Why Daily Flush Water Use Deserves More Attention

As a smart hydration specialist, I spend a lot of time thinking about the water you drink. But I also pay close attention to the water you never see: the gallons rushing through toilet tanks, urinals, distribution mains, and hidden pipes every day. Automatic flushing systems sit right at that intersection between water conservation, hygiene, and healthy plumbing.

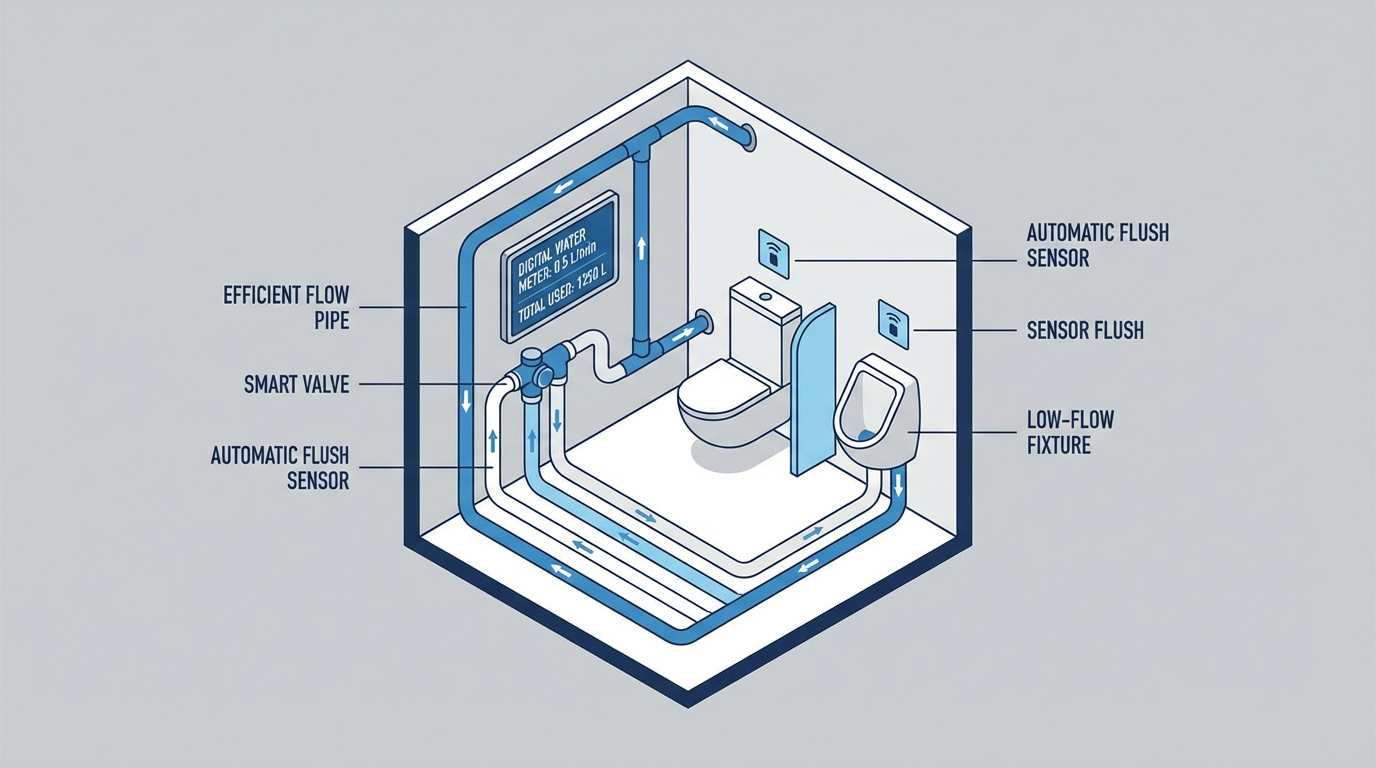

In offices, schools, restaurants, airports, and even in some homes, sensors now decide when and how often to flush. In theory, this should produce a perfect balance: clean fixtures, no need to touch handles, and just the right amount of water each time. In practice, the daily water consumption of automatic flushing systems can vary from impressively efficient to surprisingly wasteful, depending on how they are designed, calibrated, and paired with the fixtures they control.

To understand whether automation is helping or hurting your water footprint, you have to unpack two simple levers: how much water each flush uses and how often the system flushes, including leaks and “phantom” flushes. The research behind high‑efficiency fixtures, automatic flush valves, and automated pipe flushing gives us a clear, science‑based way to evaluate that daily use.

Flush Volume 101: Gallons Per Flush And Fixture Types

The starting point is gallons per flush, usually abbreviated as GPF. It is the volume of water released every time a toilet or urinal is flushed, and it is one of the biggest drivers of indoor water use. Research notes on water‑saving toilets indicate that toilets often account for about a quarter to a third of indoor household water consumption, so getting GPF right has an outsized impact on overall daily use.

Older toilets installed before the mid‑1990s commonly use around 3.5 to 7.0 gallons per flush. Federal standards that came into force in the early 1990s dropped that to 1.6 gallons per flush for new residential toilets, and later high‑efficiency designs pushed further to roughly 1.28 gallons per flush or less. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s WaterSense program identifies high‑efficiency toilets that meet strict performance criteria and use about 1.28 gallons per flush or lower, saving roughly 20 percent compared with the 1.6 gallon standard and much more when replacing a 3.5 gallon or higher legacy toilet.

For urinals, federal guidance and best‑practice documents from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Federal Energy Management Program describe high‑efficiency urinals designed to use 0.5 gallons per flush or less, with some models operating at only about 0.125 gallons per flush. By contrast, research on manual urinal valves describes situations where failed or misused handles waste about 13 to 16 liters per flush, which equates to roughly 3.5 to 4.0 gallons.

That creates a huge spread in daily consumption between a poorly managed manual urinal and a well‑designed high‑efficiency unit.

A concise way to see these differences is to compare fixture types and their typical volumes.

Fixture type |

Typical flush volume (gallons per flush) |

How automation fits in |

Legacy residential toilet (pre‑mid‑1990s) |

About 3.5 to 7.0 |

Usually manual handle; high daily use if flushed frequently |

Standard code‑era toilet (post‑1992) |

About 1.6 |

Can be manual or sensor‑controlled via flushometer |

High‑efficiency toilet with WaterSense label |

About 1.28 or less |

Often tank‑type or flushometer; automation mainly affects how often it flushes |

High‑efficiency urinal |

About 0.5 or less (down to about 0.125) |

Commonly paired with automatic flush valves in commercial restrooms |

Poorly managed manual urinal |

Roughly 3.5 to 4.0 (from 13 to 16 liters) |

When left running or over‑flushed, daily use can spike dramatically |

From a daily water‑use perspective, this table tells a simple story. First, fixture efficiency matters: dropping from 3.5 gallons to around 1.28 gallons per flush cuts the volume by more than half. One analysis in the research notes shows that replacing a 3.5 gallon per flush toilet with a 1.28 gallon model in a four‑person home, using five flushes per person per day in the calculation, can save about 16,000 gallons of water per year. Second, automation by itself does not change gallons per flush; it changes how often that full volume is released.

Modern High‑Efficiency Toilets: Better Than Early “Low‑Flow”

Early low‑flow toilets in the 1990s created lasting skepticism because they often clogged and required multiple flushes. That history still colors how people feel about any device that claims to save water. Modern high‑efficiency toilets, especially those labeled under EPA’s WaterSense program, are not simply smaller tanks. They use redesigned bowl contours, larger and better‑shaped trapways, and, in some models, pressure‑assisted tanks to deliver strong, reliable flushes with 1.28 gallons or less. The WaterSense label is only awarded to toilets that are independently certified to meet national plumbing performance standards for waste removal as well as water efficiency, which reduces the risk of chronic double‑flushing or backups under typical use.

Federal best‑practice guidance recommends WaterSense‑labeled toilets with effective flush volumes of 1.28 gallons per flush or less for residential tank‑type units and high‑efficiency flushometer toilets with similar performance for commercial settings. The same guidance encourages facilities to confirm performance using independent testing data such as Maximum Performance (MaP) scores, which is an important step if you want to avoid trading water savings for user complaints.

In my field work with building owners who upgraded from older toilets to WaterSense‑labeled models, I have consistently seen two things: better control over daily water use and fewer surprises on monthly water bills, especially when they combine these fixtures with careful maintenance of flappers, fill valves, and flush valves.

What Automatic Flushing Systems Actually Do

When people talk about “automatic flushing,” they often mean very different technologies. Some devices are attached directly to toilets and urinals. Others are installed out in the water distribution system or inside building plumbing, flushing pipes rather than fixtures. All of them share a basic promise: they flush at the right time, using a defined volume, without relying on someone to remember to push a handle.

Automatic Flush Valves In Toilets And Urinals

Automatic flush valves for toilets and urinals use motion or infrared sensors to detect a user and trigger a flush without manual contact. According to technical descriptions of these systems, the sensor sees a person approach, stay within a certain distance, and then leave. Once the user steps away, the control electronics open a solenoid valve for a short, calibrated period, delivering a preset flush volume and then shutting off.

Research on automatic urinal flushing designs shows how this works in more detail. An infrared LED continuously emits light; when a person stands about a foot and a half away, the reflected infrared signal is picked up by a photodiode, and an Arduino‑type controller opens a 24‑volt solenoid valve connected to the water line. The solenoid is normally closed, so water only flows during the timed flush, and the plastic valve body helps avoid corrosion while retrofitting into existing plumbing.

The hygiene benefit is obvious: touch‑free operation reduces contact with germ‑laden surfaces and encourages consistent flushing, which keeps restrooms cleaner and reduces odors. This is particularly valuable in high‑traffic public restrooms and high‑sensitivity environments such as airports, schools, and medical facilities. Articles from commercial plumbing specialists emphasize that automatic flush valves support touchless restroom designs and improve user satisfaction by reducing the number of unflushed fixtures.

On the water‑use side, automatic flush valves can reduce waste compared with manually operated valves that are sometimes left running or pumped repeatedly. One technical article notes that misuse of manual flush valves in public washrooms can waste about 13 to 16 liters of water per use, which is around 3.5 to 4.0 gallons, simply because people fail to close the valve fully. By contrast, a sensor‑based system provides a short, controlled flush after each use and shuts off automatically, which can be significantly more efficient when hundreds or thousands of people use the fixtures each day.

Reports from manufacturers of automatic flush valves point out that these systems, when properly calibrated and paired with high‑efficiency fixtures, can save thousands of gallons of water annually in high‑traffic restrooms. Because lower water use also reduces the energy needed to treat and pump that water, they can contribute to lower greenhouse gas emissions and help buildings meet green certification criteria such as LEED and WaterSense‑aligned water‑efficiency targets.

However, the research also makes clear that sensor quality and calibration are critical. Poorly adjusted sensors can trigger multiple flushes per visit or miss users entirely. Studies summarized by plumbing and water‑efficiency experts have found that older generations of automatic faucets and flush valves sometimes used as much or more water than manual fixtures because of repeated “phantom flushes” and long activation times when people struggled to find the sensor’s “sweet spot.”

Automatic Flushing Stations On Water Distribution Mains

Automatic flushing is not just about bathrooms. Municipal water utilities use dedicated automatic flushing stations on low‑use dead‑end water mains to keep water fresh and maintain disinfectant residuals. Instead of sending crews to open fire hydrants once or twice per year, they install a device whose only job is to flush water on a programmed schedule without on‑site staff.

On dead‑end mains with very low flow, chlorine residuals can dissipate within about two weeks. Once disinfectant levels fall below roughly 0.2 parts per million of free chlorine or 0.5 parts per million of combined chlorine, they no longer effectively control microbial pathogens. At the same time, disinfection by‑products begin to form when chlorine reacts with naturally occurring organic matter. Benchmarks from utility case studies show that disinfection by‑products often begin to form within around four to seven days in stagnant chlorinated water. Those compounds have been associated with health concerns such as heart disease, liver damage, and nervous system effects when people ingest, inhale, or absorb them.

Automatic flushing stations address this by running at low flow but higher frequency. Utilities program them, often via handheld or Bluetooth controllers, to open at set times, for example three days per week for a fixed number of minutes at night. By flushing older water and pulling fresh water through the line, they maintain safe chlorine residuals and reduce disinfection by‑product formation while also improving color and taste in older iron pipe networks.

Bench testing referenced in the research notes found that automatic flushing stations can achieve water‑quality goals using up to 50 percent less water than conventional hydrant flushing. The reason is purely hydraulic: automatic stations operate at about 20 to 200 gallons per minute, whereas hydrant flushing often runs at roughly 1,500 gallons per minute, so the automatic station needs far less total volume to replace the aging water in a low‑flow main. Daily and weekly water use from these devices is intentional and controlled rather than sporadic and extreme.

Emerging Automated Flushing Inside Buildings

Inside building plumbing, the balance between water conservation and water quality becomes even more delicate. A peer‑reviewed study on automated flushing in building plumbing points out that drinking water quality can deteriorate as water sits in pipes. Loss of disinfectant residual, increased release of lead and copper from plumbing materials, and growth of biofilms including pathogens are all concerns.

Regulations generally require utilities to maintain residual disinfectant and control corrosion up to the building entry, but responsibility at the tap often falls to building managers and residents. Many existing guidelines tell people to flush faucets for a fixed duration, often around 30 seconds to 2 minutes, even though the time required for fresh main water to reach a particular tap can range from a few seconds to more than 10 minutes and, in complex systems, even longer than an hour. That means fixed‑time flushing can be both unreliable and wasteful, especially in water‑scarce regions.

The same study highlights that in some hospital hot‑water systems, reducing Legionella counts from tens of thousands of colony‑forming units per liter to essentially zero required flushing some taps as frequently as every two hours. That level of manual flushing is rarely practical. This has led researchers to explore sensor‑based automated flushing inside buildings using measurements like oxidation–reduction potential and temperature as proxies for disinfectant level and water age. These low‑cost sensors can, in principle, control valves to flush just enough, and just often enough, to keep water safer without running taps for unnecessarily long periods.

Interestingly, the authors also point out a paradox: many building technologies that use proximity sensors, such as automatic faucets and toilets, are designed primarily for water conservation and touchless convenience. By reducing everyday water use and shortening run times, they can unintentionally increase water age in pipes, potentially raising the risk of contamination unless balanced with smarter, targeted flushing strategies elsewhere in the plumbing system.

Daily Water Consumption: When Automation Helps And When It Hurts

Daily water consumption from automatic flushing is the product of three factors: the fixture or system’s gallons per flush, how often it flushes, and how much extra water is used for leak losses, phantom activations, or pipe flushing. The research paints a nuanced picture.

When Automation And Efficiency Work Together

The strongest water‑saving results appear when high‑efficiency fixtures are paired with well‑calibrated automation. High‑efficiency toilets and urinals with volumes around 1.28 gallons per flush for toilets and 0.5 gallons per flush or less for urinals dramatically reduce the amount of water used each time. When you combine that with sensor‑activated flush valves that deliver exactly that volume once per use and then shut off, daily water consumption can be both predictable and lower than with less efficient manual fixtures.

Manufacturers and plumbing experts report that high‑traffic facilities such as restaurants, hotels, and shopping centers can save thousands of gallons of water annually by upgrading to automatic flush valves paired with high‑efficiency bowls and urinals. In my own audits of commercial restrooms, I often see that the biggest improvements come from eliminating chronic misuse, such as manual handles held down for long flushes or left running. Once the flush volume is fixed and the sensor is tuned to trigger only after use, daily usage becomes much more manageable.

At the scale of a household, that four‑person example from the research notes is instructive. Using a 3.5 gallon per flush toilet five times per person per day adds up quickly. Replacing it with a 1.28 gallon per flush high‑efficiency model reduces the annual water used for flushing by roughly 16,000 gallons. Even if daily patterns vary, that shows how powerful flush volume is in shaping daily consumption. Automatic flushing is not required to achieve that gain, but when it is present and correctly configured, it helps ensure those efficient volumes are delivered consistently.

When “Phantom Flushing” Drives Daily Use Up

The darker side of automation appears when sensors are oversensitive, poorly placed, or not maintained. The term “phantom flushing” captures that moment when an automatic toilet flushes even though no one is finished using it, or flushes again and again as a person moves slightly. Essays examining sensor toilets in public restrooms note that premature and repeated flushes not only annoy users but also waste gallons of clean water during an ongoing global water crisis.

Duke University’s facilities team ran into this problem during a severe water shortage with Stage IV restrictions in their city. They discovered that some automatic flush toilets on campus used the same volume per flush as their manual counterparts but were flushing multiple times per visit because infrared sensors were triggered when people bent down or stepped in and out of the detection field. To conserve water, plumbers literally taped over the sensors and instructed users to press the manual override buttons. Duke began converting many automatic units back to manual operation and evaluating dual‑flush handles that allow a lower‑volume flush for liquid waste. They expected these changes to save thousands of gallons of water per day as they scaled across campus.

Water‑efficiency experts reviewing automatic faucets and flush valves have echoed similar concerns. In some studies from the past decade, older or cheaply designed automatic fixtures consumed as much or more water than manual ones because of repeated activations, extended run times when people struggled to find the sensor, and lack of fine‑tuned calibration. When that behavior is multiplied across a busy airport, stadium, or office complex, daily water consumption can spike far beyond what the fixture’s nominal gallons‑per‑flush rating would suggest.

In my site visits, I treat every unexpected flush as a signal.

If a stall flushes when someone shifts their weight or stands up slowly, there is a good chance daily water use is higher than it needs to be. The solution is almost always calibration, not abandonment: adjust sensor range and timing, verify valve closure, and ensure the device matches the bowl or urinal it controls.

Daily Water Use From Pipe Flushing

Automatic flushing stations on distribution mains and potential automated flushing at building taps add another layer to daily consumption. These systems deliberately release water; their purpose is to protect water quality rather than to clear visible waste.

On dead‑end mains, an automatic flushing station might run several times per week, at night, for short intervals. Because it operates at lower flow rates than a fire hydrant and uses just enough water to replace aging water in the pipe, total weekly and daily use can be considerably lower than sporadic hydrant flushing. Bench tests showing up to 50 percent lower water use than hydrant practices support this. So while these systems do consume water daily or weekly, they do so in a measured way that aligns with public health goals and regulatory requirements on disinfectant residual.

Inside buildings, the daily water cost of manual versus automated flushing at taps depends heavily on plumbing layout and water quality risk. The research on building plumbing demonstrates that guidelines recommending fixed flushing durations can be both insufficient and wasteful because the time needed to reach fresh main water can vary from seconds to over an hour. In settings with high vulnerability, such as hospitals facing Legionella risks, high‑frequency flushing every couple of hours may be necessary for some taps, which raises questions about how to balance safety with conservation. Sensor‑controlled flushing that responds to real‑time indicators like oxidation–reduction potential and temperature offers a way to target flushing where and when it is actually needed, potentially cutting unnecessary daily water use compared with blunt, time‑based routines.

Health, Hygiene, And Water Quality Trade‑Offs

When you evaluate automatic flushing purely by daily water consumption, it is easy to focus on gallons saved or lost. From a water wellness perspective, however, the health context is just as important.

Research on toilet plumes and aerosols, including work from John Crimaldi’s fluid‑dynamics lab and a hospital study on C. difficile, shows that flushing lidless toilets can produce powerful aerosol plumes that spread droplets across bathroom surfaces within about 90 minutes. Automatic flushing does not change the physics of those plumes; it mainly changes when and how often they occur. Some commentators argue that if anything should be automated, it is toilet lids, which could close before flushing to contain aerosols and pathogens. That design direction would preserve the hygiene benefits of touchless flushing while reducing exposure to airborne contaminants.

In distribution mains and building plumbing, water quality considerations are even more direct. If chlorine residuals fall too low or water sits long enough for disinfection by‑products to form, consumers at the tap may face higher risks from microbial pathogens or chemical by‑products. The hydrant flushing and automatic station research makes it clear that flushing is not waste for its own sake; it is a tool to keep water chemically and microbiologically safer. Similarly, in building hot‑water systems where Legionella can proliferate, flushing is a control measure. Automation here can help reduce the daily volume required by targeting flushing to times and fixtures where it matters most.

From a smart hydration standpoint, the goal is not simply to minimize every gallon of flushing, but to make sure every gallon serves a purpose. Water used to prevent disease, reduce lead and copper exposure, or maintain safe disinfectant levels has health value. Water lost to leaks, phantom flushes, or poorly configured systems does not.

Practical Guidance For Homes, Facilities, And Utilities

In Homes: Focus On Flush Volume And Leaks First

For most households, the biggest daily gains come from fixture efficiency and leak control rather than from installing automatic flush toilets. If your toilets were installed before the mid‑1990s and use around 3.5 gallons per flush or more, upgrading to a WaterSense‑labeled model around 1.28 gallons per flush can substantially cut your daily and annual water use. EPA WaterSense information notes that these toilets are independently tested for both water savings and performance, and many local utilities offer rebates from about $25 to more than $200 for installing them. Over time, the water‑bill savings can exceed the cost of the upgrade, making it more expensive in the long run not to switch.

At the same time, a leaking toilet can undo much of that efficiency. A water‑automation company cited in the research notes estimates that a single leaking toilet can waste up to 200 gallons of water per day. Common causes include a flapper that has become brittle or warped due to age or chlorine and mineral exposure, a chain that is too long and gets trapped under the flapper, or fill and flush valves that fail to close properly. Routine inspections and simple repairs often resolve these problems.

For homeowners who want additional protection, there are battery‑powered leak‑detection systems designed to mount behind the toilet, connect to the supply line, and shut off water automatically when a leak is detected. One such system described in the research is installed without a plumber using double‑sided tape, a water sensor, hoses, and AA batteries, and it can even qualify some homeowners for insurance benefits. From a daily water‑use perspective, the value is straightforward: preventing a leak that wastes hundreds of gallons per day protects both your water bill and your home.

In my experience, most families do not need automatic flush toilets to manage daily water well. A high‑efficiency, well‑maintained manual toilet, combined with good hygiene habits and leak control, delivers excellent performance with predictable daily consumption.

In Commercial And Institutional Restrooms: Integrate Efficiency With Smart Automation

Large facilities face very different usage patterns. Hundreds or thousands of people may use restrooms every day, and user behavior is more variable. Here, the combination of high‑efficiency fixtures and carefully configured automation can have a large impact on daily water consumption.

Federal best‑practice guidance advises facilities to start by assessing existing waste‑line design, water pressure, water quality, and user types before selecting new toilets and urinals. For tank‑type residential fixtures in campus housing, WaterSense‑labeled models at about 1.28 gallons per flush or less are recommended. For flushometer‑type toilets, high‑efficiency models using no more than about 1.28 gallons per flush should be chosen, and conventional urinals should be replaced with high‑efficiency units using around 0.5 gallons per flush or less, with some advanced designs down near 0.125 gallons per flush. It is essential that the valve’s flushing capacity matches the bowl or urinal design; mismatches can cause poor performance and user frustration.

Automatic flush valves make the most sense in these environments when they are paired with those high‑efficiency fixtures. Facility managers should specify modern sensor assemblies with reliable infrared detection, set appropriate detection distances, and tune flush timing so that a single, complete flush occurs after each use. Regular maintenance is important to clean sensors, check operation, and replace batteries as needed.

The experience at Duke University during its water shortage is a valuable cautionary case. When auto‑flush toilets are too sensitive, daily water use rises sharply because each user can trigger multiple full‑volume flushes. Facilities should be prepared to adjust or, in drought emergencies, temporarily disable or convert automatic systems to manual when phantom flushing becomes visible. Evaluating water‑meter data before and after such changes can help quantify the impact and guide long‑term decisions, such as retrofitting dual‑flush handles that allow lower‑volume flushes for liquid waste while reserving full flushes for solids.

For Utilities And Large Campuses: Use Automatic Flushing Strategically

Utilities and large campuses operate at a different scale but face similar trade‑offs. On one hand, they want to minimize nonessential water use. On the other, they must comply with regulations on disinfectant residual and protect public health by limiting disinfection by‑products and microbial growth in low‑flow zones.

Research on automatic flushing stations shows that these devices, when properly located on dead‑end mains, can maintain safe chlorine residuals and reduce disinfection by‑product formation while using up to half the water required by traditional hydrant flushing. Running them at night, when demand is low, also minimizes service disruptions. For utilities, the key is to program flushing frequency and duration based on water‑quality data rather than rigid schedules, so that daily water use is matched to actual need.

In irrigation networks, such as subsurface drip systems for alfalfa, automatic flushing valves at the line end offer another perspective. A study comparing two automatic flushing valve types with designed flushing durations of 20 seconds and 70 seconds found that the longer‑duration valve improved flow uniformity and anti‑clogging performance, extending the time to moderate clogging by roughly 180 percent compared with the control system without that valve. Although these systems are in agriculture rather than drinking water, the lesson carries over: if automatic flushing improves hydraulic performance and extends system life, the water used in each flushing event can be justified by the reduced need for repairs and replacements.

For large campuses and health‑care facilities, emerging sensor‑mediated flushing at building taps will likely become an important tool. By using oxidation–reduction potential and temperature sensors to detect when fresh disinfected water has reached a tap, these systems can automate flushing in a way that protects water quality while minimizing daily water use. The research shows that this approach can correct for highly variable pipe layouts and reduce the risk that fixed‑time manual flushing either wastes water or leaves people exposed to degraded water in their fixtures.

FAQ: Common Questions About Automatic Flushing And Water Use

Do automatic flush toilets always use more water than manual toilets?

No. Automatic flush toilets use the same volume of water per flush as comparable manual toilets; the difference lies in how often that volume is released. When sensors are well calibrated and paired with high‑efficiency fixtures around 1.28 gallons per flush or less, daily water use can be lower than in restrooms with older, higher‑volume manual toilets that users may flush repeatedly or misuse. However, when sensors are oversensitive or poorly placed, phantom flushing can drive daily water use above that of manual systems, as real‑world experiences at places like Duke University have shown.

Is it ever worth using extra water for flushing?

Yes, when that water protects health and long‑term system performance. Utilities use automatic flushing stations on dead‑end mains to maintain chlorine residuals and limit disinfection by‑products, which can have serious health implications if left unchecked. In buildings, flushing hot‑water systems can reduce risks from pathogens such as Legionella. Studies indicate that in some hospital systems, very frequent flushing is required at certain taps to bring bacterial counts down, which has clear public health value. The key is to use targeted, data‑informed flushing rather than blanket high‑volume routines, so that every gallon used serves a safety function.

As a homeowner, what has the biggest impact on my toilet‑related daily water use?

Based on the research, three factors dominate: the flush volume of your toilets, the presence or absence of leaks, and how often you flush. Upgrading from a 3.5 gallon per flush legacy toilet to a 1.28 gallon per flush high‑efficiency model can save on the order of tens of thousands of gallons per year for a four‑person household, according to one analysis that assumes five flushes per person per day. Fixing leaks is equally important; a leaking toilet can waste up to about 200 gallons per day, while high‑efficiency, well‑maintained toilets keep daily use predictable and much lower. Automatic flush mechanisms are generally less important for homes than for public restrooms; in most houses, thoughtful fixture selection and good maintenance deliver the best results.

Closing Thoughts

Automatic flushing systems can be either powerful allies or quiet saboteurs of water wellness. When they are matched with high‑efficiency fixtures, tuned carefully, and guided by real water‑quality data, they help keep both people and plumbing healthy while keeping daily water use in check. When they are misapplied or neglected, every unnecessary flush is a hidden sip taken away from your community’s shared water supply. As you think about the water flowing through your home or facility, aim for that sweet spot where each flush is intentional, efficient, and in service of cleaner, safer hydration at the tap.

References

- https://www.academia.edu/72540140/Automatic_Urinal_Flushing_System

- https://www.azwater.gov/conservation/conservation-technologies

- https://www.energy.gov/femp/best-management-practice-6-toilets-and-urinals

- https://commonreader.wustl.edu/fear-of-flushing/

- https://today.duke.edu/2007/12/autoflush.html

- https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2025Agric..15.1107L/abstract

- https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/www3/watersense/pubs/flush_fact_vs_fiction.html

- https://www.csus.edu/experience/innovation-creativity/sustainability/_internal/_documents/ir-faucet.pdf

- https://nmwrri.nmsu.edu/footer_pages/nm-wrri-library-database-files/wrri-library-pdfs/wrrilibrary5/005425.pdf

- https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/ccc97cba-295c-40b9-8848-6c128592def5/content

Share:

How Capacitive Touch Control in Smart Faucets Achieves Water Resistance

Understanding the Effectiveness of 253.7 nm Wavelength UV Lamps