As a smart hydration specialist, I meet many homeowners who proudly tell me, “We drink natural spring water with low TDS, so we don’t need a fancy RO system, right?” It is a fair question. If your water already looks clear and tests “low” on a TDS meter, installing reverse osmosis (RO) can feel like overkill.

The reality is more nuanced. Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) and reverse osmosis are powerful concepts, but they are often misunderstood. In this guide, I will walk you through what low TDS spring water really means, when an RO system is helpful or unnecessary, and how to protect both your family’s health and your home’s hydration experience without chasing “purity” at all costs.

How TDS Really Works

Total Dissolved Solids are everything in your water that is not H₂O: minerals like calcium and magnesium, salts such as chlorides and sulfates, trace metals, and small amounts of organic matter. Several water quality resources define TDS as a broad indicator of water’s mineralization and overall dissolved content, measured in parts per million (ppm) or milligrams per liter (mg/L).

Common dissolved substances include calcium, magnesium, sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, chloride, sulfate, and trace elements such as iron, zinc, or even pollutants like nitrates and pesticides. As the Los Angeles Public Library’s water-quality education materials explain, TDS captures both the healthy and the harmful in a single number. A simple handheld TDS meter measures electrical conductivity and converts it to an approximate ppm value, giving a quick snapshot of how “loaded” your water is, but not telling you what those solids are.

This is crucial. A TDS of 250 ppm might be mostly beneficial calcium and magnesium in a natural mineral water. The same TDS in an agricultural area could include nitrates or pesticide residues.

As one TDS explainer from a mineral water brand puts it, the composition of dissolved solids matters more than the number alone.

TDS Versus Hardness And Contamination

Several sources emphasize that TDS is not the same as water hardness. Hardness mainly reflects calcium and magnesium, while TDS includes all dissolved substances. You can have water with moderate TDS that is not particularly hard, like some natural mineral waters with around 300 mg/L TDS but relatively low hardness values. You can also have high TDS driven by sodium or other salts without major hardness issues.

TDS is also not a direct contamination test. Guides from drinking-water educators and filtration companies consistently note that harmful contaminants such as pesticides, industrial chemicals, or microbes can be present even when TDS is low. Conversely, high TDS often signals mineral-rich water that could be safe but might taste strong or cause scale. This is why relying on TDS alone to declare water “good” or “bad” is misleading.

What Counts As “Low” TDS, And Why It Matters

Different organizations and water experts converge around similar TDS bands for drinking water, based on taste and palatability studies as well as regulatory guidance.

Here is a simplified view synthesized from multiple sources that reference World Health Organization (WHO) and national guidelines:

TDS range (ppm) |

Typical description |

Common notes from sources |

0–50 |

Very low / demineralized |

Very pure, often RO or distilled; can taste flat; may lack minerals |

50–150 |

Excellent / ideal for everyday drinking |

Clean taste, useful minerals; often recommended “sweet spot” |

150–300 |

Good to ideal for taste and health |

More mineral flavor; still generally preferred for hydration |

300–500 |

Fair to acceptable |

Safe in many cases; taste becomes stronger, sometimes “hard” |

500–900 |

Poor or “not ideal” |

Often salty or bitter; treatment usually advised |

>900–1000 |

Unacceptable / unsafe for routine drinking |

Typically needs filtration before use |

Chanson-style guides and several TDS explainers suggest 50–150 ppm as an excellent range for drinking, balancing taste and mineral content. Others, including wellness brands and TDS-focused articles, describe 150–300 ppm as a good or ideal band for both taste and health, with water above about 500 ppm often needing treatment.

From the spring and mineral water side, global standards for “natural mineral water” generally require at least 250 mg/L TDS. Mountain Falls, for example, highlights a profile around 345 mg/L as being in an optimal 300–500 mg/L band for flavor and mineral support. On the lower side, brands like On Take Water position a target range of roughly 70–120 ppm as a sweet spot for daily hydration: low enough to taste crisp and clean, but high enough to carry essential minerals such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium.

Health Aspects Of Low Versus Very Low TDS

Minerals in water are not your only source of nutrients, but they do contribute. Multiple articles point out that calcium in drinking water supports bone density; magnesium aids muscle and nerve function; bicarbonate helps buffer acid load and support digestion; and trace minerals like silica may help with connective tissue and bone health. Natural mineral waters with TDS in the medium range often highlight their contribution to daily magnesium and calcium intake.

At the same time, resources from the Water Quality Association remind us that the fundamental roles of water in the body—hydration, temperature regulation, nutrient transport—are carried out by H₂O itself, not by the dissolved solids. In its technical paper on low TDS water, the association notes that agencies worldwide do not have scientific data showing that drinking low TDS water in the range of about 1–100 mg/L causes adverse health effects. Their position is that health-based guidance focuses more on avoiding excessively high TDS levels, typically above about 500 mg/L.

However, several other sources raise reasonable concerns about extremely low TDS drinking water, especially below about 50 ppm. Summaries of a World Health Organization study and related commentary suggest that long-term consumption of demineralized water can reduce intake of calcium and magnesium, particularly in populations whose diets are already marginal. Articles from Paqos, Romegamart, Waltr, and Pure Aqua collectively associate very low TDS water with bland taste, reduced mineral intake, possible digestive discomfort, and in some interpretations, potential contributions to fatigue, muscle cramps, and suboptimal bone or tooth mineralization if the diet does not compensate.

Some manufacturers, such as Life Sciences Water, go further and describe zero-TDS water as “electron deficient,” speculating that it might draw minerals from bones over the long term. This is a more speculative view and not one broadly endorsed in regulatory documents, but it illustrates the level of concern some hydration experts and brands express about routinely drinking water that has been stripped down to essentially pure H₂O.

The common thread is this: low TDS in the range of roughly 50–150 ppm is generally seen as excellent for daily drinking, while extremely low TDS below about 50 ppm sits in a gray area. It may be safe for many people, especially with a nutrient-dense diet, but multiple authors recommend remineralization or blending to avoid relying exclusively on ultra-pure water for everyday hydration.

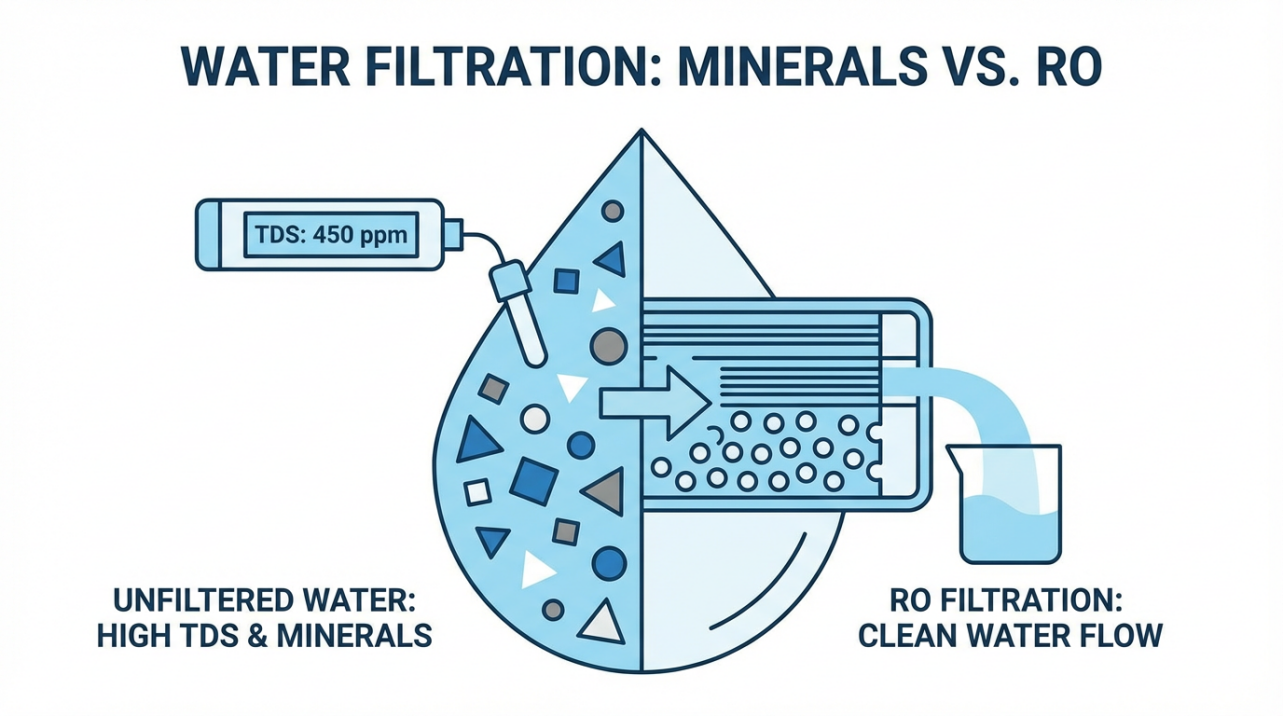

Reverse Osmosis: What It Does And Why It Is So Powerful

Reverse osmosis is one of the most effective ways to lower TDS and remove a broad range of contaminants. RO pushes water through a semi-permeable membrane that rejects most dissolved solids. Several technical and consumer-oriented sources note that a properly functioning RO system can typically remove about 95–99 percent of dissolved solids.

If your spring water has a TDS of 200 ppm, and your RO membrane removes 95 percent of that load, your treated water will be around 10 ppm.

That number looks impressive on a meter, but you have also removed almost all of the naturally occurring minerals that gave the water its flavor and nutritional contribution.

RO systems are widely recommended for high-TDS water, especially above about 500 ppm. Articles from Houston Water Solutions, APEC, and others highlight that high TDS often correlates with issues like salty or bitter taste, scale buildup in heaters and appliances, and potential co-occurrence of harmful contaminants such as arsenic or nitrates. In those cases, RO is a workhorse technology that can drastically reduce TDS and improve both taste and safety.

RO also shines where specific contaminants are a concern, regardless of TDS. Educational materials from libraries and water purifiers emphasize that TDS is only one dimension of water quality. You can have relatively low TDS water that still contains problematic substances like pesticides, herbicides, or traces of industrial chemicals. RO membranes, often combined with carbon filters and ultraviolet treatment, address many of those more elusive contaminants better than most basic filters.

The Downsides Of RO For Low TDS Water

When source water already has low or moderate TDS (for example, 80–150 ppm) and is microbiologically safe, RO can easily push you into the “very low TDS” zone below 50 ppm. That brings several trade-offs.

First, taste. Many sources agree that very low TDS water tends to taste flat or bland. Mineral-balanced water in the 50–300 ppm range usually has a fresher, more satisfying taste and mouthfeel, while ultra-pure water feels “empty” on the palate. This is one of the reasons why high-end mineral waters lean into their TDS numbers and mineral profiles the way wineries lean into terroir.

Second, mineral contribution. RO removes beneficial minerals along with potential contaminants. Summaries from Paqos, Romegamart, Waltr, and Pure Aqua all note that if you live on very low TDS water without getting adequate minerals from food and other sources, you may slowly erode your intake of calcium, magnesium, and other electrolytes that support bone health, heart rhythm, and muscle function.

Third, water chemistry and plumbing. Several discussions of low TDS water point out that demineralized water can be more chemically aggressive. Waltr, for instance, describes very low TDS water as more acidic and more likely to leach metals like copper from household plumbing. This does not mean it is dangerous by default, but it does mean that zero-TDS water is not automatically “gentler” on your system.

These concerns do not mean RO is bad. They mean that RO is a strong tool that needs to be matched to your source water and then finished correctly, especially when you are starting from an already low TDS spring.

Do You Really Need RO If Your Spring Water Has Low TDS?

This is the real decision point for many households. The answer depends on three things: what else is in the water beyond its TDS number, your health context, and your taste and appliance goals.

When RO Is Probably Unnecessary

If your spring source is regularly tested, consistently low in contaminants, and sits in that appealing TDS range around 70–150 ppm, a full RO system is often not the first thing I recommend. On Take Water’s approach is a good example of the philosophy here: multi-stage filtration to remove harmful chemicals, bacteria, and heavy metals, followed by remineralization to hold TDS in a roughly 70–120 ppm band. They are not chasing zero; they are targeting balance.

For a household drawing from a clean, protected spring at, say, 90 ppm TDS with no significant nitrates, heavy metals, or microbial issues, a high-quality carbon block filter combined with UV disinfection can be a very smart solution. You preserve the beneficial minerals and natural character of the water, avoid the ultra-low TDS debate entirely, and still protect your family from everyday contaminants.

In my own field work, when I encounter a low TDS spring that has been tested clean and the homeowners like the taste, we often focus on polishing rather than obliterating the water: sediment filtration, carbon for taste and odor, and sometimes UV if there is any doubt about microbial safety. With those layers in place, adding RO solely to push TDS lower usually does not offer much additional health benefit.

When RO Still Makes Sense For Low TDS Spring Water

There are plenty of scenarios, however, where RO is still worth strong consideration even when your TDS looks modest.

If your spring is in an agricultural or industrial region, fertilizers, nitrates, herbicides, or industrial organics can seep into groundwater without dramatically changing TDS. Public science education materials stress that low TDS does not guarantee a lack of these contaminants. A TDS meter cannot see a pesticide molecule.

If your plumbing infrastructure involves older pipes, you may be facing trace lead or copper. Again, TDS may not spike dramatically, but the health impact can be significant over time, especially for children. Several TDS and water-quality explainers list heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, cadmium, and copper as key concerns that call for advanced treatment.

If anyone in the household is immunocompromised, pregnant, or very young, the extra margin of safety from a well-designed RO system can be valuable. While the Water Quality Association notes that low TDS itself is not shown to harm health, other sources highlight that vulnerable groups are more sensitive to both contaminants and mineral imbalances.

In these situations, I often recommend RO as a core barrier, but with an important twist: remineralization and TDS control on the back end.

Getting RO Right On Low TDS Spring Water: Remineralization And Target TDS

If you decide RO is appropriate for your low TDS spring, your goal shifts from “make TDS as low as possible” to “remove what we do not want and then restore what we do.”

Why Remineralization Matters

Multiple sources that advocate for RO also insist on adding minerals back. Articles from LANGWATER, Ion Exchange, Chanson-style guides, Paqos, and DrinkEvocus share a similar message: do not aim for zero TDS. Instead, let RO strip away contaminants and excess salts, then use a mineral cartridge, alkaline filter, or drops to bring TDS back into a healthy, palatable range.

LANGWATER, for instance, describes a system where RO is followed by remineralization to target around 250 mg/L TDS, aligning with WHO “excellent” taste ratings and maintaining key minerals. Several other sources point to 50–150 ppm as an excellent everyday band, with 150–300 ppm still very good. Mineral brands such as Aava and Mountain Falls sit in the 280–345 mg/L range and lean on their calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate content to support bones, muscles, and digestion.

On the flip side, Life Sciences Water illustrates the opposite extreme: devices that push toward zero TDS and then attempt to add back minerals and alkalinity while marketing numerous “alkaline health benefits.” Their own messaging still acknowledges that zero-TDS water on its own may not be ideal long term and advocates for mineral-rich diets or supplementation if people persist with ultra-pure water.

A Simple TDS Blending Example

You do not need a laboratory to see how RO can push you too low and how remineralization or blending can bring you back.

Imagine your spring water measures 160 ppm TDS. A well-working RO membrane removes 95 percent of that, leaving you with about 8 ppm. That is firmly in the very low TDS zone.

If you then pass that 8 ppm RO water through a remineralization cartridge that adds back calcium, magnesium, and bicarbonate to raise TDS by roughly 100 ppm, you end up in the neighborhood of 108 ppm. That sits in the “excellent” band described by multiple sources: clean, mineral-balanced, and far from both extremes.

Some households with safe source water even blend a small amount of filtered but unsoftened spring water back into RO to raise TDS. For example, mixing one gallon of 10 ppm RO water with one gallon of 210 ppm filtered spring water yields around 110 ppm overall.

Several TDS guides, including Romegamart and Pure Aqua, explicitly mention blending and TDS controllers as practical tools to target the 150–300 ppm range.

The exact numbers will depend on your setup, but the principle is simple: treat RO as a reset, then consciously rebuild a mineral profile that matches how you want your water to taste and support your health.

Health Considerations: Reconciling Conflicting Views On Low TDS RO Water

It is natural to feel confused when one respected source says low TDS water is safe and another warns about long-term risks. The key is to understand what each is actually measuring and assuming.

The Water Quality Association’s paper on low TDS water focuses on direct evidence of harm from demineralized water itself and notes that global agencies do not have data showing such water causes disease. Their point is that hydration, temperature regulation, and nutrient transport do not require dissolved minerals in water.

By contrast, many of the cautionary articles about very low TDS water are looking at total mineral intake, digestive comfort, and subtle, long-term effects. Waltr highlights that very low TDS water can reduce magnesium and salt intake by around 20 percent, which may matter for people whose diets are not mineral-rich. Romegamart’s discussion of a WHO study interprets the findings as indicating that demineralized water might negatively impact calcium and magnesium intake over time, especially where diets are already borderline.

Paqos and Pure Aqua both emphasize that extremely low TDS water can be bland, may be slightly acidic, and could contribute to digestive discomfort or mineral deficiencies if it is your only water source and the rest of your diet does not compensate. They also note that infants and those with increased mineral needs may not be best served by very low TDS water.

My practical takeaway, based on this mix of evidence and field experience, is that RO-treated, very low TDS water is best handled in one of two ways. Either you clearly understand that your diet and possibly supplements cover your mineral needs, and you use ultra-pure water by choice for specific health or culinary reasons, or you take the simple step of remineralizing or blending your RO water to bring TDS back into a moderate, supportive range.

Practical Steps To Evaluate Your Low TDS Spring And Decide On RO

If you are standing in your kitchen with a TDS meter in one hand and RO brochures in the other, here is a practical way to proceed, framed as a flow of actions rather than a checklist.

Start by measuring your TDS with a basic meter. Dip the probe into a clean glass of your spring water, wait for the reading to stabilize, and note the number. If it sits roughly between 50 and 300 ppm, you are in the general zone that multiple sources consider good for taste and mineral balance. If it is above 500 ppm, RO starts to look more compelling for both taste and scaling reasons. If it is below about 50 ppm already, you are likely dealing with highly treated or naturally demineralized water where remineralization deserves attention, with or without RO.

Next, look beyond TDS. Request or review any available water quality reports for your spring. Focus on nitrates, arsenic, lead, and other heavy metals, as well as microbial indicators. Educational resources from libraries and municipal programs stress that TDS alone cannot tell you whether pesticides, herbicides, or microbes are present. If any of those contaminants are detected at concerning levels, a serious treatment setup—often including RO, carbon, and UV—moves from “nice to have” to “necessary.”

Then, consider your household. If you have infants, elderly family members, or people with chronic illnesses, err on the side of more robust treatment. At the same time, talk with your healthcare provider about dietary mineral intake if you plan to rely heavily on very low TDS water. Sources that caution about low TDS emphasize that diet can offset many hydration-related mineral concerns.

Finally, match your hardware to your goals. For a clean, moderate TDS spring, polishing filtration may be all you need. For a spring with low TDS but subtle chemical or microbial risks, RO plus remineralization is often ideal. If you badly dislike the taste of your current water, targeting a specific TDS band and mineral profile—such as the 70–120 ppm range that some bottled waters aim for, or the 200–300 ppm band favored by many mineral water enthusiasts—can turn hydration from a chore into something you genuinely enjoy.

Short FAQ

Does low TDS always mean my spring water is safe?

No. Low TDS simply means there are fewer dissolved solids overall. Educational materials from libraries and water-quality experts emphasize that harmful substances like pesticides, industrial chemicals, or microbes can be present even when TDS is low. You still need proper testing or treatment to be confident your water is safe.

If I install RO on low TDS spring water, what TDS should I aim for afterward?

Most science-backed and practical guides converge on a moderate TDS range. Values around 50–150 ppm are often described as excellent for everyday drinking, and 150–300 ppm is still very good for taste and mineral support. Instead of staying at near-zero after RO, consider remineralizing or blending until your treated water lands somewhere in that band.

Is very low TDS RO water bad for my health?

Technical reviews from groups like the Water Quality Association state that there is no solid evidence that low TDS water by itself causes disease. However, summaries of WHO research and analyses by Paqos, Romegamart, Waltr, and others point out that very low TDS water contributes few minerals and may be less comfortable for digestion, especially over the long term or in vulnerable groups. The safest and most enjoyable approach is usually to remove contaminants with RO, then restore a sensible level of minerals and TDS.

Pure, safe water is not just about stripping everything out; it is about targeted treatment and thoughtful balance. If your spring water already has low TDS, an RO system can still be a smart upgrade in the right circumstances, especially when paired with remineralization. When you understand both the strengths and the limits of TDS and RO, you can design a home hydration setup that respects your spring’s natural character while delivering the kind of reliable, health-conscious water your household deserves.

References

- https://wqa.org/resources/consumption-of-low-tds-water/

- https://www.lapl.org/neisci/kits/water-quality/why

- https://houstonwatersolutions.net/importance-of-maintaining-low-tds-levels-in-your-water/

- https://www.aavawater.com/blog/the-tds-of-your-drinking-water-is-important-for-health?srsltid=AfmBOop5h2frH7w8aU_iRGyPYRTQjt1ONNjDnKnZzHYAfthl1EzbLqCz

- https://chansonqualitywater.com/blog/ideal-tds-for-drinking-water-health-and-taste-guide?srsltid=AfmBOopxM89lxmUqyKg_thgUWciQc97mPUpRMcpzoa6BlB0HRPdGZF8B

- https://cleanairpurewater.com/dispelling-the-spring-water-myth/

- https://ionexchangeglobal.com/water-tds-level/

- https://miamialkalinewater.com/why-is-low-tds-in-the-water-important/

- https://www.ontakewater.com/importance-of-tds-in-safe-drinking-water/

- https://www.waltr.in/blog/if-the-tds-are-low-does-that-mean-the-water-is-safe

Share:

Effective Pre-Treatment Solutions for Oil-Contaminated Water RO Systems

Effective Solutions for Low Water Pressure Areas Under 0.2 MPa