As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time explaining one surprisingly tricky idea to homeowners: a reverse osmosis membrane is excellent at removing many dissolved solids and contaminants, but it behaves very differently with dissolved gases. That difference affects everything from the smell of your water to its pH, taste, and even how your plumbing ages over time.

This article walks through how reverse osmosis (RO) membranes actually work, what they remove well, where they struggle with gases, and how to choose and operate a system that truly supports healthy, great‑tasting water at home. The explanations draw on university extension guidance, engineering references, and public‑health sources such as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, alongside what I see every day in real kitchens and utility rooms.

Reverse Osmosis in Plain Language

From Osmosis to Reverse Osmosis

Osmosis is a natural process you probably first heard about in high school biology. In osmosis, water moves through a semi‑permeable membrane from a weaker solution toward a stronger solution until the concentrations balance. Plants use this to pull water into their roots, and your kidneys use similar processes to manage fluid balance.

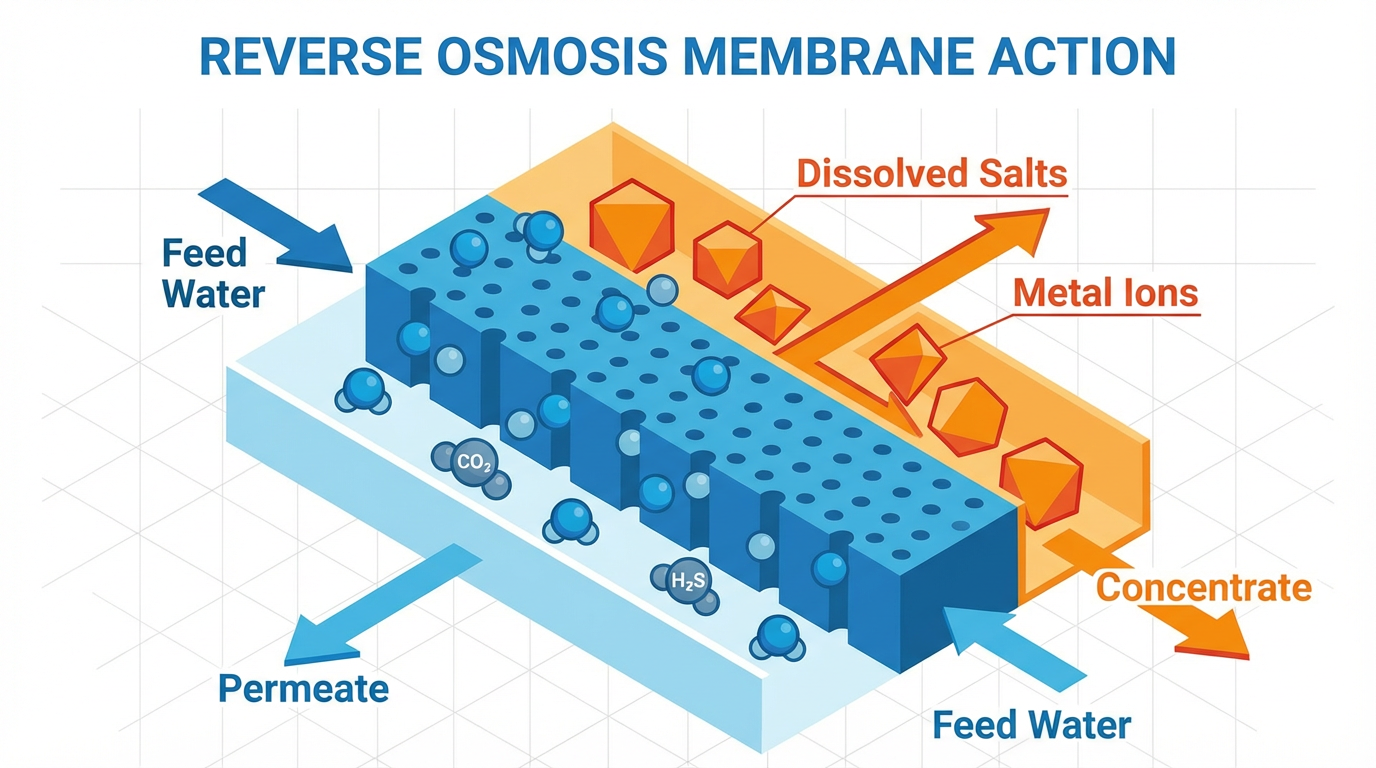

Reverse osmosis turns that natural flow around. Instead of letting water drift from low to high concentration, an RO system uses pressure to push water from the more concentrated, contaminated side of a membrane toward the purer side. The membrane allows water molecules to pass while holding back most dissolved salts, metals, and many other substances.

In typical drinking‑water applications, this process uses household water pressure or a small pump. Engineering references describe RO as a form of “hyperfiltration” because it separates at the molecular scale rather than just straining out particles.

How an RO Membrane Works

An RO membrane is not a simple screen with visible holes. It is a very thin, dense polymer layer supported by several backing layers. Most modern residential and many commercial elements use thin‑film composite (TFC) polyamide membranes wound into a spiral configuration. That spiral‑wound design, used by major manufacturers, packs a large membrane area into a compact housing and simplifies plumbing and maintenance.

At the membrane surface, water molecules diffuse through the polymer structure, while ions and larger molecules are largely rejected. Typical drinking‑water RO membranes are designed to remove roughly 95 to 99 percent of dissolved salts under the right conditions. They also reduce many metals, such as lead and arsenic, and significantly lower total dissolved solids (TDS), which is what a home TDS meter is measuring.

To keep membranes from clogging or degrading, a complete system adds several stages, such as sediment filters and activated carbon filters before the membrane, and sometimes polishing or remineralization stages afterward. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency describes this type of setup as a point‑of‑use system when it serves a single faucet, usually under the kitchen sink.

Performance Metrics You Will Hear About

When you talk to water professionals or look at spec sheets, several performance terms come up repeatedly, and they are worth understanding in everyday language.

Rejection rate describes how much of a particular contaminant the membrane removes. For example, university extension materials show that if a membrane rejects 85 percent of nitrate, incoming water at 40 milligrams per liter of nitrate could be reduced to around 6 milligrams per liter, which meets the federal health standard, while the same membrane would leave water with 80 milligrams per liter of nitrate still above the standard. This illustrates why matching membrane performance to your specific contaminants matters.

Recovery rate describes how much of the incoming water becomes treated water. A typical household RO system may be designed for about 20 to 30 percent recovery. If 100 gallons per day enter the unit and the recovery is 20 percent, about 20 gallons per day become treated water and about 80 gallons per day go to the drain as concentrate.

Flux is the rate of water passing through the membrane per unit area, often given in gallons per square foot per day. Flux, recovery, and rejection all influence how large a system you need, how efficiently it uses water, and how often you will need to maintain it.

Temperature and pressure also matter. Extension data show that RO production drops roughly 1 to 2 percent for every degree Fahrenheit below about 77°F. In a region where groundwater is closer to 45°F, that can mean only about half as much treated water as the same system would produce with warmer water. Adequate feed pressure is also critical: higher pressure differences generally increase both contaminant rejection and recovery.

Types of RO Membranes and What They Remove

Membrane Materials and Configurations

There are two main membrane families you will see discussed for drinking water: cellulose‑based membranes and thin‑film composite membranes.

Cellulose triacetate (CTA) membranes tolerate chlorine in the feed water, which helps control microbial growth, but they typically provide slightly lower contaminant rejection, often in the range of about 85 to 95 percent for many dissolved salts. They are used in some applications where a small amount of chlorine is desirable upstream.

Thin‑film composite (TFC) membranes generally deliver higher rejection, often around 95 to 98 percent or more, and are the workhorse of modern residential and many commercial systems. However, they are sensitive to oxidants like free chlorine, which can damage the polymer. That is why most TFC‑based systems include a carbon prefilter to remove chlorine and protect the membrane.

In spiral‑wound elements, multiple sheets of membrane and spacer material are wrapped around a central tube. This configuration, used by manufacturers such as DuPont, helps lower replacement costs compared with some older module types and offers engineers more design flexibility.

What RO Removes Well

Across university, industry, and public‑health sources, several contaminant categories consistently show up as strengths for RO.

RO membranes are particularly effective at removing dissolved salts and minerals that contribute to high TDS, such as sodium, chloride, calcium, magnesium, and many others. In practical terms, this is why RO is the dominant technology for seawater desalination and treatment of brackish groundwater.

They also reduce many metals, including lead, arsenic, chromium, copper, and others listed by manufacturers and health agencies. Properly designed systems can bring certain metals down below regulatory limits, especially when combined with appropriate pretreatment.

Microbiological contaminants are also significantly reduced. RO membranes can block many bacteria and protozoan cysts such as Cryptosporidium, and, when used with prefilters and disinfection, form part of systems that remove or inactivate a wide range of microbes. Materials from water‑treatment providers and public‑health agencies consistently note the ability of RO to reduce bacteria and some viruses under controlled conditions.

RO also lowers many inorganic contaminants of health concern, such as nitrate and fluoride, and can reduce certain radionuclides like radium and uranium when present, as described in extension guidance.

The table below summarizes how home RO generally performs for common contaminant groups, based on the research notes.

Contaminant category |

How the RO membrane performs |

What this means at home |

Dissolved salts and minerals (TDS) |

Typically around 95–99 percent reduction when the system is properly designed and maintained |

Noticeably lower TDS readings, less salty or bitter taste, and often less scaling on kettles and appliances |

Heavy metals (lead, arsenic, chromium, etc.) |

High removal efficiency when membranes are in good condition |

An important line of defense where plumbing, wells, or local reports indicate metal concerns |

Nitrate and fluoride |

Significant reduction, though effectiveness depends on incoming levels and rejection rating |

Can help bring certain contaminants within health standards if the membrane’s rejection is high enough |

Microorganisms (bacteria, some viruses, protozoa) |

Membrane blocks many microbes; best used with disinfection and good pretreatment |

Added layer of safety, especially for private wells, but not a substitute for proper disinfection |

Many organic chemicals and pesticides |

Membrane plus activated carbon stages reduce many higher‑molecular‑weight organics |

Often improved taste and odor and lower levels of various industrial and agricultural residues |

What RO Does Not Remove Well

No single device handles everything, and RO has real limitations.

Research from university extension programs and engineering references highlight that RO does not effectively remove certain dissolved gases. Hydrogen sulfide, the gas responsible for “rotten egg” odors, is a prime example. Many volatile organic compounds and solvents also pass partially through the membrane because of their small size and chemical nature. That is why systems often include activated carbon filters before or after the membrane to capture substances that RO does not handle well.

RO also removes minerals indiscriminately. It does not distinguish between “good” minerals like calcium and magnesium and undesirable ones. Articles aimed at homeowners and guidance from organizations such as the World Health Organization point out that RO water tends to be low in minerals and may be slightly acidic, and that long‑term reliance on completely demineralized water is not ideal. At the same time, those sources note that most essential minerals typically come from food rather than water, which helps put the issue in context.

Gas Filtration Effects: The Often‑Overlooked Side of RO

Dissolved gases are central to how water smells, tastes, and behaves in plumbing, yet they are easily misunderstood because they interact with RO membranes very differently than dissolved salts or metals.

Dissolved Gases Versus Dissolved Solids

Dissolved solids such as sodium or calcium exist as ions in water and interact strongly with the charged, dense structure of an RO membrane. That interaction makes them relatively easy for the membrane to reject.

Dissolved gases such as carbon dioxide or hydrogen sulfide behave differently. They are small, uncharged molecules that can diffuse through membrane materials more readily. Engineering guidance on RO systems explicitly notes that RO membranes do not effectively remove dissolved gases like carbon dioxide.

Similarly, household treatment bulletins point out that hydrogen sulfide gas often passes through RO and requires other treatment methods.

This is why a glass of RO water can still have a noticeable smell if a dissolved gas is the source of the odor rather than a dissolved salt or metal.

Hydrogen Sulfide and the Rotten‑Egg Problem

Hydrogen sulfide is one of the most frustrating issues I see in well‑water homes. The classic rotten‑egg smell can appear in hot water, cold water, or both, depending on where it enters the system and how the plumbing is laid out.

University guidance on RO treatment is clear: RO does not effectively remove hydrogen sulfide. The gas is simply too small and too mobile at the molecular level. In practice, this means that installing a point‑of‑use RO unit under the sink may do an excellent job of lowering TDS and metals but still leave an objectionable odor.

To deal with hydrogen sulfide, additional treatment is usually needed. Common approaches include oxidizing the sulfide to a particle that can be filtered out, or using activated carbon and other specialized media designed for sulfur removal. Importantly, those treatments are typically placed before the RO membrane. If you rely on RO alone for a sulfur problem, you are likely to be disappointed.

Carbon Dioxide, pH, and “Acidic” RO Water

Carbon dioxide is even more subtle. Engineering texts explain that RO membranes do not effectively remove dissolved carbon dioxide. When that gas passes into the permeate and reacts with water, it forms carbonic acid, which can lower the pH slightly. Research notes describe typical RO permeate as low‑mineral water with slightly reduced pH compared with the incoming water.

Other sources focused on the pros and cons of RO report that RO water often has a pH in roughly the 6 to 7 range. That is mildly acidic on the pH scale. Because minerals that would otherwise buffer the water are removed, this low‑mineral, slightly acidic water can be more corrosive to certain metals in plumbing and fixtures.

In the home, that can show up as pinhole leaks in sensitive plumbing over long periods, or metallic tastes if the water stands in copper lines. It also influences mouthfeel. Many people describe very low‑mineral water as “flat.” Providers that promote remineralization stages emphasize that bringing the pH up toward a more alkaline range and adding back small amounts of calcium and magnesium can improve taste and, in some cases, better align with health preferences.

Chlorine, Chloramine, and the Role of Pretreatment

Chlorine and chloramine are disinfectants added to many municipal supplies to control microbes. They are chemically active and can attack certain membrane materials. Thin‑film composite membranes, the most common high‑performance choice, are particularly sensitive to free chlorine.

To manage this, residential and commercial systems nearly always include activated carbon filters before the RO membrane when treating chlorinated water. These carbon blocks adsorb chlorine and many taste‑ and odor‑forming compounds. Some cellulose‑based membranes tolerate chlorine better, but they generally provide lower rejection and are used more selectively.

This has two important implications. First, from a gas‑filtration standpoint, chlorine and many chlorination byproducts are handled primarily by carbon, not by the RO membrane itself. Second, when you change filters or reconfigure a system, you must maintain that protective carbon stage if you are on chlorinated city water, or you risk prematurely damaging the membrane.

The table below summarizes how several key gases and related substances interact with a typical home RO setup.

Gas or substance |

How it behaves in RO treatment |

Best way to manage it in a home RO system |

Hydrogen sulfide (rotten‑egg odor) |

Passes largely through the membrane; RO alone is not an effective control |

Use upstream treatment such as oxidation and filtration or media designed for sulfur, often combined with carbon, before the RO stage |

Carbon dioxide |

Usually passes through the membrane, then forms carbonic acid and lowers pH slightly |

Accept that RO permeate will be low‑mineral and slightly more acidic; consider remineralization stages to adjust taste and reduce corrosivity |

Chlorine |

Can damage thin‑film composite membranes if not removed |

Install and maintain an activated carbon prefilter to protect the membrane and improve taste and odor |

Chloramine and some VOCs |

Not reliably removed by the membrane alone; partially addressed by carbon |

Combine RO with high‑quality activated carbon stages designed to target these compounds, both for health and taste |

Understanding these gas‑related effects helps explain why two RO systems with similar TDS readings can taste very different and why membrane life varies so widely between homes.

Pros and Cons of RO for Home Hydration

Health and Safety Benefits

When water reports or tests show multiple contaminants, reverse osmosis is one of the few point‑of‑use technologies that can address many of them at once. Public‑health advocates such as the Environmental Working Group have argued that regulatory frameworks often consider one contaminant at a time, even though real‑world water can contain mixtures of industrial chemicals, disinfection byproducts, agricultural residues, and metals. RO filters align with a multi‑contaminant treatment approach because they significantly reduce a broad spectrum of substances simultaneously.

Manufacturer and extension materials consistently document strong RO performance for lead, arsenic, nitrate, fluoride, many heavy metals, and a wide range of pathogens when systems are properly configured and maintained. For high‑risk populations such as infants, pregnant people, and people with compromised immune systems, this multi‑threat protection can be especially meaningful when combined with sound source protection and, for wells, regular testing.

RO also helps homeowners in regions where total dissolved solids are high. High‑TDS water can taste salty, metallic, or bitter. By bringing TDS down, RO improves taste directly and, indirectly, makes it easier to add back specific minerals in controlled amounts.

Taste, Minerals, and Remineralization

The most common hesitation I hear about RO is, “Doesn’t it remove the good minerals too?” The honest answer is yes. The membrane cannot tell the difference between calcium from a healthy aquifer and sodium from road salt; it removes both.

Several detailed homeowner‑focused articles and health discussions in the research notes make a few key points about this trade‑off. RO’s thoroughness means beneficial minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium are reduced along with undesirable ones. Fluoride added by many cities for dental health is also reduced.

The World Health Organization has raised concerns about relying exclusively on completely demineralized water long term, partly because of missing trace minerals and potential effects on corrosion. At the same time, the same sources note that most essential minerals in a typical diet come from food, not water. That nuance matters: low‑mineral water is not automatically harmful, but it changes taste and interacts differently with plumbing and the body.

To strike a balance, many modern RO systems incorporate a remineralization stage after the membrane. In these cartridges, very small amounts of minerals such as calcium and magnesium dissolve into the purified water, raising pH slightly and improving taste. Some manufacturers market this as “alkaline” RO water when the pH rises toward the high‑7s or low‑8s. Other systems provide optional mineral‑boost cartridges so homeowners can choose the taste profile they prefer.

In day‑to‑day practice, RO plus remineralization often produces what people describe as “crisp,” neutral‑tasting water that still has very low contaminants but does not feel as flat as untreated permeate.

Water Use and Efficiency

Water use is an important, often overlooked aspect of RO. Conventional point‑of‑use units can waste significant water as concentrate. According to the U.S. EPA’s WaterSense program, many common under‑sink systems send about 5 gallons or more of reject water down the drain for every gallon of treated water produced, and some very inefficient designs can waste up to about 10 gallons per gallon produced.

WaterSense‑labeled RO systems must limit reject water to about 2.3 gallons or less for every gallon of treated water. EPA estimates that replacing a typical unit with a WaterSense‑labeled model can save a household more than 3,100 gallons of water each year, adding up to roughly 47,000 gallons over the lifetime of the system.

If every point‑of‑use RO sold in the United States met this label, national savings would exceed 3.1 billion gallons annually, comparable to the yearly water use of tens of thousands of homes.

Other sources note that older residential RO units frequently waste roughly 3 to 4 gallons per gallon of treated water, while newer “high‑efficiency” designs can reduce that ratio closer to about 1 to 2 gallons of reject per gallon of product under favorable pressure conditions.

At the system‑design level, the recovery percentages described earlier also play into this. A unit designed for 20 percent recovery turns 100 gallons of feed into about 20 gallons of treated water and 80 gallons of concentrate. A unit designed for higher recovery uses water more sparingly but faces greater risk of scaling and fouling if pretreatment is not robust.

Maintenance and System Longevity

Because RO membranes separate contaminants at such a fine scale, they are sensitive to fouling, scaling, and chemical attack. Engineering and extension documents emphasize that sediment and carbon prefilters are essential to remove silt, sand, and oxidants like chlorine before water reaches the membrane. Without these, performance declines quickly.

For typical home units, guidance from water‑quality providers suggests that sediment and carbon prefilters usually require replacement every 6 to 12 months, depending on water quality and usage. Some whole‑house or high‑load systems, especially those described in industrial pros‑and‑cons discussions, need prefilters changed every few months. Membranes themselves often last about 2 to 5 years in residential service when prefilters are maintained and feedwater is not unusually harsh. Other sources recommend a replacement window of about 1 to 3 years under heavier duty.

Regular sanitization of the storage tank and distribution lines helps control biofilm growth. Monitoring TDS at the faucet over time gives a quick check on whether the membrane is still rejecting contaminants as expected. Industrial practice goes even further, tracking pressures, flows, and normalized performance metrics to catch problems early and perform cleaning in place before damage becomes irreversible.

From a homeowner’s perspective, the main takeaway is that RO is not a “set and forget” technology. It rewards regular, simple maintenance with many years of reliable service and punishes neglect with falling performance and higher long‑term costs.

Choosing and Using an RO System When Gases Matter

Start With Testing and a Clear Goal

Before choosing any treatment technology, university extension experts and the EPA strongly recommend testing your water or reviewing recent water quality reports. Public systems must provide Consumer Confidence Reports and meet federal standards, but distribution pipes and local plumbing can still introduce issues. Private well owners are entirely responsible for their own testing and treatment decisions.

It helps to define what you want to achieve. For some homes, the priority is clearly health‑related: reducing lead, nitrate, arsenic, or other contaminants of concern. For others, taste and smell are the drivers, such as metallic flavors, sulfur odors, or chlorine tastes. RO is often the right choice when both health and aesthetic concerns involve multiple dissolved contaminants that are hard to address with a single cartridge filter.

However, if the main problem is a dissolved gas like hydrogen sulfide, RO by itself is the wrong tool. In that case, the focus should be on gas‑specific treatment before considering RO.

Match Membrane and Pretreatment to Your Water

Once your goals are clear, the next step is choosing the right combination of membrane and pretreatment.

For most chlorinated city water, a thin‑film composite membrane plus sediment and activated carbon pretreatment is a strong choice. The carbon removes chlorine and many organic chemicals, protecting the membrane and improving taste, while the membrane handles metals, TDS, and a broad range of other contaminants.

If your feedwater contains little or no chlorine but has significant sediment or iron, you may need more robust mechanical filtration or even iron removal ahead of the RO membrane to prevent rapid clogging. In well‑water homes with hydrogen sulfide odors, specialized sulfur filters or oxidation and filtration units are typically placed before RO to address the gas that RO cannot handle.

In rare cases where you want to maintain a small residual of chlorine upstream, a cellulose‑based membrane may be considered because of its chlorine tolerance, but you must be prepared for lower contaminant rejection compared with a high‑performance thin‑film composite.

Decide Where RO Belongs in the Home

Reverse osmosis is usually best deployed as a point‑of‑use technology rather than whole‑house treatment. University extension materials and manufacturer guidance describe most residential systems as under‑sink or countertop units with a small storage tank and a dedicated faucet. They typically produce on the order of 10 to 35 gallons of treated water per day, which is enough for drinking and cooking for many households.

Whole‑house RO is used in some situations, such as very high TDS wells or specific industrial or agricultural needs, but it is significantly more expensive and complex to purchase, install, and operate. For most homes, a more practical strategy is to pair a point‑of‑use RO system for drinking and cooking with whole‑home filtration targeted at other issues, such as iron, manganese, or sulfur.

This layered approach gives you very high quality water at the taps where you drink and prepare food, while addressing broader aesthetic and equipment‑protection issues throughout the home without the cost and waste of full‑house RO.

Make RO as Sustainable as Possible

If you decide RO makes sense for your home, you can reduce its environmental footprint and operating cost by focusing on a few key design choices.

First, favor high‑efficiency or WaterSense‑labeled point‑of‑use systems where available. As noted earlier, these models limit reject water to about 2.3 gallons or less for each gallon of treated water and are independently certified to meet both performance and efficiency criteria. Over the life of the system, that efficiency difference can save tens of thousands of gallons compared with older designs.

Second, work with your installer or dealer to set recovery rates that balance water savings against fouling risk. Pushing recovery too high without adequate pretreatment can accelerate scaling and lead to more frequent membrane replacement, which undercuts both cost and sustainability.

Third, maintain prefilters and membranes on schedule. A heavily fouled membrane produces less water, wastes more, and may let more contaminants pass. Regular filter changes keep the system operating in its most efficient window.

Finally, remember that RO often replaces or reduces bottled water purchases. Several analyses in the research notes highlight the environmental benefits of cutting single‑use plastic, both in reduced plastic waste and in lowering the energy and emissions tied to bottling and shipping water. Over time, this shift can be significant.

FAQ: Everyday Questions About RO Membranes and Gases

Does a reverse osmosis system remove the rotten‑egg smell from my water?

Not reliably. Hydrogen sulfide gas, which causes the rotten‑egg odor, is specifically noted in university extension guidance as something RO does not remove effectively. The gas tends to pass through the membrane. To fix that smell, you usually need a sulfur‑specific treatment before the RO unit, such as oxidation and filtration or specialized media, often along with activated carbon.

Why does my RO water taste flat or slightly acidic?

Several technical references describe RO permeate as low‑mineral water with slightly lower pH because carbon dioxide passes through the membrane and forms carbonic acid, while buffering minerals are removed. That combination produces a mildly acidic, very low‑TDS water that many people experience as “flat.” Remineralization cartridges, which add small amounts of minerals back into the water, can bring the pH up and improve taste without giving up the contaminant‑reduction benefits.

Is RO always the best choice for home drinking water?

Not always. The EPA notes that most public water supplies already meet safety standards and that other treatment technologies with little or no water waste may be sufficient in many cases. RO becomes particularly valuable when water tests or local reports show multiple contaminants of concern, such as a combination of metals, nitrate, and various organic chemicals, or when you have high TDS that affects taste. The right choice depends on your specific water, health priorities, and willingness to maintain the system.

Closing Thoughts

When you understand how reverse osmosis membranes behave with both dissolved solids and gases, it becomes much easier to design a home hydration setup that truly fits your life. RO, paired with smart pretreatment for gases and thoughtful remineralization, can give you cleaner, better‑tasting water while respecting both your plumbing and the planet. If you start with a good water test and clear goals, you can treat RO as a precision tool rather than a one‑size‑fits‑all solution and build a hydration system that supports your health every time you turn on the tap.

References

- https://www.epa.gov/watersense/point-use-reverse-osmosis-systems

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reverse_osmosis

- https://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/html/g1490/build/g1490.htm

- https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/reverse-osmosis-water-filters-when-are-they-good-choice

- https://www.cloudwaterfilters.com/education/10-benefits-of-reverse-osmosis-systems?srsltid=AfmBOoov-z9eRubNWaKQGT2sqES3OFM3glSRWOtzV7yt3L7D0_I1_fwY

- https://complete-water.com/blog/industrial-uses-for-reverse-osmosis-ro-systems

- https://www.culligan.com/blog/the-benefits-of-having-a-reverse-osmosis-filtration-system-at-home

- https://espwaterproducts.com/pages/reverse-osmosis-advantages-and-disadvantages?srsltid=AfmBOooj3aDPvHNLWg63zrHll-vY-40OWQ752hyG7Ykh9IWSeSJ3lIB6

- https://isingsculligan.com/what-does-reverse-osmosis-remove-from-drinking-water/

- https://www.newater.com/reverse-osmosis-water-pros-cons/

Share:

Comparing Materials in Commercial and Residential Reverse Osmosis Systems

Understanding California’s Efficiency Certification Requirement for Reverse Osmosis (RO) Systems