filters every 6–12 months, with more frequent changes, sometimes every 6 months, in areas with poor feed water quality. When those filters are left in place for several years, it is almost guaranteed that your rinse rate will suffer and your membrane will be under more stress than necessary.

Fouled or scaled membrane

If prefilters are neglected or feedwater carries a heavy load of minerals or organics, the RO membrane itself eventually fouls. Crystal Quest, Ion Exchange, and Axeon Water all note that most RO membranes in properly maintained systems last roughly 2–5 years. In harder or heavily contaminated feedwater, the lifespan can be shorter, and regular cleaning becomes important.

Technical documents from AquaComponents, Vontron, and Chunku Water Treatment converge on similar rules of thumb. After normalizing for temperature and pressure, if permeate flow has dropped by about 10–15% or if the pressure difference across the membrane has increased by about 10–15% compared with its clean baseline, it is a sign that fouling or scaling is significant enough to warrant chemical cleaning. If cleaning fails to restore performance and the decline is large, replacement is often more economical.

In practice, this means that if your measured rinse rate today is only around three‑quarters of what it was when the system was new, and your prefilters are not the obvious issue, the membrane is likely the bottleneck.

Low inlet water pressure

Residential troubleshooting guides from ESP Water, Glacier Fresh, Nelson Water, and Ecosoft all stress the importance of feed pressure. When the pressure entering the RO unit falls below about 40 psi, production slows dramatically. Around 60 psi, most standard under‑sink systems approach their design performance.

Low pressure can be temporary, such as a municipal issue that affects all taps in your home, or persistent, such as a long plumbing run, undersized piping, or pressure losses from other fixtures. If you have chronically low pressure, installing a booster pump designed for RO systems is a common solution recommended by both residential suppliers and industrial providers like Axeon Water.

Storage tank issues

Support articles from ESP Water and Nelson Water describe two distinct tank‑related patterns. When the tank’s air charge is low but the bladder is intact, you see weak flow that quickly falls off as soon as you draw water, even though the membrane may be producing at a normal rate. Checking and adjusting tank pressure takes only a tire‑type gauge and a small pump: with the tank completely empty of water, the air side should be set around 7–8 psi.

When the bladder is ruptured, the pattern is more pronounced. You may get normal flow for a small volume, such as about one cup of water, and then the stream collapses to a trickle. In that case, the only reliable fix is to replace the storage tank, because the bladder itself cannot be repaired.

Flow restrictor and tubing problems

Fresh Water Systems provides a detailed explanation of the flow restrictor’s role. If it becomes clogged with scale or debris, it can over‑restrict the waste line and raise concentrate pressure too much. This increases the burden on the membrane, accelerates scaling, and slows permeate flow. If the restrictor is damaged or oversized, it can allow too much wastewater, reducing pressure at the membrane surface and cutting permeate production. Signs include an unusual amount of water going to drain or erratic flow at the faucet.

Blocked or kinked tubing within the system can have similar effects. Glacier Fresh notes that squeezed, kinked, or partially crushed tubing sections can create hidden bottlenecks. Straightening the lines and re‑seating fittings often resolves mysterious slow‑flow issues with no parts replacement.

A Quick Symptom–Cause Snapshot

The table below summarizes how some of these issues present at the faucet and in the system, based on consumer guides from ESP Water, Glacier Fresh, Nelson Water, Ecosoft, and Fresh Water Systems.

What you notice at the faucet or system |

Likely underlying cause |

Typical confirmation step |

Strong flow for a few seconds, then an abrupt drop to a weak trickle |

Ruptured storage tank bladder |

Tank feels heavy even when “empty,” air pressure reading is abnormal, and tank replacement restores normal behavior |

Consistently weak flow that never feels pressurized, even after long idle periods |

Low tank air pressure or very clogged prefilters |

Tank air side reads below about 7–8 psi when empty, or filters are visibly old and replacing them restores flow |

Rinse rate (measured ounces per minute) far below system rating, even with new filters |

Fouled or scaled RO membrane |

Performance charts show a flow decline of about 10–15% or more since new, and cleaning or membrane replacement is needed |

Slow flow at all faucets in the home, including the RO system |

Low municipal or well pressure |

Pressure gauge on main line shows low readings; flow improves when pressure issue is corrected or a booster pump is installed |

Unusual amount of water going to drain or very noisy drain line along with slow permeate flow |

Faulty or clogged flow restrictor |

Inspecting and replacing the restrictor with the correct size restores normal waste‑to‑permeate ratio and flow |

Sudden slow flow after moving the system or doing plumbing work |

Kinked or partially crushed tubing |

Visual inspection reveals tight bends or pinched lines; correcting them improves flow |

When Slow Rinse Rates Mean It Is Time To Clean

Once you have ruled out basic pressure, tank, and filter issues, slow rinse rates are often your membrane’s way of asking for a cleaning.

Industrial and commercial references from Vontron, Chunku Water Treatment, Crystal Quest, and Axeon Water all converge on the same principles, even though they target larger systems than a typical kitchen RO.

First, preventive cleaning is more effective than waiting for severe fouling. Vontron recommends chemical cleaning roughly every six months in long‑running systems to prevent pollutants from building up excessively on the membrane surface. Crystal Quest similarly suggests cleaning every 6–12 months or whenever performance declines, noting that older or heavily fouled membranes may be better replaced than repeatedly cleaned.

Second, standardized performance data should drive the decision. When water production drops by more than about 15% from the initial value, when salt passage increases by more than about 10%, or when the pressure difference between feed and concentrate rises by more than about 15%, Vontron advises performing chemical cleaning promptly. Chunku Water Treatment and Axeon Water echo the idea that waiting until declines exceed roughly that 10–15% band makes it harder to recover original performance.

The essence for a homeowner is simple. If your rinse test shows a meaningful decline compared with your own baseline and the system is more than a year or two old, and especially if filter changes and pressure checks do not restore flow, your membrane is likely due for cleaning or replacement. For small residential units, many homeowners skip chemical cleaning entirely and simply replace the membrane in the two to four year window, which aligns with the lifespan ranges mentioned by Ion Exchange and Crystal Quest.

How Membrane Cleaning Affects Rinse Rates

If you have a larger residential, commercial, or light industrial system, you may actually perform membrane cleaning rather than immediate replacement. In that case, understanding how cleaning ties into rinse rate will help you evaluate whether the cleaning worked.

Crystal Quest and Vontron describe two main cleaning styles. In lighter fouling for smaller systems, a removal‑and‑soak method is often used, where the membrane is taken out and soaked for 30–60 minutes in a high‑pH cleaner for organic fouling or a low‑pH cleaner for mineral scale, usually mixed at about 1 pound of cleaner per 10 gallons of solution. For heavier fouling and larger systems, a clean‑in‑place (CIP) system circulates cleaning solution through the membranes at controlled flow, pressure, and temperature without disassembly.

Both sources emphasize that temperature has a strong influence on cleaning effectiveness. Crystallized foulants loosen more readily at moderately warm temperatures. Vontron recommends cleaning solutions around 77–86°F for many elements, with flushing water at temperatures roughly above 68°F. Crystal Quest similarly recommends keeping cleaning solutions at or below about 86°F while respecting membrane temperature limits specified by the manufacturer.

After cleaning, both recommend thorough rinsing with RO permeate until residual chemicals are completely flushed out. At that point, measuring your rinse rate again gives an objective way to judge cleaning success. If normalized permeate flow and rinse rate recover close to original values, your cleaning was effective. If performance remains significantly depressed, the foulant may be irreversible or the membrane may have aged beyond economical recovery.

On the industrial side, researchers cited on ScienceDirect have even begun using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to monitor cleaning in real time. Their work shows that as the fouling layer’s electrical resistance decreases during cleaning, permeate performance improves. While that is not something you will use in a home kitchen, it underscores the same principle: slow rinse rates reflect real physical resistance at the membrane surface, and effective cleaning should measurably relieve that resistance.

Preventing Slow Rinse Rates: Maintenance and Design

The most cost‑effective way to deal with slow rinse rates is to avoid them as much as possible. Industry best practices from Ion Exchange, Axeon Water, Xylem, AquaComponents, and Nelson Water point to a few preventive themes.

Regular filter changes and system hygiene matter. Keeping to a 6–12 month schedule for pre‑ and post‑filters, as recommended by Crystal Quest, Glacier Fresh, and Nelson Water, prevents particulate overload and protects the membrane. Flushing the system according to the manufacturer’s start‑up and shutdown procedures helps limit stagnation and biofilm growth.

Maintaining proper pressure protects both flow and membrane life. Checking inlet pressure and tank air pressure a few times a year, especially if your flow pattern changes, keeps your system operating where it was designed. If your home supply pressure hovers below about 40 psi, discussing a dedicated RO booster pump with your water treatment professional is often wise.

Pretreatment is critical in challenging water. Xylem emphasizes that in seawater and other difficult feed sources, pretreatment must be tailored to the water’s suspended solids and organic content. They highlight the Silt Density Index (SDI) as a global measure of fouling tendency and note that most RO membranes need feedwater with SDI below about 3.0. AquaComponents and Axeon Water likewise stress that good pretreatment, including sediment filtration, carbon, possible water softening, and antiscalant dosing, dramatically lowers scaling and fouling rates. In homes with very hard water, Nelson Water recommends adding a water softener upstream of the RO to reduce scale on the membrane.

Right‑sizing replacement and cleaning intervals keeps flow performance predictable. Ion Exchange notes that RO membranes commonly last around 2–5 years when properly maintained. Vontron and Crystal Quest recommend chemical cleaning whenever normalized performance declines by 10–15% and preventive cleaning about every six months in continuous systems. Tracking your own rinse rate over time, even just a few times per year, will give you a personal performance baseline and make it obvious when it is time to act.

Health and Hydration Implications

From a hydration perspective, the main risk of a slow rinse rate is not that the water becomes unsafe overnight, but that performance issues behind the slow flow can eventually compromise purification.

Ecosoft points out that the same mechanical issues that reduce flow, such as clogged filters or exhausted membranes, are also the ones that allow more contaminants to slip through. Rising TDS readings, off‑flavors, or odors together with slow rinse are early warnings that your hydration water is no longer as clean as intended.

On the positive side, regular maintenance that keeps rinse rates healthy often improves taste and encourages better hydration habits. Families frequently tell me that once their system is flowing properly again and water tastes crisp and fresh, they naturally drink more and rely less on sugary beverages or single‑use bottled water.

If you use your RO water for baby formula, medical devices like CPAP humidifiers, or for family members with sensitive immune systems, paying attention to rinsing performance and maintenance schedules is especially important. When in doubt, combining a rinse‑rate check with a simple TDS test or professional water analysis gives peace of mind.

FAQ: Slow Rinse Rates in RO Membrane Systems

Is a slow rinse rate dangerous for my health?

A mildly slow rinse rate by itself is not automatically a health hazard, but it is a symptom that should not be ignored. Industry guidance from Ecosoft and Axeon Water shows that flow decline goes hand in hand with clogging and membrane fouling. Those conditions can eventually reduce contaminant rejection. If your water still tastes normal and your TDS readings are consistent, you likely have some time to troubleshoot. If slow rinse is accompanied by bad taste, odor, or rising TDS, you should treat it as urgent and service the system promptly.

How do I know if I should clean the membrane or just replace it?

Industrial recommendations from Vontron, Crystal Quest, and Chunku Water Treatment suggest cleaning when normalized permeate flow or pressure drop has shifted by roughly 10–15% from the clean baseline. In larger systems, that is often economical, and detailed cleaning procedures are used. In typical home systems, by the time performance has clearly declined and the membrane is a few years old, many homeowners choose replacement instead. If your system is under two years old and you know the membrane has been exposed to unusual fouling, a professional cleaning might be worthwhile. If it is three to five years old and performance is poor, replacement is usually the simpler and more reliable option.

When should I call a professional instead of troubleshooting myself?

You can safely handle many basic checks yourself, including measuring rinse rate, changing prefilters, checking tank pressure, and looking for kinked tubing. You should consider calling a professional if you suspect a ruptured tank bladder, need a booster pump installed, are dealing with chronically hard or contaminated feedwater, or if slow rinse persists after you have replaced filters and verified pressure. Technical providers like Nelson Water and ESP Water emphasize that professional diagnostics can catch issues like hidden flow restrictor problems, complex fouling, or installation errors that are hard to spot without experience.

Keeping rinse rates healthy is one of the most practical ways to protect your RO membrane, your investment, and your everyday hydration. By combining a simple rinse‑rate measurement with scheduled maintenance and informed troubleshooting, you can enjoy confident, consistent flow of clean water from your RO system for years at a time.

References

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/articles/reverse-osmosis-optimization

- https://chunkewatertreatment.com/ro-membrane-cleaning-techniques/

- https://complete-water.com/video/reverse-osmosis-low-flow-or-low-permeate-after-cleaning

- https://www.ecosoft.com/post/most-common-problems-with-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/why-reverse-osmosis-water-flow-is-slow?srsltid=AfmBOoopSGU7n7dhOBGmkvfV2IbPNbkL5Iqu_Mt3D_e7f89kV29wtVt8

- https://pt.ionexchangeglobal.com/maintaining-your-reverse-osmosis-membrane/

- https://www.justanswer.com/plumbing/hu61g-reverse-osmosis-system-not-allowing-water.html

- https://en.vontron.com/Investor_details/50.html

- https://axeonsupply.com/blogs/news/troubleshooting-common-issues-in-reverse-osmosis-systems?srsltid=AfmBOori3K4vpZOPiXse5Kr7EDY8zikAR4CFJay8lFr6V6k27_QYye-F

- https://www.axeonwater.com/blog/best-practices-for-operating-and-maintaining-reverse-osmosis-systems/

Share:

Emergency Repair Techniques for Broken Filter Clips in Appliances

Identifying Water Stains at Joints: Leakage or Condensation?